For many people in Lagos’ LGBTQ+ community, living authentically is not a given but rather a risk you have to take. The underground Ballroom scene offers an escape from relentless discrimination, creating a safe space for Queer people to exist fully, fostering hope and creativity. Photojournalist Temiloluwa Johnson captures the joy and resistance born from this thriving underground culture in her award-winning project, “Heavenly Bodies.” Here, Johnson talks to writer Gem Fletcher about love, chosen families and her photographic legacy.

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around. Each year, we meet a selection of the winners and hear, in their own words, what went into capturing every monumental shot, from beautiful scenery to watershed historical moments.

Photojournalist Temiloluwa Johnson’s award-winning photo, “Mother Moves, House Approves,” almost never happened. The night she documented her first Ballroom at Lagos Pride, there was a heavy storm, which caused terrible gridlock on the roads. She was caught in the rain, which exacerbated her asthma, and she sat in traffic for hours, cold, shaking, sneezing, finally arriving at the event two hours late and completely drenched. Once she stepped into the venue and felt the pulse of the beat, she forgot all about the journey.

“I opened the door and found so much positive energy,” the Ibadan-based photographer recalls. “The exhaustion and sickness I was feeling immediately disappeared, and I was in complete awe. I just kept saying to myself, ‘This is a good day to be Queer.’” At the time, Johnson had no idea that documenting the event would change her life personally and professionally, affirming her identity and landing her a World Press Photo award just twelve months into her career.

I was in complete awe. I just kept saying to myself, ‘This is a good day to be Queer.’ Events like Pride and the Balls are a resistance. We are saying we are here and will continue to celebrate our existence.

Until the 1990s, Ballroom was a lesser-known African-American and Latino LGBTQ+ subculture with roots as far back as the mid-19th century in the United States. Ballroom is not simply a party; it’s an entire world built by Queer people for Queer people. The events are a haven, a place to be together and fight erasure in a world where many are still denied personal freedoms. During the Balls, attendees compete in houses (chosen families) for trophies, prizes and perhaps the most potent reward—prestige. Although Ballroom has entered mainstream consciousness thanks to pop culture like “Paris is Burning,” “Pose” and “My House,” it remains a vital underground scene in cities like Lagos.

Johnson, who is 24 and came out last year, explains the importance of Queer spaces to counterbalance the oppressive turmoil many LGBTQ+ people face every day in Nigeria. “Being Queer is political,” she says. “Events like Pride and the Balls are a resistance. We are saying we are here and will continue to celebrate our existence. The Ballroom provides safety and anonymity, allowing people to express themselves freely without fear of persecution, disturbance or imitation. It’s a refuge, a way to connect with our chosen families and space to exist on our own terms in the world.”

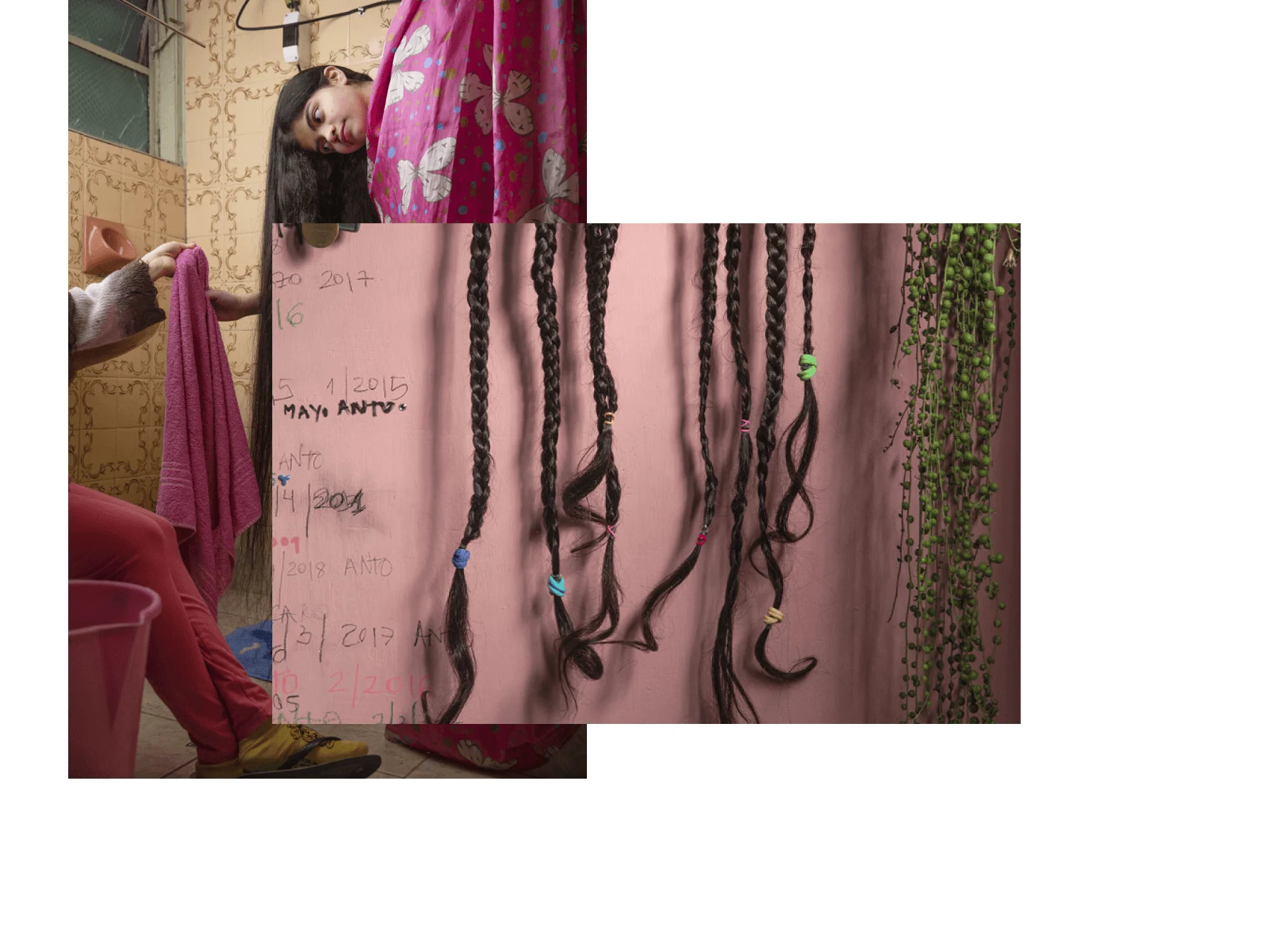

On the shoot, Johnson’s goal was simple: be fluid and follow the vibe. She took pictures for eight hours, moving between the main event and backstage, capturing performers as they competed in a range of categories, including Hair Affairs, Luscious Lips, Sex Siren, European Runway, Realness, Dip & Spin and Mother of the Year. Unlike other events where inconsistent lighting and navigating wild crowds slow photographers down, Johnson’s biggest challenge was doing work that captured the energy of the Ballroom while retaining her collaborators’ anonymity.

“It was tough,” explains Johnson about the project’s limitations. “The threat of violence against Queer people in Lagos is very real. You have to be careful not to be at the right place at the wrong time. The events always occur in undisclosed locations to protect the community’s safety, but still, many people are too scared to attend. Foregrounding privacy forced me to relate to the subject in new ways, through movement, their bodies and the diversity of expression, and I found it compelling.”

Johnson’s award-winning image from “Heavenly Bodies” depicts the Mother of the Year and her adoring house children in a shared moment of elevation. “To me, it’s a reminder that family isn’t always about blood, but about those who see you, protect you and lift you up,” says Johnson. This ethos also mirrors the photojournalist’s engaged and accountable approach to image-making, which she describes as less about documentation and more about “immersing, confronting and preserving” through storytelling.

The project’s title was inspired by the Ball’s 2024 theme, “Heavenly bodies: notes on Fola Francis,” in memory of the Queer icon who tragically passed away in December 2023. Francis—an actress, model, entrepreneur, activist, Mother of the House of Ivy and one of the country’s most visible Trans women—passionately fought for the liberation of trans and non-binary people in Nigeria, using her platform to advocate for the community while creating spaces like the Lagos Ballroom scene for people to be affirmed in their identity. “She was the mother,” says Johnson, who had previously collaborated with Francis. “She was kind, charming and radical. Most importantly, she had such deep love for the community.”

Love reverberates through Johnson’s project. You can feel it in the commitment of the performers, the audience’s desire and, perhaps most importantly, through the photographer’s gaze. Johnson’s ambition is that the project and its sentiment validate the community and create a living archive for Nigeria’s Queer community. “As much as the work is about love and celebration, it’s also about legacy,” says Johnson as we end our conversation. “Moments like this deserve to be seen and remembered, because they tell stories of joy and survival against all odds. ‘Heavenly Bodies’ reaffirms why I do this work. I don’t just want to capture images, but honor the people in them.”