America’s meat packing industry, much of it focused in the country’s Midwest, employs an unusually large proportion of immigrants, refugees, and non-citizens. It’s an industry known for grueling hours and difficult conditions, and one that was hit particularly hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Economic Policy Institute in 2020 claimed that meat and poultry workers were, when it came to COVID-19, the most impacted and least protected group of workers in the United States.

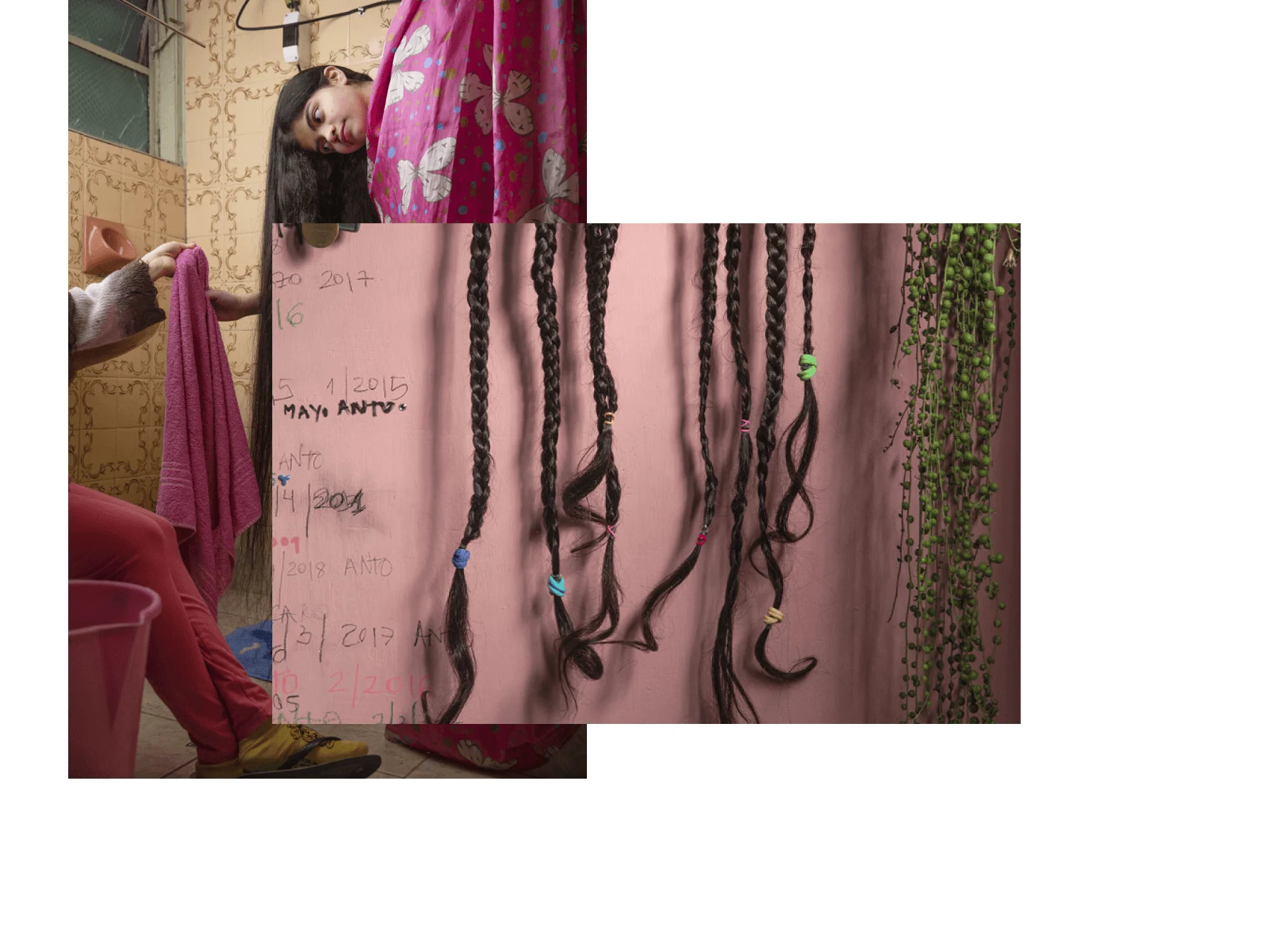

An immigrant to the US himself, photographer and filmmaker Ismail Ferdous started his current project – “The People Who Feed the United States” – in 2020, creating portraits of immigrants employed in the Midwest’s meat industry, making visible a largely unseen and often exploited population that powers America’s food industry.

All Images Copyright Ismail Ferdous / Agence VU'

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around, in the photographers’ own words. See the whole series here.

The opinions expressed in this first-person interview are those of the photographer and do not necessarily reflect those of WeTransfer.

“Early on in the pandemic, I was ill with COVID-19 and researching projects. I’ve worked on immigration stories before, one of which was on the new generation of South Asians coming to America, a class of successful immigrants embodying the ‘New American Dream.’ But, of course, many immigrants don’t find that dream.

I was thinking about how I could tell the stories that aren’t being told by American photographers or magazines. I’m an immigrant in the United States myself, though I’d rather call myself an expat as a way of challenging the idea that only white people can be expats. I don’t think I came to America with an ‘American Dream.’ I was curious about this country as a photographer and visual storyteller more than anything else. I want to tell stories by looking at America with a different pair of eyes.

I became interested in finding stories related to COVID-19, but the story I found is not a COVID-19 story; the pandemic just made it worse. I started the project in the summer of 2020, and I’ve since taken photographs in South Dakota and Nebraska. In South Dakota, I worked close to a meat processing plant in the Midwest. Americans call these parts of the nation ‘Flyover States,’ as in, no one actually wants to visit them. You don’t see many stories coming out of these places, but I’m interested in the unknown or the less popular parts of the country.

These pictures are of people who work in the meat processing industry. Finding the protagonists wasn’t easy—these people often work 12 to 14-hour shifts, sometimes seven days a week, and can start very early. I ended up using sources like nonprofits, labor unions, and activists to get in touch with them.

The consumption in the United States is limitless. American supermarkets offer unbelievable options and variety, but all of that comes at the cost of overproduction. How do you keep the prices low? Well, you can’t know the answer until you see behind the scenes of these industries. Specifically, who’s doing the work… A lot of it’s done by immigrants and refugees who fled war or conflicts in their own countries. Many speak no English, so their only option is the manual labor of meat processing. In one factory there might be 60 different languages spoken. Using people who are here ‘pursuing an American Dream’ is a big advantage for the corporations, and for some of these people that dream turns into a nightmare.

A lot of those I met had developed physical injuries or disabilities from the work, particularly from repetitive physical tasks. Say you cut the livers out of pigs, that’s your job. Imagine doing that over and over and over for maybe 15 hours a day. Some of the workers told me their shifts are so busy they don’t even get a chance to go to the bathroom. This is all stuff I heard from the workers I spoke with.

COVID-19 made all of that worse. For some of those who got sick, the 14-day leave period granted wasn’t enough; many of these workers are old and the lingering effects of COVID-19 presented serious problems. Many quit, but lots of these immigrant workers didn’t know they could file for unemployment claims, or didn’t know how to.

When it comes to meat, people worry about animal rights, but they often forget who cuts all this meat, packs it up, and sends it to market. I bet if you asked people in the United States who makes their food they wouldn’t know that it’s immigrants. I bet they never even questioned it. I made this project as a way of giving faces to the people behind these industries, as a way of making their voices heard. I think portraiture is often underestimated. You look at a portrait and you feel intimacy, like these people could be your neighbors, cousins, friends. Portraits have the power of engagement.

Giving the protagonists dignity and showing them not as victims but as people is really important to me. There’s the very classic photojournalistic way of photographing migrants: often just showing suffering or a miserable way of life. The story I’m telling here is not a happy one, but I’m completely against this tendency to depict these people in very sad ways. How would they like to be seen? These people should be represented with dignity and respect.

My ‘Rana Plaza’ project questioned supply chains, how the West consumes things made in the East. With this project, it is all happening within the West, but it is those same marginalized people—people of color, immigrants, and refugees— that are doing the work.”