When the Covid-19 crisis reached Latin America, it had a catastrophic impact on the education system. Statistics suggest that in this region, students lost more class time than children elsewhere in the world. Remote learning experiences depended on households' access to technology and the internet, leaving children from low-income families most impacted. In her series, “The Promise,” photographer Irina Werning collaborated with 12-year-old student Antonella Bordon, who offered up her most precious treasure—her hair—in exchange for getting her life at school back.

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around, in the photographers’ own words. See the whole series here.

The opinions expressed in this first-person interview are those of the photographer and do not necessarily reflect those of WeTransfer.

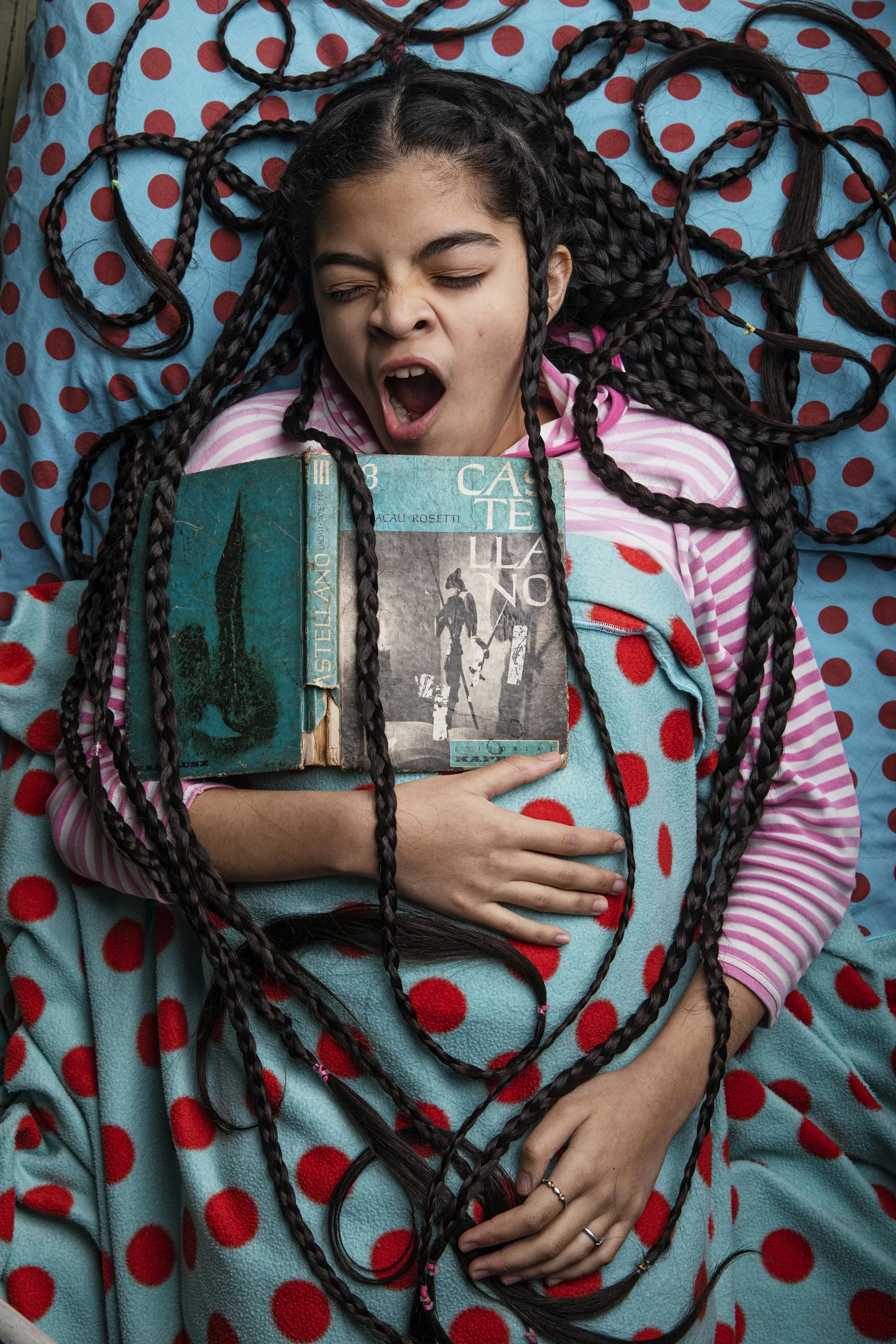

“Six months into the pandemic, Antonella Bordon looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘Hurry up with your hair ideas. Last night, I promised to cut my hair when school opens again.’ Like many young women in South America, Antonella's hair is a vital part of her identity. It’s a connection to her ancestry, and she's very proud of it. Indigenous communities believe that hair is sacred and that it’s an extension of our ideas. It should never be cut unless something tragic happens. For Antonella, cutting her hair was an offering to the universe, her most precious treasure in exchange for her school life back. It was an attempt to call forth a supernatural force that might fulfill her elusive wish.

I first became captivated by the relationship between hair and indigenous roots in 2006 after photographing three girls with long hair in the Andes. I began searching for young women all over the country. I would always ask the girls about the significance of their long hair—and the response was always personal—‘My mother looks after it,’ they'd say, or ‘My Grandmother tells me not to cut it.’ Maintaining long hair is also an important intergenerational bonding ritual, often undertaken by the mother or grandmother. No one speaks of this, but it's an important cultural aspect of Latin American life.

I first met Antonella in 2018. She lives on the outskirts of Buenos Aires in a small house in the port suburb of Dock Sud with her parents and older sister. She's a shy character and often uses her hair as a shield. We stayed in touch, and when the lockdown happened, I started visiting her once a week. Like all kids, she was very depressed and bored, so taking pictures and celebrating her hair became a release. Sometimes I'd be a fly on the wall documenting her life, and other times we would explore more playful ideas. It was fun for her, and we became very close.

When Antonella made the decision to cut her hair, our entire collaboration changed, and a new project, “The Promise,” was born. While hair was still the protagonist, the focus shifted to the education crises in Latin America and how emotionally devastating it was. Antonella's promise was testament to the extraordinary value kids place on a normal school experience. For me, it was a chance to tell a deeper story about inequality in my region and a broken bridge of education that left many feeling isolated.

As the pandemic progressed, I watched Antonella as she’d daydream of friends, blackboards and backpacks. School is a massive part of her life—it's where children's lives happen. Being away from her friends was terrible, and the pain and loss were palpable. The lockdown in Argentina was very strict, you could only leave the house to go to the supermarket or pharmacy, so Antonella rarely left her 322 sq ft house. She was anxious and scared. Even at 12, she was worried about the pandemic’s effects on her family's health, income, education and friendships. ‘I know that distance doesn’t matter in friendships,’ Antonella would say, ‘but who's gonna explain that to my heart?’

Even before the pandemic, education was a problem in Latin America, plagued by deep structural inequalities that mirrored the vast income inequality in the region. Around 10.5 million young students experienced disruptions to their education. Learning experiences were dependent on households' access to technology, internet access, and the availability and ability of parents to provide at-home schooling, leaving children from low-income families most impacted. The future for students in Latin America is under threat. Ignoring this tragedy could lead to intractable crises with no quick, easy solutions.

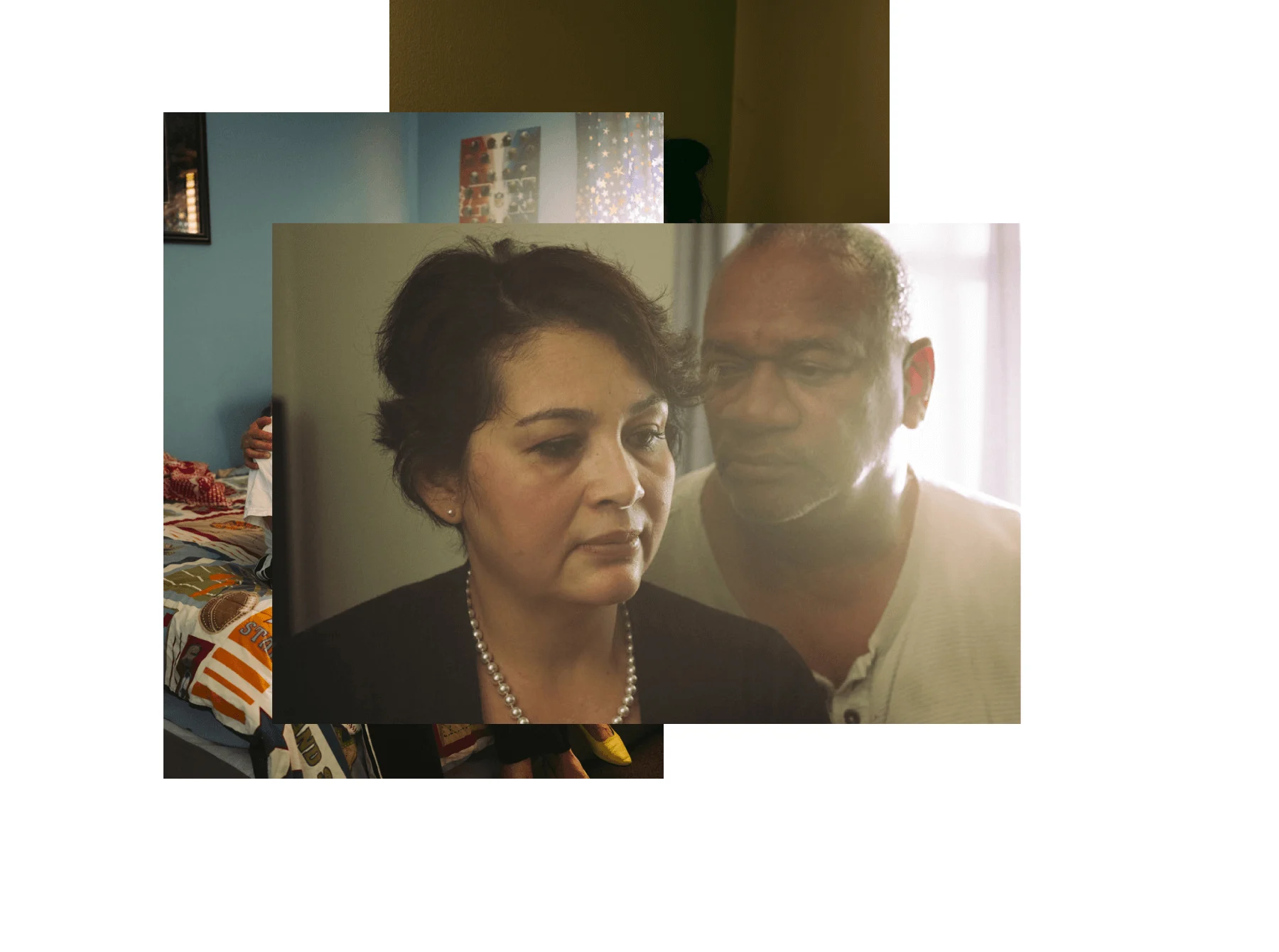

Education is a priority in the Bordon house. Antonella's parents emigrated from Paraguay to ensure a better life for their daughters. Her mother's phone was available to her every day for remote schooling, and she ensured Antonella never missed a class. In many ways, Antonella is an exception in her generation. Most children don't receive this level of support from the family. It's important to mention that life wasn't easy at that time for her parents. Both lost their informal jobs, so they opened a shop from scratch in their house to make money.

The schools finally reopened in September 2021, and Antonella cut her hair the weekend before she returned to class. Surrounded by her family, her mother and I cried while we all took turns to cut her hair. I feel like I witnessed her grow up and start a new life, and she didn't look back. She's happily back at school, beginning teenage life, and her hair is currently being made into a wig for a child undergoing cancer treatment.

‘I always thought if I cut my hair, something would be missing, but when school disappeared because of the lockdown, that's exactly how I felt,’ Antonella says. ‘The truth is I wasn't sad when I cut it — I was happy. I've become a different person.’