Over the course of six months, photographer Kiana Hayeri and researcher Melissa Cornet created a portrait of the lives of Afghan women under the strict regime of the Taliban. In a country facing one of the most severe women’s rights crises in the world, “No Woman’s Land” captures their struggles, but also shines a light on the subtle yet powerful ways they are resisting—from secret classrooms to moments of quiet togetherness at home. Here, Hayeri tells Phoebe West how the pair approached the project despite the limited access under the Taliban regime, and why resistance is a necessity for the women of Afghanistan.

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around. Each year, we meet a selection of the winners and hear, in their own words, what went into capturing every monumental shot, from beautiful scenery to watershed historical moments.

Hayeri and Cornet are creating a photobook around “No Woman’s Land” - you can support their journey here.

Over six months, Kiana Hayeri and Melissa Cornet spent 10 weeks across seven provinces, speaking to 100 women and girls about what it means to be a woman in Afghanistan today. “We wanted to cover everything,” Hayeri tells me from Damascus. “We wanted to show what it means to be a woman in rural areas, in urban areas, for educated women, and uneducated, to show what has changed for them, and to look at all sides of the story.” The story of Afghanistan’s history is a long and complex one, full of political instability and a mercurial hold over women’s rights—“every regime has used women as a symbol,” says Hayeri, “either of modernity, or moral purity.”

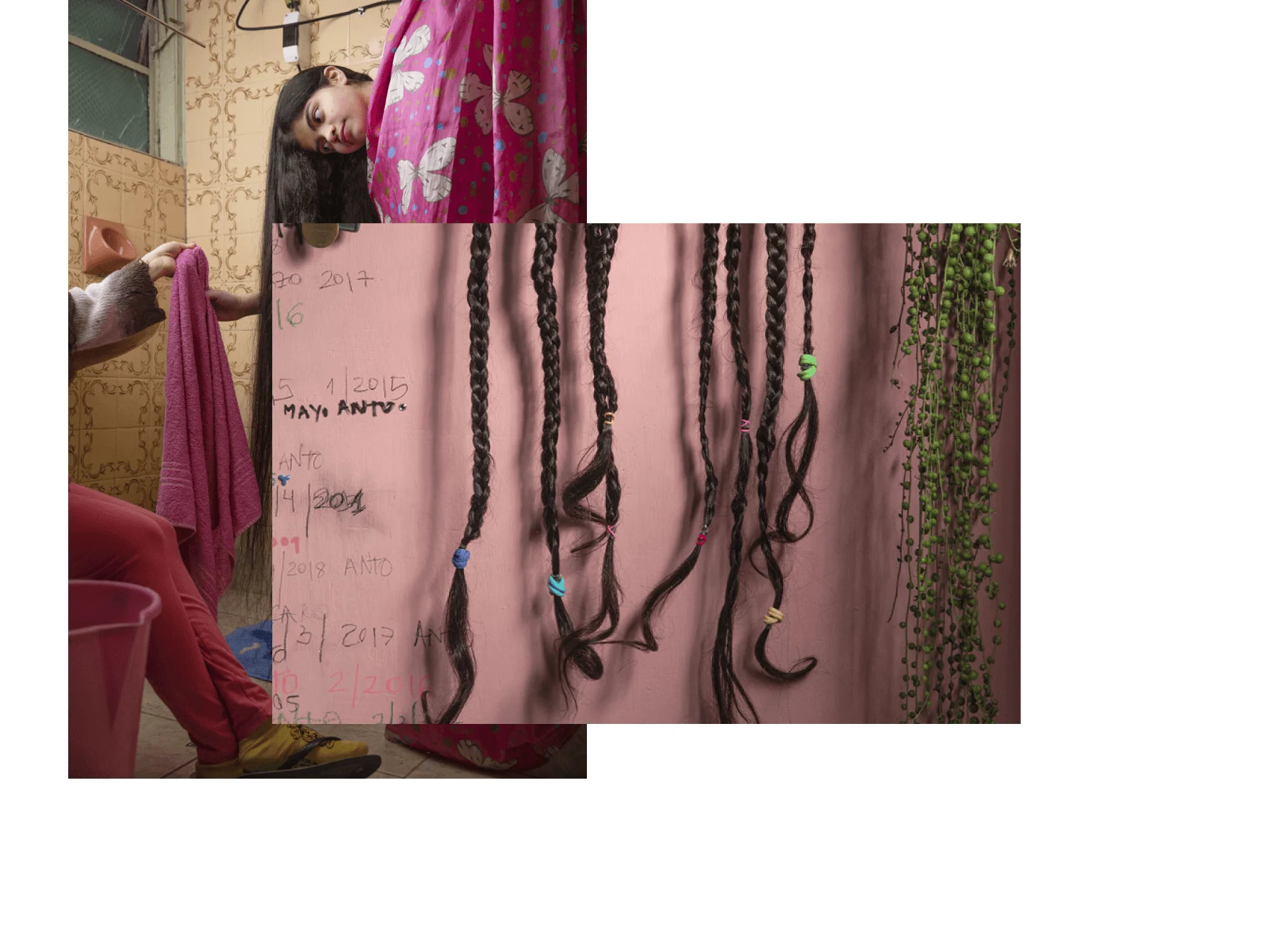

“I wanted to be very respectful,” Hayeri says. Every image was approached as singular, and created in partnership with the subject, ensuring their safety and agency. “Even if women were not comfortable showing their faces,” Hayeri explains, “they still have individuality in the photos.”

“No Woman’s Land” does not shy away from the darkness that pervades women’s existence in Afghanistan today, but it’s not the whole story either. Joy and hope exist, too, transcending the personal, to embody resistance and defiance within a land of oppression. “I hope it goes on to live as a documentation of what’s happening in Afghanistan,” says Hayeri, “and becomes something that the next generation will build upon—the foundation on which to build resilience and hope. They can look back at this and know what’s possible.”

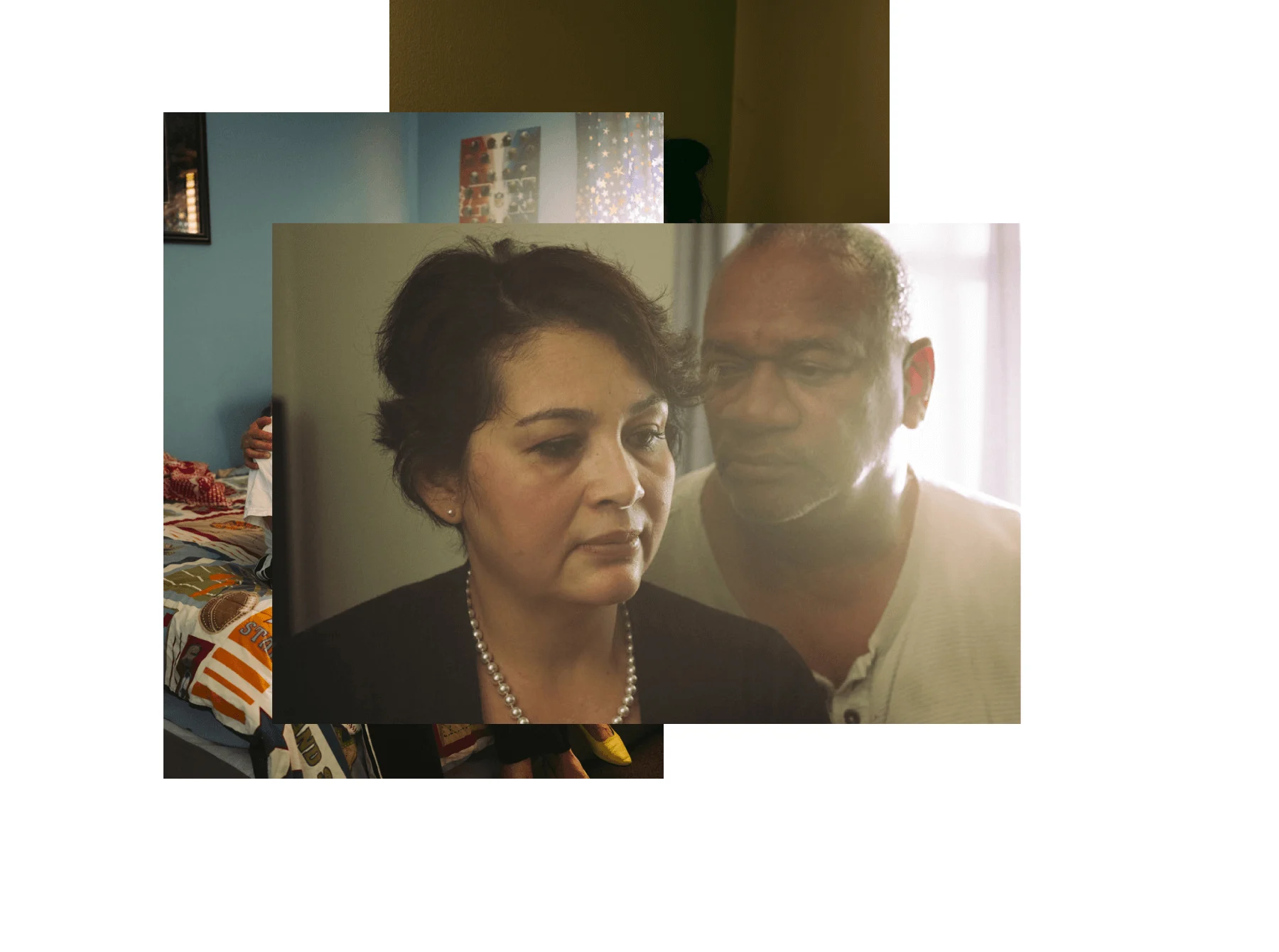

The project is a collaboration between Hayeri and women’s rights researcher Melissa Cornet. The process of working together was clearly revelatory for them both, allowing for creative scope and shared responsibility when it came to decisions surrounding the work. Beyond Hayeri and Cornet, the collaborative roots of the work extend much further. Given how limited access has become in Afghanistan under the Taliban, the space granted to them was thanks to the existence of networks already in place and a reputation within the community: “a lot of the access worked through word of mouth,” Hayeri explains, “so we would tell our network who we were looking to meet with and they would vouch for us.”

Both Hayeri and Cornet lived in Kabul for years, and hold a deep love for Afghanistan, which shines through in the work. They had a scaffold of trusted relationships on which to build, language to communicate without the need for a translator and time to ensure everyone taking part really wanted to be there: “Some of the scenes that you see, they’ve known me for three, four years,” she says, “so they know I wouldn’t do anything to risk their safety—and we had the luxury of time to go back again and again. This doesn’t happen in our field of work anymore.”

Hayeri has made a lot of work in Afghanistan, but this project felt unlike anything before it— “because I was on this grant, I could do whatever I wanted creatively and it was very fulfilling,” she explains. Hayeri says she’s always shot with natural light: “Afghanistan has this warm hue.” But for “No Woman’s Land” she decided to shoot using neon lights. “Afghans love neon lights,” she says, smiling, “you go to ice cream shops, restaurants, anything outdoors—they have neon lights everywhere.” As they felt the space afforded to women shrink further and further, Hayeri and Cornet decided to “bring the neon lights into their homes and into their spaces.” The decision to bring luminosity into the sanctuaries of these women makes it hard not to think about their skies turning from technicolor to overcast pallor as decades-long progress unraveled within weeks when the Taliban returned to power in the late summer of 2021.

Resilience is really not a choice. For women, and Afghans generally I would say, it’s a necessity.

Pasts and futures feel present throughout the work. Various shots within “No Woman’s Land” capture different generations of women—each frame holding multiple cycles of repression and political instability. It is difficult to fathom the expanse of what is newly gone and newly impossible for these girls—for the elders it is history repeating, an echo of a past life, but for the youth—their daughters and granddaughters—it’s fresh, whole futures rubbed out in an instant.

“Resilience is really not a choice,” says Hayeri. “For women, and Afghans generally I would say, it’s a necessity.” It is a great privilege to be able to think of resilience as a choice. Existing within the oppression that has, once again, become the reality for women in Afghanistan, resistance and rebellion exist on a molecular level—it is not taking place on the streets for others to watch, it is happening all the time: dancing behind closed doors, making art and creating henna designs become defiant acts of personhood in the face of erasure.

Making this work would not be possible now—any semblance of access that existed then has been shut down—but the scope of what was created is unbounded. “It’s very easy for people to put the title of gender apartheid on Afghanistan,” reflects Hayeri, “but they don’t talk about the apartheid that is happening in the West Bank. The fight for women’s rights goes beyond just Afghanistan. It goes to Palestine. It goes to America. It goes to Kenya!” After our conversation, Hayeri is joining the celebrations in Damascus for the 14th anniversary of the Syrian revolution, where military helicopters will drop flowers and confetti—a reminder that proximate to the fragility of women’s rights around the world lies the potential for change, and the possibility for something better.