For generations, New Zealand’s Ngāi Tūhoe have faced a battle with the state for themselves, and their homes, to be recognized. After moving to New Zealand in 2008, photojournalist Tatsiana Chypsanava began to reflect on the struggle of the Tūhoe people, their mistreatment by the authorities and their representation in the media, and in 2014, set out to tell a different story. She tells Bruno Bayley about her 10-year photographic journey with Tūhoe families, capturing everyday life, hope and community.

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around. Each year, we meet a selection of the winners and hear, in their own words, what went into capturing every monumental shot, from beautiful scenery to watershed historical moments.

Photojournalist Tatsiana Chypsanava moved to New Zealand with her young family in 2008. Soon after arriving, she learned about the Ngāi Tūhoe people of the Te Urewera region via a documentary exploring their past, their persecution and their dispossession of ancestral lands. The documentary went on to explore how, in the mid-20th century, Te Urewera was turned into a national park, “so that the land was taken from them yet again, alienating them, stopping them from being able to practice their cultural connection to the land,” she says.

Born and raised in Belarus with a father of Komi Indigenous heritage, and having lived and photographed on Indigenous land in Brazil, Chypsanava arrived in New Zealand aware of some of the complex challenges faced by Indigenous peoples. While working at The Archives of New Zealand, she became friends with members of a Tūhoe team preparing for a settlement hearing (a route through which Indigenous people can seek reparations for the atrocities carried out through colonization.) Her Tūhoe friends invited her to visit the village of Ruatoki, in Te Urewera, a trip that was to signal the start of an ongoing relationship with the people and the place.

The Tūhoe are, Chypsanava says, a people who “never lost their culture or language, who took part in the broader Māori Renaissance, contributing to the revitalization of Māori culture, the assertion of iIndigenous rights and the ongoing process of reconciliation and cultural recognition in New Zealand society.”

There were no images out there portraying modern daily life, it was all brutality. I wanted to create a counter-narrative to that.

While working at the archives, Chypsanava started to reflect on the Tūhoe people’s representation in the media. In 2007 the police carried out series of raids in Te Urewera under the Terrorism Suppression Act. The raids were highly controversial, mired in accusations of illegal surveillance, and—ultimately—although four people were charged for firearm possession, the Solicitor-General declined to prosecute a single one of those arrested for terrorism-related crimes. “300 police raided the village of Ruatoki... The images that came out in the media were all of armed police in balaclavas arresting people,” says Chypsanava. “The people were being portrayed as terrorists, the headlines in the press were horrible… Of course, there were no terrorists.” These events were still fresh in the community’s minds when Chypsanava started visiting Te Urewera.

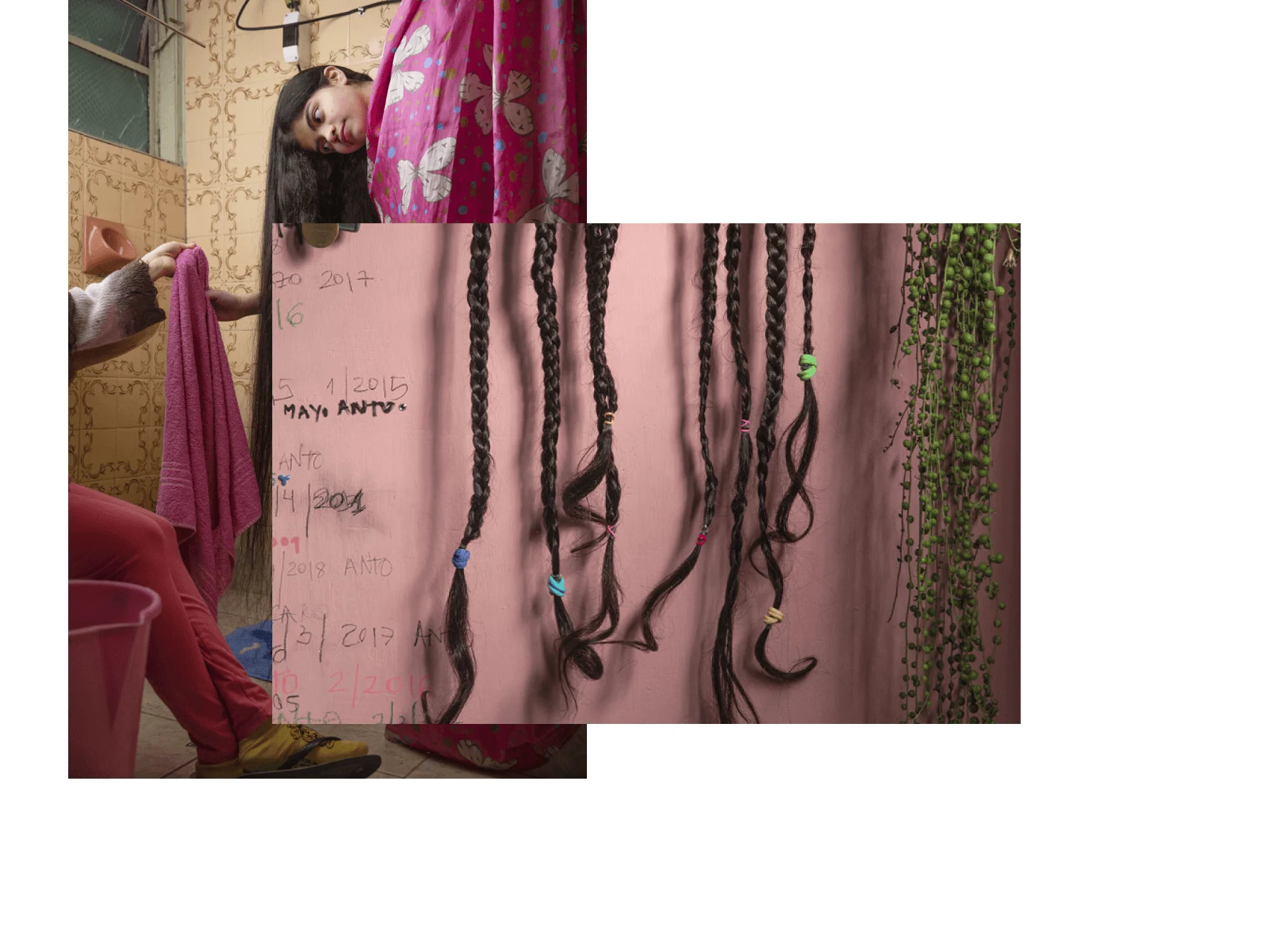

Then, in 2014, the Teepa family—who were to become prominent in Chypsanava’s work—were raided by the police. “That’s how this 10-year project started,” says Chypsanava. “The family home was raided by 30 police who had followed the wrong car and raided them in the early hours. They’re just elderly parents who raise their grandchildren and other young relatives as their own, plus some others, about 27 children in all. The police just said, ‘Wrong car, wrong house,’ and left without apology.” Chypsanava got in touch and was invited to photograph the family. “I’ve been going there since that happened. There were no images out there portraying modern daily life, it was all brutality. I wanted to create a counter-narrative to that.”

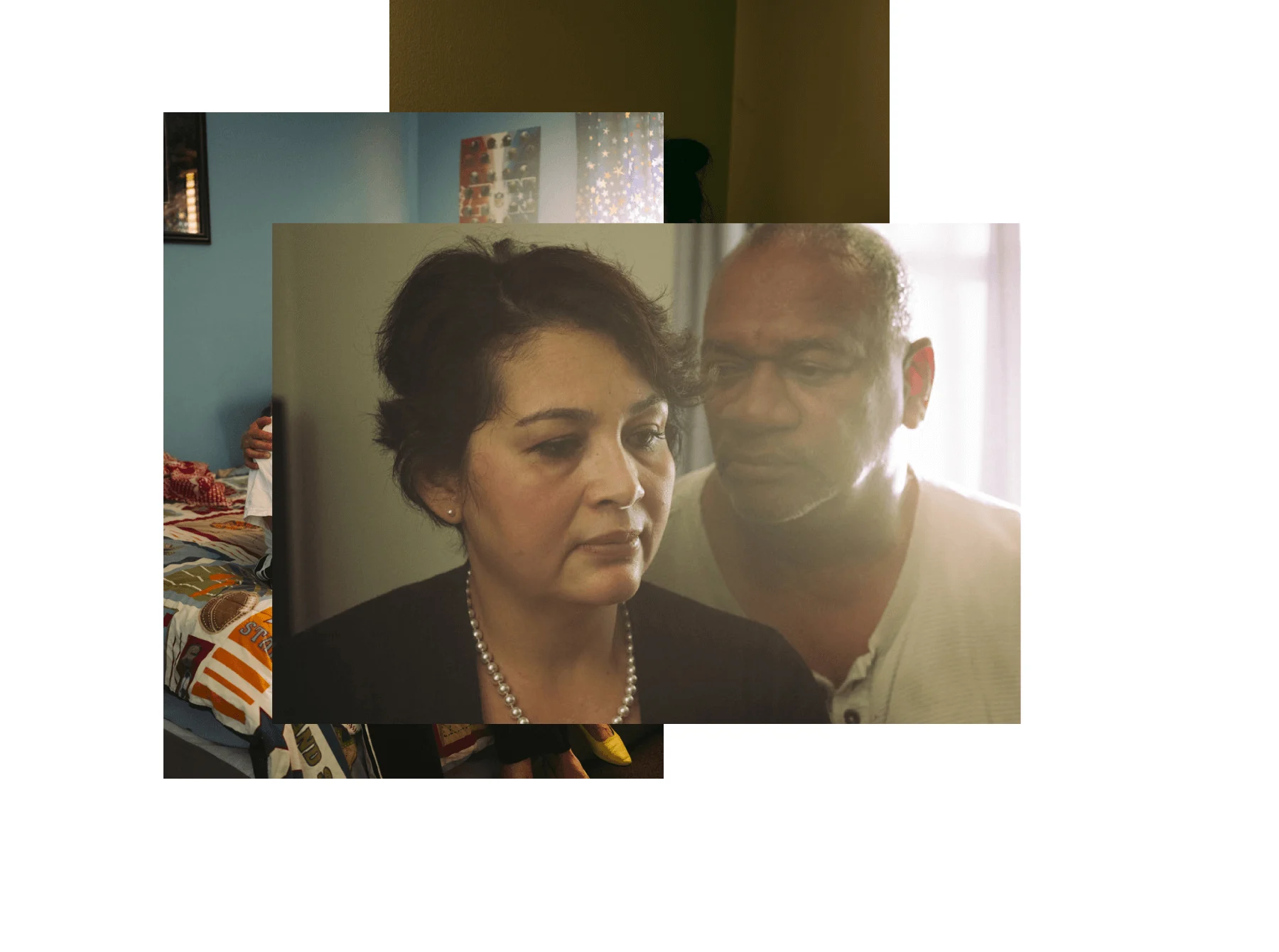

Chypsanava started documenting life in Te Urewera as she knew it: the kindness and openness of the community, as well as the challenging realities of life in the remote, mountainous region. She collaborated with Dr Pounamu Jade Aikman, a Maori anthropologist who, in 2016 and 2017, interviewed Tūhoe families impacted by police raids. “I photographed the people he interviewed; we were on the same page,” she says. “We were both creating counter-narratives.”

The 1954 creation of the Te Urewera National Park is, for Chypsanava, emblematic of the disconnect around the understanding of the region and its people in New Zealand: “For the public Te Urewera is an empty place. They want to feel about it the same way as they do about any other national park, without acknowledging it’s someone’s home.” Chypsanava wants her work to remind people that Te Urewera is not empty, that it is a home.

In a landmark 2014 ruling, the Te Urewera National Park was disestablished and the land was given legal personhood, a world first. “For the Tūhoe, Te Urewera is an ancestor,” says Chypsanava. “They trace their geneaology to Te Urewera itself, their ancestral lineage beginning with the union of Hine-pūkohu-rangi (personified as the Mist Maiden) and Te Maunga (the Mountain)... This lineage not only explains their origins but also emphasizes their profound connection to their land. For the Tūhoe the most important thing is their reconnection with Te Urewera, which involves more than just physical presence. It encompasses the care and wellbeing of the land using mātauranga (traditional knowledge) developed over centuries.”

Chypsanava describes a renaissance in traditional practices and renewed efforts to work the land in Te Urewera, to make it economically viable while also preserving and protecting its ecology. But for the Tūhoe, employment opportunities are scarce. “They are creating some businesses, making award-winning honey and [running] dairy farms, but these don’t create many jobs… So young people are leaving.”

“Some conservationists still think of Te Urewera and its people as having to report to someone, but the Tūhoe think of it as whenua, or their place of origin and return, their homeland (the word also means placenta),” says Chypsanava, reflecting on the ongoing, Tūhoe-led conservation efforts in the region. “Te Urewera is integral to Tūhoe identity, culture, language and customs. It is where they hold mana (authority) by ahikāroa (long-burning fires of occupation), and where they are tangata whenua (people of the land) and kaitiaki (guardians).” For many Tūhoe, residing in their ancestral homeland became impossible during Te Urewera’s era as a national park. Now 10 years on, the journey to healing has only just begun. Chypsanava acknowledges the challenges the Tūhoe face, but—hardships aside—their story, for her, remains one of hope.