Inspired by the Sapeurs—the people of the flamboyantly fashionable subculture La Sape that originated in his homeland—painter Zemba Luzamba’s subjects are always dressed to impress. He tells Ugonnaora Owoh that this colorful, vibrant style is an invitation to the audience to look closer, and that beneath the surface there are deeper meanings to be uncovered—stories of hope and rebirth, about the lives of African migrants and the everyday Black experience.

Zemba Luzamba approaches his art slowly, and he wants his viewers to do the same when they analyze it. “Take a pause, look closely,” he says. “Because a lot can be lost otherwise.” Luzamba was born in 1973, a year after former president of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mobutu Sese Seko, launched one of Africa’s post-colonial cultural revolutions, issuing a decree to change how people dressed. Known as the “Authenticité” campaign, Mobutu banned western-style suits and neckties, denouncing them as relics of colonial subjugation, and introduced the abacost—a tailored, collarless jacket worn without a tie.

Take a pause, look closely. Because a lot can be lost otherwise.

Though Luzamba has no memory of this time, he remembers growing up to witness the activism of Papa Wemba, the legendary Congolese singer who pioneered genres like rumba and soukous. He was one of the earliest supporters of La Sape, the flamboyantly fashionable subculture that originated in the Congo, known for his designer blazers, crisp shirts, floppy hats and bold color palettes. Through him and other pioneers, the Sapeurs—a group of men and women who dress in extravagantly elegant western-style clothing—emerged as a popular movement against Mobutu’s decree. Papa Wemba was one of Luzamaba’s earliest inspirations. He began painting the Sapeurs in 1995 as a test run on paper, works he would sometimes sell. By 2003, he began to see them as serious subjects that were informing his practice as an artist from DRC and by 2008, he was fully convinced that this was the path made for him.

When I ask him why painting the Sapeurs was important, he offers nostalgic reasons. “I’ve been attached to the Sapeurs since I was a child in Congo,” he says. “We had a history of not having the blazers and ties on us up until 1992, so it’s something most people of our generation got into because we missed that style in the 70s and 80s. So, when those decisions were reversed by the regime back then, we were happy. You could just come home from school and put on a suit just to look smart, without even going anywhere. It’s memories like this that led me to painting La Sape.” In Luzamba’s works, you will find men in colorful suits convening, standing with hands in pockets or sitting or clutching a walking stick.

Born in Lubumbashi, Luzamba’s father was an ophthalmologist who he describes as strict. Growing up, he was a happy child who excelled at everything he found interest in—gymnastics, karate, dancing and especially art. His love for drawing was shaped through comic books, then commissioned portraits which he sold. From the very beginning, there were no plans for a career in art because his conservative parents were convinced it wasn’t lucrative. They later changed their minds after he got a huge commission from the French Institute to make comic works that would be featured on two of their journals in 1989, leading him to Zambia where he had the privilege to assist the Zambian artist David Chibwe, under whose mentorship he learnt the foundational skills of painting.

I’ve been attached to the Sapeurs since I was a child. It’s something most people of our generation got into.

Over the years, his painting has evolved in concept and narrative. His works have explored the war in Congo, environmental hazards, communal practice and brotherhood. His latest bodies of work were exhibited at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery in Tower Bridge, London in the Spring of 2025. The exhibition was titled “Angallia Kwa Karibu,” meaning “look close” in Swahili, and the included body of work critiqued the viewers of art. “Sometimes you find that, especially in some artworks, people just look at the beauty and the color compositions and they move on,” he says. “But in these new works, I want viewers to interact with the artworks and in order to do so, they have to look closely at the context and try to understand why I made each painting.”

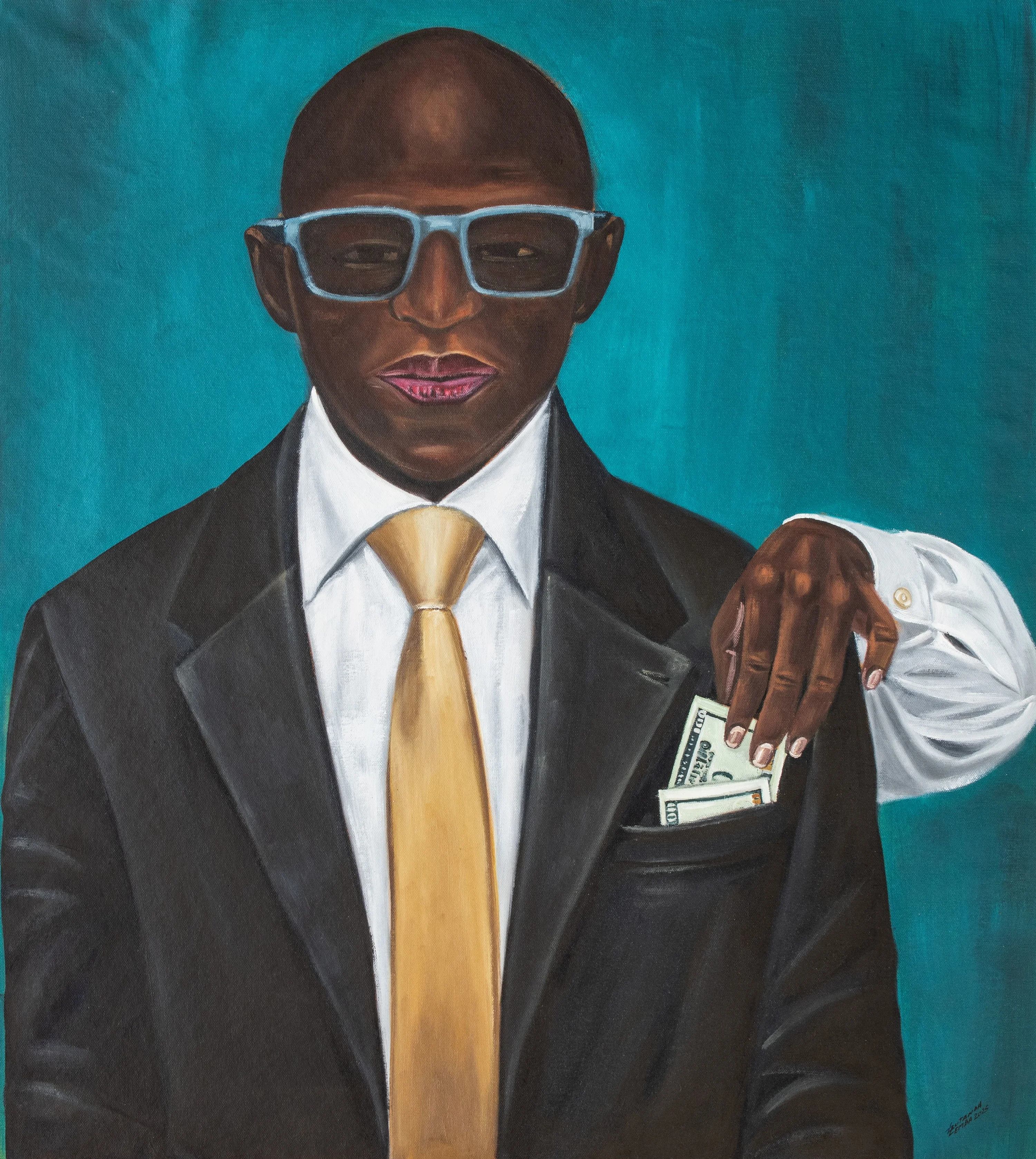

In “Black Tax 2,” a man stands elegantly clothed, while a hand reaches to pinch a dollar bill from his pocket. Here, Luzamba tries to depict the burden successful Black people face when they are expected to support family members as a way of paying back for the care and education they received in childhood. “Mkimbizi” (Asylum Seeker) depicts a man hurrying along the pavement with suitcases. A man Luzamba refers to as “a modern asylum seeker,” someone who has fled their home country not due to conflict or loss, but in order to dodge taxes and accumulate more wealth. In “Maisha Mapya” (new life)’ Luzamba explores hopes: a man gazes at an egg, a symbol of birth, while the cutting of a rope invokes the ceremonial practice of inauguration.

In all of these works, Luzamba passes no judgment, but rather hands the baton to the viewer, asking them to make what they want of each painting. “I want people to think beyond the Sapeurs in my work,” he says. “The Sapeurs are just a reflection of me because I identify as one myself. They just have to look deeper.”