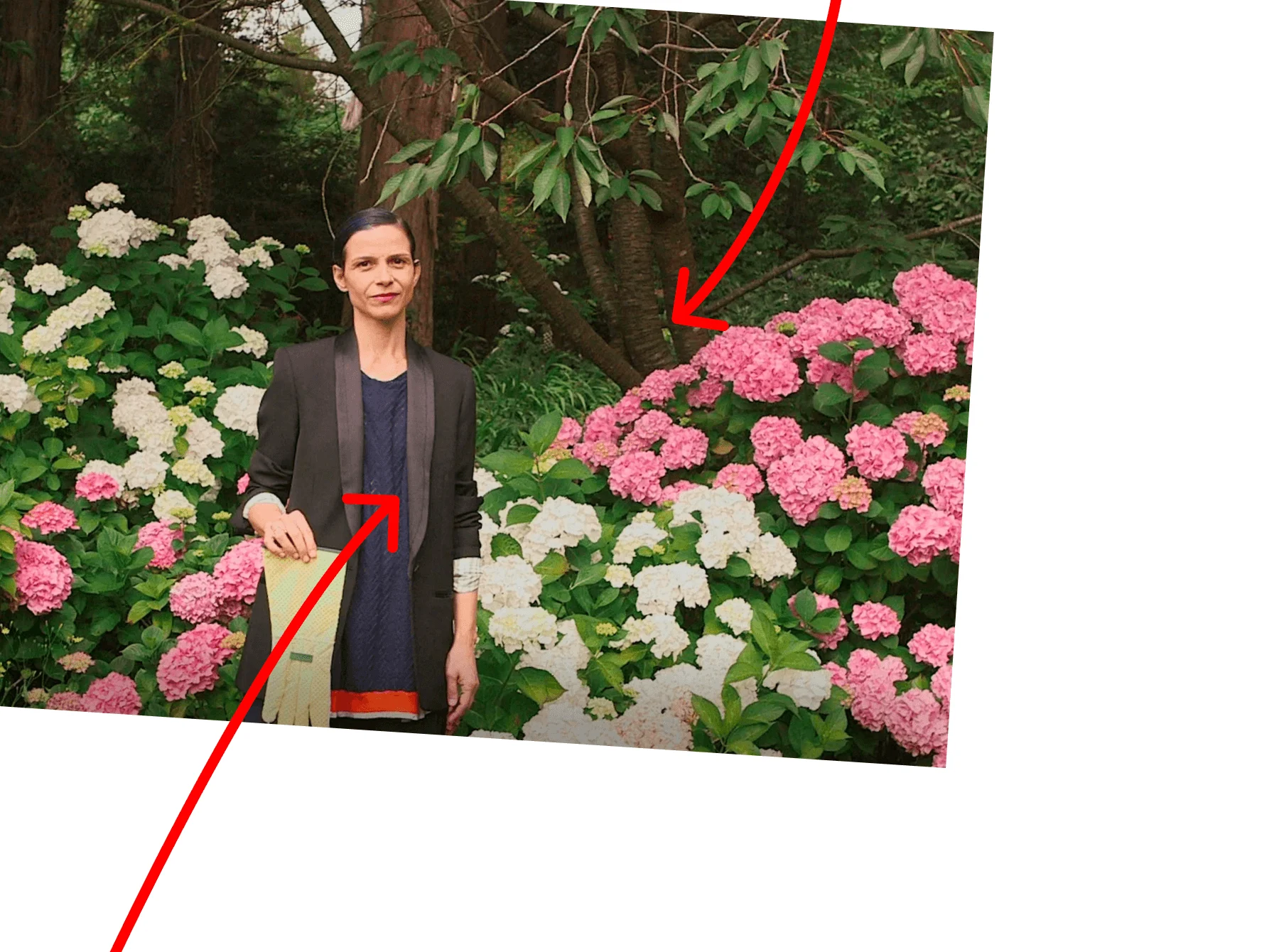

Pappas has an anthropological and phenomenological approach to his work, using a vast range of mediums — photography, language, video, and performance. Most of the time, his own body is the center of the work.

Berlin-based performance and visual artist Yiannis Pappas was born on the Greek island of Patmos, renowned for the UNESCO-listed monastery built there nearly one thousand years ago. So it’s perhaps unsurprising that his work is laced with an appreciation for ritual, beauty and discipline. Through his performances and the production of modern artifacts, which have been presented at the Venice Biennale, Yiannis peels back the layers of repression that shape the world around us and govern our lives. Allyssia Alleyne explains how Yiannis Pappas uses the self, the sacred and the silly to dissect the physical world.

He grew up surrounded by religion

Yiannis Pappas was born in 1978 in Patmos, a Greek island where he says religion “permeates the whole existence.” It’s best known as the site where the Bible’s apocalyptic Book of Revelation was written and, since 1088, the Monastery of Saint John the Theologian has dominated the landscape.

“My not into religion, but its presence in that environment is so strong. It was always tucked away in my mind, and a lot of my artworks are connected to religion,” he says. “I work a lot with the sacred, the holy and the mysterious to create a poetic but abstract language using opposing dynamics: figurative and abstract forms, soft and hard materials, and then, of course, the durational and the ephemeral...I like to approach that concept in a dark, humorous way. I don’t know if I always manage in the end, but that’s always my thinking.”

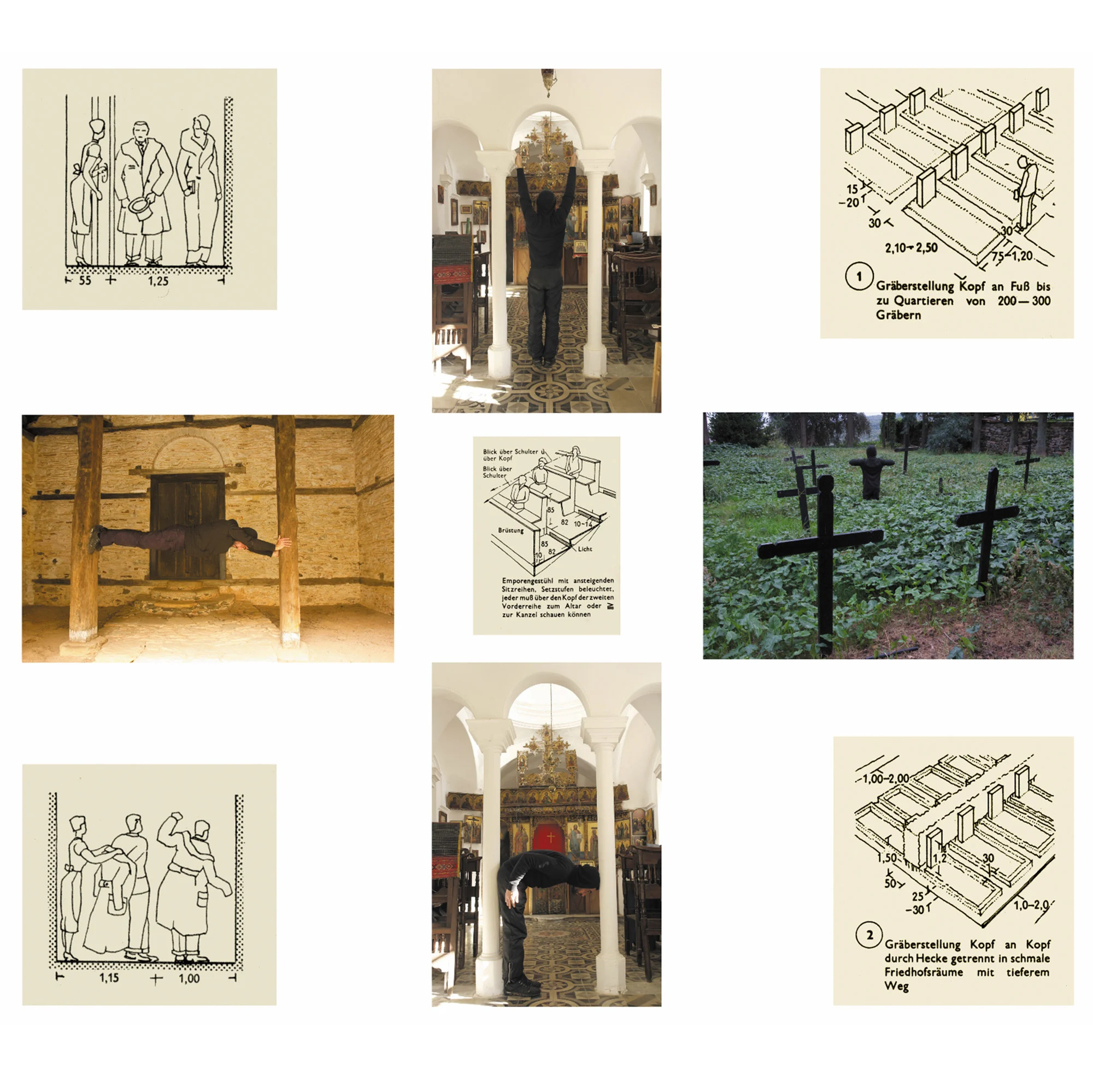

His most in-depth exploration of religion was connected to a 2013 trip he made to the Great Lavra Monastery, founded in 963 in the Mount Athos peninsula in Greece. For five weeks, he observed and interviewed residents, and participated in daily life to learn how the monks constructed and maintained their communities over centuries, while leading largely ascetic lives.

This experience was the basis of Spatial Ataraxia, his Master’s thesis at the Weissensee Academy of Art. The research inspired a number of works and exhibitions, including Askesis (2013), a video performance shot on the island, and a Control ’til End (2014), an installation of photos and drawings that opened at the Santa Maria Church in Bolzano, Italy.

He cut his teeth working with textiles, which remain a key part of his practice

While studying at the Athens School of Fine Arts, Yiannis made his living working in art conservancy at Greece’s Ministry of Culture and Sports. He specialized in the conservation of textiles, and found himself surrounded by ecclesiastical robes and folk costumes. “Working with textiles, while at the same time studying sculpture, I realized that they could be meaningful. It’s an everyday material we wear from the time we wake up to the time we go to sleep, but can also be about celebrating moments in our lives,” he says. “I thought that it could also connect well with my concepts.”

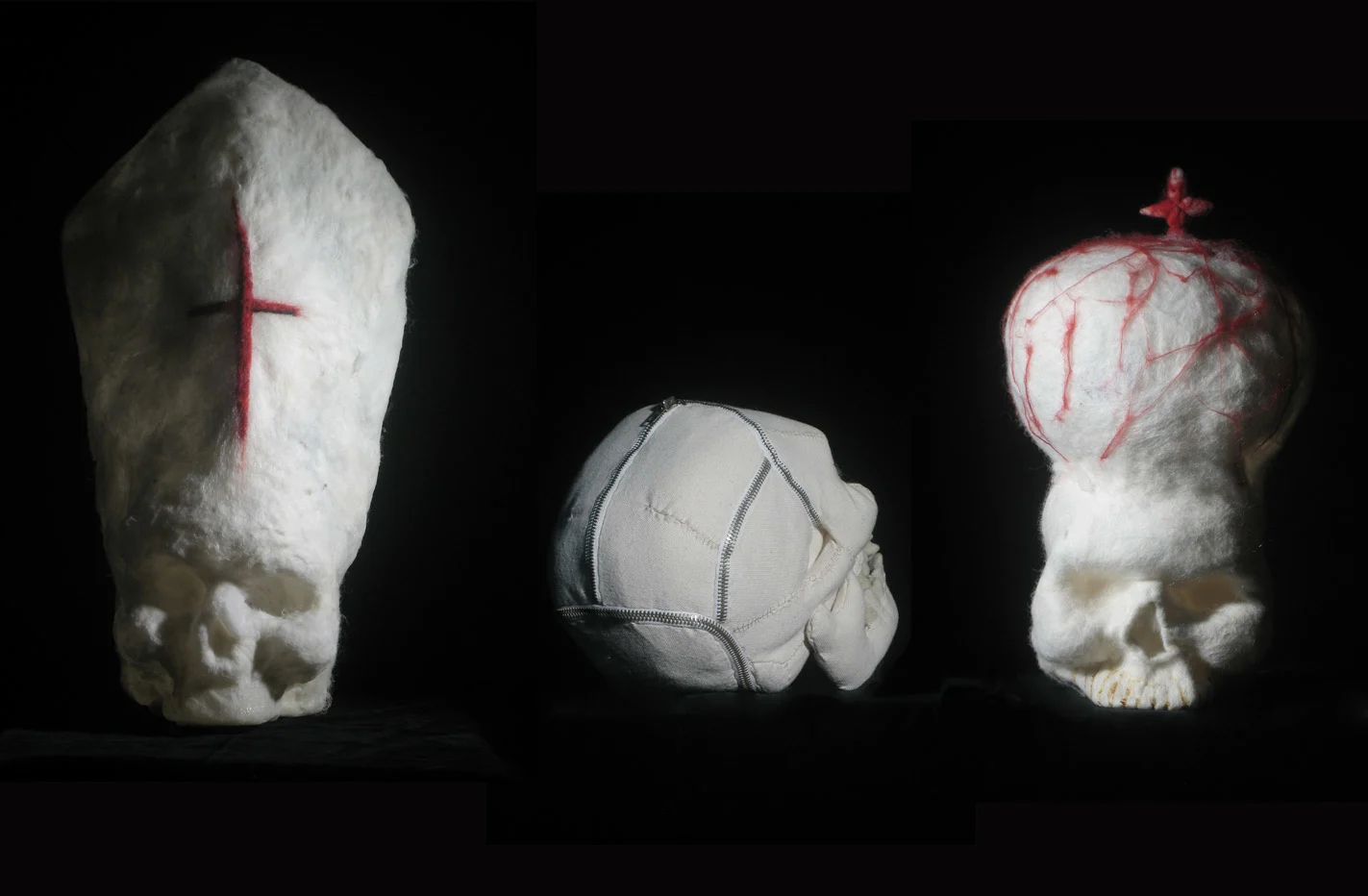

For Holy Vestments (2009), Yiannis created undergarments inspired by a Byzantine emperor’s robe he discovered during a trip to Mount Athos with the Ministry, including a robe made from gold-painted ping-pong balls. That same year, he fashioned skulls topped with religious, military and political headgear out of wool, zippers and other textiles for his sardonic Anatomy series.

His more technical skills came into play for Half-Staff (2017), a durational performance where he patched together a quilt from 80 countries’ flags, as well as a Semi-Glory (2016) for which he and the artist Nikolaos turned Athens’ Benaki Museum into a workshop and produced a massive white flag over the course of four days.

Oh, and the giant pair of briefs (Nation Panties) he waved in front of Checkpoint Charlie in 2011. Eagle-eyed observers would have noticed that the fly opening was positioned on the left side, rather than the right: an inversion mirroring the opposing button placements on men and women’s shirts. “The gendered masculinity is so obvious, so strong – soldiers, flags, poles,” Yiannis explains. “I wanted to criticize the politics of attention in a public space that’s also really closely connected to boundaries.”

Time is of the essence

Much of Yiannis’ practice centers on long durational performance. He says that interest was initially inspired by the work of Marina Abramović, one of his longtime supporters. “She was a catalyst,” he says. “ understanding of long durational performance as a totally autonomous medium: making it, performing it, seeing it and watching it. Somehow inspired me, and reset my point of view as an artist.”

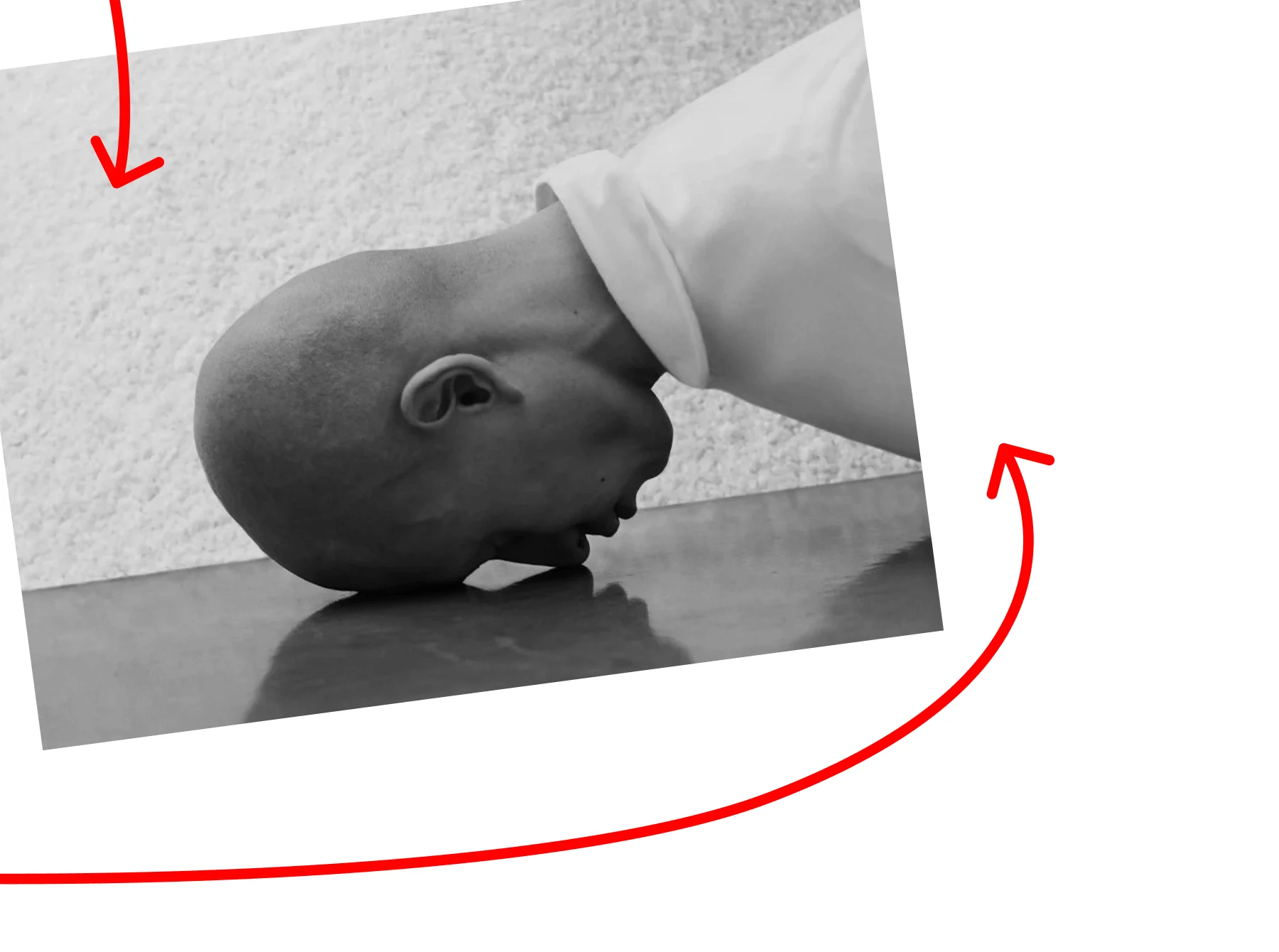

In his most recent performance, Grauzone, he sat unmoving in an armchair across from a television for 14 hours over the course of four days, his face connected to the screen by a textile sleeve that forced him to consider only the static playing in front of him. But that was nowhere near as grueling as one of his best-known works, Telephus. Part of a series of durational performances presented by the Marina Abramović Institute at the 2018 Bangkok Biennale, he spent 175 hours wrapping his body parts in plaster to create an imposing pile of casts, as a commentary on our “personal and collective asphyxia.”

He’s a serial collaborator

While many of his durational performances are solitary endeavors, Yiannis relishes the opportunity to collaborate with others, be that with organizations like the Marina Abramović Institute, or with fellow artists, including Thiago Bortolozzo, Alexandros Michail and Nikolaos. “It's a real joy to collaborate with people with whom you don't have to explain so much. They just understand you, and share a common language,” he says. “You develop respect and trust, and trusting your partner is a very element during a performance.”

He explores geo-politics and body politics

Many of Yiannis’ performances relate to borders and their enforcement. In Refugio, performed during the 2017 Buffer Fringe Festival, he and Alexandros Michail constructed and destroyed walls of red brick around themselves, seemingly at random. Staged in public squares on both sides of the demilitarized zone that bisects the country, dividing its Greek and Turkish populations, the performance drew attention to the arbitrary and fluid nature of the borders around us.

But Yiannis warns against taking things too literally. “ is mostly about the general repression that we experience…all these borders and territories we’re facing in our everyday lives.”

Take A Key (2016), for instance. For 34 hours, over the course of four days, Yiannis used a key to break through the walls of four successive cells. While he had Greece’s refugee crisis in mind when he conceived the work, he says that “at the same time, I wanted to leave it open so that people could what those enclosures meant in their private lives.”

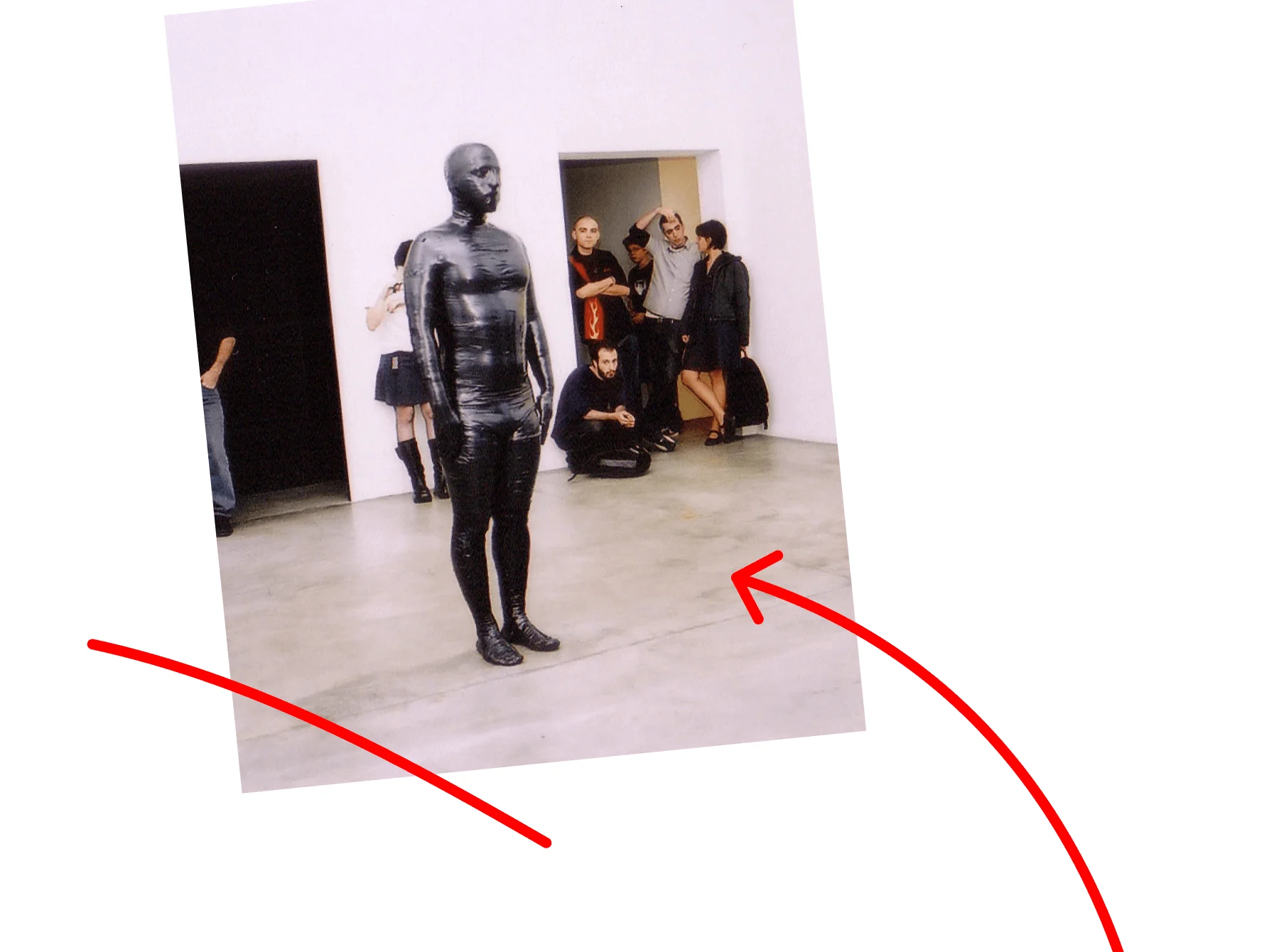

Yiannis is also interested in the ways that our own bodies are constrained and policed by external forces: the theme at the heart of Reflex, a durational work he debuted at the Volume Gallery in Berlin in 2017. Each time the work is performed, Yiannis empties out a bookshelf in the host gallery and steps into the space, offering up his undressed body to be ordered, catalogued and observed. This same message is communicated through The Archive, an ever-expanding installation featuring folders filled with his own hair, and framed capsules filled with his bodily fluids.

He’s scrutinizing the larger external forces that determine what treatment our bodily markers merit.

“I'm asking myself about how repressed we all are by our first border – that is, by our skin, our color, our gender,” he says. In the process, he’s scrutinizing the larger external forces that determine what treatment our bodily markers merit. “I believe in the notion that the body is a really powerful weapon . And for me, it's always directly correlated to socio-political genealogies.”