Terence Koh never ceases to surprise, using different media, including performative elements in his work. He is not compromising, but inclusive of the environment he is with.

For nearly a decade, Terence Koh was as close to a pop star as one could find in the art world: as likely to rub shoulders with Lady Gaga as Marina Abramović, while also making headlines with controversial pieces. But provocation turned out to be just one phase of the artist’s evolution, preceding a new focus on nature and connection. Allyssia Alleyne breaks down the artist’s personal and artistic evolution.

He first emerged as asianpunkboy

Terence Koh was born in 1977 in Beijing, China, and grew up in Mississauga, a suburb of Toronto. His mother, he says, often recounts a story about how he made and signed a drawing of an upside-down cat when he was three – the beginning of a lifelong love of drawing. But art wasn’t something he’d ever considered seriously as a profession.

“I was brought up by Chinese parents, so I still had that old-fashioned that I had to be either a lawyer or a doctor,” he says. “The idea of becoming an artist was like jumping off a cliff.”

One of his earliest creative endeavors was asianpunkboy, a rabbit hole of a proto-blog he started as a graphic design student at the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design in Vancouver. Online, he shared diary entries and photos taken by him and the skateboarding art students he was friends with, along with links to music, poetry, porn and whatever web 1.0 ephemera caught his eye.

Inspired by his friends’ zine-making efforts, Terence channeled asianpunkboy’s spirit of randomness and community collaboration into his own handmade zines, and asked them to contribute. “There were all these different people that I was exposed to, all these artists, and I was interested in fashion as well. And I thought, ‘Why don't I make it all come together in a physical magazine?’” he recalls. “I was just printing out things in a loft. People were coming over to drop off photographs and help us staple things...I don't think there were any themes. It was more organic.”

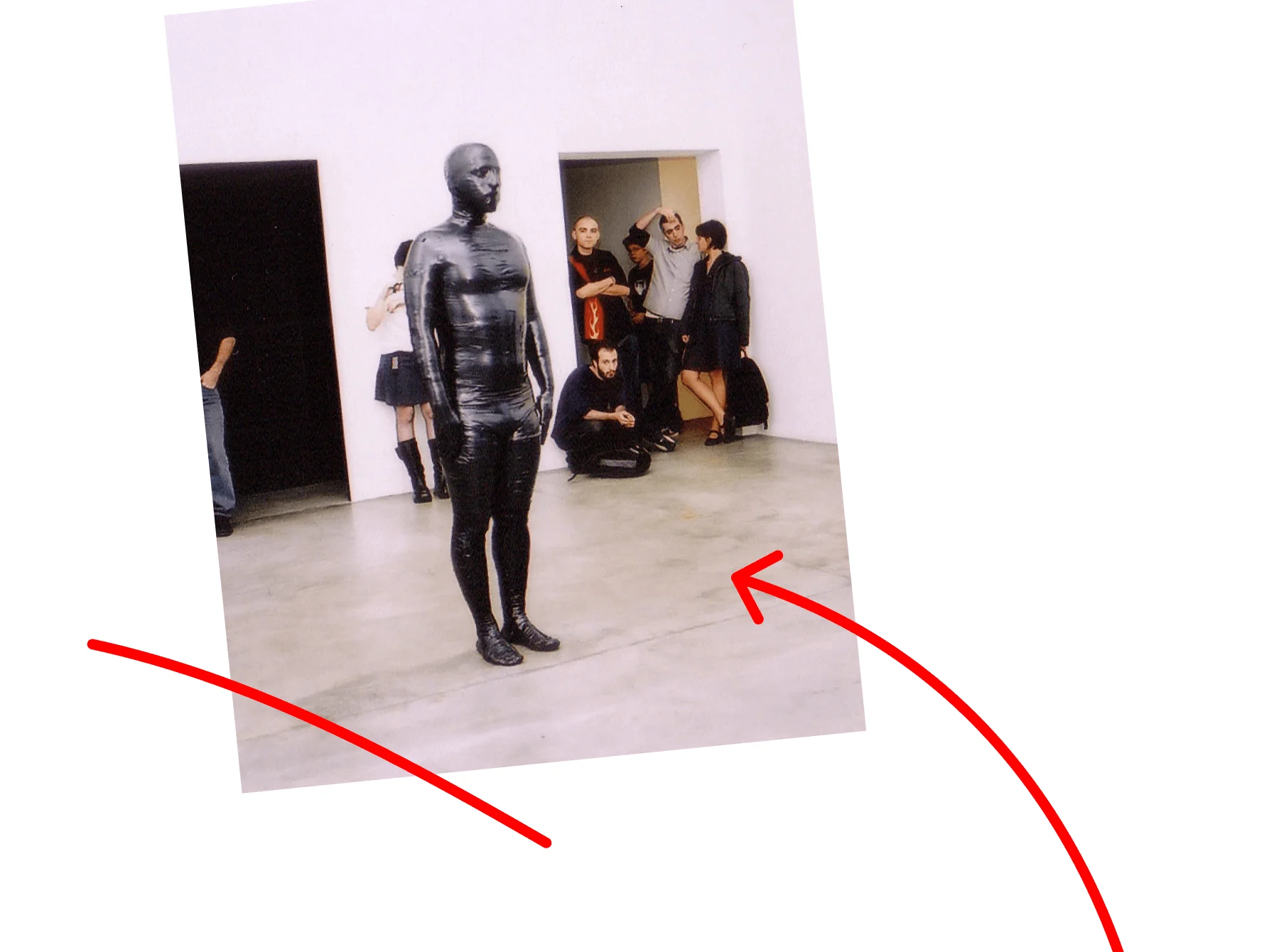

When he moved to New York shortly after graduating to intern at Visionaire magazine, asianpunkboy turned out to be his ticket into the art scene. Collector Javier Peres, one of the blog’s many luminary fans, gave Terence his first break in 2003 on the basis of it, inviting him to put on the inaugural exhibition at his new gallery, Peres Projects, in Los Angeles.

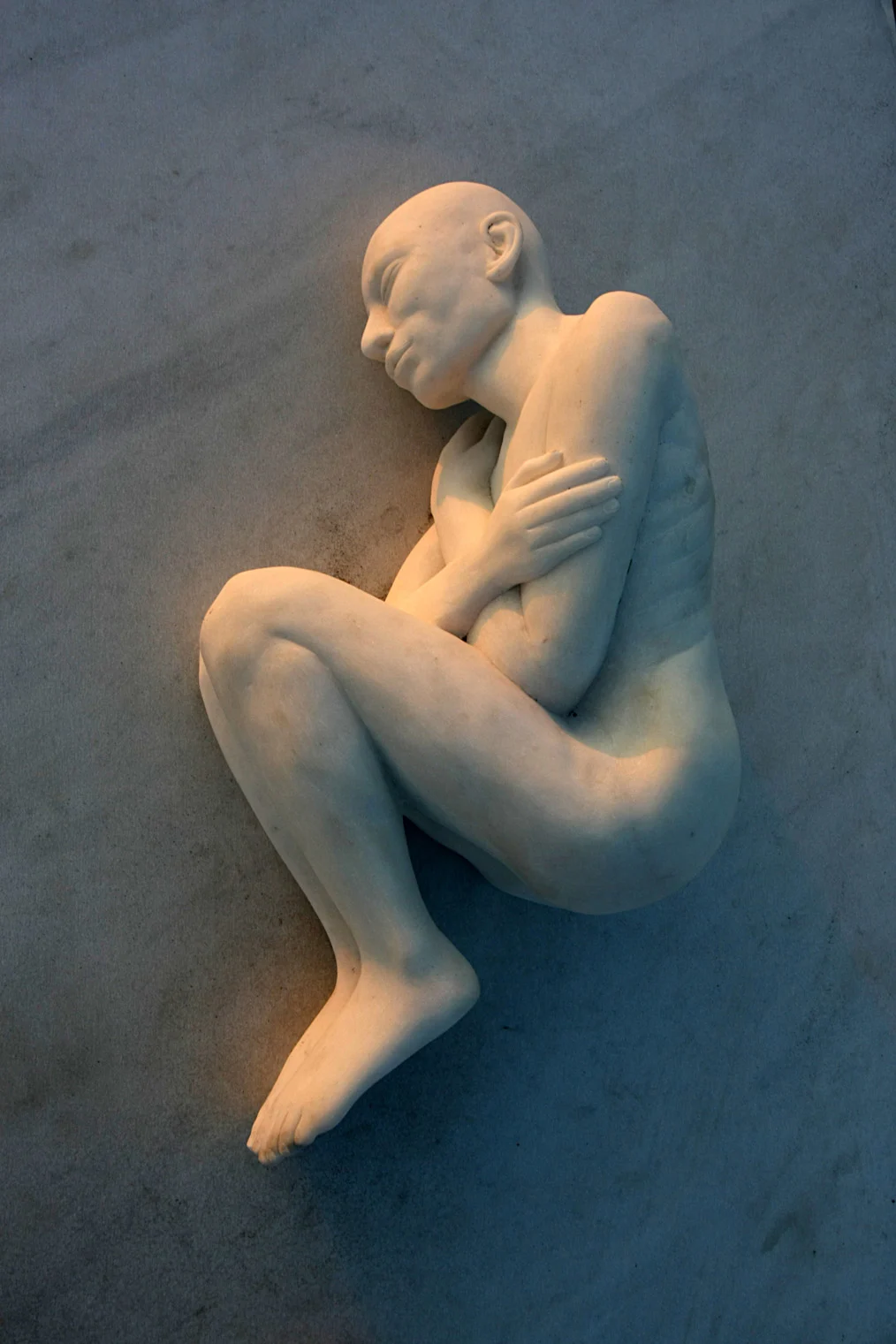

For this first outing, titled the whole family, Terence filled the gallery’s basement with white powder and two albino parakeets. The next year, a version of the work was presented at the Whitney Biennial, which officially put him onto the international art world’s radar.

He became a mid-aughts rebel

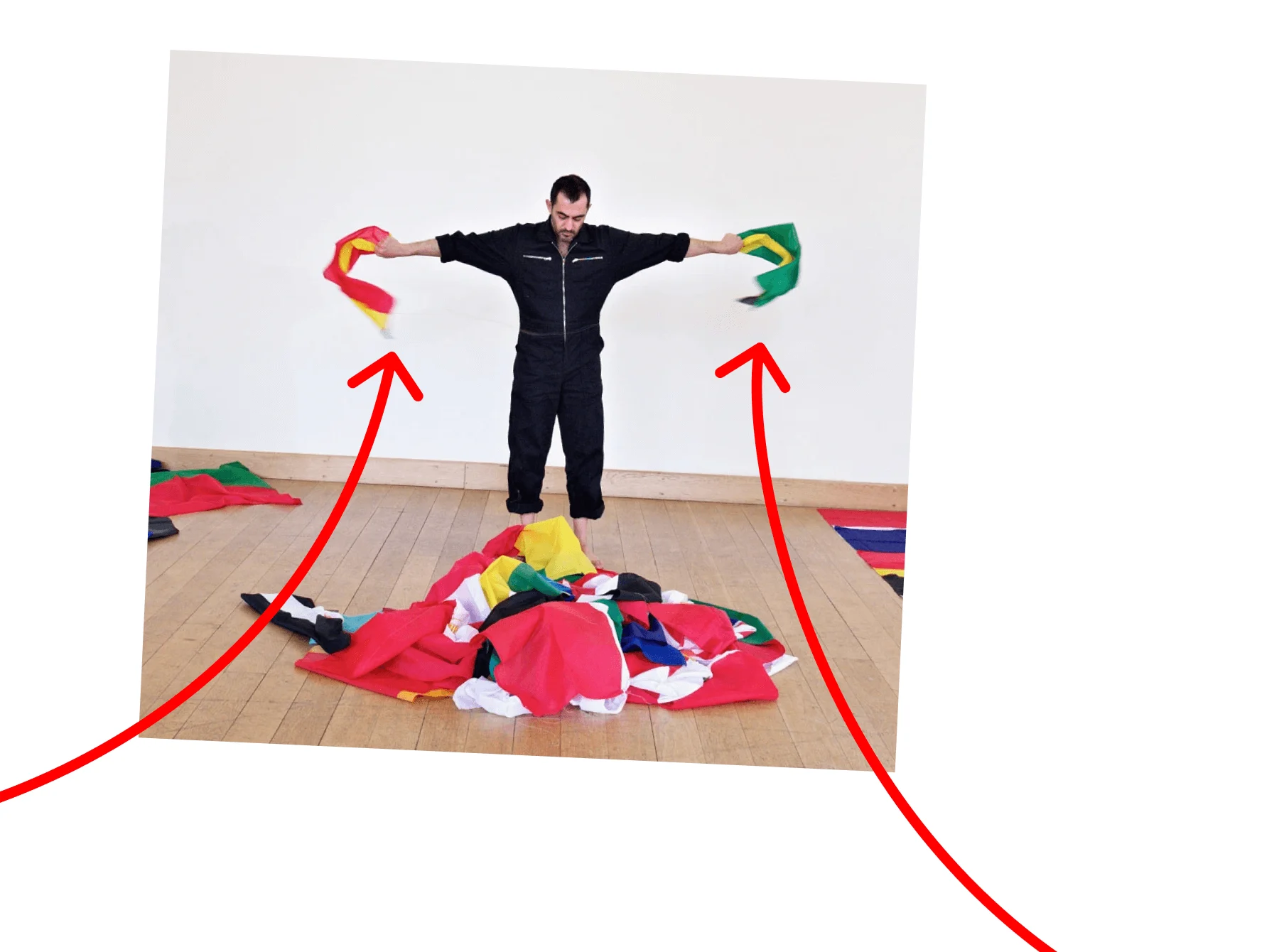

Early on, Terence developed a reputation for provocation and controversy, with paintings infused with semen, statues of Jesus and the Virgin Mary with oversized erections, and gold-plated chunks of excrement that sold for a purported $500,000 at Art Basel in 2007. He was a darling of the creative scene, garnering international press coverage as he flitted between the worlds of art, fashion and music in an ever-changing uniform of designer clothes.

“There were all these things converging in New York at the same time,” he remembers. “Fashion shows were also rock concerts, pop stars were on the cover of Vogue. Rock stars were hanging out with artists, and artists were hanging out with poets, and poets were hanging out with beggars, and beggars hanging out on Wall Street.”

Early on, he developed a reputation for provocation and controversy, with paintings infused with semen, statues of Jesus and the Virgin Mary with oversized erections

It was during this phase of his career that he was first introduced to Marina Abramović by MoMA curator Klaus Biesenbach. He later interviewed her for an episode of The Terence Koh Show, a one-time YouTube series where he interviewed other creatives. He’s still good friends with Marina today.

“Marina is so inspiring in so many ways,” he says. “There's an unexplainable connection that beyond just visuals and talking to each other, and it's not a superstitious, psychic thing. We somehow have a communication beyond language.”

In January 2010, he started a spate of collaborations with Lady Gaga, customizing the double-sided piano she played with Elton John during her first Grammys performance. Shortly after, he designed the pearl-encrusted ensemble she wore to a gala benefit for amfAR, inspired by his 2008 sculpture Boy by the Sea, as well as the mannequin-armed piano she played that evening. The two also performed together, first in a video performance, 88 Pearls, and later in GAGAKOH, a live concert at a Tokyo nightclub.

“Our connection and collaboration was like two children playing,” Terence recalls of their relationship. “ a sense of innocence.”

He went through a monochrome phase

For a period, Terence was known to appear at events dressed all in white. His studio was filled with white walls, white furniture, white tools, white books. White dominated many of his works, too. For Untitled, his 2006 show at Kunsthalle Zurich, he once again filled one room entirely with white powder and two white birds, while, in another, he installed some 1,200 glass display cases filled with white-painted objects picked up at various places: ceramics shops, sex stores, tourist booths and flea markets.

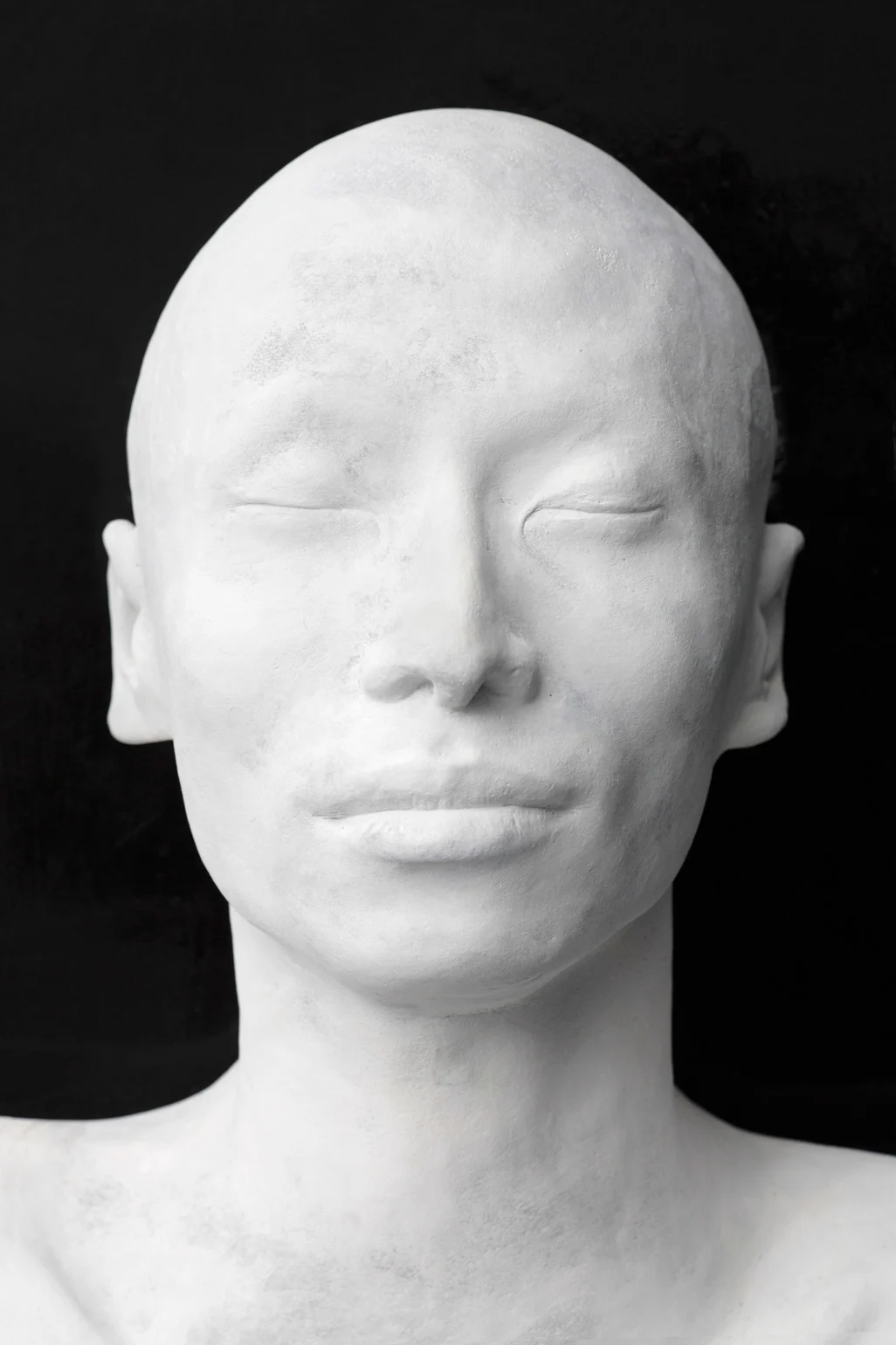

Similarly, for Crackhead, part of the 2006 exhibition USA Today: New American Art from the Saatchi Gallery at London’s Royal Academy of Arts, Terence placed 222 black plaster casts of heads in a towering wall of vitrines, among other monochrome sculptures of everyday items, including a chandelier, a drum kit and a urinal filled with religious figurines.

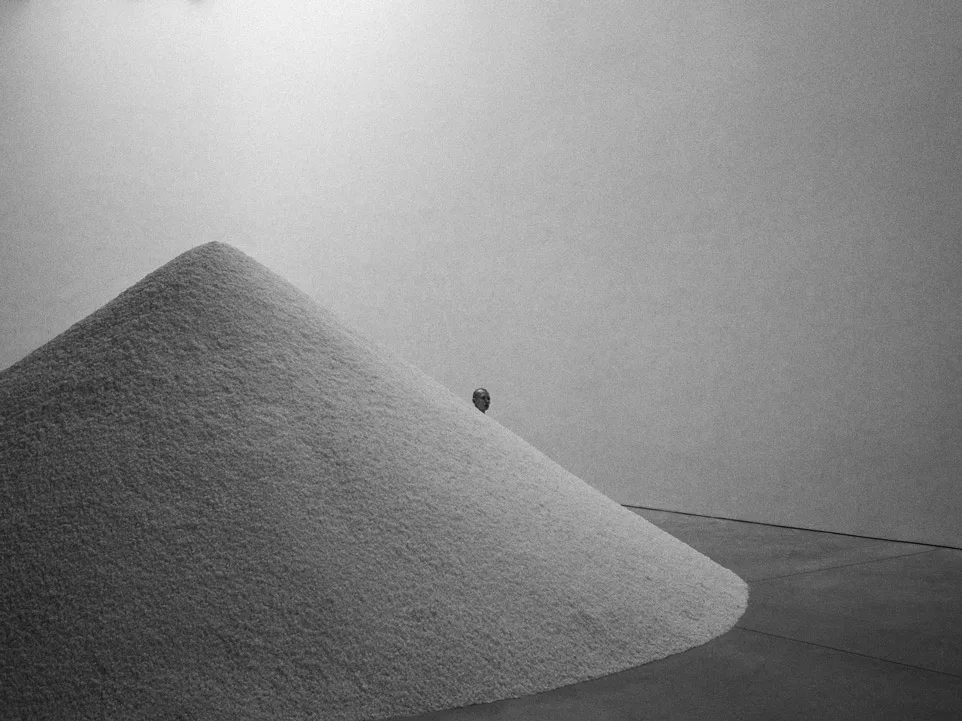

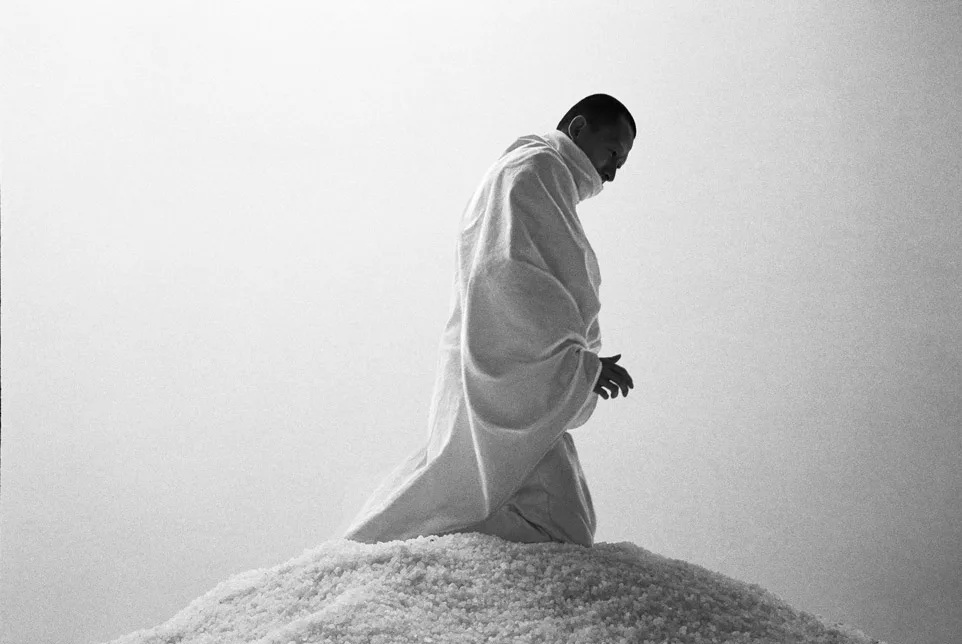

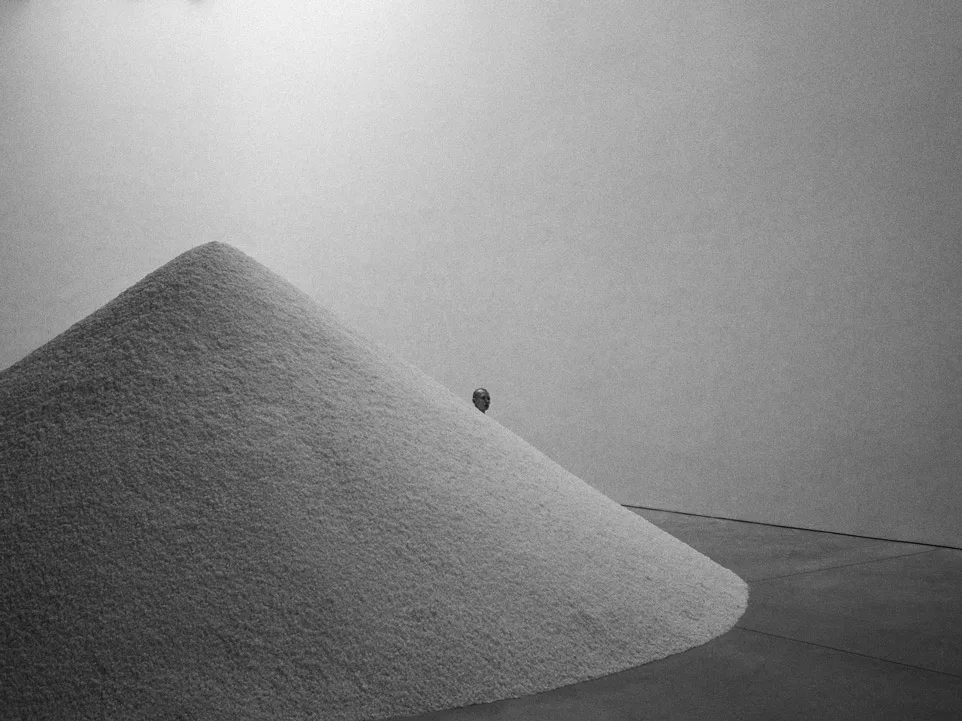

He silently circled a mountain of salt on his knees, dressed all in white, in complete silence, for eight hours a day, five days a week, over the course of a month

In his most memorable durational art work, nothingtoodoo, his solo debut at Mary Boone Gallery, he silently circled a mountain of salt on his knees, dressed all in white, in complete silence, for eight hours a day, five days a week, over the course of a month.

While critics speculated that white was chosen for symbolic reasons, Terence maintains it was purely a preference, a favorite color. “I don't explain; it's just not what I do,” he says. “It’s not that I don't want to talk about it because I'm gonna keep it a mystery, but because I really don't know. I the artworks just like life: It just comes and I do it. It's almost better that everybody experiences it themselves.”

His Bee Chapel is a meditation on connectedness

In 2014, Terence and his boyfriend, graphic artist Garrick Gott, left New York City to live in the Catskill Mountains upstate. “I remember there were so many shows happening. I was just constantly working and flying, and you don't even have the time to be introspective,” he remembers of his last days in New York.

“Instinctually, I knew that I had to go to the woods and recharge. We all have to go back to our personal selves in a way...go back to the womb – the womb of Earth itself – so that we can quiet our minds and listen to nature and, at the same time, listen to our civilization.”

This physical move brought with it a new sense of clarity and humility, and sparked an interest in the natural world that made its way into his practice.

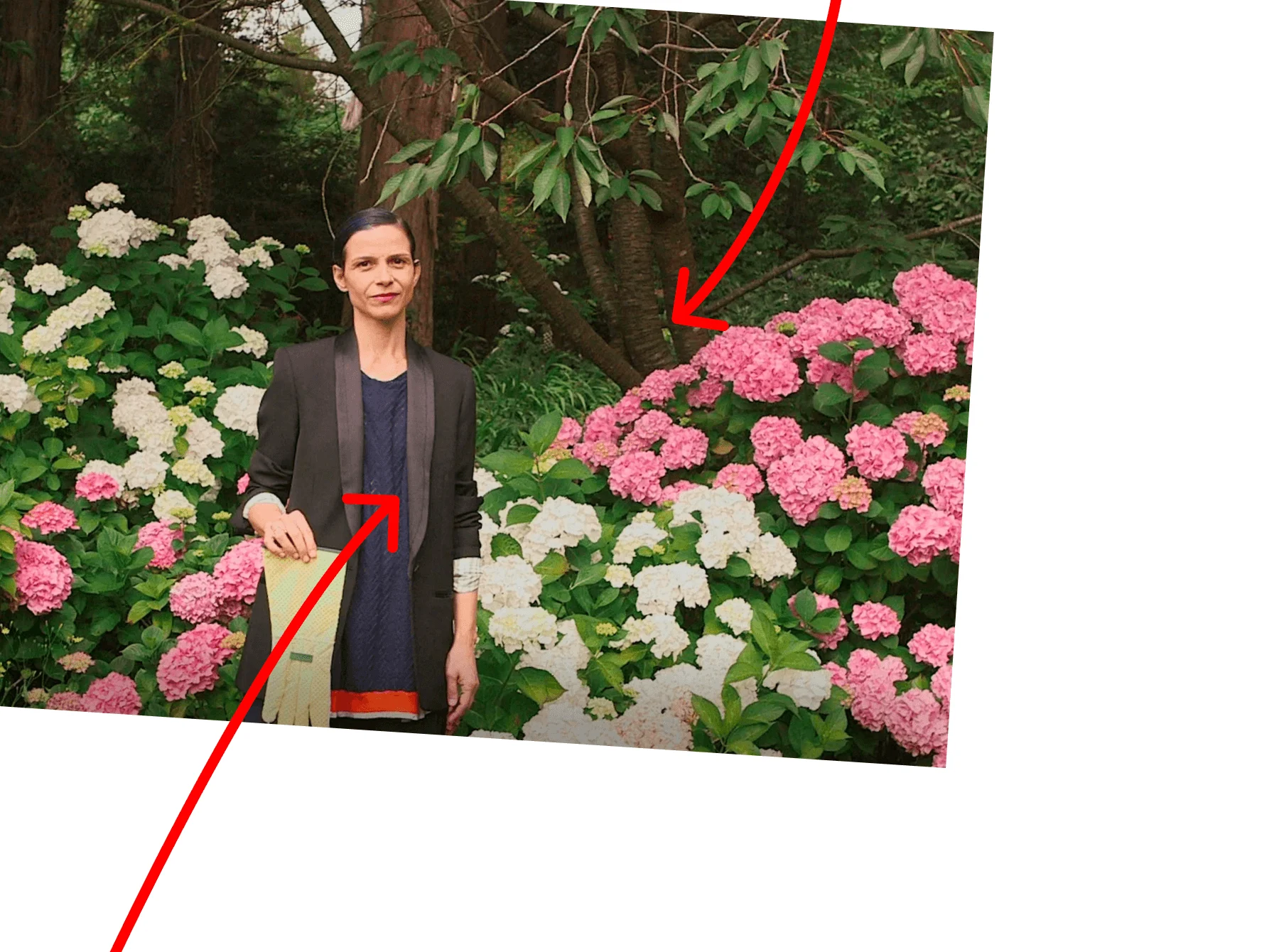

In 2015, in the Catskills, he created his first Bee Chapel: a small hut in which honey bees build honeycomb. Elevated on a wooden platform, it was just large enough for a single person to enter and observe the activity through a mesh veil, and was surrounded by a garden of flowers and glass-covered collages.

“There are other ways of thinking that you can see in a honeybee hive,” he says, referring to the organizational structures he’s observed within the chapels. “We can see different systems, and open up our minds to a civilization that has existed for way longer than . It's female-centric, but it's not hierarchical and it doesn't have the egos that we have, and somehow they communicate,” he says.

Since then, he has centered shows in New York, Los Angeles and Hamburg around such chapels, in hopes that visitors will look at our own societal structures more critically, and ponder our own interconnectedness.

He wants his audience to lose themselves in the moment

In August 2019, while his Bee Chapel was installed in Hamburg, Terence lived in a makeshift tent constructed next to a bridge nearby, complete with a bed, kitchen area and herb garden. For the duration, he was accessible at all times to visiting art-lovers and curious passers-by. “I think that was very beautiful for me and the visitors,” he says. “I was opened up there in a vulnerable setting, and when that, they perhaps instinctually opened up as well.”

He remembers watching a group of school children try to cram themselves into the Bee Chapel together, freely interacting with the work without self-consciousness, expectation or instruction – exemplifying the attitude Terence wants all visitors to approach his art with.

I think that someone can stop themselves for just that moment to lose themselves in time

He observed similar moments looking in on visitors at drummen, a 2018 exhibition where he filled Brussels’ Office Baroque gallery with dirt and lit a campfire in the center, as well as at his solo show at the Whitney in 2007, when he installed a blinding white light (Untitled) in the museum’s lobby. He hopes that whoever stumbles upon time.love, a simple online diary where he shares daily sketches and written reflections from his home in Southern California, along with photos, videos and quotes, will respond to the site in the same way.

“Whether they’re looking at a post on the website, or going to a physical space, or watching a video, I think that someone can stop themselves for just that moment to lose themselves in time,” he says. “If there's any purpose to my artwork, that would be it.”