Zanele Muholi is rewriting visual history and challenging the way we think about art. The Black, queer, non-binary activist (who uses the pronouns they/them/their) documents the disconnect at the heart of South African society – where marginalised communities face violence, prejudice and bigotry despite the country’s liberal reputation.

Their work is bold and confrontational – pointedly addressing race and the politics of pigment – but also tender, beautiful and loving, from self-portraits that explore themes of blackness and selfhood, to intimate photographs of LGBTQIA+ people of color.

Tate curator Kerryn Greenberg explains how and why Muholi’s work is so significant.

Yes, but why? is a project by WePresent and Tate galleries to explain what makes some of world’s best artists so brilliant.

They were born at the height of Apartheid

They identify as visual activist rather than an artist

Muholi prefers to be called an activist rather than an artist. Art, for them, is a means to an end, a tool to convey messages about social empowerment and visibility. “Zanele Muholi's visual activism is not an occupation. It's a lifestyle,” Kerryn explains. “It's something that occupies them day and night – whether they receive a call from someone in the community needing money to pay for a hospital appointment, or consoling those who've lost someone close to them in an act of violence, or giving some kind of public address at a wedding or a funeral. It's about being a very active member of the community, and a public voice within that community.”

Their work represents and empowers the LGBTQIA+ community...

South African attitudes to gender and sexuality are contradictory. It was the first African country to legalise same-sex marriage (in 2006) but the LGBTQIA+ community still faces extreme levels of violence and discrimination.

As a non-binary person, Muholi sees it as their duty to humanise what society names "the Other", in South Africa and beyond. In their work, this often means documenting a different side of an often marginalised LGBTQIA+ community.

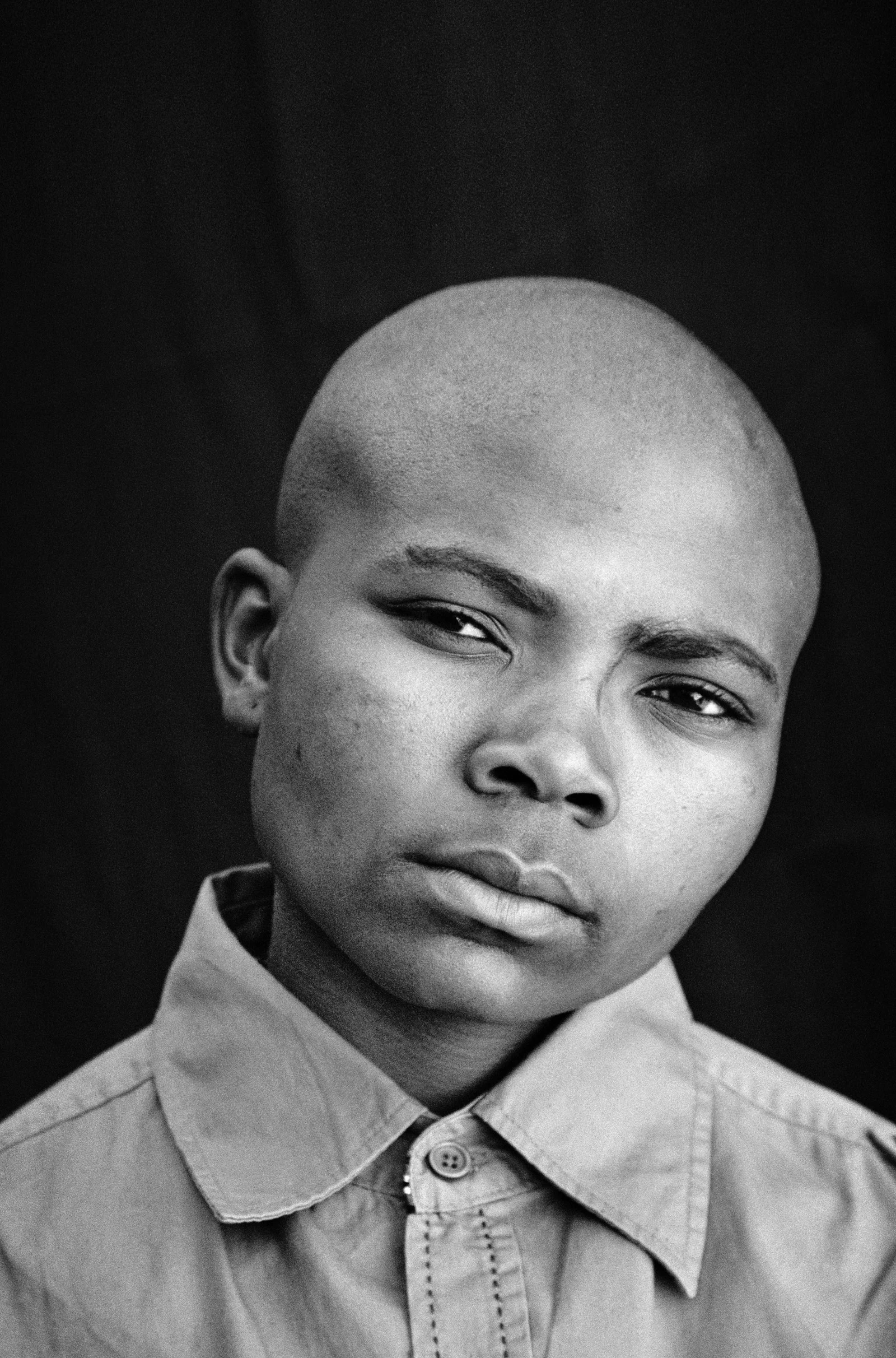

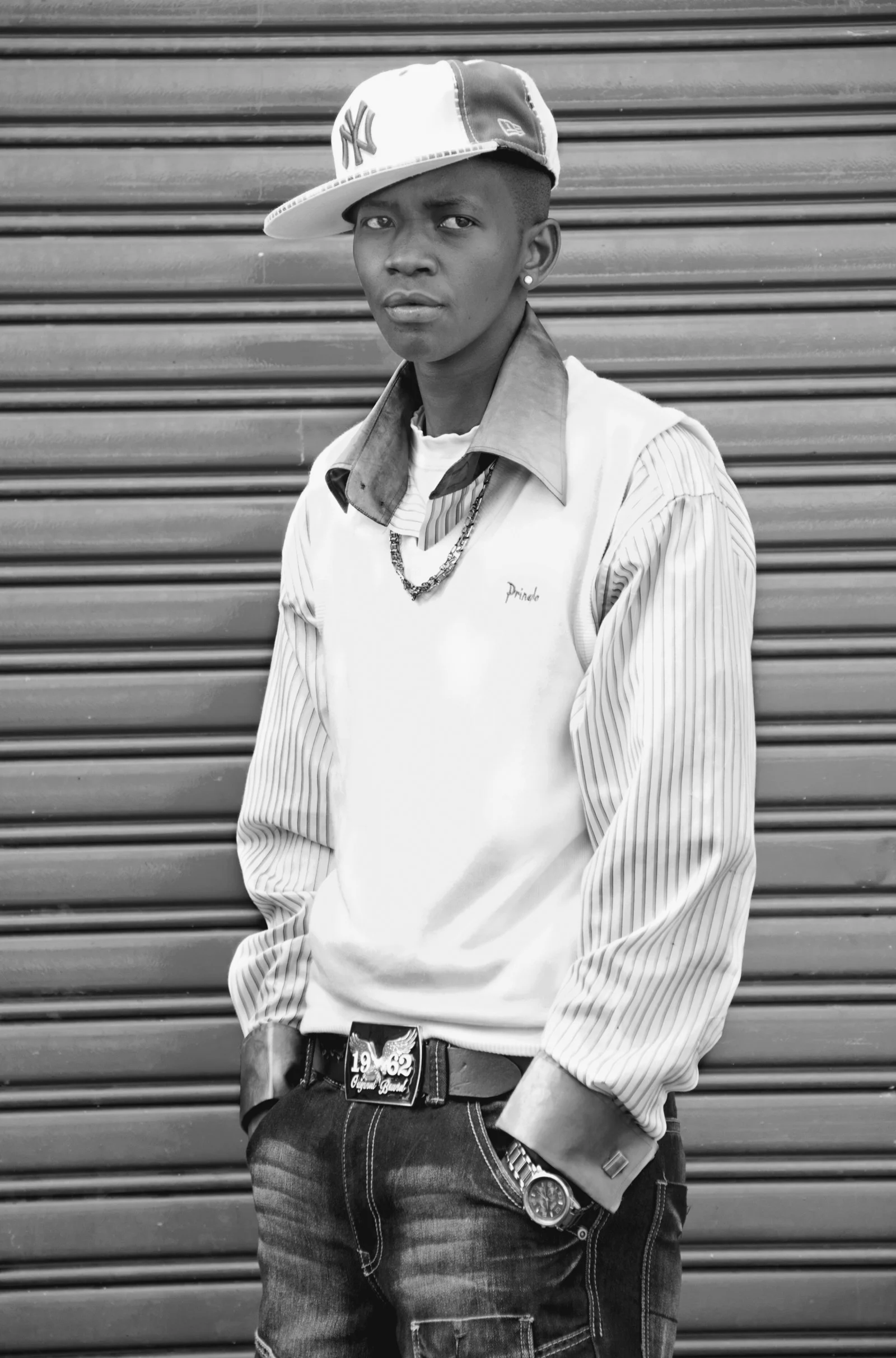

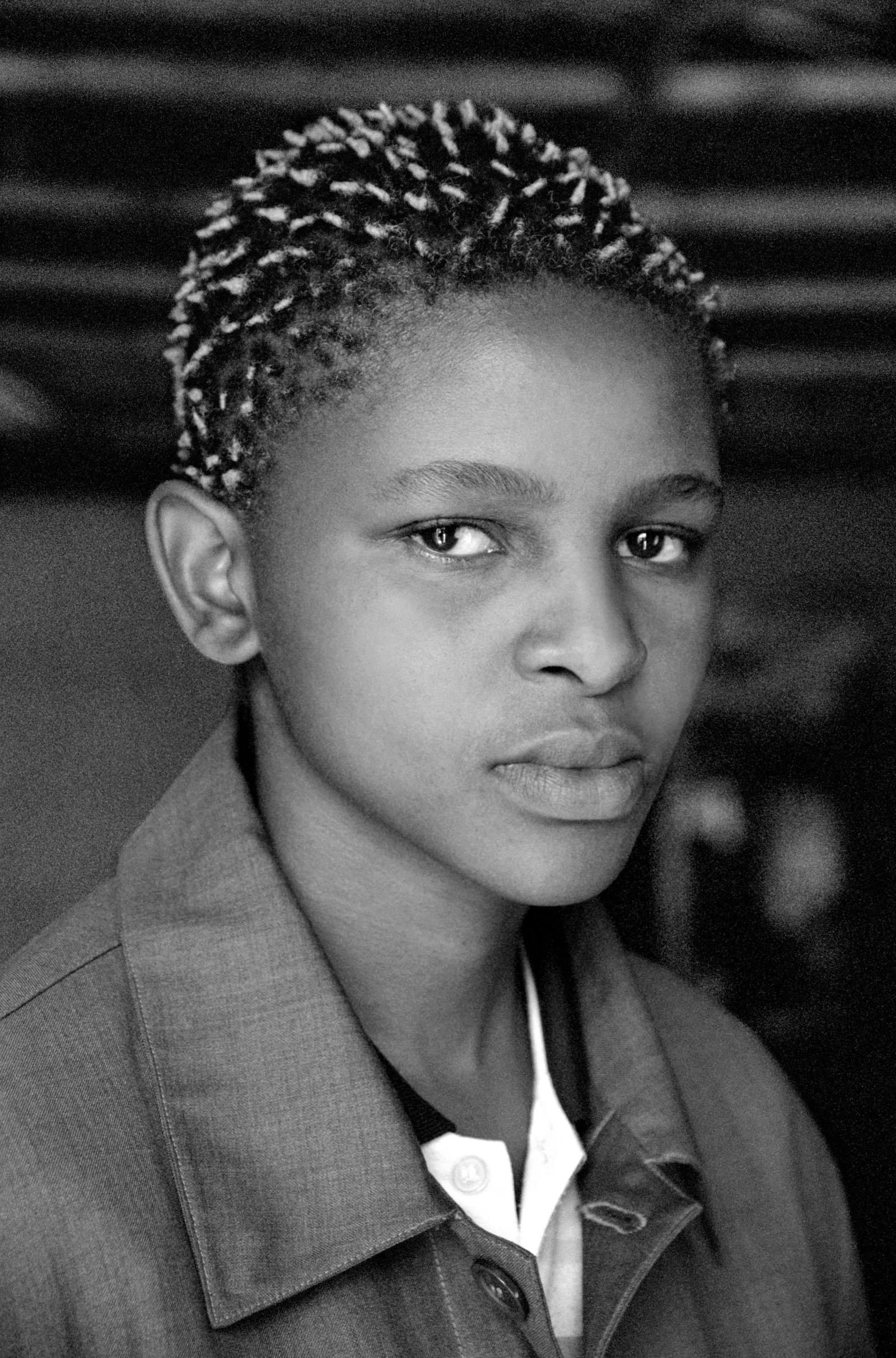

Take Faces and Phases, a bold and powerful series of portraits of black lesbian women and transmen created from 2006 onwards in Muholi’s home country and abroad. These photographs are by turns tender, joyful and determined. Black, queer narratives have often been ignored, dismissed or actively oppressed; Muholi reclaims the photographic image, and uses it to document people who’ve long been deprived a place in visual history.

...and they started grassroots collectives to support them

Muholi knows the power of bringing marginalised people together. In 2002 they co-founded the Forum for the Empowerment of Women (FEW), a black lesbian organization which provided a safe space for women to meet. Later, in 2009, they launched the Inkanyiso collective – which means The Light in Zulu – a media platform which features LGBTQIA+ people living in South Africa. Both help empower the communities to which Muholi belongs – collective representation as activism.

They photograph participants, not subjects

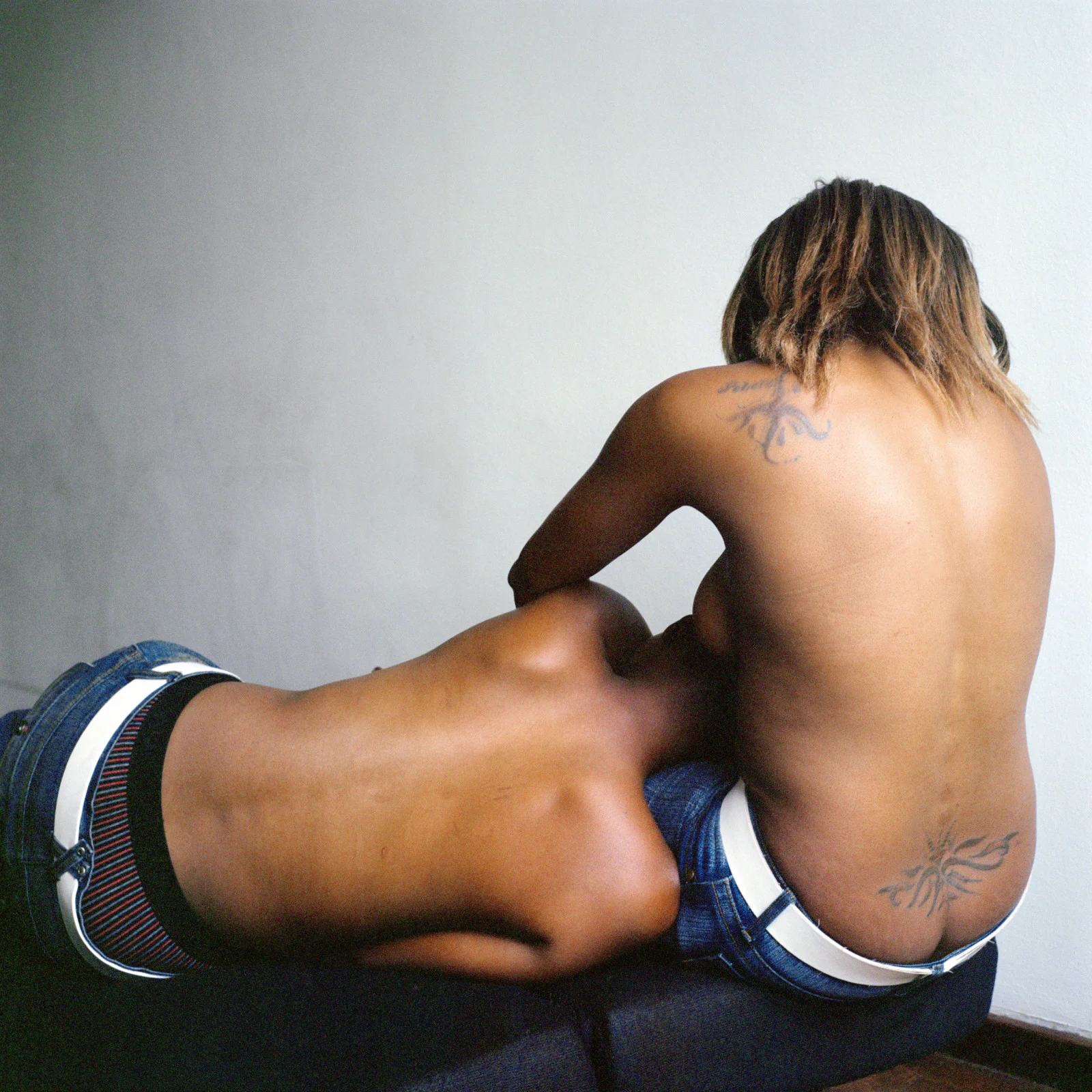

Their early series painted a new picture of lesbian identity

They celebrate the beauty of black skin

Many of the early pioneers of photography were white, and most of them didn’t spend much time thinking about how the new art form might capture black skin with the same depth and richness of tone as it did white skin.

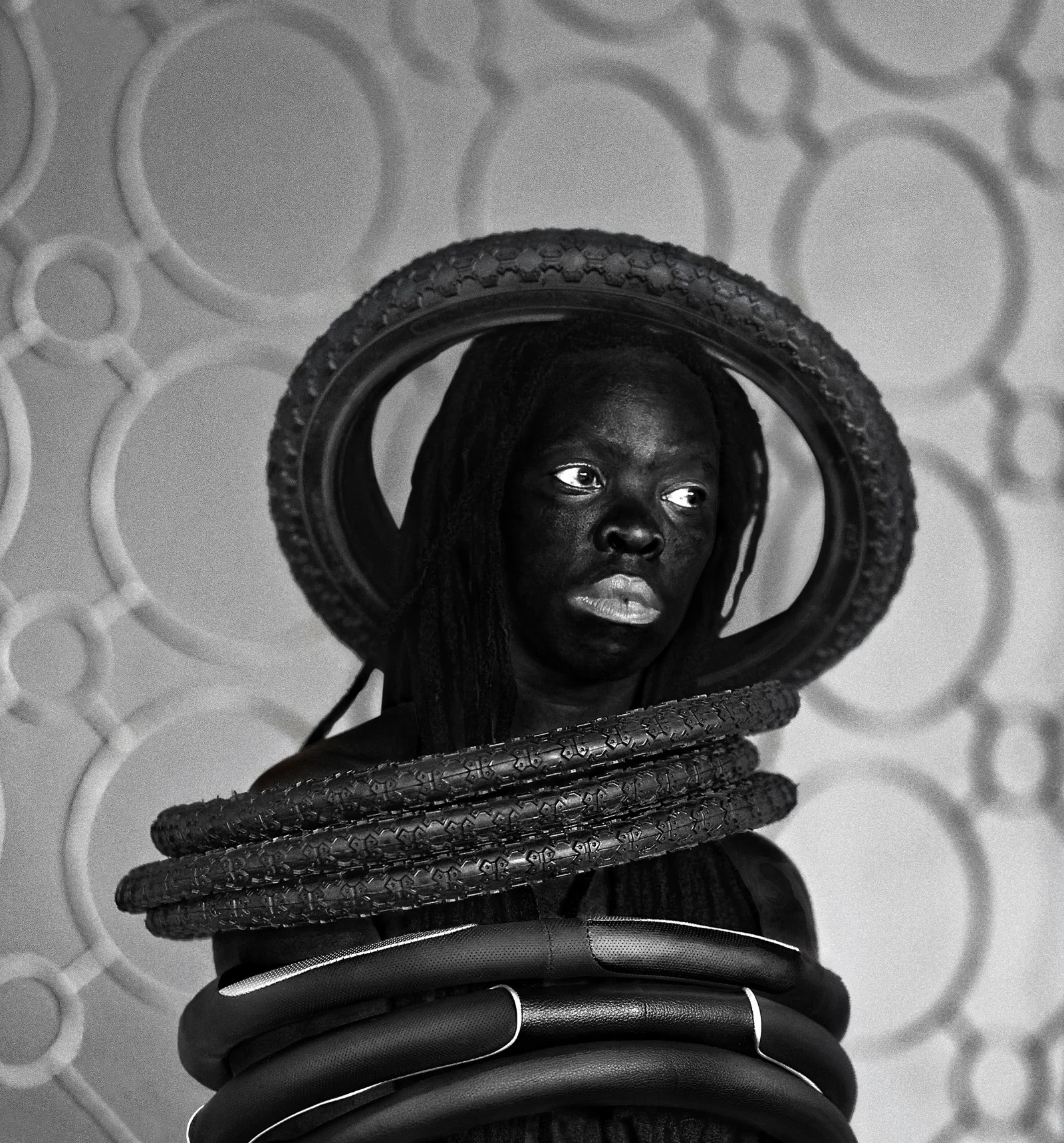

Muholi likes to play on this cultural history in their work. Though color images crop up from time to time, they mostly shoot in black and white, and the deeply-saturated dark tones seem to stay imprinted on your eyes long after you look away. "I'm reclaiming my blackness,” the artist has written, “which I feel is continuously performed by the privileged other.”

They create powerful self-portraits shot around the world

Their relationship with their mother is very important

Muholi’s mother Bester – who worked in the home of a white South African family for more than 40 years – appears time and time again in their work, for example in the household items featured in the powerful Somnyama Ngonyama self-portrait series.

Muholi pays respect not only to their own relationship – Bester died in 2009 – but also to ideas around personal history and collective memory. Within their community, Muholi, too, plays the role of a parent – as well as that of “nurturer, consoler, guardian,” Kerryn says.