Olafur Eliasson has changed what it means to be an artist. His work straddles architecture, ecology, food, education, sustainability, climate change, perception and collective activity. This may sound very serious, but there is a sense of wonder that runs through his work which helps explain why it speaks to so many different people all around the world.

From his childhood in Iceland to his unlikely passion for breakdancing, his fascination with weather to the climate change activism that’s inspired world leaders, Tate curator Mark Godfrey talks us through Eliasson’s enduring influence.

Yes, but why? is a project by WePresent and Tate galleries to explain what makes some of world’s best artists so brilliant.

He’s inspired by Iceland to connect nature and art

Olafur Eliasson was born in Denmark in 1967, but spent a lot of his childhood in Iceland, where his parents were from. Iceland's wild landscapes had a powerful impact on the artist – its hot pools, lava fields, volcanoes, waterfalls, caves and moss banks. His later work included rainbows and clouds of steam, recreating some of the things that enchanted him as a boy.

In Iceland, Eliasson also became interested in the ways we experience space, for example how you can work out how far you are from a waterfall by the speed at which its water appears to be moving. In this environment every sense comes into play – just as it does in his later installations.

Eliasson went on to study at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in the late 1980s and early 90s, where he experimented with light installations. By making work that relied on lived experiences – in short, pieces that are more difficult to buy and sell – he resisted the commercialism driving the art world at that time.

He was Denmark’s breakdancing champion

He wants you to see how it works

Through the 1990s and early 2000s, Eliasson made work that recreated natural phenomena.

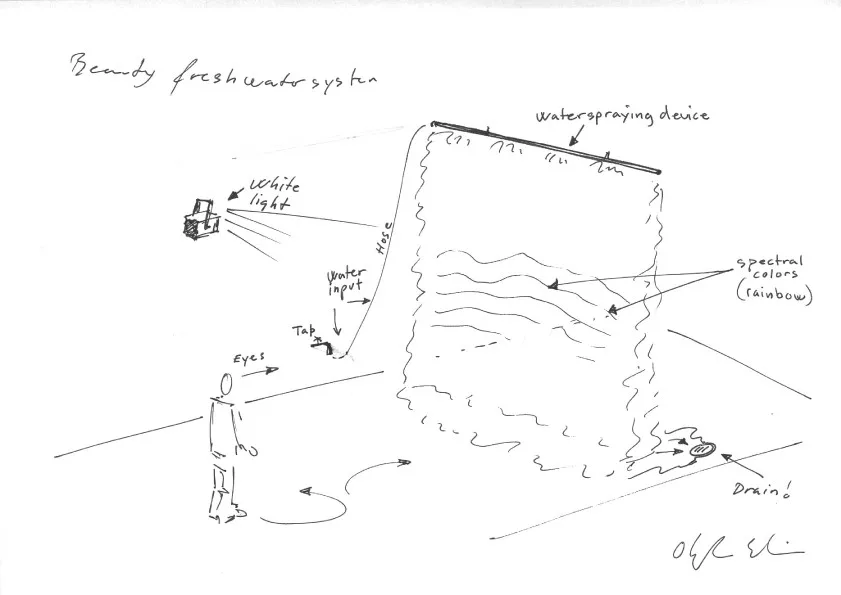

Take 1993’s Beauty, for example, a work within a black box art space. "You walk into a room. It’s darkened. There's a fine mist falling out of a punctured hose pipe, but it’s illuminated by a single light bulb,” Mark explains. "From some angles, but not from all angles, there’s a rainbow.”

In this piece, as in others, Eliasson wanted to recreate something he’d witnessed first-hand in Iceland, but he didn’t hide how it was done. “You saw the hose pipe, you saw the spotlight, you saw the things creating the rainbow even as you saw the rainbow,” Mark says.

Underpinning it all is an interest in the process of perception, and making his audience aware of that process. “He called it seeing yourself sensing. You'd not just be having an experience, but conscious of having that experience. You would be made self-aware by the set-up of his work, of that experience of looking.”

And he was always driven to see how people took this awareness out into their lives. “He was interested in the connection between an experience that might take place in a gallery and the way it might affect your behavior when you leave that gallery in relation to the world around you,” Mark explains.

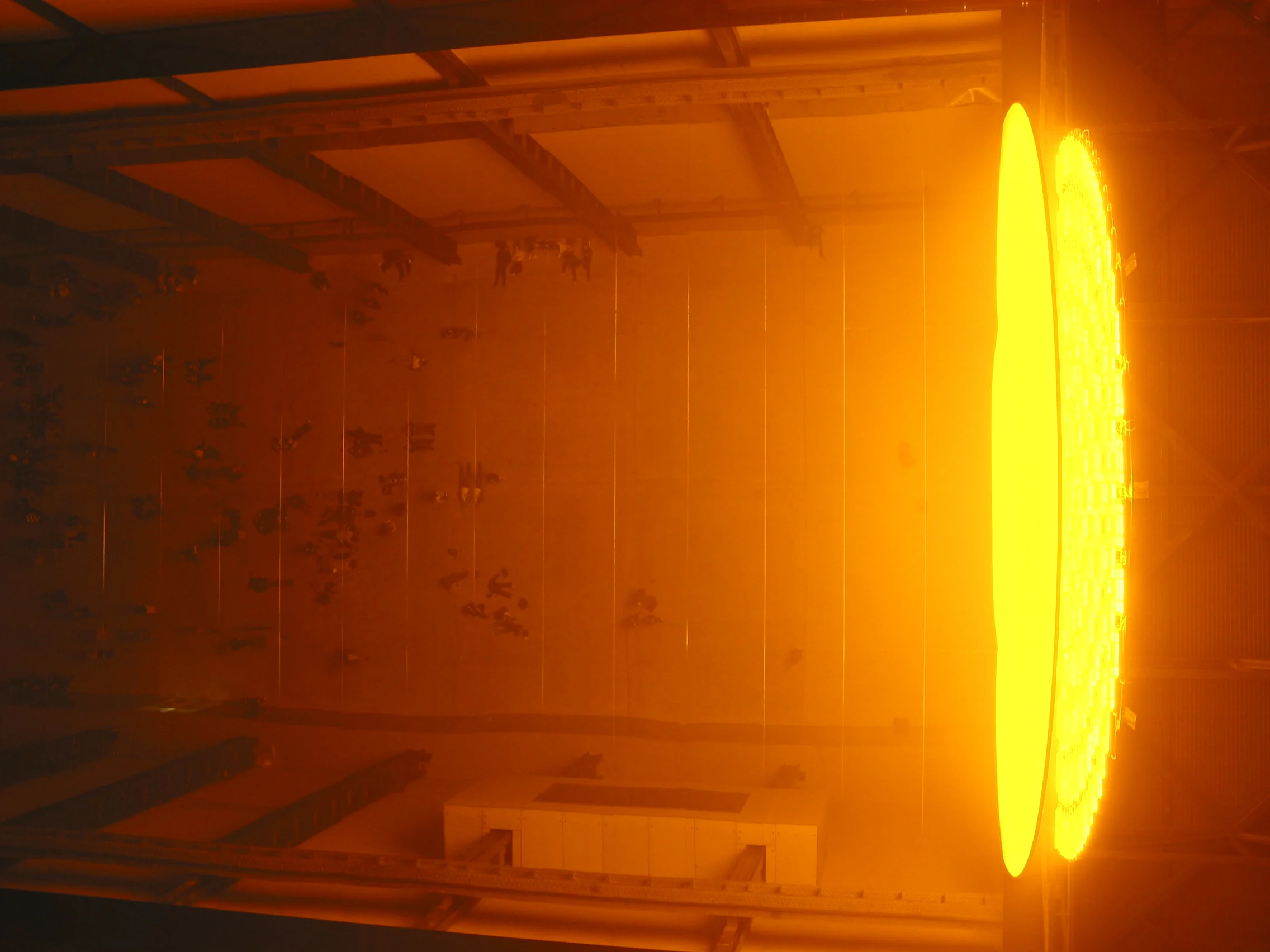

He changed art forever with The weather project

He wanted to create the illusion of a meteorological event – a sort of big sunset.

His Little Sun brings light all over the world

Little Sun’s aim is to facilitate a lot more than just having a source of light in the evening.

He scales up to create eye-catching buildings

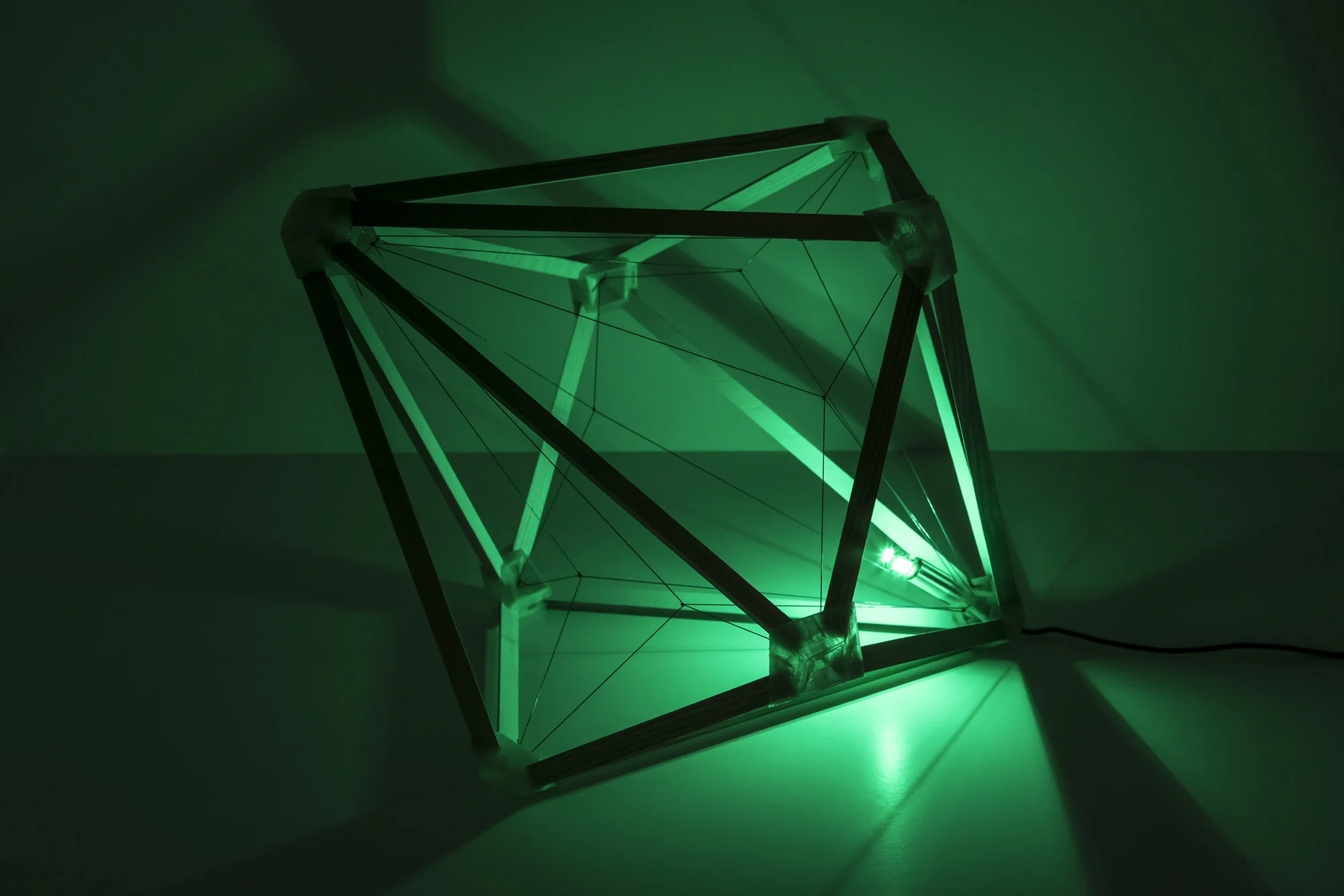

How do we navigate a room? It’s a question that’s been key to Eliasson’s work since his earliest experiments, changing spaces by altering shapes or using unusual lighting.

In 2014 he teamed up with architect Sebastian Behmann to found Studio Other Spaces (SOS), “an office for art and architecture” that uses an “experiment-based approach” to drive forward its innovative projects.

SOS grew out of Eliasson and Behmann’s work together on projects like the awe-inspiring geometric façades of Harpa Reykjavik Concert Hall and Conference Centre, and Fjordenhus – an extraordinary fortress-like building in the middle of a fjord in Denmark.

His studio revolves around the kitchen

Studio Olafur Eliasson is a collective of 100 or so people, based in an old four-storey brewery in Berlin. It’s a place of immense experimentation, collaboration, conversation and multidisciplinary making, Mark explains, employing craftsmen, technicians, researchers, administrators, cooks, programmers, archivists, architects and filmmakers.

On the top floor is the studio’s kitchen where everybody eats together four days a week. The food, prepared on-site by a dedicated team, is organic, locally sourced, and always vegetarian. “Olafur's sister is a chef, so I think he's always been interested in cooking and in food,” Mark says “and it runs through the work in more ways than one.”

He is keen for his art to address climate change

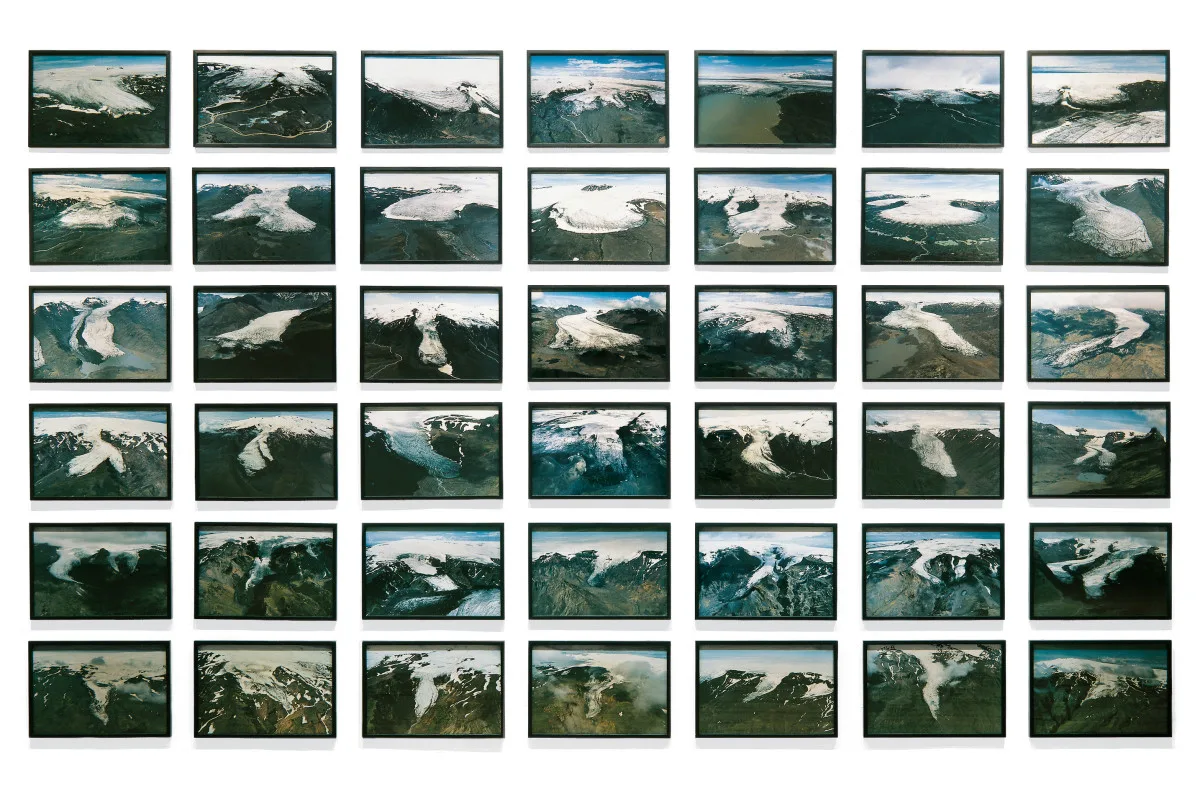

Ice Watch is his attempt to make the crisis of climate change tangible for people.

He is always open to new opportunities

Hope is at the core of Studio Olafur Eliasson, an optimistic drive to make the world a better place.

Everyone he meets, from politicians and business leaders to choreographers, chefs and scientists, presents an opportunity. The starting point is the same – meet people, listen to them and see how you might work together in the future.

For example, a chat about climate change with former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg led to Ice Watch, where Eliasson and geologist Minik Rosing put real blocks of glacial ice on display in Copenhagen, Paris and London.

Yes, but why? is a project by WePresent and Tate galleries to explain what makes some of world’s best artists so brilliant.