Email lingo and etiquette has been grating on our nerves for years. It’s a part of the working day which is a cruel, difficult-to-get-right necessity. From cheeky autoresponders to lame sign-offs, it’s a cringeworthy minefield of dos and don’ts. Writer Seth Fried explores the groan-inducing world of email clichés.

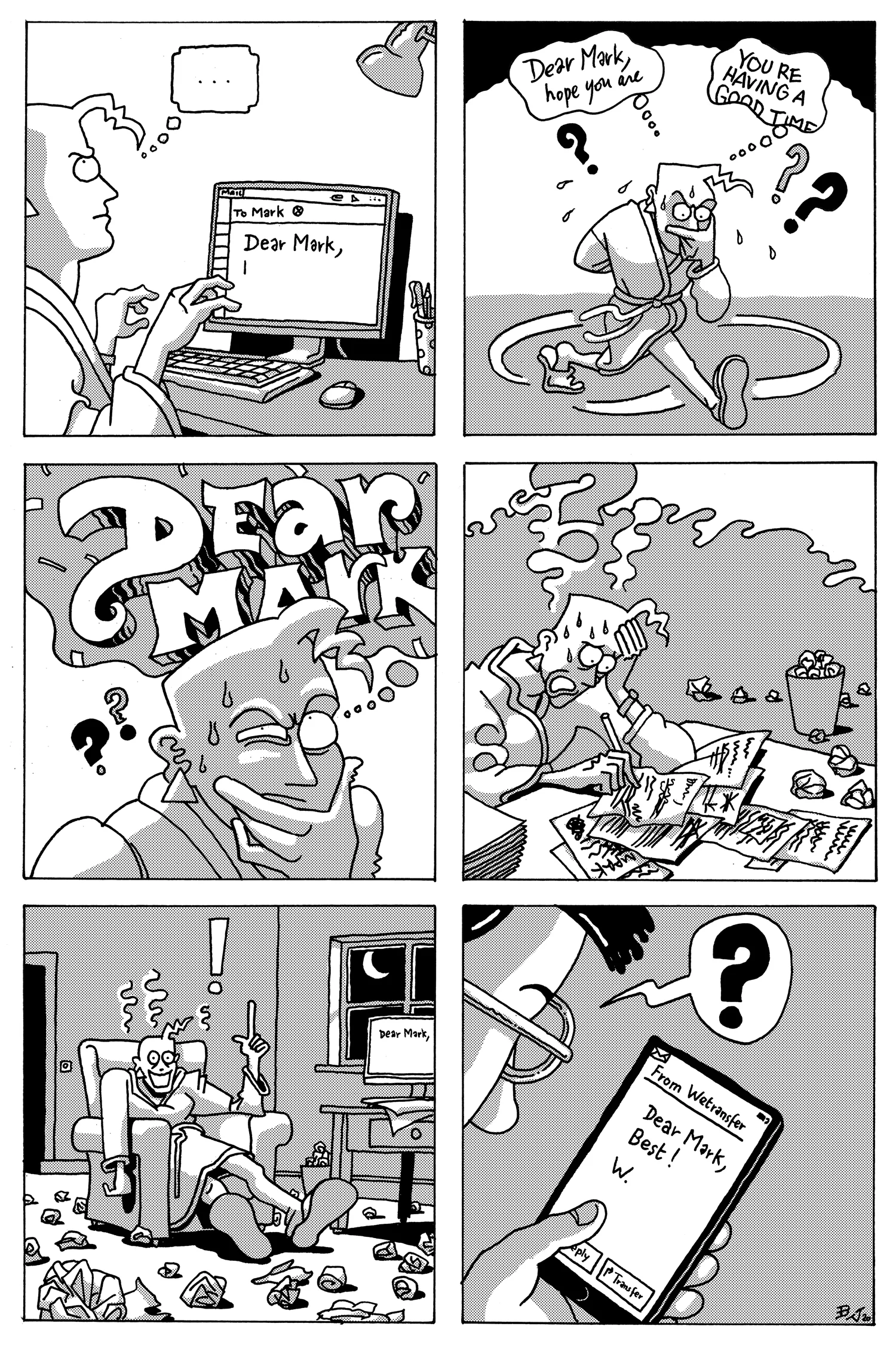

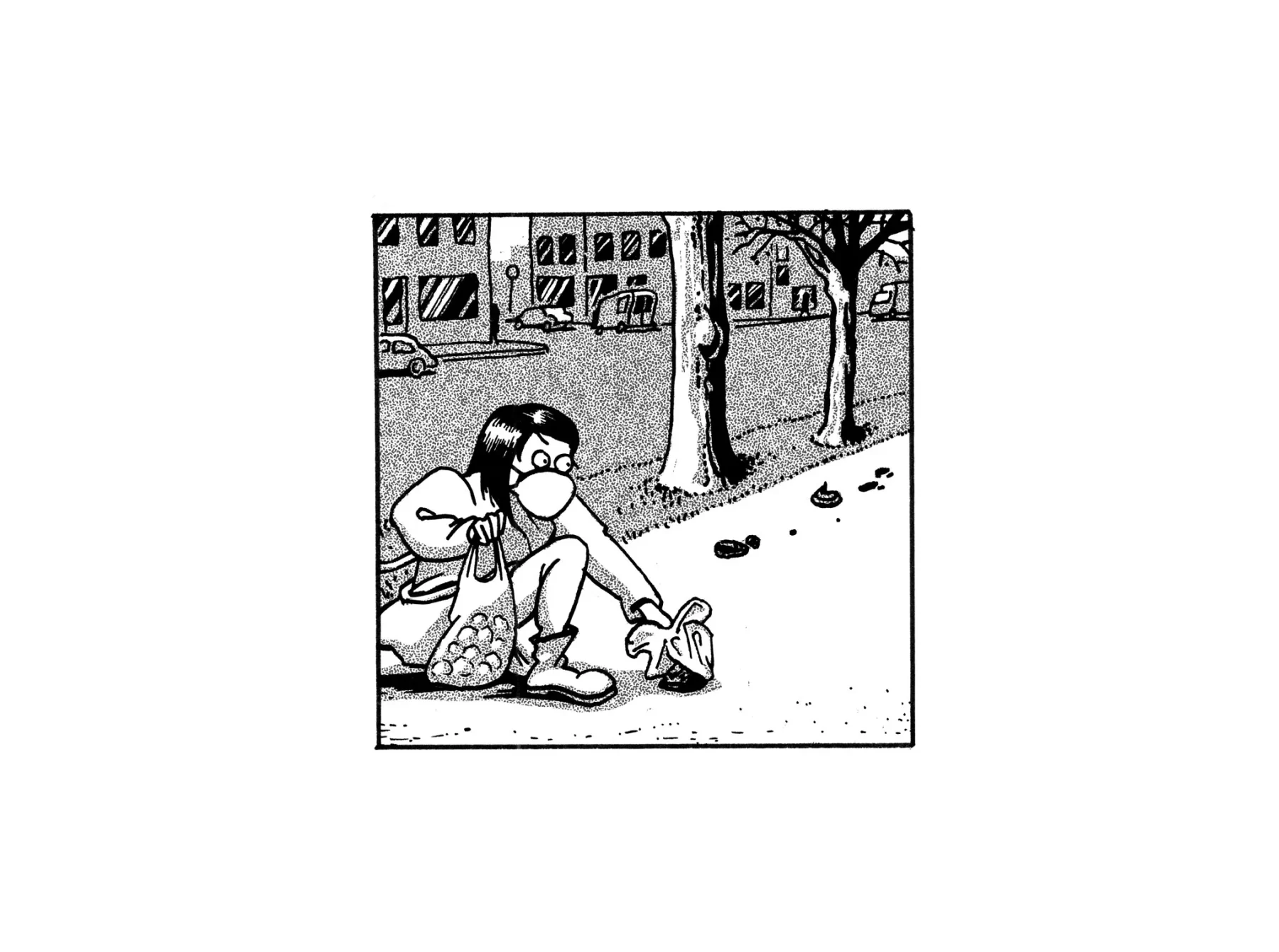

Comic by Baptiste Virot

Re: Work Email, In Praise of Clichés

I hope this essay finds you well. If your job involves any amount of email, then the cliché I just used probably tells you two things. The first is that you don’t know me very well. The second is that I’m about to ask you for something. Allow me to clarify both points: I am a writer who thinks the clichés that get used in work emails are not only useful but often elegant solutions to complex professional problems. What I’m asking for is that you hear me out.

If you search the phrase “email clichés,” you’ll find dozens of articles suggesting you avoid phrases like “hope all is well,” “just following up!” “I wanted to reach out,” “per our last email,” and many others. The criticisms typically levelled against these expressions are that they are bad writing, annoying, and insincere.

I hope this essay finds you well.

Let’s start with the obvious. Clichés are bad writing, right? There are a lot of interesting dichotomies that can be used to discuss writing, but good vs. bad is as problematic a way to discuss writing as it is any other topic. “Good” and “bad” are arbitrary goalposts that vary from person to person and can be redefined at any time for any reason.

When I teach creative writing, one of the first ideas I try to introduce to my students is that writing can be viewed on a spectrum with clarity on one end and creativity on the other. These qualities might not seem mutually exclusive, but in their extremes they are. If I’m drafting the opening of a short story and I write that it was a cold night in Winnipeg with a moon that was low and full, I’m not being very creative, but I am being clear. On the other hand, if I write that the moon over Winnipeg was the face of a lonely prince looking down on the woes of man as if they were the playthings of his forgotten youth, I am being creative, but as far as clarity goes I might as well be writing the story in Old English.

Even in a simpler and more refined metaphor, clarity is sacrificed for something more expansive and enigmatic. When John Donne calls the rising sun a busy old fool, we’re transported by the impression this conveys precisely because we aren’t able to say exactly what he means. Instead of providing literal information, the description has become a collaboration between writer and reader, with readers now forced to make that comparison in their imaginations.

A cliché might not be pretty, but neither is a nail gun.

Presented with this view of writing, many students tend to ask which approach is preferable. In creative writing, there’s no right answer. I tell my students to ask themselves what kind of experience they want their readers to have. Do they want readers to feel drawn into a grounded, continuous world? Do they want readers to be pleasantly bewildered by something ineffable? It's the dealer's choice. But in professional correspondence, we do have an answer: clarity is the only thing that matters. A cliché is by definition an expression that is overly familiar, and so, while it lacks originality, its meaning is immediately clear.

Though that does little to insulate clichés from the claim that they’re annoying, which at first glance they would certainly seem to be. Email clichés are the delivery system through which we receive the passive aggression of our coworkers (“FYI, best practices moving forward”), the news from our collaborators that they’ve flaked (“sorry for the radio silence”) or from anyone letting us know that we’ve flaked (“just following up”). Email clichés are annoying the way an alarm clock is annoying. We hate the noise our alarms make because we don’t want to get out of bed. If I were to change my alarm to soothing whale noises, I might enjoy it more. But if I end up spooning my alarm clock and half-consciously making whale noises back at it, that’s not going to do anything to address the actual stress of starting my day. Likewise, the idea that email clichés themselves are what’s annoying, that people need to replace them with original turns of phrase that will then have to be newly interpreted, just makes workplace communication take more time and energy, thus exacerbating the actual problems which cause you to feel frustrated in the first place.

If I end up spooning my alarm clock and half-consciously making whale noises back at it, that’s not going to do anything to address the actual stress of starting my day.

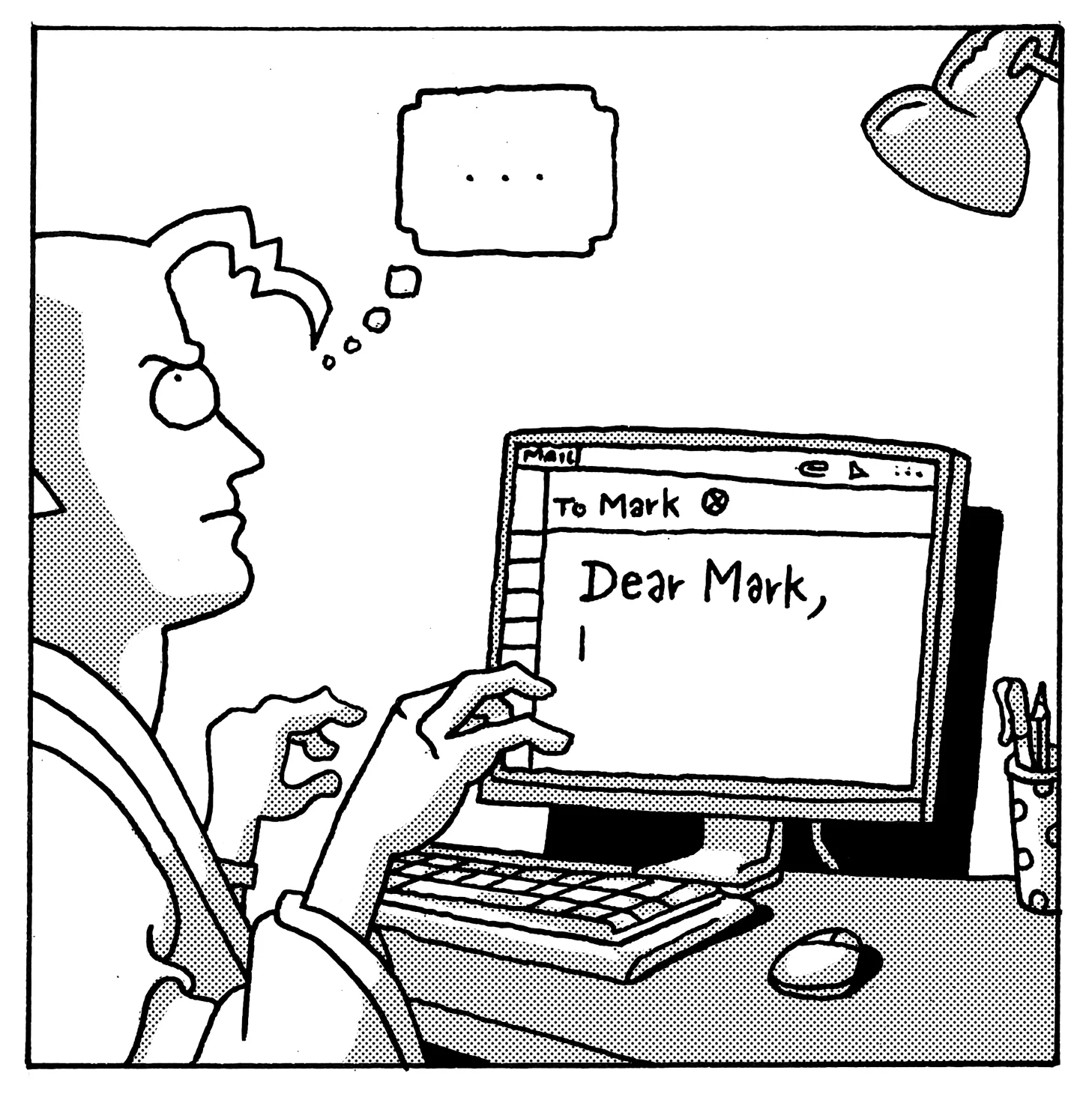

A more valid criticism would be that clichés are insincere. After all, when I write in an email that I hope someone is well, I am not literally sitting at my desk, rocking back and forth while I beg the universe to spare the recipient from the stream of unrelenting torment which is every sentient being’s daily burden. I’m just being polite. Or rather, I’m indicating to the recipient that, though I don’t know them personally, I believe they deserve to be approached with politeness even if only because they’re a human being. Phrases like “I hope you’re well” or “I hope this finds you well” are fast, efficient ways to get this sentiment across without being awkward.

Just consider the sort of weird emotional energy that would have to go into making the claim “hope you’re well” feel literally true.

Dear Marcus,

Before writing this email, I decided to get to know you a little by spending some time on your various social media profiles. Right away, I have to say that I admire your devotion to your fiancée, Amber. Also, I can already tell you two are going to be wonderful parents based on how you dote on your incorrigible rottweiler puppy, Zappa (is that a reference to the musician?). I was also saddened to learn about your stepfather’s recent health issues. I hope he’s feeling better. Knowing everything that I know about you and sensing from that your general goodness, how could I start this email by doing anything other than hoping this email finds you well?

Also, if you could send me a pdf of last quarter’s P&E, I would greatly appreciate it.

Best,

Seth

Or maybe it would just be better to use an agreed upon pleasantry.

I don’t expect people to be excited to deploy an email cliché, anymore than they should sprint down the halls of their offices singing show tunes at the idea of using a paperclip or updating a spreadsheet. But as a person who’s devoted his entire adult life to the pursuit of writing, the main thing I’ve learned is that there are no perfect solutions. A quote I often share with my students is Aristotle’s, “a friend to everyone is a friend to no one.” Likewise, a piece of writing that attempts to live up to every possible standard won’t end up being much of anything. Good writers train themselves to seek out and recognize the goal of a specific piece of writing and then organize their decisions around that aim. To use a cliché in defense of clichés, you have to use the right tool for the job. A cliché might not be pretty, but neither is a nail gun. Of course this is just one writer’s opinion. All I ask is that you give it some thought. Thanks in advance.