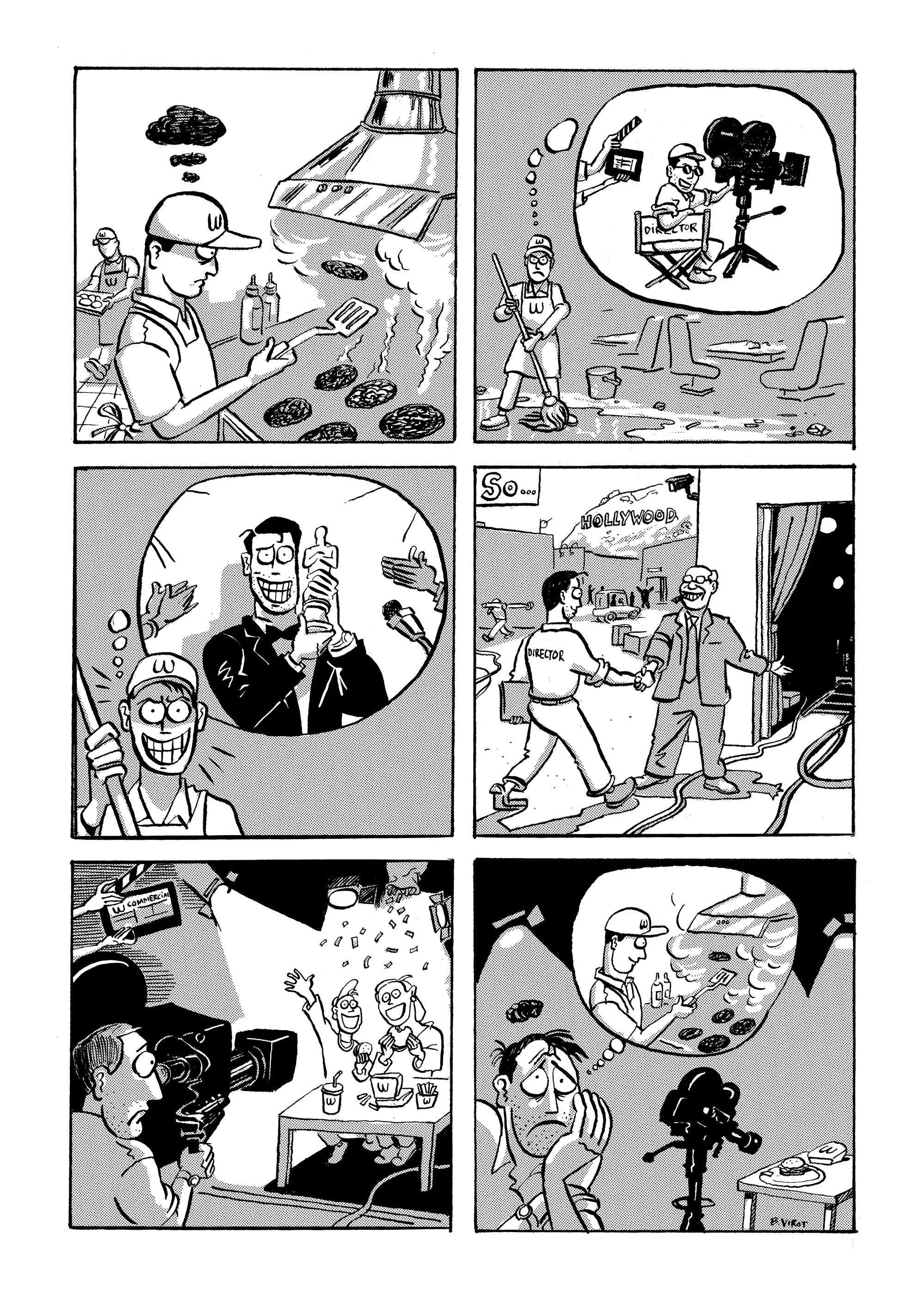

Graydon Sheppard has worked his share of jobs, from flipping burgers and pumping gas to bar-backing and bank-telling. And yet it’s his glamorous, highly paid gig directing TV commercials that he hated most of all. Here, the writer and filmmaker explains why he gave up the job a million art school grads would kill for—with no regrets whatsoever.

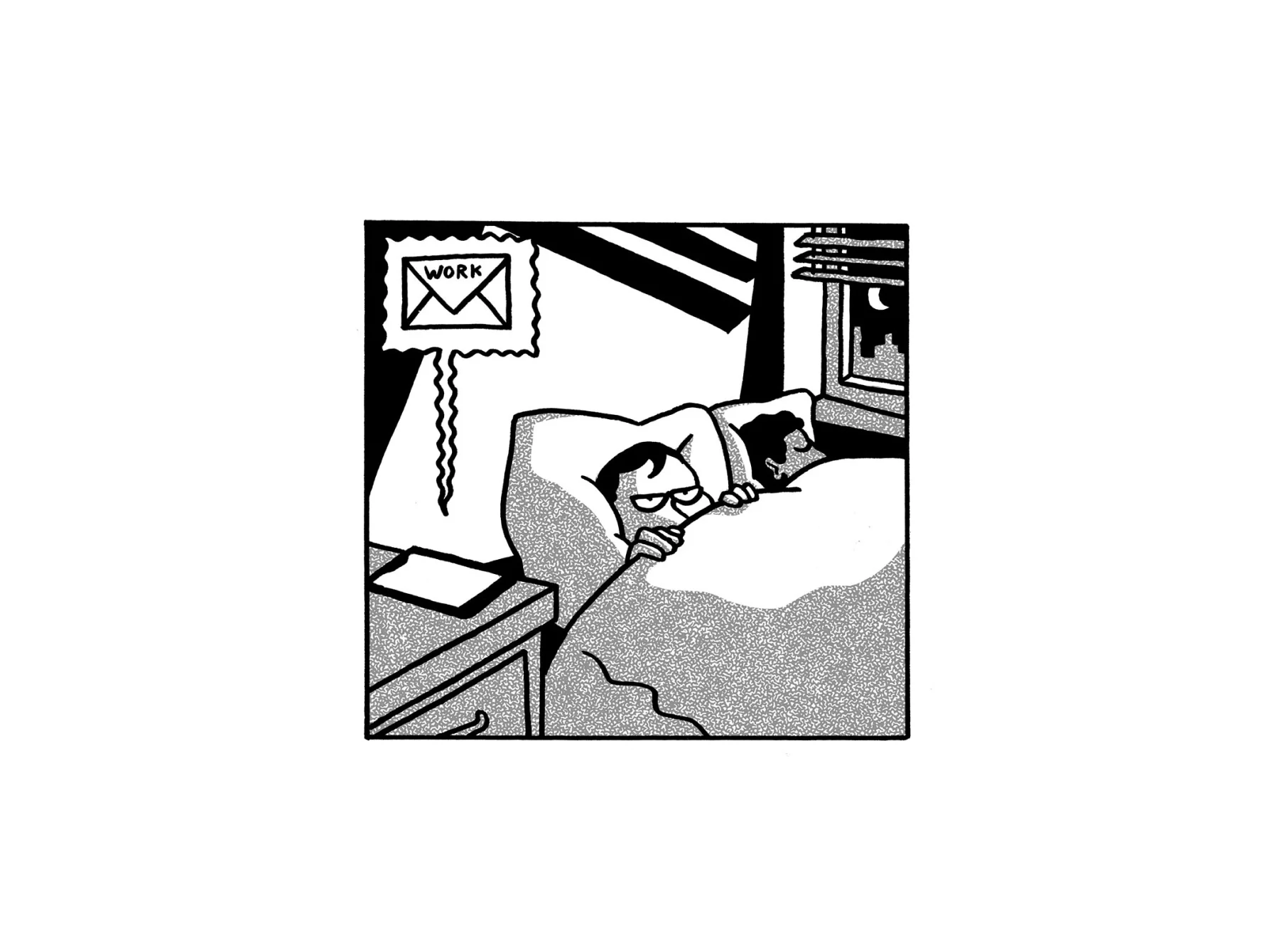

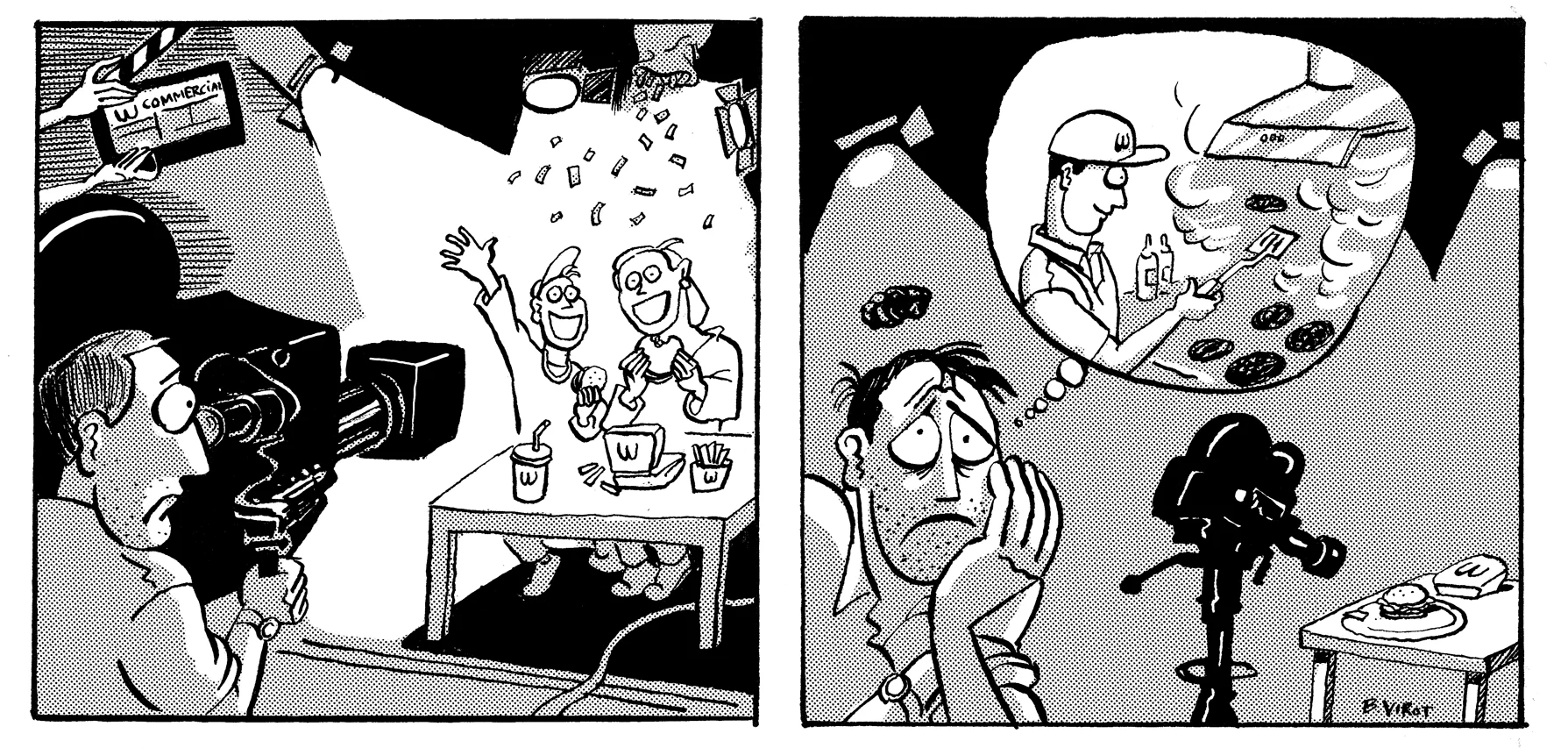

Comic by Baptiste Virot.

Being a commercial director is a highly coveted job. There are promises of huge paychecks, parties in the south of France, big-budget cocaine dinners, the chance to work with celebrities, and opportunities to “flex your directing muscle.” The flip side is that it might make you want to kill yourself, which is where I was headed when I finally decided to quit.

My commercial directing career started when I was fresh out of university, with a BFA in photography. I was plucked up by an established company who wanted to represent unconventional directors. I’d only been on film sets as an assistant before that, so it was a giant leap, and one that I was very proud of.

In the beginning, it was all very exciting. I got to travel to Tokyo and Copenhagen (where I had my first cocaine dinner, yum yum) and New York. I spent my entire per diem on a pair of jeans at Opening Ceremony because I didn’t understand what a per diem was. Pretty quickly, a campaign I directed won a Cannes Lion—a huge award that absolutely nobody outside of the ad industry gives one single shit about. I was told I’d be making at least $100K annually to start (to START!), and my 22-year-old brain was already purchasing vacation property and deciding on the color of the hot tub I would install.

I didn’t have the option of turning down a bad script.I literally could not afford to be picky.

A year later I’d only made a total of $14,000 (Canadian, before tax) and the company dropped me on my ass. It was both embarrassing and a relief. It helped me realize that I didn’t really know what I was doing on set, so I decided to go back to school and do an MFA in Film. Soon after that, I co-wrote, directed, and starred in a viral sensation. This truly changed my life and opened up the world, but it also sucked me back into commercial directing. “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.”

“This time directing commercials will be different,” I thought when I moved to LA. And it was different. At one point I was represented by five different commercial production companies around the world. I was on rosters alongside Sofia Coppola and Wes Anderson. And I was absolutely way out of my league. I was still considered a “build” director, someone who didn’t have much work and still needed to establish my reel. In other words, I wasn’t a Sofia or a Wes, directors with insanely high rates who have jobs offered to them without having to pitch.

If you don’t know how commercial jobs work, you’re not alone. I’ve explained it to my family about four hundred times and it still makes no sense to them, because it really makes no sense at all. But I’ll try again, in “Mad Men” terms:

A client (Coca-Cola) hires an ad agency (Sterling Cooper).

A creative director (Don Draper, of Sterling Cooper) writes a commercial script for Coca-Cola.

Several production companies submit a bunch of directors’ reels to Sterling Cooper in the hopes of getting the chance to compete for the Coca-Cola commercial.

Sterling Cooper chooses three directors (one of whom would be me, if I was lucky) to pitch on the Coca-Cola commercial script. (This is called “being shortlisted.”)

My producers and I pitch my vision and submit a proposed budget to Don Draper at Sterling Cooper.

Sterling Cooper recommends the director they like the most to Coca-Cola.

Coca-Cola approves that director, or just chooses another director because they’re the client and they do what they want.

The job is awarded and production begins.

Complicated, right? By the time I was shortlisted on a project, I felt like I had to do it. Not just because my reps had done a lot of work to get me on that shortlist, but also because it had usually been months since my last job, and I really needed the money. Yes, the paychecks were good, but they often just paid off credit cards and taxes and past-due bills, and then kept me afloat for about a month before the whole cycle started again. I didn’t have the option of turning down a bad script.I literally could not afford to be picky.

And to me, every script was bad. My heart would sink when a script would come in because I just knew it would be lame and I knew I’d have to pitch on it because, you know, rent (notice how I didn’t say mortgage). Perhaps the lamest commercial I directed featured a woman in a dress that was made of actual toilet paper dance-fighting with a man over the last package of “bathroom tissue” in a grocery store. (We were warned not to call it “toilet paper” in front of the client, as they had fired people for doing so on previous jobs).

“This is really great creative,” I’d hear from my reps. “Is it?” I’d think. “This is what you think is good? This excites you?” And on top of it all, the “better” the script, the more competitive the bids, and the more I’d be asked to lower my rate so that we could be financially competitive in getting the job.

I couldn’t look people in the eye and convincingly say, ‘I love this McDonald’s script! Especially the part where they bite the hamburger and smile! Great writing!

Every once in a while, between the commercials for toilet paper and fishsticks and discount outlet malls, there was a job I was proud of. One was a public service announcement that I directed to promote a program for free community college in America. This was in the final days of the Obama administration, and I got to go to the White House and direct the President himself. It was a career highlight. And guess what? I did not get paid a single cent for the several weeks of work and travel and prep that went into it. (Yes, it takes weeks—sometimes months—to make a simple commercial.)

Thirteen years after directing my first commercial, I finally realized that I didn’t want to direct other people’s horrible scripts any more—and other people realized that I was not very good at directing their horrible scripts either. I wasn’t good at spinning shit into gold, which the best commercial directors can do with their pride tied behind their back. I couldn’t fake it. I couldn’t look people in the eye and convincingly say, “I love this McDonald’s script! Especially the part where they bite the hamburger and smile! Great writing!” It’s just not in me, and they could tell.

With every job I lost, every pitch I flubbed, every commercial that just turned out “OK” or got shelved because I fucked it up, my confidence plummeted. My reel was all over the place and never good enough. Personal projects that I had made and loved were deemed useless in the commercial world. The things I wanted to do in commercials were never the things I was allowed to do.

By the end, I hadn’t shortlisted or seen a single script in almost a year, and I was burnt out—and believe me, you can get burnt out from the stress of not working just as much as you can from the stress of working too much. My finances were in shambles. My personal life was falling apart. My mental health was at an all-time low. I was also completely confused as to why I hadn’t been dropped by any of my reps. I sucked at my job—why didn’t they know that? On the other hand, if I hadn’t sucked at my job, it would have just led to my worst nightmare: having to direct more commercials.

The day I left the Sofia-Wes production company, I walked out onto Hollywood Boulevard with tears streaming down my face. I was literally walking down the Boulevard of Broken Dreams like a goddamn cliché, something I was sure would never happen to me after the success of my viral videos. “This time will be different,” I’d believed. How naïve.

There are no promises of huge paychecks anymore, but there are no disappointments when they don’t come, either.

Leaving commercials meant giving up my visa to live in Los Angeles, which broke my heart even more. But I was willing to give it all up to never have to bullshit my way through another conference call.

I’ve been humbled. I’m not at the cool kids’ table anymore. But the work I do for money now is work that I do well and that I get praised for. I leave my job behind at the end of the day, and I have time to work on my personal film projects. When I travel, it’s to see friends and loves and family, not to sit in a hotel room alone, dreading an exhausting client dinner. There are no promises of huge paychecks anymore, but there are no disappointments when they don’t come, either. Without commercials, I may never be able to buy a house, but at least I’ll be alive to pay rent.

So, for those of you who covet being a commercial director, I’ve opened up a spot for you. May you do better things with it than I did.