As Mayor of New York City, Rudy Giuliani became synonymous with his attack on nightlife—including queer clubs and bars—launching a siege on its counter-cultural spirit in the process. In this period, photographer JJ Jimenez was coming of age and coming into her queerness, making friends and lovers to fight back with hedonism and fun. She speaks to Megan Wallace about rediscovering her archive from those crucial years: a visual catalog of what being a young, queer New Yorker looked like two decades ago.

When the artist JJ Jimenez moved from the US to Australia with her wife in 2020, this radical life-change coincided with the global pandemic—a period of tumult and isolation that led her to look back to her archives. Taking the moment of collective stasis to comb through years’ worth of her personal photos, she came to understand that what she initially thought were just candid shots were something more, the bones of a compelling visual diary of the late 90s, 2000s and early 2010s of her coming-of-age in the queer counterculture of New York City. Sifting through these ephemeral photos, Jimenez was confronted with the bold immediacy of her work behind the lens. “I realized these are not just snapshots—these are something that I feel an emotional connection with,” she explains. “I put the images together and began looking at them. It’s then that I started to explore themes of memory, identity and queerness.”

I was documenting people and spaces that often get overlooked… quiet moments of intimacy and unexpected run-ins with strangers.

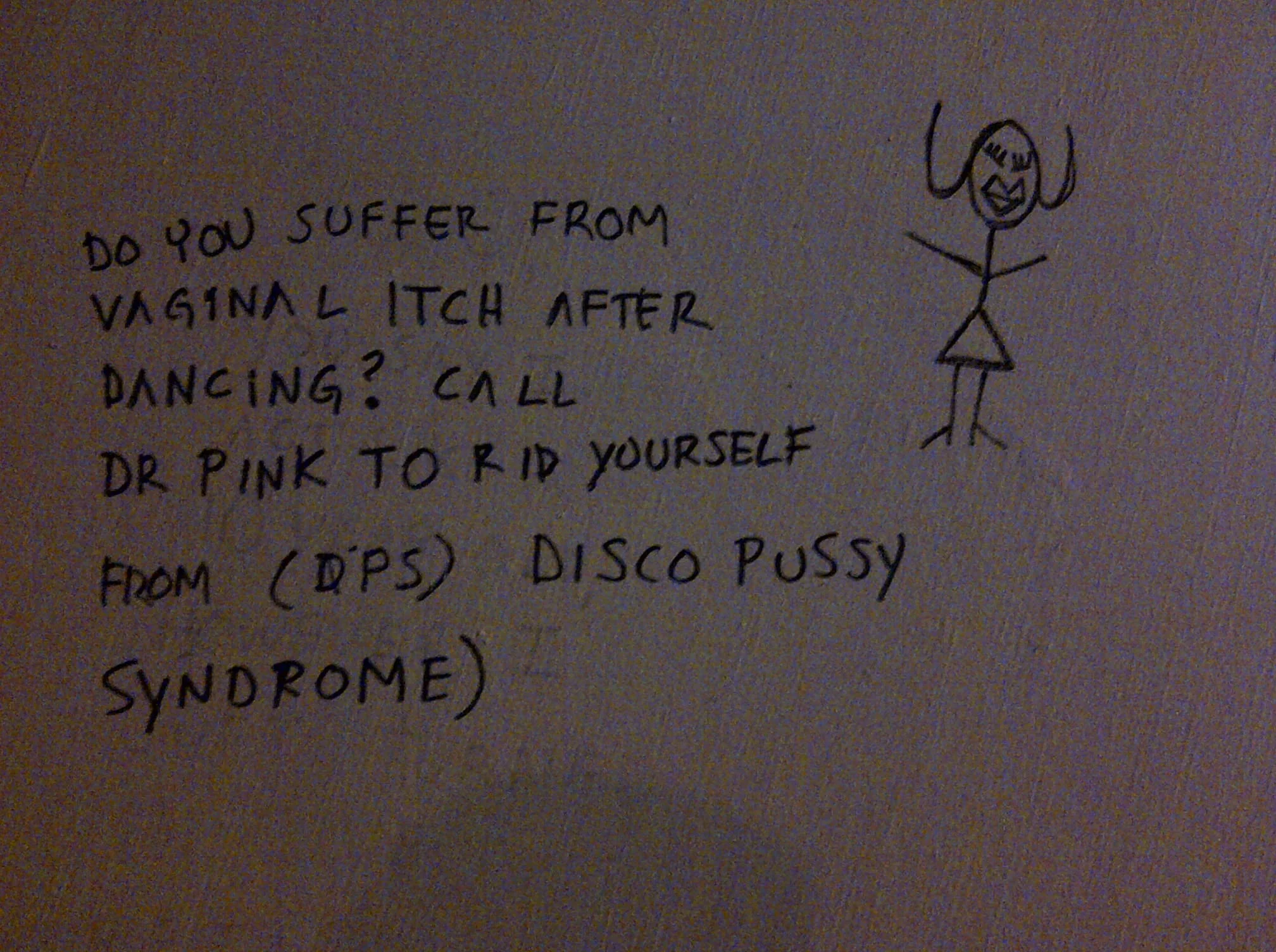

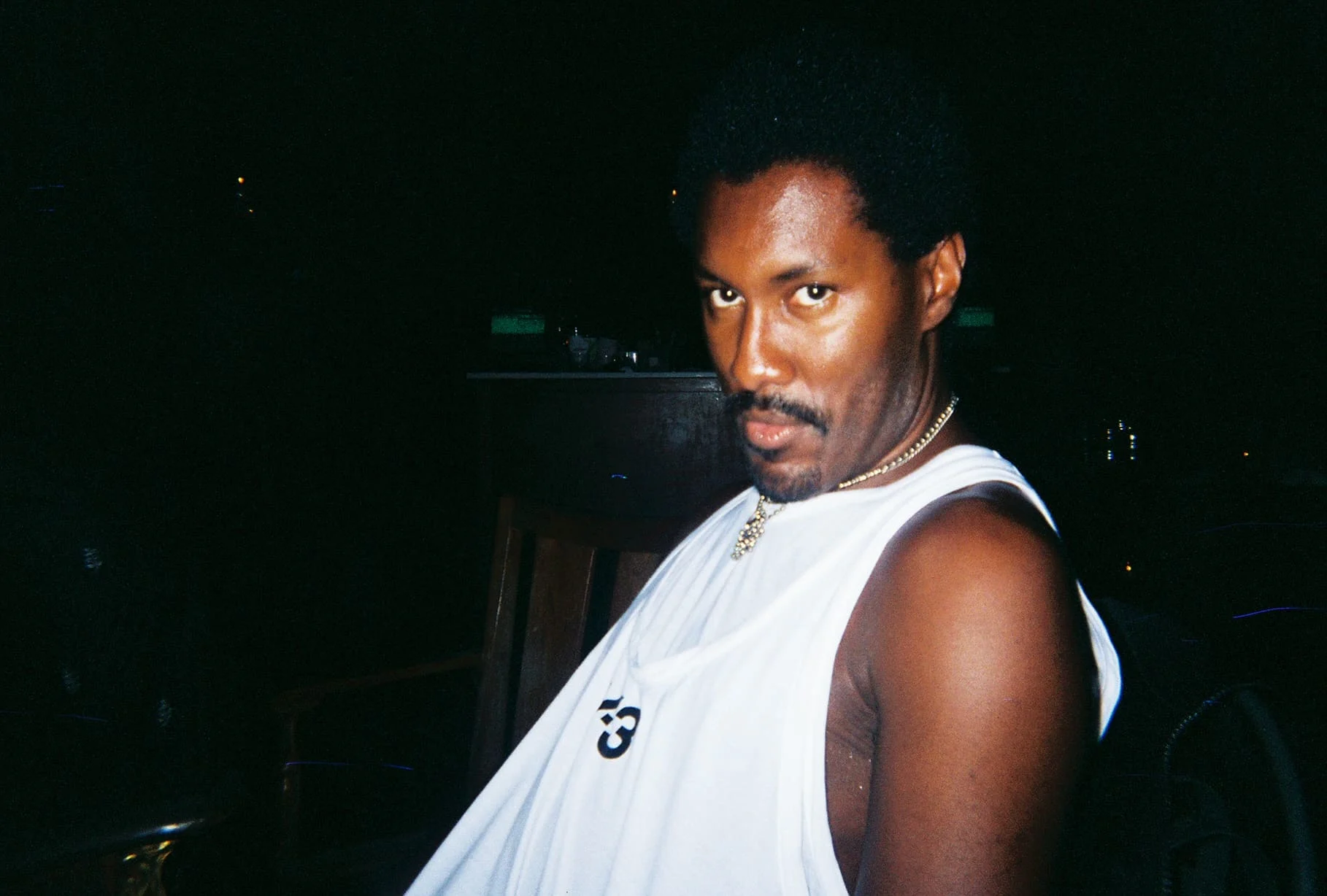

The resulting body of work is “Disco Pussy Syndrome”: a self-published zine that collates sweaty, serendipitous moments from these heady days in the city—candid exchanges during long hours partying, flashes of hedonistic nakedness on the beach, flowers in audaciously full bloom, and tongue-in-cheek slogans snapped on billboards, tees, bathroom graffiti and even discarded coffee cups. For Jimenez, this project is an encapsulation of the voracious connections of nightlife, where a fleeting encounter on a dancefloor can lead to friendship, love, or even just moments of tenderness in the early morning light. “Most of the photography was documenting people and spaces that often get overlooked, especially scenes from nightlife,” she says. “You know, quiet moments of intimacy and unexpected run-ins with strangers.”

This is aptly summed up by the zine’s name, which comes from a scribbled line on a bathroom door which is included within the final collection of images. “It totally grabs you,” Jimenez says of the zine’s direct and compelling title. “If I saw a book or something called ‘Disco Pussy Syndrome,’ I would totally pick it up. It’s tongue-in-cheek but, when you think about it, it represents disco, rooted in queer nightlife, pussy for sexuality, and then syndrome – something that infects you, that lingers, something that stays with you and transforms you.”

Indeed, the period documented within these images is one which was highly influential to Jimenez’s self-development—allowing the images to take on an almost autobiographical quality. “Most of these pictures were taken during the late 1990s and early 2000s, that era kind of shaped me,” she says. “It’s when I met my wife, it’s when I was vacationing with a group of friends in Fire Island. Those moments, those friends, are still really dear to me. This is why, when I look back at these images, they’re so emotional. They bring back certain places or certain moments, that energy, you know, just brings back these wonderful memories.”

During trips to queer clubs like The Clit Club, Jimenez would whip out whatever camera she had on her in the moment—often her point-and-shoot Yashica T4 or, even her BlackBerry phone camera—to capture the energetic, effervescent scenes unfolding around her. From nightlife legends like Amanda Lepore in the Meatpacking District, to the intertwined limbs and mouths of newly formed couples, the resulting shots position the viewer at the beating heart of counterculture. “I feel like the pictures might look voyeuristic, but they’re not,” she explains. “I was a part of the gang, I was living it. I was there hanging out with my friends and just documenting what was happening. Nothing was planned, everything was intuitive.”

Fire Island is the most magical place on Earth for anyone that wants to be themselves, that wants to be free.

The years which make up the bulk of the project coincided with a period of greater queer visibility and social acceptance but, in New York City, they overlapped with Rudy Giuliani’s turn as the city’s mayor and subsequent attack on the city’s nightlife and sex industries. During his 1994 to 2001 run, he resurrected a Prohibition-era cabaret law which ruled that establishments would have to have a specific license if more than three punters were dancing at any one time, and also continued to push the peep shows and porn theaters out of Times Square.

Looking back, Jimenez notes that, in his wake, the queer community came together across identity distinctions, to support their clubs and bars, pushing back against the efforts to sanitize and silence their scene. “Post-Giuliani, when people realized that all these queer spaces were being closed down, people started to get together more and unite,” she recalls. “There was a big lesbian bar in New York called The Cubby Hole. At the beginning, it was very much a lesbian scene and then, after a couple of years, it started being frequented by more gay men.”

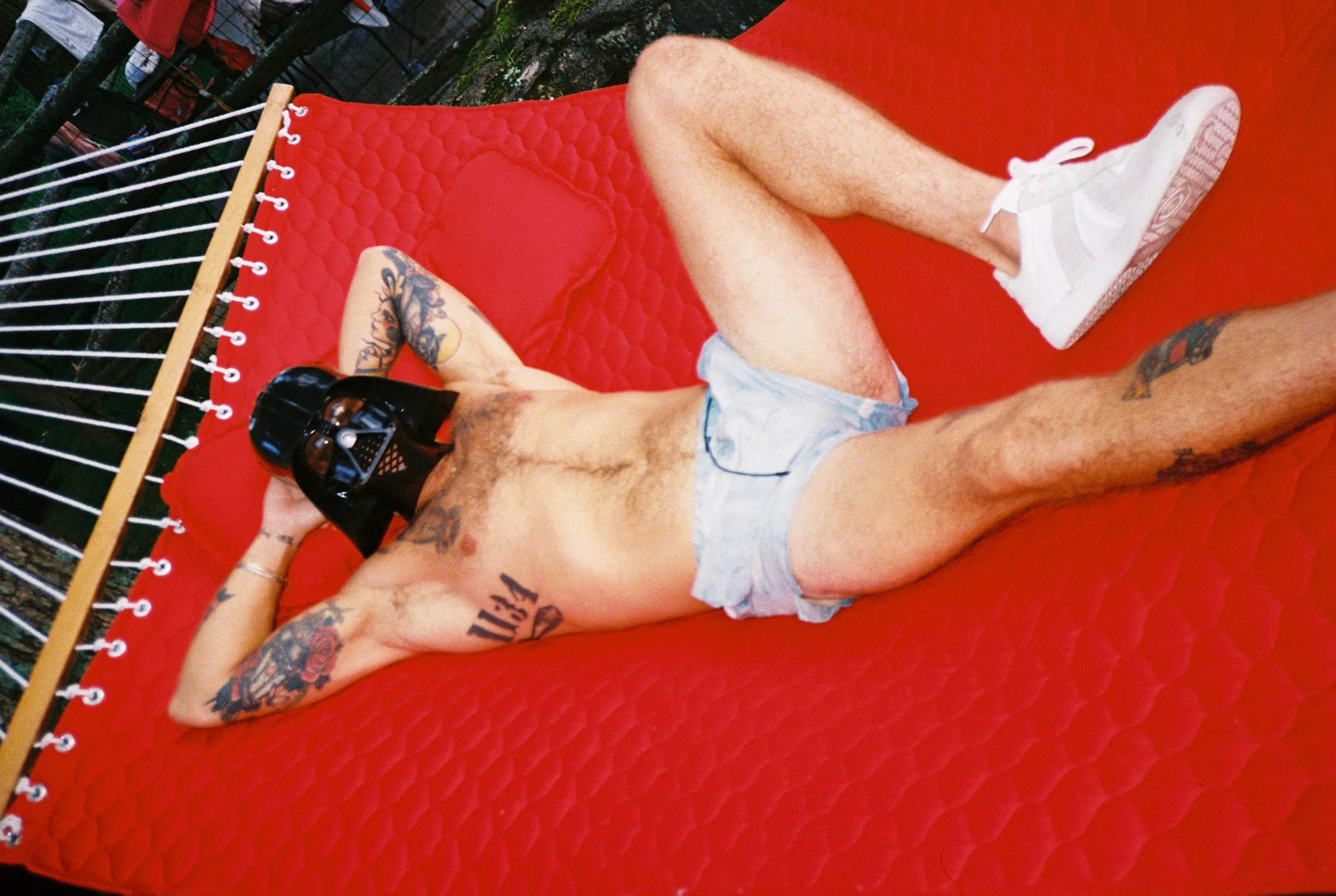

However, not all the images in the series take place in the city: some of the project’s most evocative shots take place against the waterfronts and expansive skylines of Coney Island and Fire Island, in greater New York. In particular, Jimenez has positive memories of Fire Island, a notoriously pro-LGBTQ+ vacation spot. “It’s sort of anything goes,” she adds. “It’s the most magical place on Earth for anyone that wants to be themselves, that wants to be free.” It’s here that queer city dwellers are able to get a much-needed dose of nature—a meeting of disparate worlds summed up by one particularly arresting image of a deer, stumbled onto the beach amid scantily clad sunbathers. “I was just with my ex-girlfriend and all of a sudden there was a deer, my first impulse was just to grab a camera,” she says.

The uncanny nature of this image echoes the dream-like quality of some of the more surreal photos included in the project, as well as the shots which seem to capture the post-night-out delirium of an after party or of walking home while commuters head to their day jobs. It’s a texture which adds a depth and whimsy, and is something which she attributes to her artistic influences. “I think the dreaminess comes from some of the work that inspires me—photographers like Corinne Day. There’s a lot of fashion sensibility injected into some of the images because I've done a lot of fashion work,” she says. “Other inspirations are photographers like Wolfgang Tillmans, Juergen Teller and Nan Goldin.”

Ultimately, Jimenez feels like the images in “Disco Pussy Syndrome” shouldn’t just feel like a febrile dream or a rosy-hued look back to years gone by. Instead, she hopes that this candid look to a recent past—one filled with equal parts hedonism and solidarity—can help inspire a new generation of queer people growing up during the cultural regression of Trump’s America. “It’s not like I wanted it to be nostalgic, I didn’t want to relive these moments,” she says. “With everything that’s happening now, I want people to remember not just that queer people are marginalized, but the good times—the night times with our friends and chosen families who we celebrated with. I think that’s really important to remember and hold onto.”