Artist Dozie Kanu was raised in Houston, Texas. His varied cultural experiences at home and at school helped to shape his worldview and artistic practice. He designs chairs not for functionality, but as a method of communicating ideas about space, exclusion, and absence, particularly with regards to the Black experience. His work was selected by Solange Knowles as part of her guest curator series on WePresent. Here, he speaks to writer and curator Ferren Gipson about his artistic journey thus far and the ideas present in his work.

“A believer in the life force of objects, Dozie Kanu activates an incarnation through his sculptures. I admire his ability to create spiritual and kinetic energy by turning ideas into artful assemblages. As a fellow Houston native, I really connect to the thread of geographic lineage that he magnifies through his work, and appreciate his ability to create innovation through tactility and material.”

– Solange Knowles

Falling in love with film

There should be a word for artists whose work occupies the liminal space between art and design, as Dozie Kanu’s does. He refers to his three-dimensional work as “objects,” and his practice spans sculpture, installations, production design and more. With aspirations to combine his talents to create films, Kanu seems set to become a multidisciplinary powerhouse.

Kanu was born and raised in Houston, Texas. His parents emigrated to America from Nigeria before he was born, and he says his varied cultural experiences at home and school helped to shape his worldview.

As a kid, he tried his hand at every sport, but eventually realized he was just more of a creative kid. At 15, he was gifted a camera and became the go-to videographer for all family occasions. By the time he was 16, Kanu had his heart set on becoming a filmmaker. This decision was motivated by creative and practical reasons, as his parents preferred that he pursue stable career options.

“When your parents are working-class immigrants, it typically puts a lot of pressure on you to eventually take the reins of the family and be the one to lift the family out of poverty,” Kanu says. “I think I gravitated to filmmaking because it was a discipline that offered creativity that my parents could understand. There’s a huge Nollywood industry in Nigeria and it felt like there could be some acceptance from my parents by me taking that path.”

After high school, he moved to New York, where he completed an undergraduate in film at the School of Visual Arts. While there, he soon realized that he was at a financial disadvantage compared to some of his classmates who came from families who could help fund their projects. As he reconsidered ways of approaching his filmmaking practice, another student asked him to do the production design on one of their projects.

“I found enjoyment there because I felt like I still had some input on the visual nature of the films, and what ended up being in the frame was partially my vision,” Kanu explains.

I gravitated to filmmaking because it was a discipline that offered creativity that my parents could understand.

He established a reputation as a talented production designer, and more students began to come to him for work—he was even approached by filmmakers from other universities. The professors also took notice. Simona Migliotti, a set and production designer who has worked with the auteur Wes Anderson, took Kanu under her wing and helped him craft a bespoke production design emphasis for his degree.

“There was no actual production design major,” says Kanu. “Because of my interests and because she felt that I had some talent, she went to the heads of the film department and helped create a curriculum, which involved taking interior design classes, interior architecture classes, [and other] courses that film students usually weren’t allowed to take.”

An impactful entry to the art world

During his third year at school, Kanu’s family had an emergency that necessitated he find a job to contribute some financial support. He sent his resume to every interior design studio he could find and landed a position as a junior designer with a designer based in Chelsea. There, he gained experience creating mood boards, sourcing objects, and designing spaces, but more formatively, he began to frequent the nearby contemporary art galleries. Seeing shows helped him familiarize with the contemporary art world and led to a shift in the way he thought about his practice.

A show that I saw by Scott Burton at Kasmin Gallery in 2015 really cemented my belief that you could have an art practice that was adjacent to design, but not design.

“A show that I saw by Scott Burton at Kasmin Gallery in 2015, really cemented my belief that you could have an art practice that was adjacent to design, but not design,” says Kanu.

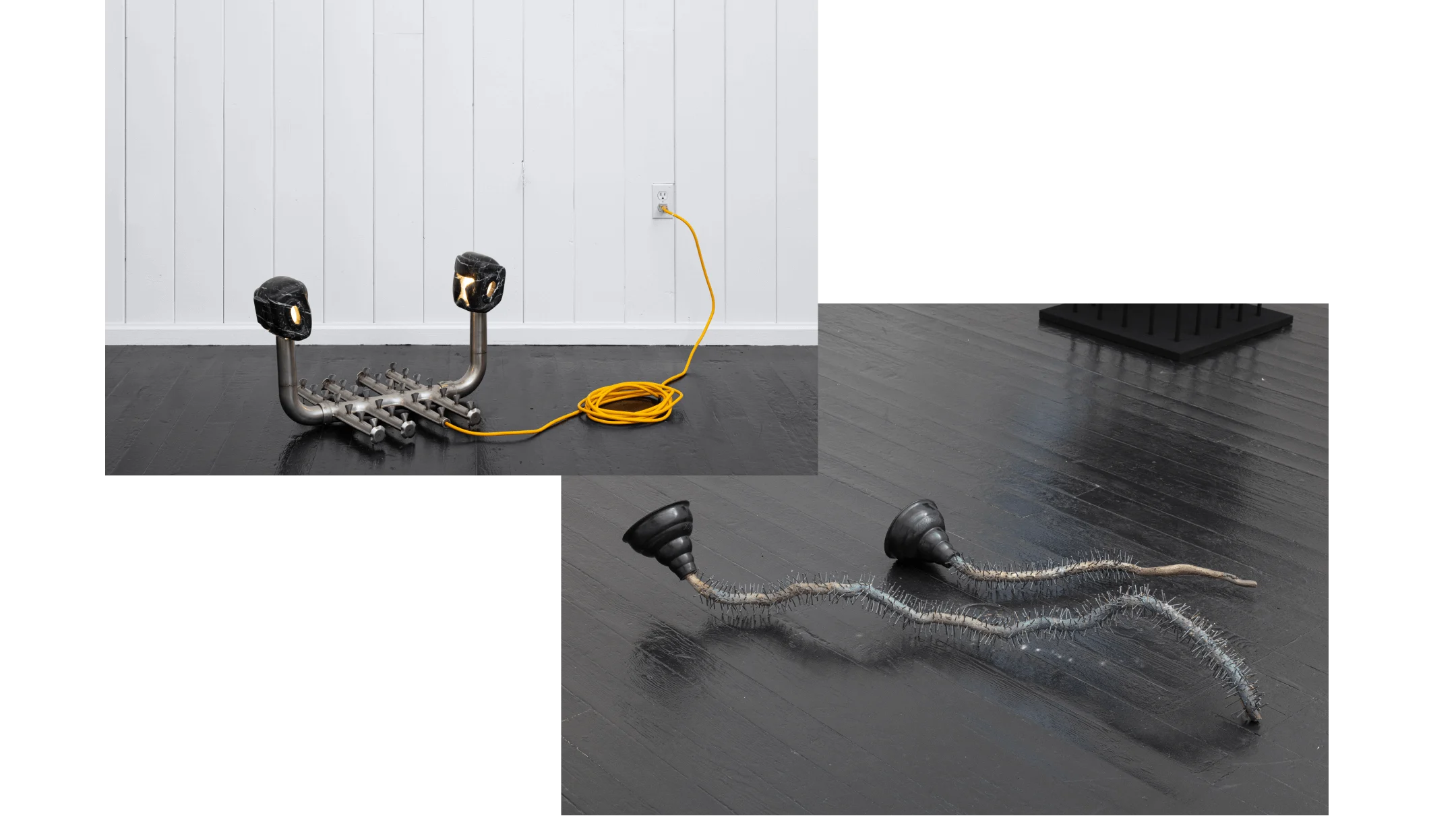

Newly invigorated, Kanu began to create his own sculptural objects. In 2016, he made “Teepee home (Pro Impact),” which was later exhibited at the Studio Museum in Harlem. In the piece, he arranged six extendable magnets into the form of a tepee. Blue boxing gloves, by the brand Pro Impact, sit at the base of each pole, as if punching into the ground. The work asserted his emergence on the art scene and, looking back, he feels he was “trying to will an existence into reality.”

That ambition started to materialize after a friend invited Kanu to participate in a group show, organized in a vacant space. Gallerists took notice of his work, and he was subsequently invited to exhibit at the “Midtown” show at Lever House alongside artists like Scott Burton, who had inspired him so much. Kanu created a bench made from purple concrete slab hovering over two wire wheels (also known as swangas or elbows). The inspiration for the work came from the Slab car culture in Houston.

“[Slab culture] emerged from the ghettos of the city, and to me, it made a lot of sense to take that position within my invitation to contribute to this group exhibition,” says Kanu. “I had the opportunity to align myself with a movement that was very much about the customization and the manipulation of property and material, which is complicated as a Black American, as an African American, based on the idea that we were once considered property.”

Taking a seat at the table

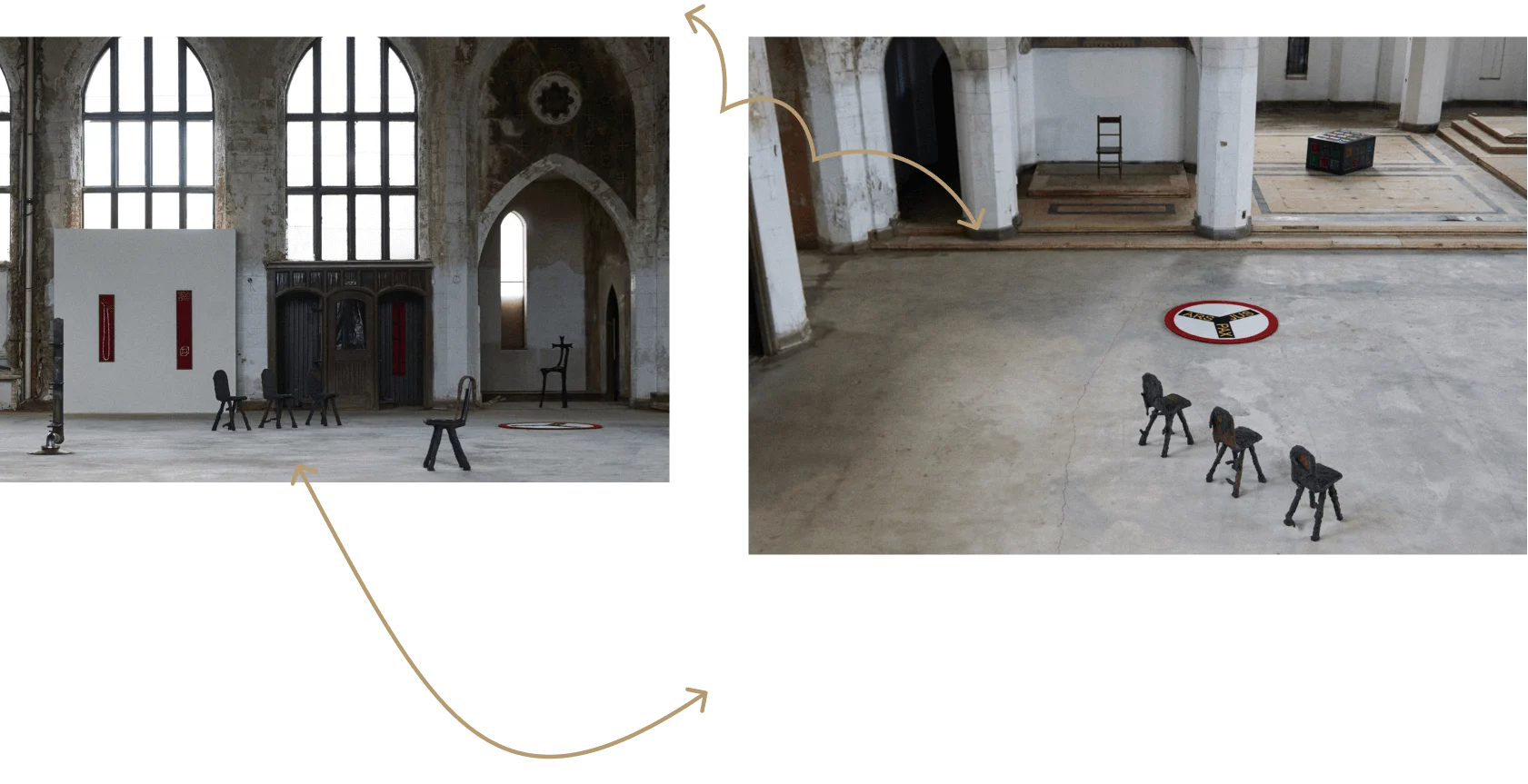

Among the varied sculptures Kanu creates, he often returns to chair forms and other allusions to seating in his work. If viewers only engage with these objects from a position of furniture design, however, they will miss the complex concepts at play in these objects.

“If you look at popular contemporary Black art, a lot of it is about the Black figure or the Black body being represented, and I saw the chair as this almost absence of a body, absence of a figure,” says Kanu. “I felt like it could be an alternative symbol for being included in a conversation that I felt excluded from. It’s interesting that Solange has an album titled ‘A Seat at the Table,’ because I saw my approach as alluding to that in a way.”

I saw the chair as this almost absence of a body, absence of a figure.

He’s made a series of chairs that allow him to tap into different issues and conversations. For a 2019 solo exhibition at Studio Museum, Kano showed “Chair [ix] (for Babies),” which is a tall chair similar in form to those used for infants. In creating this work, he explained that he was thinking about the idea of play and the freedom children have to experiment and explore. Other chairs, such as “Chair [v] (Electric Chair),” tackle heavier subjects. The deconstructed electric chair, made from the luxury material of marble, conjures thoughts of America’s privately-owned prison systems, which profit off the lives of Black and Brown people.

An expanding practice

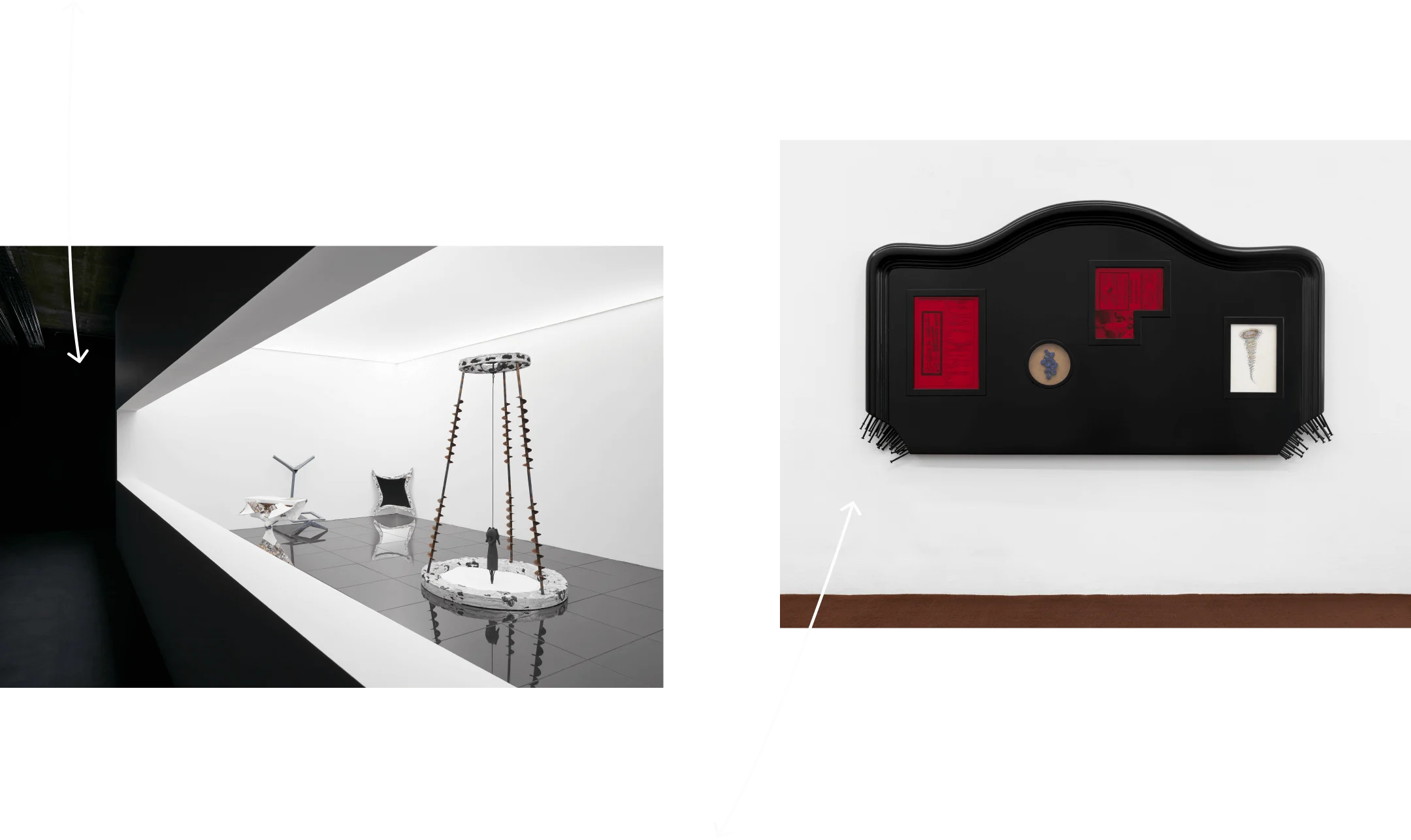

After a period traveling, Kanu established a studio in Portugal and now works between there and New York. With cheaper living costs and space to think, he’s expanding the scale of his work and drawing on his roots in production design for recent work. In 2019, he created an installation for the London exhibition “Transformer: A Rebirth of Wonder,” where he was able to exercise creative control over everything from floor to ceiling. The work has a futuristic feeling, as if looking into a setting on a spaceship. Interestingly, working on the installation led Kanu to reflect on Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” and the vision the director was able to execute by having few financial constraints. Kanu also thought about freedom and experimentation that went into Hype Williams’ film “Belly,” which he celebrates for being “unapologetically Black.”

“I guess that installation is a little bit like the debris of the thoughts around those two films,” says Kanu.

I’m using all of the resources that I have readily available at my disposal to create the things that I want to make

Kanu has his eyes set on film projects next, and he is keen to create worlds within cinema in addition to his sculptural practice. He sees his work to date as offering a glimpse of the full potential he can unleash with the right resources.

“I’m using all of the resources that I have readily available at my disposal to create the things that I want to make,” says Kanu. “The more that I have at my disposal, I think the [more] important or effective the work will be.”