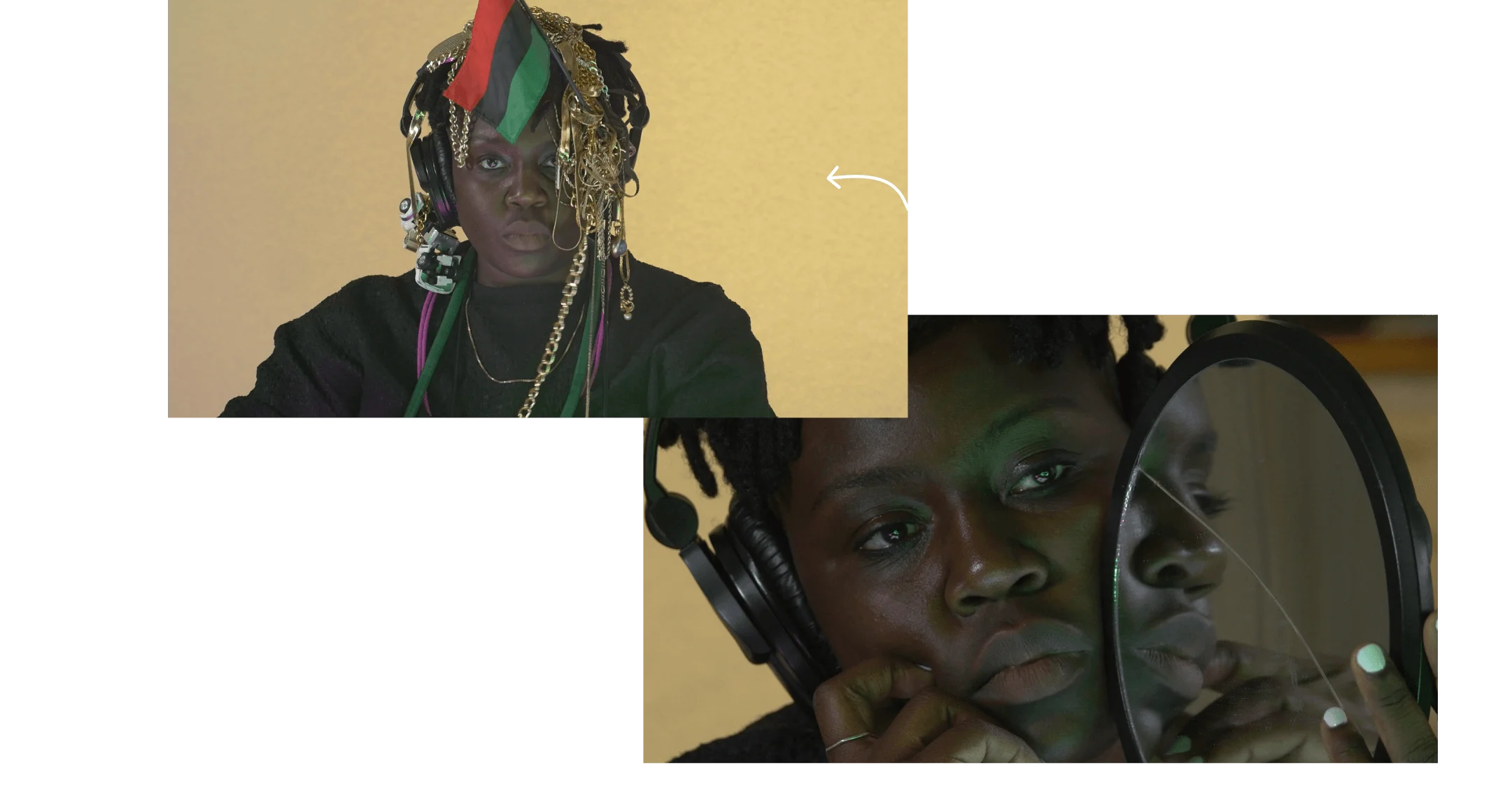

Houston-based artist Autumn Knight had a turbulent start to her arts education, but soon found herself on the path to exploring new ways of working in theater. Now, trained in a number of theatrical practices such as choreography, writing, improvisation, and acting, she observes the world around her and uses her toolset to communicate ideas of Blackness and identity to the world. Her work was selected by Solange Knowles as part of her guest curator series on WePresent. Here, she speaks to writer and art historian Ferren Gipson about what she’s trying to get across.

“Autumn Knight’s artistry combines performance and visual art to overlap subjects, soundscapes and settings in the contemplation of identity; specifically with regards to race, gender and authority. I’m in awe of the way she marries theater, raw expression, psychology, and choreography to evoke feelings of Black feminine interiority.

The consciousness personified in Autumn’s performance and video work engages the audience with presentations that rely on truth, humor and compassion to defy the confines of traditional art. It’s exciting to observe her connection to the body, psyche and physical space alongside media in an artistic practice that questions both the familiar and unknown.”

– Solange Knowles

The first spark

Autumn Knight has a special affinity for phoenixes. Her connection to these mythical birds traces back to a fire that destroyed her family’s home when she was in the second grade. Over the course of her life, she’s experienced several moments when she has had to remake herself and—literally and figuratively—emerge from the ashes of near-defeat. Today, her artistic practice is strengthened by the cumulative effect of these challenges, and she looks forward to more changes as she sets her sights on doing more collaborations and exploring cinematic projects.

Knight grew up in the Third Ward area of Houston, Texas. Her mother worked for the school district and placed heavy emphasis on the importance of education. Knight jokes that even after her house burned down, she still had to go to school the next day.

I want people to understand the complexity of how humor can be used, and the depths of it.

Beginning in elementary school, she attended an arts magnet school (a specialized public school), where she was able to explore music, dance, theater, and visual art. For high school, she attended the Kinder High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, which required an audition for entry. By this time, Knight had zeroed in on theater as her specialty. She describes the school as being similar to the movie “Fame,” with an environment filled with talented students who were serious about honing their craft. The expectation was that everyone would continue to pursue their careers at university level, and she did.

Back into the fire

The second fire Knight experienced (and mercifully the last actual blaze) occurred while she was studying at Dillard University in New Orleans, when she accidently set fire to her dorm room. She was subsequently kicked out of school for one year, but later was allowed to return to finish her degree in theater.

It took time for her to adjust to the school. In her younger years, she’d gone to a racially mixed school, in which they had mostly studied plays by writers like Tennessee Williams. Suddenly, as a new student at a historically Black university, her focus was being directed exclusively at Black playwrights.

I think culturally and artistically, it really made me center Blackness.

“I think that’s when I really fell in love with being Black and recognized the importance of centering Black art in the middle of your practice,” Knight says, speaking in Rome, where she is for the Rome Prize. “Going to an HBCU is such an eye-opening experience because everybody’s Black… and we’re all studying different things. I think culturally and artistically, it really made me center Blackness.”

In 2006, a few years after finishing her undergraduate programme, Knight had a two-year fellowship with the Theater Communications Group in Houston. During this period, she developed a series of small residencies at charitable institutions, including AIDS Foundation and the queer youth group Hatch, where she conducted sessions doing performance exercises with people experiencing difficult periods in their lives.

Around this same time, Knight was thinking through her options for graduate school. A professor recommended that she consider studying drama therapy. This field seemed to resonate with the work she was already doing at the time, and she was soon accepted into New York University’s MA programme.

Fanning the flames

Drama Therapy was not what Knight expected. She thought she would still be fully immersed in her acting practice, but was disappointed to discover that theater was not a major component of her studies. Instead, she spent time doing internships and seeing therapy clients, which commanded an immense amount of emotional labor.

“It’s basically a creative arts therapy, like dance and movement therapy and music therapy,” Knight explains. “[Drama therapy] employs performance, theater, play, and acting, and methodologies related to theater. Those methods are employed in treatment.”

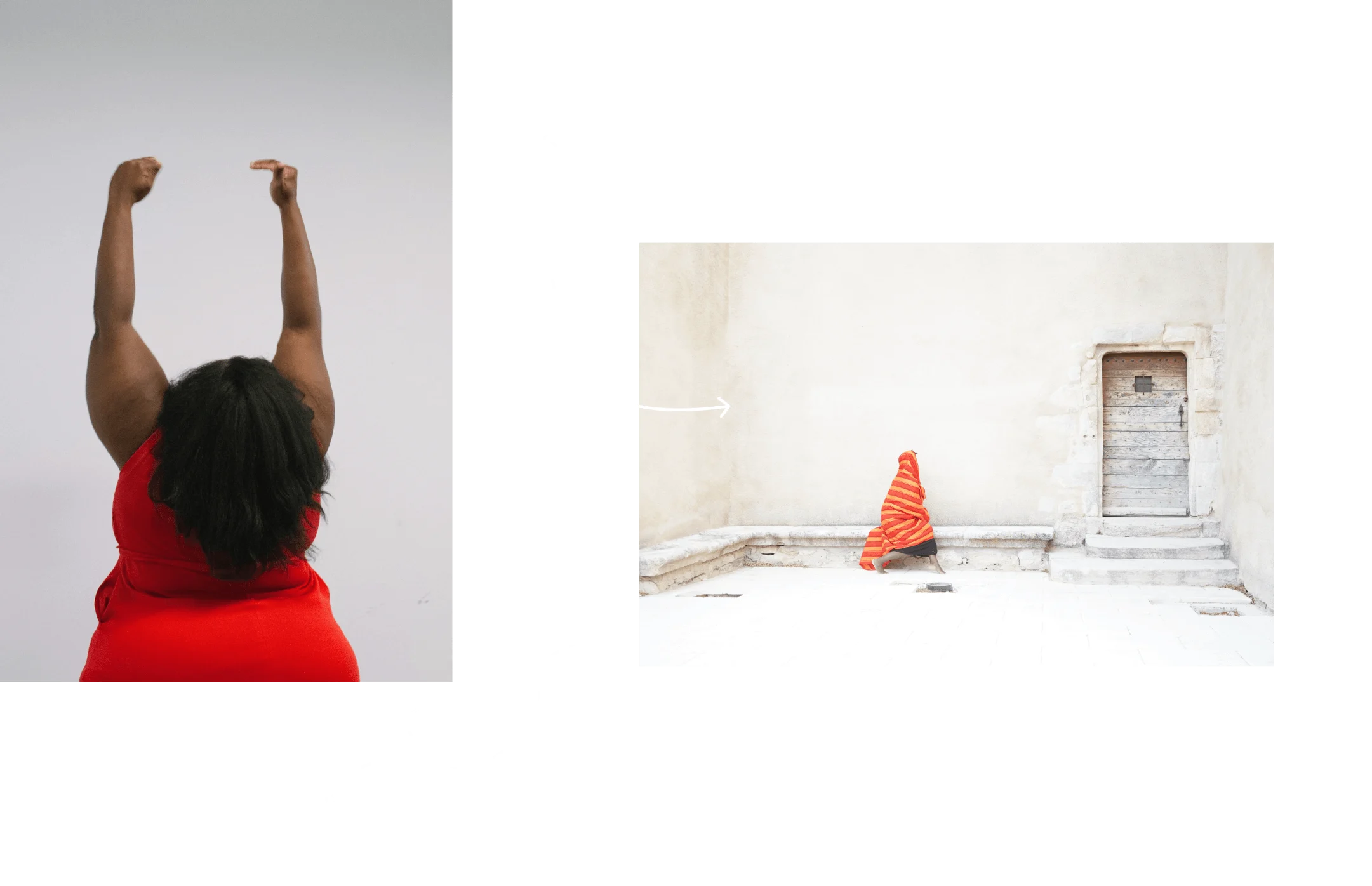

After completing the MA and returning to Houston in 2012, Knight had an epiphany regarding the path she wanted to follow in her career. She was working on a project for the Houston non-profit arts initiative, Project Row Houses, developing 10 distinct performance pieces over six months while acting in a play at the same time. There was so much she enjoyed about being an actress and working as part of an ensemble, but in comparing it with her performance art works, she was frustrated by the lack of control she had over the play’s more aesthetic components.

“I didn’t have the autonomy that I needed to be an artist,” she says. “The thing that I actually like to do is do performance and live-ness, which is what theater is, but in another permutation is a happening, an event, a moment, that you’re constructing.”

It’s like sifting for gold.

For the performances created for Project Row House, Knight drew on a variety of lived and observed experiences. She choreographed one dance after seeing a heroin addict walking around The Bottoms area of Third Ward. She noted the sad but intriguing way they nodded their head as they moved and imagined a reality where that person had aspired to be a dancer prior to using drugs.

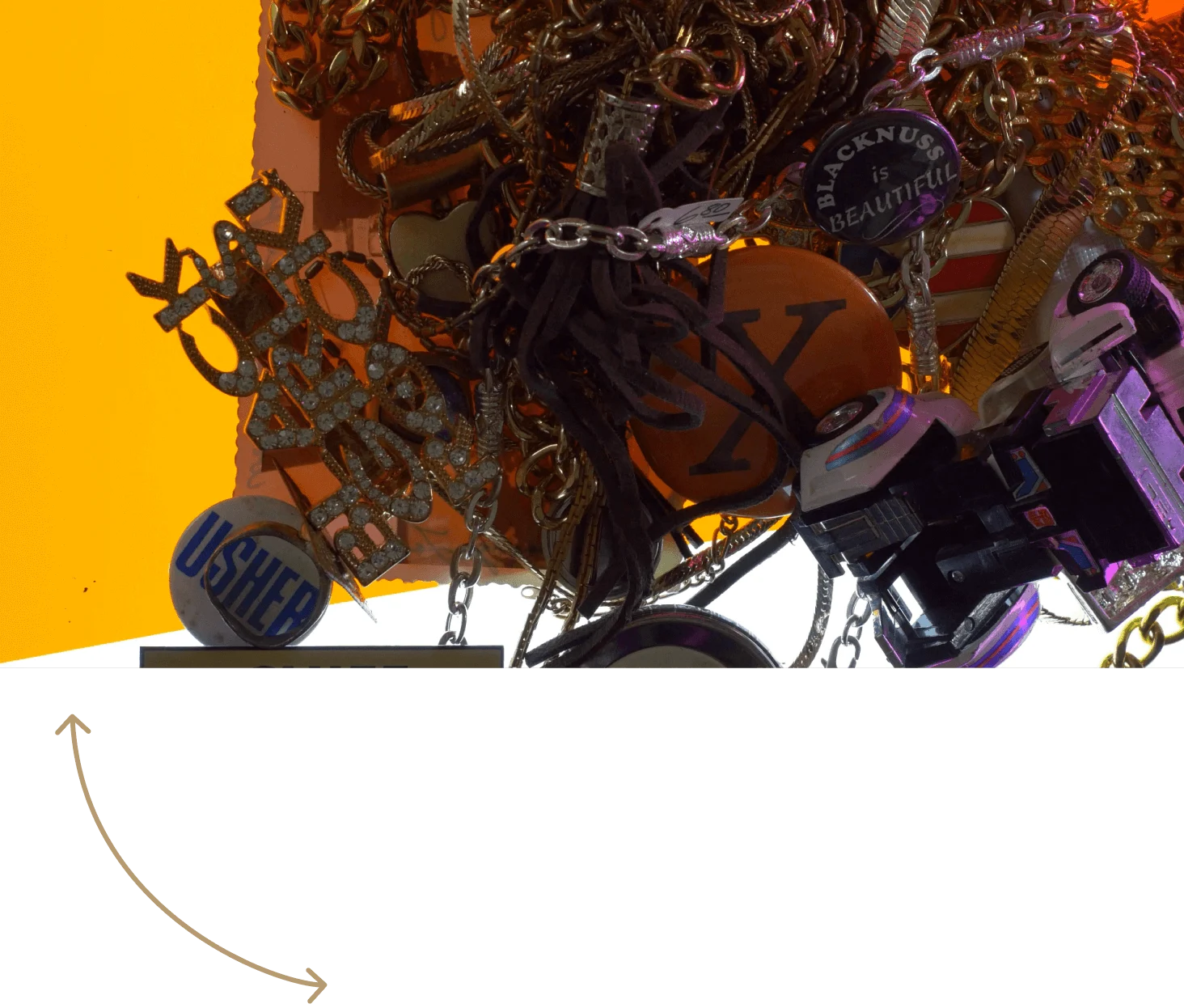

In another piece titled “Roach Dance,” Knight dressed in a beautiful gown and danced around as she slowly transformed herself into the maligned insect. Through works like these, she is able to plumb complex and difficult emotions. “That was based on a poem by Lucille Clifton, about her and her mother killing these roaches together in the kitchen,” Knight explains. “I grew up with roaches, so they appear in my work quite a bit. I think it’s about poverty and shame, and things I didn’t understand and still try to understand, [and also] the way Black people live in interior spaces and carry that out to the world, and have to hide it, or exaggerate it just to survive.”

Blazing a trail

In 2016, Knight did a residency at Studio Museum in New York that saw her combine her skills of improvisation with her therapy training. She developed her ongoing “Sanity TV” series, in which she assumes the role of a fictional talk show host and the audience become her guests. In this work, we see Knight’s humor and love of live audience engagement come to the fore as she follows abstract lines of questioning with random interviewees.

“Based on how they looked, I started making up things about them. I didn’t actually want to interview these people—I just wanted to use them as a space of projection,” Knight explains. “I’m not here to convince [the audience] to be sane or insane. I’m not here to convince you to do that. I’m here to point to things.”

This process of asking questions and “pointing to things” is a definite call back to therapy practices, but the framework of an improvised talk show with questions that aren’t necessarily rooted in fact renders the experience slightly surreal. Both of these qualities are encapsulated in the motto for the talk show, which explains it “doesn’t promote sanity or insanity.”

The audience is an important component of Knight’s work, even when they aren’t physically present. In the midst of the pandemic in 2020, she did a residency in New York at the experimental art institution The Kitchen, which meant she had to get creative about how to establish an audience connection. Sh e used live streaming to maintain a feeling of urgency in her performance as she filmed herself moving about the building. The visuals were overlaid with audio she would record that same day.

“Because I knew that one person might be watching through this live stream, I knew that I had an audience,” she says. “All of the audio is improvised. I would basically sit in a room every day and record these monologues that I would make up on the spot. It’s still the same components [of a live performance] but placed in different configurations.”

In her work, Knight works as a facilitator, presenting different objects and concepts to the viewer and allowing individual meanings to form for each person. In this way, she says her works are “almost like a Rorschach Test.” This approach may sound serious, but humor has always been a key element of her work, leavening the emotional aspects.

I’m not here to convince [the audience] to be sane or insane.

“I want people to understand the complexity of how humor can be used, and the depths of it. [There is] muck that you have to sift through to arrive at humor, and things that you have to rearrange and tease apart to arise and arrive to a place of humor—it’s like sifting for gold,” says Knight. “I’ve done all this sifting for you as a person, as an artist. Now I’m pulling out this thing that I can show you in a way that is digestible, in a way that is bittersweet, but it’s still sweet.”