Inspired by a trip to Brazil, where she saw different religions represented together in harmony, Victoria Ruiz’s latest photography series is a celebration of the Afro-diasporic religions of the Americas and the way they view nature as sacred, as something that must be protected at all costs. She tells Emily Steer about the process of making each of the vibrant costumes her characters wear by hand, and the many saints and deities from a whole host of religions that influenced the project.

Victoria Ruiz’s photographs pulse with life. Dressed in handmade costumes, her characters jostle and embrace, their bodies overrun with flowers, birds or thousands of colorful spikes. The Venezuelan artist’s joyful series “Para Tú Altar: Las Fuerzas Divinas de la Naturaleza” (For Your Altar: The Divine Forces of Nature) is inspired by the power of the Afro-diasporic religions of the Americas and their protection of the natural world, and her own spiritual journey. “I normally start my projects questioning myself and where I am at that moment,” she says. When she began the project two years ago, Ruiz had recently traveled to Brazil and seen the inherent connection between faith and nature in a new way.

These images are portals into another dimension. It’s a connection with the gods.

Ruiz was born in Venezuela and fled to Miami with her family as a child. “I got to know Latin America because of the people in Miami,” she says, noting how richly diverse the community was in that part of the US. Nonetheless, she saw a prejudice towards spiritual expression that differed from Christian beliefs. “There is a preconception that it’s voodoo, a view which comes from racism.”

In Brazil, a country she now regularly visits, Ruiz was excited to find “centro espírita” buildings, where different faiths are represented together. “Jesus is there. Mohammad and Krishna. All these powerful figures from lots of religions,” she says. This open approach is one Ruiz embraces; the title of her series is devoid of any single doctrine. “There are influences of Catholicism, indigenous religions, Yoruba culture. It’s mixed together in one. We are all interconnected, there are so many different entities. I wanted to tell my story as I felt these forces were really guiding me.”

We’re given these gifts from the gods, and instead of being grateful, we take it all.

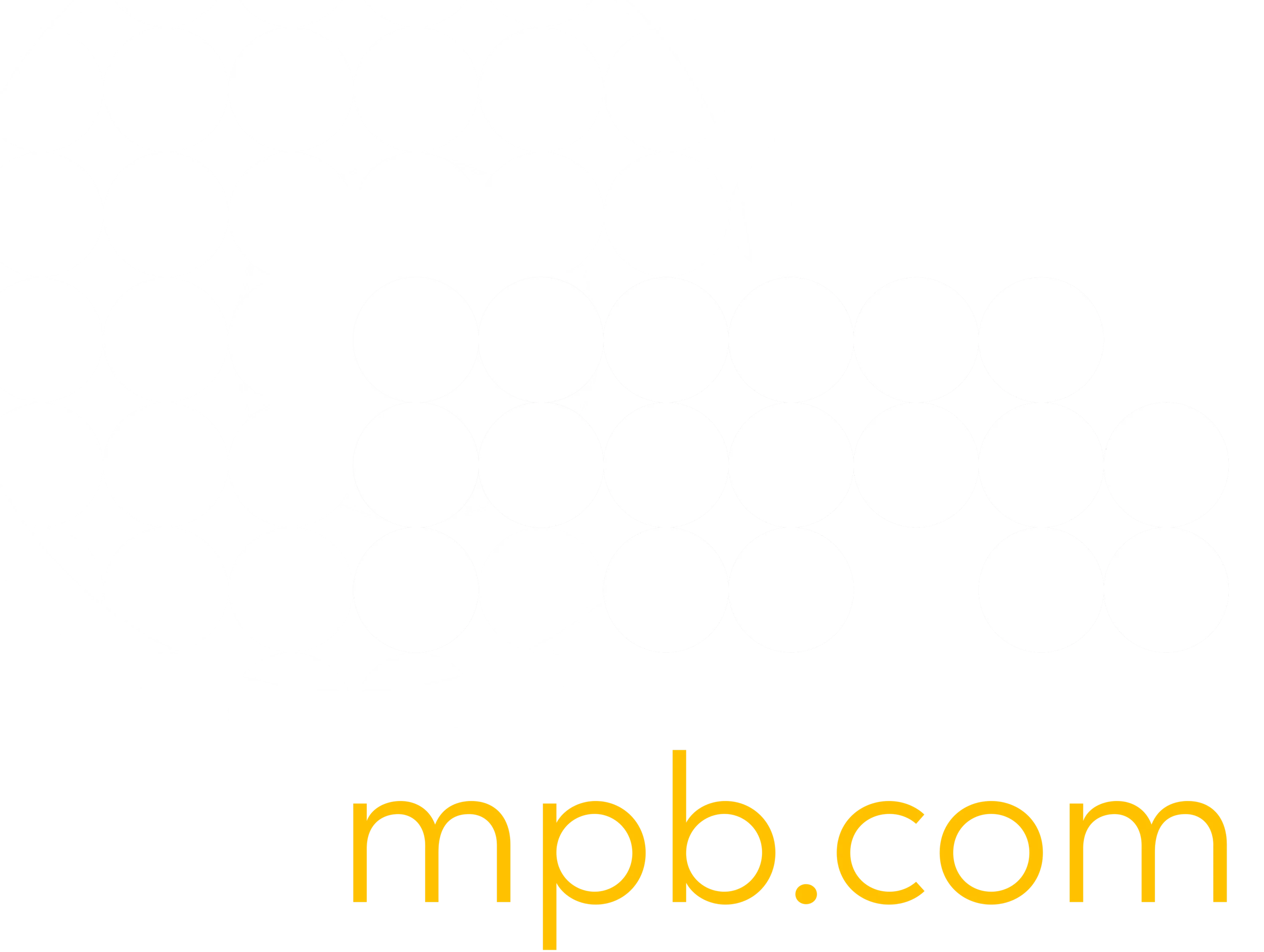

The first image she created was “Reflexión de Oshun, La Madre Que Me Protege (Reflection of Oshun, The Mother that Protects Me),” which features two figures standing side by side, covered head to toe in sunflowers. The work captures Ruiz’s connection with Oshun, a Yoruba deity who represents water, fertility and prosperity. The two figures mirror one another, encapsulating ideal love as a reflective, reciprocal act. The image also visualizes the artist connecting with forces of nature, asking for guidance.

Ruiz’s practice is all-encompassing. “I’m like an old seamstress lady,” she laughs, recounting the process of making each costume. Every image is the result of months of research and interviews with performers who will inhabit her characters; Ruiz looks for dancers who feel a connection with the images’ sacred intent. “Once I have these visual awakenings, if you can call it that, I start designing everything,” she says.

She creates PDF documents for each character, with bios containing information about their symbolic presence and the meanings of their costumes. The compositions and poses are drawn before the shoot begins. The photographs are made to a soundtrack of Celia Cruz’s album “Homenaje a Los Santos,” which had a profound influence on ceremonial Santero music. Each image represents an individual song, played on loop during the shoot, which creates a rhythmic effect for the performers. “They can really get into the characters,” she says. “These images are portals into another dimension. It’s a connection with the gods.”

Celia Cruz was a formative influence in Ruiz’s life. The singer was exiled from Cuba following the 1959 revolution and faced attacks on her religious beliefs and music. Ruiz notes a cultural kinship between Cuba and Venezuela. At Ruiz’s Cuban school in Miami, Cruz’s music played regularly in dance classes. “Celia is an icon in Cuba,” she says. “She is this empowered woman in a world of salsa. Amongst a load of men, she came in as the queen.” Ruiz sees parallels with her own life. She says that her generation in Venezuela “had our childhoods ripped away. I’m always trying to understand what it would have been like to live in my country. It’s about wanting to understand my connection and find what that little child wants to say.”

The thing that gives me joy is my belief. I want to believe in good and the power of nature.

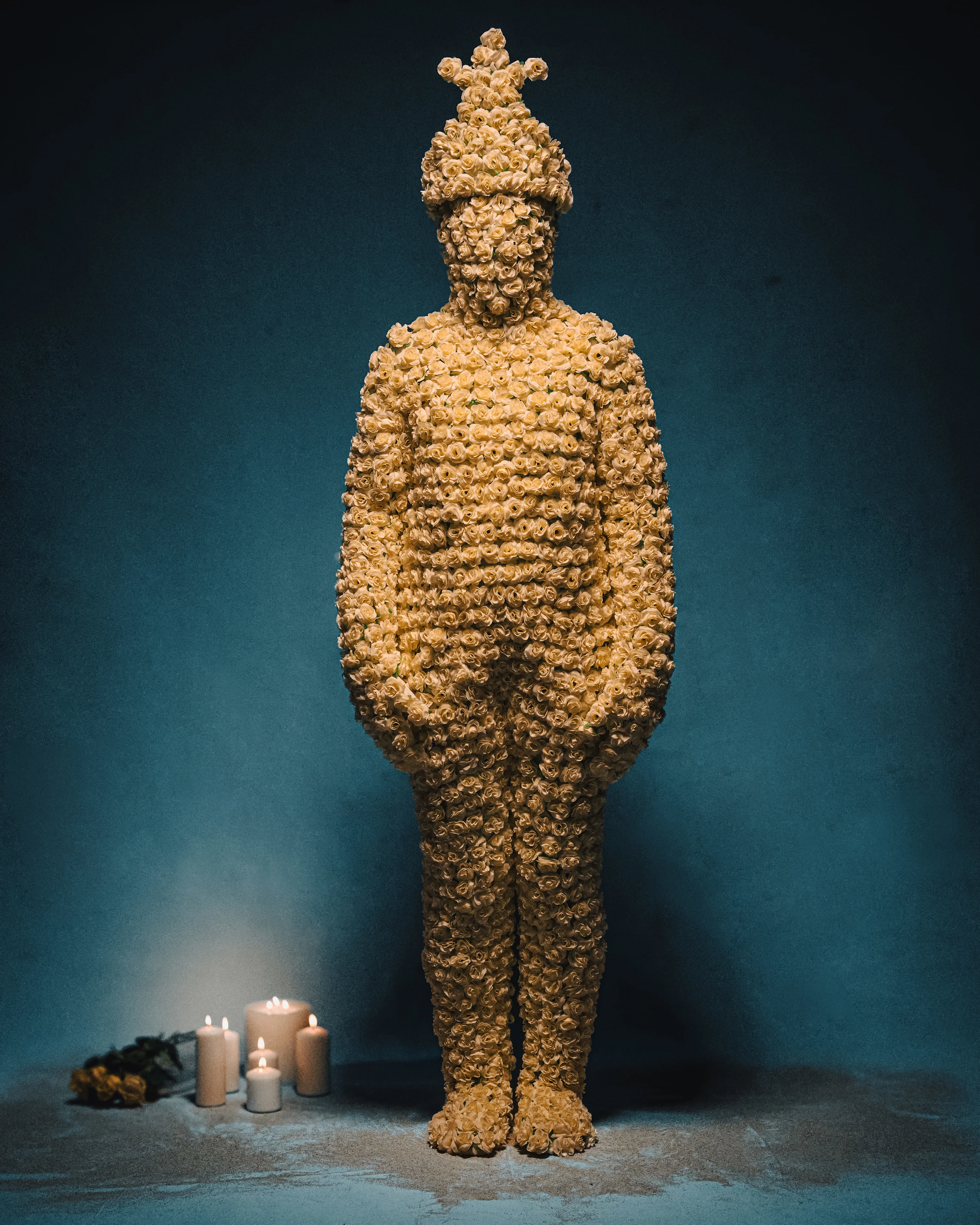

Balance is a theme that runs through many of her images. “Defiende Lo Sagrado, Por Favor (Defend What is Sacred, Please)” features the Yoruba divinity Ochosi precariously balanced on one foot as he aims to shoot an arrow, his body covered in colorful models of birds. Ruiz sees him as a protector of the natural world and highlights the importance of caretaker roles. She reflects on the mass destruction of parts of the Amazon rainforest in Venezuela, which has been severely damaged by the drug trade and regular fires. Indigenous communities have also slowly been pushed out and had resources taken away. “It’s meant to be sacred, but it’s been turned into a war zone,” she says. Nonetheless, she feels there is a force that protects it too, encapsulated by Ochosi.

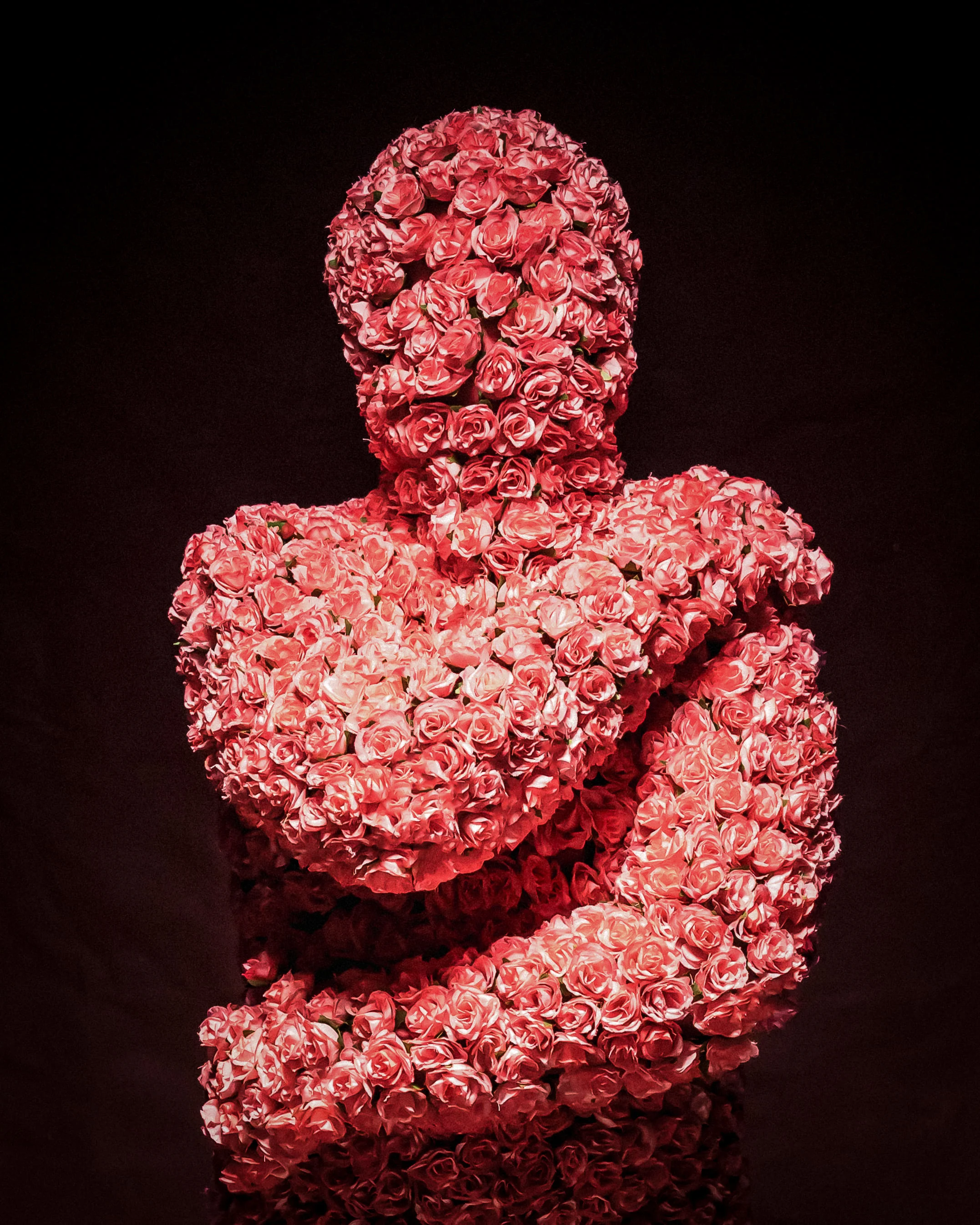

“La Dualidad de La Vida (The Duality of Life)” seems to show two figures in conflict; one red, one black, covered in flowers and shells. But they could also be holding one another up. The work depicts the complimentary forces of the deity Exú, who originated in Nigeria. “In western culture people think he is the devil, but in Yoruba religions devils don’t exist. Exú is just a balance of good and bad. Currently the world is so polarized. I think we need to find balance and understand what our goal is as an interconnected society.”

Ultimately, Ruiz sees Afro-diasporic faiths as an act of cultural resistance. “These religions see nature as sacred, which many humans are forgetting,” she says. “We [are given] these gifts from the gods, and instead of being grateful, we take it all.” She wants her work to show religion as a place for everyone, free from shame, punishment and hell. “The thing that gives me joy is my belief,” she says. “I want to believe in good and the power of nature.”

Creativity should be captured, and for a photographer, having the right equipment can be a crucial ingredient in doing so, allowing them to express themselves fully and do their subjects justice. With a dynamic pricing engine and a circular business model, MPB makes camera gear easily accessible so creatives of all kinds can share their stories. As two platforms that pride ourselves on enabling creativity to flourish the world over, this year, we’re curating some of our photography stories in partnership with MPB, the picture-perfect camera platform.