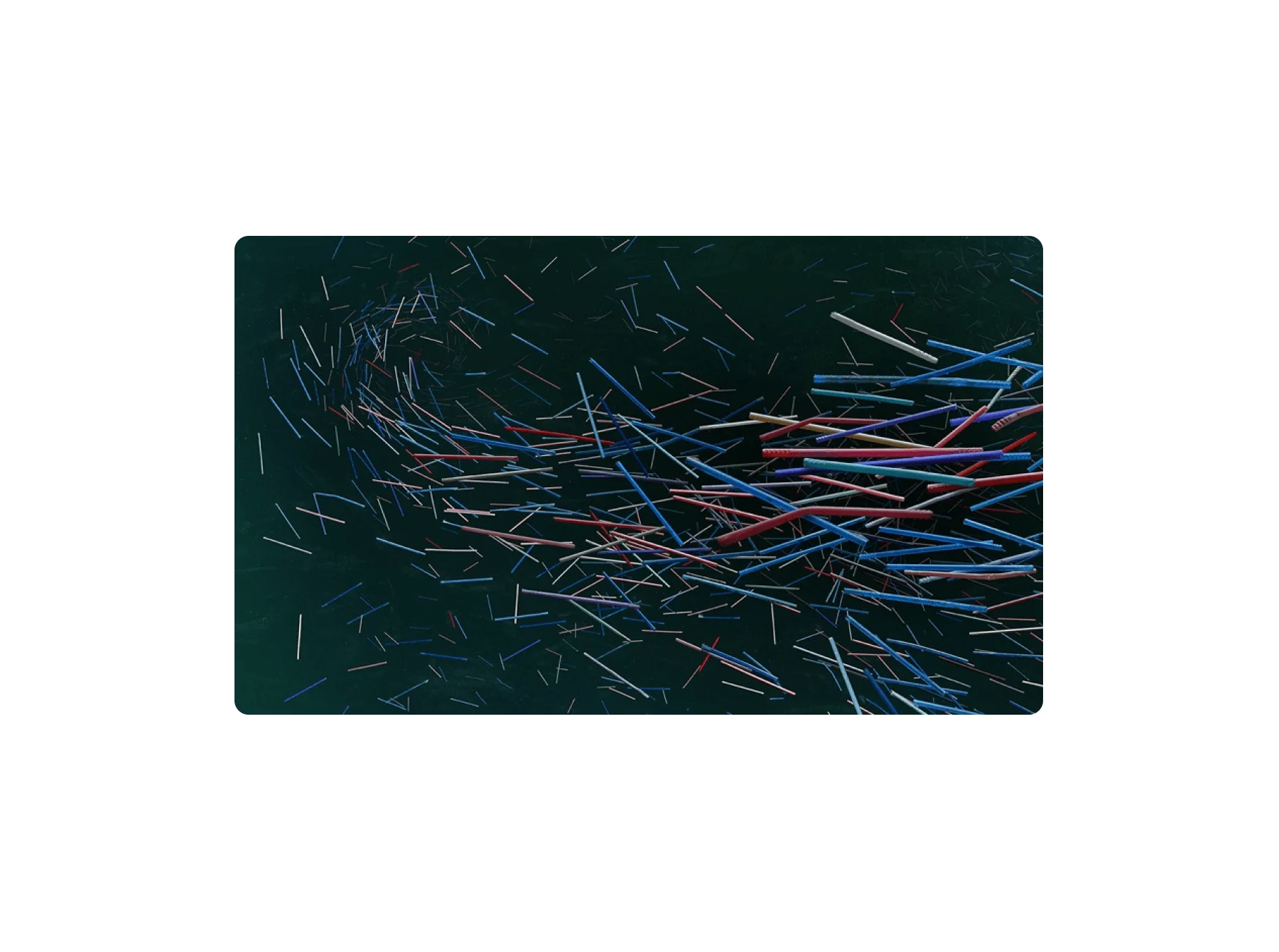

WeTransfer’s Union of Concerned Photographers uses the power of photography to underline the urgency of environmental concerns.

Huge amounts of species are dying out, lost forever from the natural world. In the past 25 years, the number of mammals, reptiles, amphibians, birds and fish in the world has dropped by a staggering 29%.

Ami Vitale is best-known for her work featuring animals – photographs of Kenyan rhinos, Indian elephants and Chinese pandas. But the stories she tells are not what they first seem. ”I don't even consider myself a wildlife photographer,” she explains.

“I'm really interested in the human condition and the human story. But I see that we live in this intricate web and we're all so deeply connected. Stories about nature and stories about people are one and the same. The deeper I get, the more that becomes evident to me.”

The journey to this personal epiphany – and her professional heights, as a contractor for National Geographic – was fascinatingly varied. It goes from the monotony of a business magazine in the Czech Republic to the world’s worst war zones. It reflects the changing way we’ve come to understand the world’s biggest problems. But it also speaks to the different factors that shape a creative career – hard work and good luck; a sense of time and place and the self-awareness to know when to make a change.

A shy teenager, Ami was first drawn to photography as a way round her social awkwardness. “I was incredibly gawky and afraid of the world, but the second I picked up this camera I had a reason to go out and talk to people,” she remembers. “I started telling myself different narratives. I felt like superwoman.”

At college in North Carolina she majored in International Relations, but found herself more interested in relations of a more domestic kind. A long avenue in her neighborhood was changing rapidly, “old dairy farmers, next to poor African-American families, next to million-dollar McMansions.” She went door-to-door, asking people if she could take people’s portraits.

“I just wanted to know who my neighbors were,” she says. But in projects like this she also discovered the camera was not just a tool for self-empowerment. “I realized that you can give voice and amplify other people's beautiful voices, and that's what drew me in,” she explains.

After graduating, she worked as an editor at the Associated Press in Washington DC for five years. She learned how the news business works and where photography fits in, in particular where the kind of photography she was interested in might feature. “It was just a lot of reaction, and I felt like this was my opportunity to go deep into stories, and tell a longer format narrative.”

Ami plucked up the courage to quit, and headed for Prague. In the glow of the Velvet Revolution, the Czech Republic was freeing itself of 40 years of communism. It felt important, and timely, and romantic. But she found herself on a business paper, taking dull portraits of even duller businessmen and politicians. This wasn’t quite what she’d dreamed of back in DC.

“And then after about a year I started to hear stories about the conflict in Kosovo, and I couldn’t get these stories out of my head, of children fleeing over mountains in the middle of winter. Something inside of me knew I had to go. And so literally overnight, I went from being this relatively amateur photographer to covering this conflict.”

When Ami first pitched stories about Kosovo back to editors in the US, they weren’t interested. It seemed very far away. Then in March 1999, Bill Clinton helped convince NATO to offer air support, and suddenly everyone was scrambling for the very stories they’d just turned down. Ami filed thousands of photographs from the Kosovo War, and felt she could help tell this vital humanitarian story. Until she couldn’t.

“I think it's really important to take a pulse on how you're feeling, because you do get post-traumatic stress disorder and you stop thinking rationally, and I think that's when things go wrong. You have to be 100 percent present and aware of everything going on around you, and I just knew that I was tired and depressed, so I took off.”

These tough environments didn't stop her from photographing though. “From Afghanistan and Gaza to Casamance and Angola, I set down this trail thinking that's how you tell powerful stories to go to conflict after conflict.”

She didn’t even tell her parents where she was going and what she was shooting. It was nearly a decade later when she made a website, that her mum found out and rang her up in tears.

“I didn’t want her to worry,” Ami explains, but again the work was taking its toll. She took some time off, and then in 2009, she got a call from the Nature Conservancy. The US-based charity commissioned her to shoot conservation projects in 11 different places, from Alaska to Australia, over the course of nine months for a book and accompanying exhibition.

“It was like a gift from the universe, because it totally changed the trajectory of my life,” she says.“I realized every single conflict I had covered was always connected to our resources. I started to realize that all these stories about people were always stories about the natural world, and vice versa.”

Then a stroke of good fortune – friends from the Czech Republic told her about an audacious plan to fly four of the last eight northern white rhinos left in the world from Prague’s Dvur Kralov zoo back to Kenya, a last-ditch effort to save the species.

“When I saw these gentle, hulking creatures that had survived for millions of years that couldn't survive mankind, it just broke my heart. I got obsessed with the story, and tried to figure out. We're talking about poaching. We're talking about the challenges, but what's the way forward? What do we do?"

The series was published in Nat Geo in 2014; in early 2018 the news came from Kenya that the last male northern white rhino in the world, Sudan, had died.

It’s crazy. We’re witnessing extinction

“It’s crazy. We're witnessing extinction,” Ami says. But she’s not interested in finger-pointing. When her images pack an emotional punch, which they frequently do, the aim is to use that power to drive forward the search for solutions.

“We have to talk about the challenges we face, but I think we also have to give people a way forward,” Ami says.

“If you sit in your chair and watch the news, the world looks like this depressing, dark, hopeless place. It's easier to show tension and chaos. But the truth is, if you spend enough time in any community, as divided as they may look, there's always hopeful things happening. I don't think we spend enough time giving voice to those narratives as well. But they're always there.”

One of the main challenges is to reconnect people and the natural world as part of the same story. Ami points out that in wildlife documentaries, you rarely see a person, “but I promise you, behind that camera man there's probably 100 people watching.”

So when it came to the rhinos, Ami turned her lens as much on the local conservation workers who were trying to save the species. “They're the greatest protectors and they really hold the key to saving what's left,” she says. And so by empowering them and amplifying their strong voices, I wanted to create a blueprint for other places.”

To tell these stories takes time. The shortest project she’s worked on took a mere four years. Last year she maybe spent three weeks in total at home in Montana, “and not in one stretch.”

“I think to really understand a story, to find all the different threads, it takes that kind of time. I was taught in the beginning to parachute in for a couple of weeks and take the most sensationalistic images. I realized all I was doing was further polarizing people.

“I didn't really create any understanding,” she continues. “Photography is a double-edged sword; it has the power to create awareness and understanding across cultures and countries and continents, but it definitely has the ability to divide and focus on the things that separate us.”

So now she spends weeks building relationships within the communities whose trust she needs to win. “I go and meet the leaders and drink endless cups of tea. And once I get their blessing, it travels like wildfire through the whole community. Suddenly, everybody knows why you're there, who you are, and that you've been accepted by the leaders, and it really keeps me safe.

Safety is an important consideration in many of the places she goes. Paradoxically, Ami finds travelling alone preferable. “I find it’s so much safer than traveling in a group because my antennas are up, I'm super aware of what's going on around me. I can predict when things are gonna go sideways a lot more quickly than when you're wrapped up in a conversation and not paying attention.”

It seems this self-sufficiency is an important part of her creative outlook, as well as her process. She has learned what kind of photographer she wants to be by getting out there and taking photographs. The fuck-ups can be just as enlightening as the award-winners.

“I failed miserably on my second National Geographic story, and they stopped using me for years. It feels horrible at the time, but that's the moment of the biggest transformations. Letting go of the fear is really important. It's never going to be perfect, and what used to paralyze me was that fear of failure.”

This piece is part of our Union of Concerned Photographers series.