In 2015, Tonje Thilesen travelled to Karachi, Pakistan, to meet their internet friends in real life.

Their intention to photograph this bizarre and uniquely millennial phenomenon turned into a life-changing journey where they found solace in a community of artists who had created a space for art and queerness to thrive despite a backdrop of poverty, corruption and violence. Exactly a decade later, Thilesen returned to continue the project, spend time with friends and explore how the DIY scene had evolved. Here, they talk to Gem Fletcher about connection, intimacy and loss and what it takes to nurture creativity in hostile environments.

Making photographs is a process of collecting memories for Tonje Thilesen. They are building an archive of feeling that recognizes the fragile yet uncomfortable truth that nothing lasts forever. It’s less about a singular or definitive approach and more about embracing the messy tendrils of life—the complexity, contradiction and often oddball outsider energy—that conjures work into being.

Take “Unfinished Kite,” Thilesen’s ongoing body of work that began ten years ago as a visual documentation of the bizarre transition from being online to real-life friends. While the original intention is still present in the work today, the project could be described as a reflection on cultural production and Queer world-building in Karachi, Pakistan, while also encompassing climate depression, loss, neurodiversity, freedom of expression and the transformative power of counter-culture. The project’s title is significant here. Named after “Unfinished Swan,” a computer game where a young boy chasing after a swan wanders into a surreal, unfinished kingdom. Players throw paint in a white space to splatter their surroundings and reveal the world around them, mirroring the way Thilesen uses the camera.

I already knew so much about these people and their lives before my arrival but had no sense of their outward selves.

“It’s kind of a wild story,” says Thilesen when I ask them about the genesis of “Unfinished Kite.” Flashback to 2013, and Thilesen and Henning—their online friend from Berlin—would spend days searching the corners of the internet to uncover experimental and DIY musicians making techno, footwork, pop or ambient field recordings from their bedrooms. Bonded by their shared affection for micro labels, cassette tapes and DIY house shows, the duo would write about their findings on their music blog, “No Fear of Pop,” building online friendships with musicians and producers worldwide.

In 2013, Thilesen came across a record by Asfandyar Khan, a Karachi-based ambient musician, on Bandcamp, and immediately loved it. “I wrote to him straight away,” recalls Thilesen about the exchange. “Are you part of a larger group of people that make music? What’s the story?” Over time, they became internet friends. Asfandyar recommended a list of bands based in and around Karachi, ranging from shoegaze to electronic music, which Thilesen would then write about on their blog. Two years later, they finally met in person.

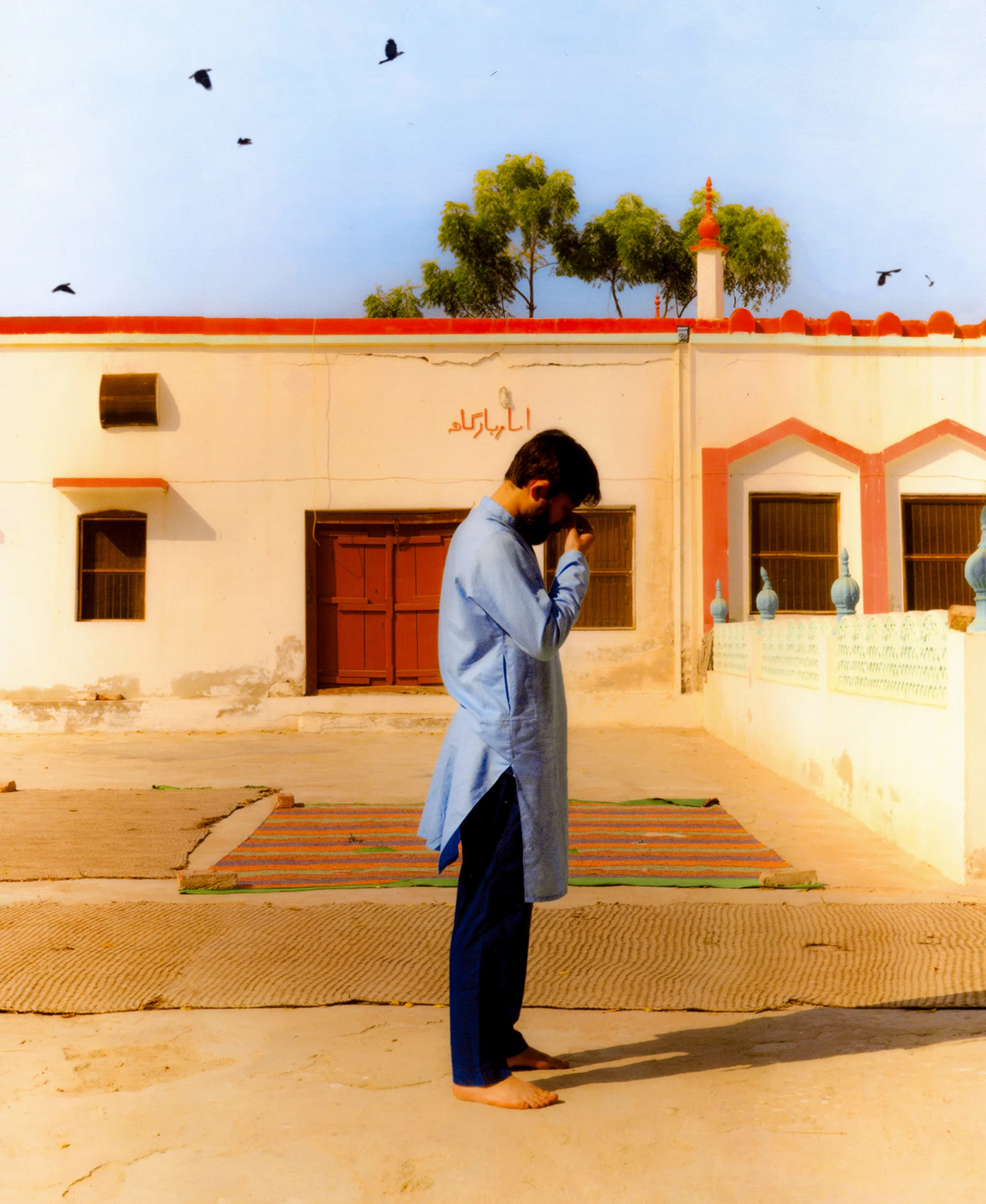

During their time in Karachi, Thilesen documented the underground music scene and got to know their internet friends and their extended network of artists, sculptors, photographers and musicians. “I already knew so much about these people and their lives before my arrival but had no sense of their outward selves,” explains Thilesen. Karachi itself was very conservative at the time. People did not discuss politics out in the open, and it was rare to see women walking around in the streets. “The reality of poverty and corruption was still very much a backdrop to life there,” says Thilesen. “We hid our phones in the trunk of the car when going from one house to the other and kept cash handy in case we got stopped and harassed by the military.”

Despite the fraught social and political environment, Thilesen found the alternative community in Karachi to be a “bastion of progressive thought.” At the center of this was The Second Floor, aka T2F, a two-story café and rehearsal space reserved for discussion, music, performance and art. T2F was founded by Sabeen Mahmud, affectionately known by the community as “the feminist mother of the Karachi DIY scene.” Mahmud opened T2F in 2007, and the space was an instant success amongst creative circles—a thriving alternative outpost inspired by the “Karachi that existed during Mahmud’s parents’ youth in the 1960s, where tea houses were filled with leftist poets and political discussion and long nights would be spent listening to music at the local clubs.” T2F was also Queer-friendly at a time when it was dangerous for the LGBTQ+ community to be visible and out.

Despite poverty, corruption and violence, Thilesen and their friends thrived creatively, finding solace in the community, blooming in and around T2F. “A couple of days before I was supposed to leave Karachi to head home, I was at a friend’s house when we got word that Sabeen had been shot and was in critical condition,” explains Thilesen. “A few hours later, she passed. It was a devastating loss, made more poignant as I was documenting the DIY scene’s success.”

The ramifications of Mahmud’s murder sent shockwaves through the community. Although Thilesen had planned to return to the city every few years, fear and loss made them cautious. Friendships remained close but reverted to being primarily online until Thilesen returned to Pakistan earlier this year. This time, they found Karachi changing with a new generation making their mark on the independent scene. Venues and initiatives had emerged in the ten years since they left, local artists were thriving, and overall, they observed life feeling safer and more open for the community.

“There is more Queer visibility in Karachi since I was there last, so I wanted to find subjects who weren't afraid to take up space—quite literally—in public, regardless of sexuality,” says Thilesen. “I made images with Asad Zulfiqar, a non-binary multidisciplinary artist, Mashal Hussain, a soccer player and coach who helps run an all-women soccer team, Osama Doger, an incredible photographer who flew in from Lahore, Lyla, a techno DJ and producer and Tee, a young fashion design student.”

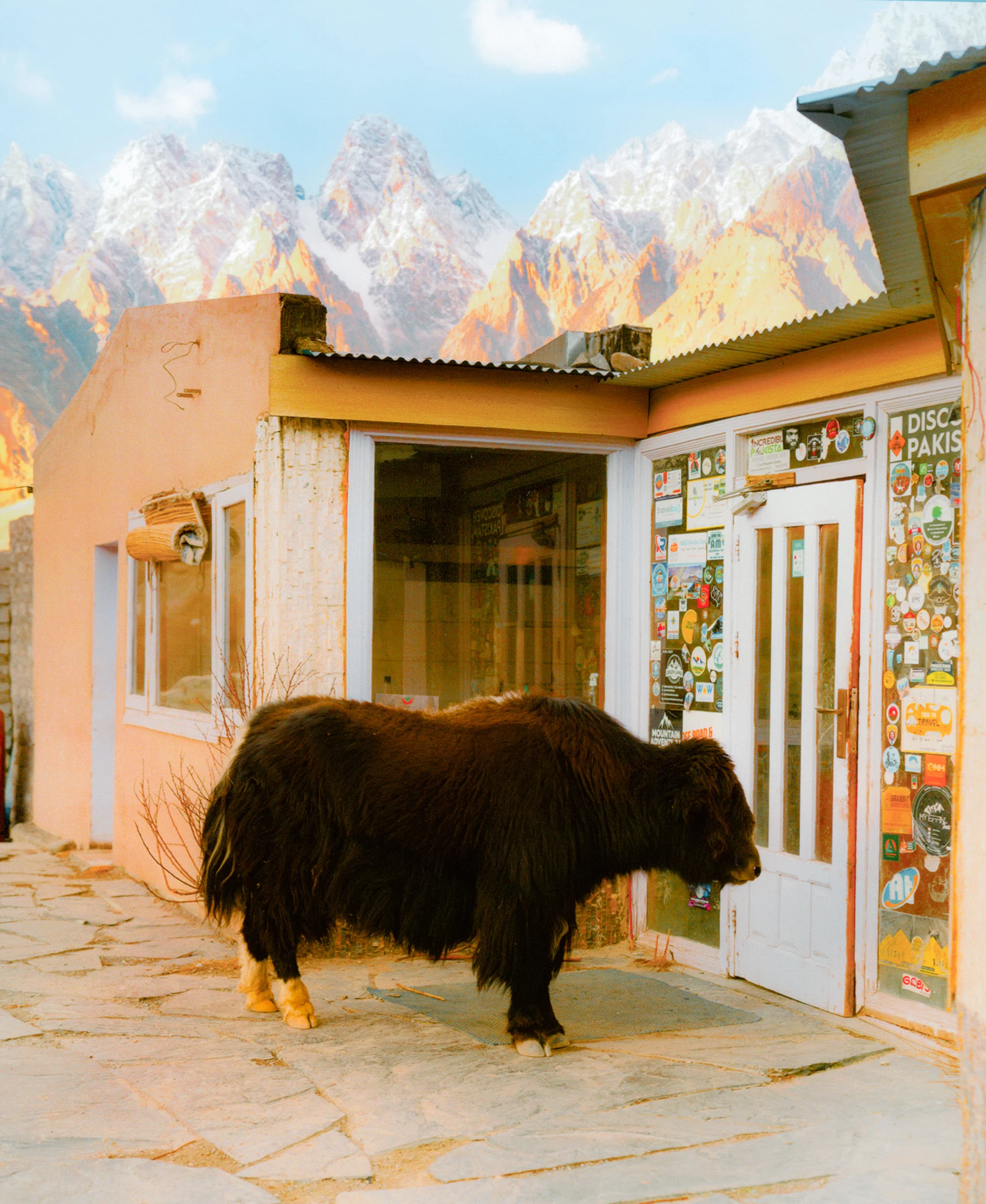

In addition to new connections, Thilesen reconnected with old friends Humayun, Talha and Samya. “Together we spent a week travelling to Hunza and Skardu in Gilgit-Baltistan to hike in the spectacular Karakoram mountains. Travelling there during the winter can be tricky due to snow storms, but none of my friends had seen snow before, so we decided to take the risk.”

There is more Queer visibility in Karachi since I was there last, so I wanted to find subjects who weren't afraid to take up space.

Over time, “Unfinished Kite” has become an archive for Thilesen’s experiences in Karachi over the last decade. It’s a world to play in, a way to connect and, perhaps most pertinent, to visualize what it feels like to be alive in an ever-changing world. Like all of Thilesen’s work, the images are both tender and surreal, with every frame rich with unexpected colors, gestures and compositions heightened by the love and joy that bonds the community. “Just like I knew as a 13-year-old getting into photography that the dragonfly I’m photographing might not be here in 25 years,” says Thilesen, “I need to translate and preserve the joy, curiosity and beauty I feel in these friendships. It’s pretty simple.”

Creativity should be captured, and for a photographer, having the right equipment can be a crucial ingredient in doing so, allowing them to express themselves fully and do their subjects justice. With a dynamic pricing engine and a circular business model, MPB makes camera gear easily accessible so creatives of all kinds can share their stories. As two platforms that pride ourselves on enabling creativity to flourish the world over, this year, we’re curating some of our photography stories in partnership with MPB, the picture-perfect camera platform.