We talk a lot about artistic freedom, but creatives have responsibilities too. We expect more from them – for artists, writers and musicians to make sense of the darkest, saddest and most overwhelming human experiences.

Rob Alderson and Lucy Pike explore how photographers grappled with the refugee crisis...

This piece is part of our 2016 Review of the Year where we looked at a few key trends shaping the creative world.

The pressure is intense when photographers have to document something like the European migrant crisis, a story of almost inconceivable numbers and excruciating individual tragedies. And when that story keeps on going – when weeks turn into months and months turn into years – how do creatives find new ways to tell such a depressingly unchanging tale?

Giles Duley is a photographer who has dedicated his practice to documenting these kinds of narratives, from the refugee crisis itself to his Legacy of War project.

“So much journalism and photography these days is rushed because of necessity – immediate deadlines, dwindling budgets, the hunt for the next story.

“With the refugee crisis, that’s particularly true. Many families and communities are in limbo, their lives stuck. You need time to tell that story.”

This need for patience is further complicated by the scale of the migrant crisis and the difficulties most people have getting their heads round it.

“The refugee crisis is often expressed in overwhelming statistics and photographs of nameless faces and crowds,” he says. “The secret is to make sure the story doesn’t get lost behind the concept.”

“Sometimes I see work that leaves you wondering if it’s helped you understand a situation or gain empathy with those being documented. If you can be original and achieve that, then that story will have the greatest impact.”

With the refugee crisis, that’s particularly true. Many families and communities are in limbo, their lives stuck. You need time to tell that story.

But back in the early days, when Hugo and Orpheo secured a three-month lease on the former brothel, and got a small grant to develop their nascent idea for an online radio station, they never imagined where they would be today.

“We never thought this would be a job like it is now,” Hugo says. “Now we make a plan for the year, kind of. But for years it was step by step. The mentality is still, what can we do and who can we work with? And that is a good thing because we are more aware of our identity – go with the flow and get involved with people we feel connected to, whether that’s a hip hop or a metal artist, a big museum or a small gallery.”

Orpheo agrees. “I am quite happy we didn’t start with some sort of masterplan. That would have been a bit boring. In the beginning it was make the station happen, then survive for a year, then stay in this building, and then make it a job.

“We made many, many, many mistakes,” he laughs. “Everything has been organic; choosing shows, choosing music, choosing who to work with and who not to work with.”

Daniel Castro Garcia is all too aware of this struggle for impact. Along with graphic designer Thomas Saxby, he spent several weeks travelling through Europe and meeting those caught up in the crisis. What struck him was the way in which the media coverage of the migrants had become horribly depersonalized.

“Boats would arrive and 30 or 40 photographers would be waiting on the shore, cameras ready, snapping like lunatics, with women and children falling into the water,” he remembers.

“I think the drama of these images do very little to represent the complex reality of the situation. If anything, they have served to fuel and intoxicate parts of society and change public opinion.”

Daniel’s own photographs, which he is publishing in a Kickstarter-funded book called Foreigner: Migration into Europe 2015–16 seek to restore the empathy he found so lacking in the point-shoot-file-move on mass media approach. Shot in different postures and with different props, Daniel’s work is warmer and more intimate than what we are used to seeing.

“I wanted to photograph this crisis because I felt that what I was seeing and reading was not good enough. It was not acceptable,” he says.

“There are always going to be incredible, dramatic images of conflict situations and humanitarian crisis but this project was about more than that. I always wanted the camera and the photograph to offer dignity and an opportunity for self representation.”

The refugees were looked at like fish in a glass bowl: prodded, confined, filmed, entertained, fed, deserted.

Photographer Alistair Redding faced similar challenges to Daniel when he went to spend a weekend in the infamous Jungle refugee camp in Calais. Writing on his website, he explains how he was acutely aware of coming across as one of the “free agent hipsters dropping in to capture a few snaps, speaking to refugees and generally adopting the journalistic pose.”

He noticed that the refugees in Calais, “were looked at like fish in a glass bowl: prodded, confined, filmed, entertained, fed, deserted.”

He too was intimidated by the fact that having been in the news for so long, people were at best baffled and at worst bored by the crisis. The global attention span is short, but that’s where he believes photography comes in.

“The reaction I often get is that people feel powerless to do anything about the refugee crisis, they feel overwhelmed by the problem and dismayed by the way politicians have either failed to deal with the issue in a humane way or used the issue for their own personal political ends.

“I believe the power of photography is its way of stopping the story or pausing it and allowing us to think about the complexity of every moment.”

Alistair is excellent at picking out small details that build a layered portrait of life in the Jungle – the battered second-hand bikes, the can of some sinister-looking spray hanging from a policeman belt. He also finds disarmingly simple ways of making us re-think the broader things we know about the crisis – a picture of a crew split between two photographs for example is a gut-punchingly powerful way to re-make the point about the number of migrants massed in this tiny corner of north France.

“I’d like to think that my portraits disarm the viewer and perhaps elicit introspection about our beliefs around borders, nations and what responsibility we have to one another,” he writes.

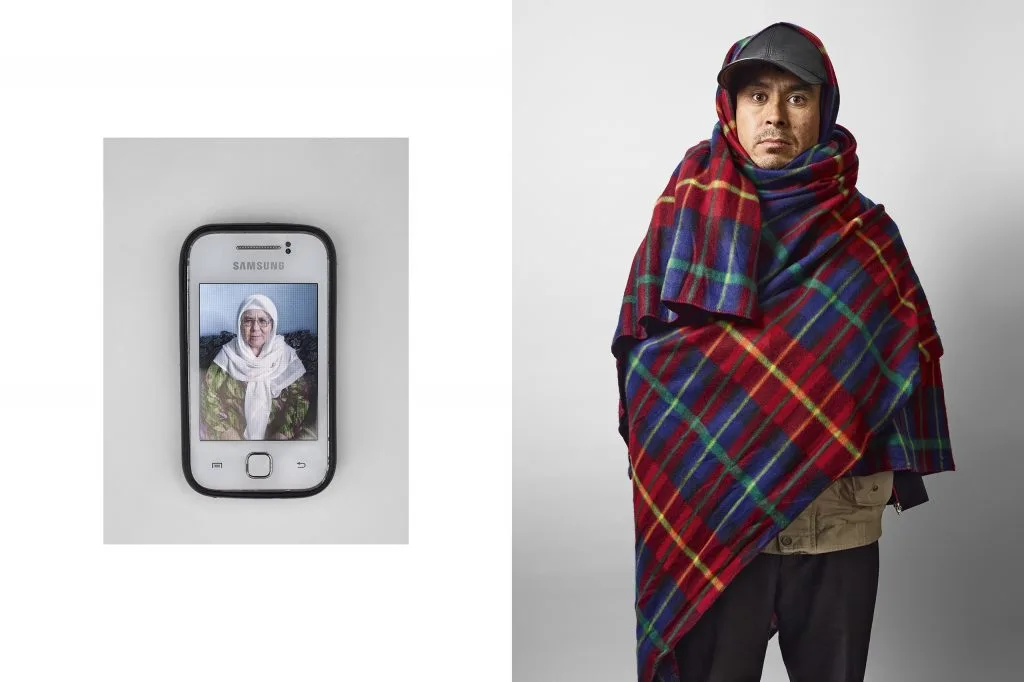

For James Mollison, the drive to create compassion led him to photograph refugees with the possessions they had brought with them to Europe. Shot on neutral backgrounds, they invest huge meaning in the simplest of items – a blanket, a phone charger, a packet of insulin.

He says, “I was interested in looking at individual experiences in what newspapers were calling ‘a flood of people.’

“By stripping away the environment, I try to make portraits through which the viewer can engage with the subject, and not get distracted by the context.” The poignancy of the possessions James came across was heightened by the stories he heard from the people he photographed.

“The people smugglers had ordered people to throw their bags into the sea when crossing by boat from Turkey to Greece, so they had saved just what they could fit into their pockets and jackets,” he says.

“What most caught my attention was images of the lives that people had left behind, or images of family who had been lost along the way.”

Perhaps this gets to the heart of how photographers – and other creatives too – can cut through the noise and find ways of bringing the migrant crisis to life for a jaded and confused general public. It’s important to stop thinking of a single story – impersonal, enormous, somewhere-else – and start thinking of the hundreds and thousands of individual stories – desperate, unique and closer to ourselves than we might care to imagine.