Theo McInnes and Thomas Ralph went to the Isle of Portland in Dorset intending to capture a portrait of a place. Instead, they ended up spending over a year documenting the men seeking asylum aboard the Bibby Stockholm, and the local community that rallied around them. They tell Phoebe West about the resulting collection of warm, intimate photos, titled “Bibby Boys,” the incredible impact the experience had on them, and their hope that the story can inspire compassion and kindness in anyone who sees it.

Thomas Ralph grew up in Dorset, spending summers on Weymouth beach where he remembers seeing Portland “jutting out into the sea” on the horizon. “It's a forgotten place” he says, “with all of the issues that are happening all around the country, but on this micro scale.” Home to 13,000 people, five quarries, three lighthouses, two prisons and one industrial port, the isle is one of the most economically challenged areas in the UK, battling low wages, a housing crisis and dwindling industry. In the summer of 2023, the Bibby Stockholm was moored there—a maintenance barge, repurposed by the UK government to accommodate 500 men seeking asylum from around the world.

Unaware of its impact, Ralph and McInnes arrived in Portland and were immediately struck by the response of locals towards the barge when they asked about it in a local caf: “They said ‘Baint narn of we,’” explains Ralph, “which is basically old Dorset dialect that means, ‘not one of us’”. Though, on leaving the cafe, they were approached by Laney, another local, flyering for the Portland Global Friendship Group: “it was such a fleeting exchange we had with her,” remembers Ralph, “but it really stuck with us.”

The Portland Global Friendship Group formed when the Bibby arrived in Portland as a support network for the men on board: “Just an amazing group of people,” McInnes explains, warmly. “They had no funding—they were just a group of volunteers who, for an entire year, more or less dedicated their lives to making sure these men had an outlet to do things, to talk to people and to be with each other.” Disallowed from working under UK law, people seeking asylum receive £8.86 per week from the government, and little else. “The Friendship Group got [the men] SIM cards, clothes and suitcases,” McInnes explains, “they gave them activities and things to do.” Over more than a year, Ralph and McInnes documented the men aboard the barge, and the incredible community that rallied around them, for their series “Bibby Boys.”

They were just a group of volunteers who more or less dedicated their lives to making sure these men had an outlet.

During their time on the Bibby, residents endured an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease in the water supply, and the tragic death of Leonard Farraku, all amid a national wave of violent anti-immigration riots and government threats of deportation to Rwanda. Upon a floating island, the men aboard the Bibby remained detached, and literally at sea—severed from communities. Formed by a collection of locals when the Bibby arrived, the Friendship Group began to take shape at a town meeting where people discussed how they could help—spaces they could make accessible and hobbies they could share with the men: “this amazing thing happened,” Ralph says, “where people just started putting their hands up, and what started as five people in a WhatsApp group grew into a network of hundreds.”

What followed was a joyous time of reciprocity and collaboration—events and excursions; building projects; people fell in love and neighbours met for the first time; queer spaces opened up in the community where none had existed before; the cricket team went from obscurity to success thanks to their Afghan players. McInnes recalls in awe how much the guys from the Bibby wanted to give back: “I was amazed at this quality in them,” he says, “you know, coming over to this country with basically a rucksack and whatever else they have on them, and wanting to just give as much as they could.” It wasn’t all easy; those leading the Friendship Group were the targets of vitriol from locals and online hate, and an exhibition of “Bibby Boys” itself came under attack, but it only served to highlight the importance of what the project was trying to do, and make them think more deeply about where it can go.

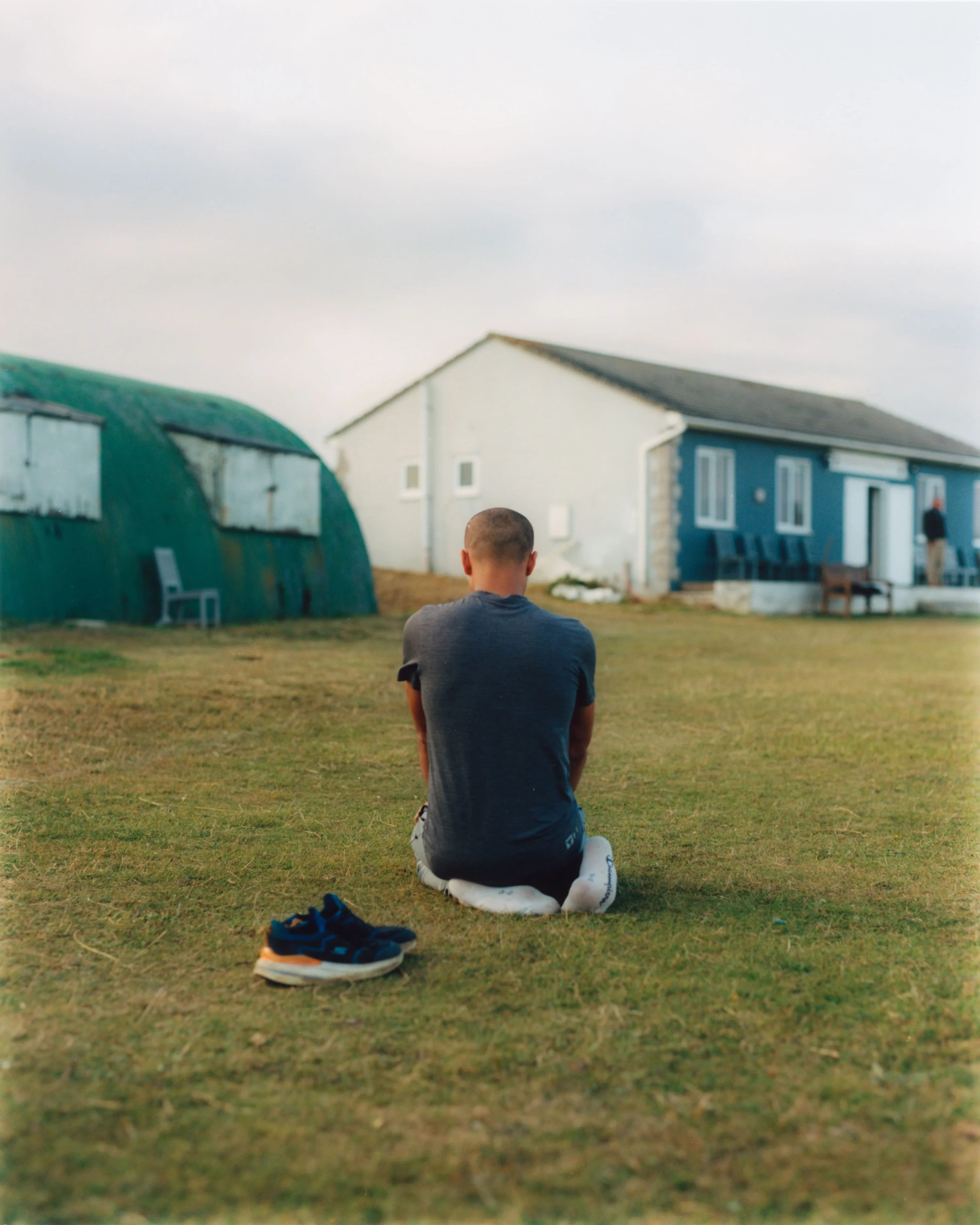

All of the images were shot on film: “Film’s permanence, the consideration it requires, and the beautiful results it develops became important factors in rewriting the narrative around this story and this time of limbo,” explains Ralph. There’s a softness to the images which feels in stark contrast to the way that immigrant men are portrayed in mass media today, as violent and dangerous—to be feared. Where each of the men on the barge had come from, and what they had endured, was not lost on McInnes and Ralph, but their portraits have a gentle quality and richness, which speaks to the whole lives, hopes and futures of these individuals seeking asylum.

I was amazed at this quality in them [the men seeking asylim]. They wanted to just give as much as they could.

One day, The Friendship Group arranged a barbecue on the beach. “I remember that being one of the most amazing nights of my life,” Ralph says. “Here I was in Portland, near where I grew up, having conversations with guys from all around the world—everyone was sharing food and stories and music. It was just incredible." That evening, McInnes and Ralph walked a group of the guys to catch their last bus back to the Bibby, revelling in the company of new friends, and felt the jolt of their absence as they were left on the pavement. “I remember being really struck by how much we were getting on with the guys and how joyous it was,” reflects Ralph, “but then just how confusing it was that they were basically going back to this prison boat, where they would be six to a room…and not really knowing how to process that.”

Hearing about time spent with the Friendship Group and the men from the barge is to hear in abundance of the extraordinary things that ordinary people are capable of. So much of “Bibby Boys” feels like a celebration of small gestures, bearing witness to the power of solidarity that can be felt among strangers with simple acts—and what that can become. “How can we encourage people to form their own groups and to extend a hand of friendship to the nearest hotel, with people seeking asylum in it?” Ralph wonders. “Even if you're already in support, just to get off the sofa and actually do something.” The Friendship Group remains in touch, with many of the men having now moved around the country, and others are forming, inspired by its effects.

What began as a project intended to profile Portland as a place, then individuals from the Bibby, ended up becoming both—a beautiful tribute to all the things that happen by osmosis when communities are left to thrive on a human level. The barge left in November 2024, leaving nothing in its wake but a web of compassion and humanity. “I wish a lot of people could actually experience that—we didn’t really know that it was going to go that deep,” says Ralph, trying to articulate the inarticulable of what they stumbled across and captured over a year. “If people can come away from our photographs with that feeling, or a sliver of that feeling, then we’ve done a good job.”