In India, magic has never simply been entertainment. Rooted in storytelling, myth and spirituality, it was once considered a sacred practice—part ritual, part spectacle. Filmmaker Tara L.C. Sood was always drawn to its history and heritage, its living presence. In her short film, The Great Mandrake, she turns her lens on contemporary Indian magicians to honor their role as cultural custodians. She tells Ritupriya Basu how she created a cinematic space where vanishing traditions breathe again, where audiences are invited to surrender logic and rediscover the wonder of not knowing.

Not too long ago, it would have been common to find a magician sitting outside a railway station in India with a basket in front of him. A little boy would climb into the basket, the lid would snap shut, and the magician would furiously stab through the wicker with a sharp knife. Minutes later, the boy would emerge with the blade sticking through his neck, but, of course, alive—the audience would erupt. They would have just witnessed the Basket Trick, one of the most famous feats of Indian magic, or jadoo.

Magic is… one of the few places where you willingly go to surrender control. To me, that’s profound, sitting in comfort with the lack of explanation.

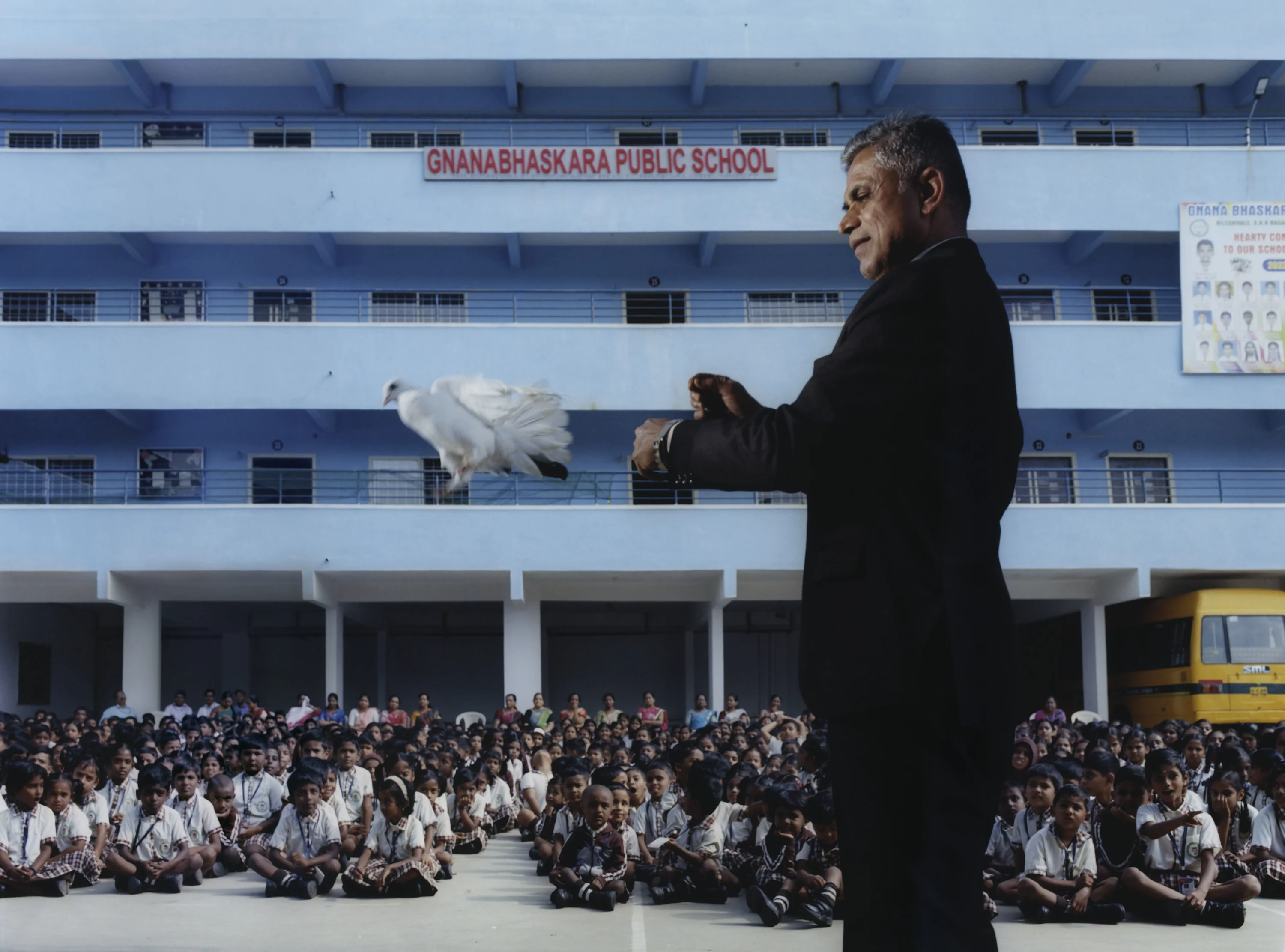

Jadoo has always existed in this space between reality and spectacle. “For me, Indian magic was always about a return to childhood,” says French-Indian photographer and filmmaker Tara L.C. Sood, who invited the 10 most famous street magicians in southern India to perform at a fictional magic convention in Bangalore for her short film, “The Great Mandrake.” “When we grew up, we started to categorize and control everything in order to feel safe. Magic is the opposite. It’s one of the few places where you willingly go to surrender control, to be complicit in deceit. To me, that’s profound, sitting in comfort with the lack of explanation. And by choosing to be tricked and not digging too deep, you are making a subversive act of trust.”

On the streets of India, this exchange of trust and deceit between magician and spectator has been playing out for thousands of years. In fact, it is difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain the origin of magic in the country. The Atharva Veda, one of India’s oldest and most influential sacred texts, brims with descriptions of magical rituals, incantations, charms and spells. The concept of Maya (illusion) is central to Hindu philosophy, influencing both religious thought and performative arts. “In magic, tricks are never just tricks,” says Sood. “They’re framed within mythological or moral storytelling. The rope is never just a rope. It’s also a reference to Maya and Lila, the cosmic play of illusion. So, storytelling and spirituality have always been woven into magic.”

The film… grew out of an urgency I felt to document vanishing traditions in India.

While rich in its cultural underpinnings, magic in India has steadily receded from public life. Once a familiar spectacle on street corners and at railway stations, it is now rarely seen outside of staged performances or digital platforms, its place in everyday culture diminished by cinema, television and the internet. That sense of disappearance is what compelled Sood to make “The Great Mandrake.” “The film, and the accompanying photo series, grew out of an urgency I felt to document vanishing traditions in India,” says Sood. “I often work with the idea of ‘invented archives’ or records that don’t really exist, but that I create as if they did or deserve to be. It’s my tiny contribution to keep my culture from being forgotten.”

His shadow puppetry brought us all to tears. No one could look away.

For Sood, magic was the perfect subject, having always felt a certain kinship with it. “I have always lived in fantasy. I love things that are unresolved, that resist conclusion—the uncanny, the conspiratorial, the inexplicable. But I also always keep one foot in reality; that balance is where the work lives,” she explains. “For me, this project was about creating a space in which things would just begin to happen on their own. I could construct a world around the magicians, but they did the rest. After a certain point, I’m not manipulating anything anymore, and I go back to being an observer.”

Each of the performances featured in the film was shot in old cinema halls dotted across Bangalore, further underscoring Sood’s interests in the layering of disappearing traditions. Across India, single-screen “talkies” are quickly vanishing sentinels of the past, elbowed out by slick multiplexes. “If it weren’t for the few philanthropists and fans who remember the act of going to the cinema as a form of escapism when they were children, these places would probably have disappeared already,” says Sood. “Because the money they make on a few screenings a week cannot support the running of these incredible buildings.”

The atmospheric hallways and curtained stages of these talkies open into another world, making space for a talented cast of magicians from across South India. Each carries a different story. Some have inherited their acts and props, carrying forward family lineages. Others work independently, building their own repertoires. Some travel constantly, and others stay closer to home, mentoring young performers.

Amongst the ten illusionists seen in the film is Prahlad Acharya, one of the most famous magicians in India. “In the film, he performs shadow puppetry. He has had the most extraordinary career as an escapist magician. He told me he used to get himself thrown into the Ganges, chained up inside a box, and would find a way out,” says Sood. “His shadow puppetry, although a completely different type of magic, brought us all to tears. No one could look away.”

I wanted my audience to see these magicians not only as entertainers, but as custodians of cultural memory.

When the magicians take the stage, the intertwining connection between jadoo and spirituality is palpable. There’s a certain reverence in their craftsmanship. As Sood points out, like so many art forms in India, magic is meticulous and intellectual. It demands patience, learning, and longevity. “For me, the most moving part of magic is the moment of surrender and when the audience decides not to understand,” says Sood. “That choice, to relinquish the safety of explanation, feels deeply spiritual. There were many times the crew and I could have uncovered the tricks we were watching—we chose not to.”

Indian magic, in all its complexity, once enthralled the world, inspiring both the wonder and frustration of many a magician in the West. Foreign magicians travelled to colonial India to learn local jadoo, and then took it back to the West, adapting what they had learnt and using it as a centerpiece in their acts. As part of her research, when Sood spoke to John Zubrzycki, the author of “Empire of Enchantment: The Story of Indian Magic,” she learnt how Indian magic was borrowed, erased, but also carried forward in surprising ways.

“What’s interesting is that today there’s real admiration between Indian and Western magicians, a recognition of each other’s craft rather than just imitation,” she says. “For me, the focus was never on loss but on resilience. I wanted my audience to see these magicians not only as entertainers, but as custodians of cultural memory. By giving these traditions space on screen, I wanted them to feel alive and present, not like something left behind.”