For image-maker Tantolohun Ayanda, Lagos has always been the muse, whether he’s drawing inspiration from its bustling streets and the energy of its people or by old family photo albums and the parties his grandma would take him to as a kid. He tells Kyle MacNeill how the place seeps into every aspect of his work, and how he uses photography as a way to immortalize the experiences he’s had there.

There’s a permanent recollection of imagery in Tantolohun Ayanda’s mind. “When I was [a child] I used to go with my grandma to African parties. I still remember the way they behaved, the attitude, the atmosphere, the style, the clothes, the happiness, the facial expressions, the greetings, everything. Oh, I love this style,” Ayanda, known as Tanti, says over Zoom. “I said to myself, now this is going to be my style.”

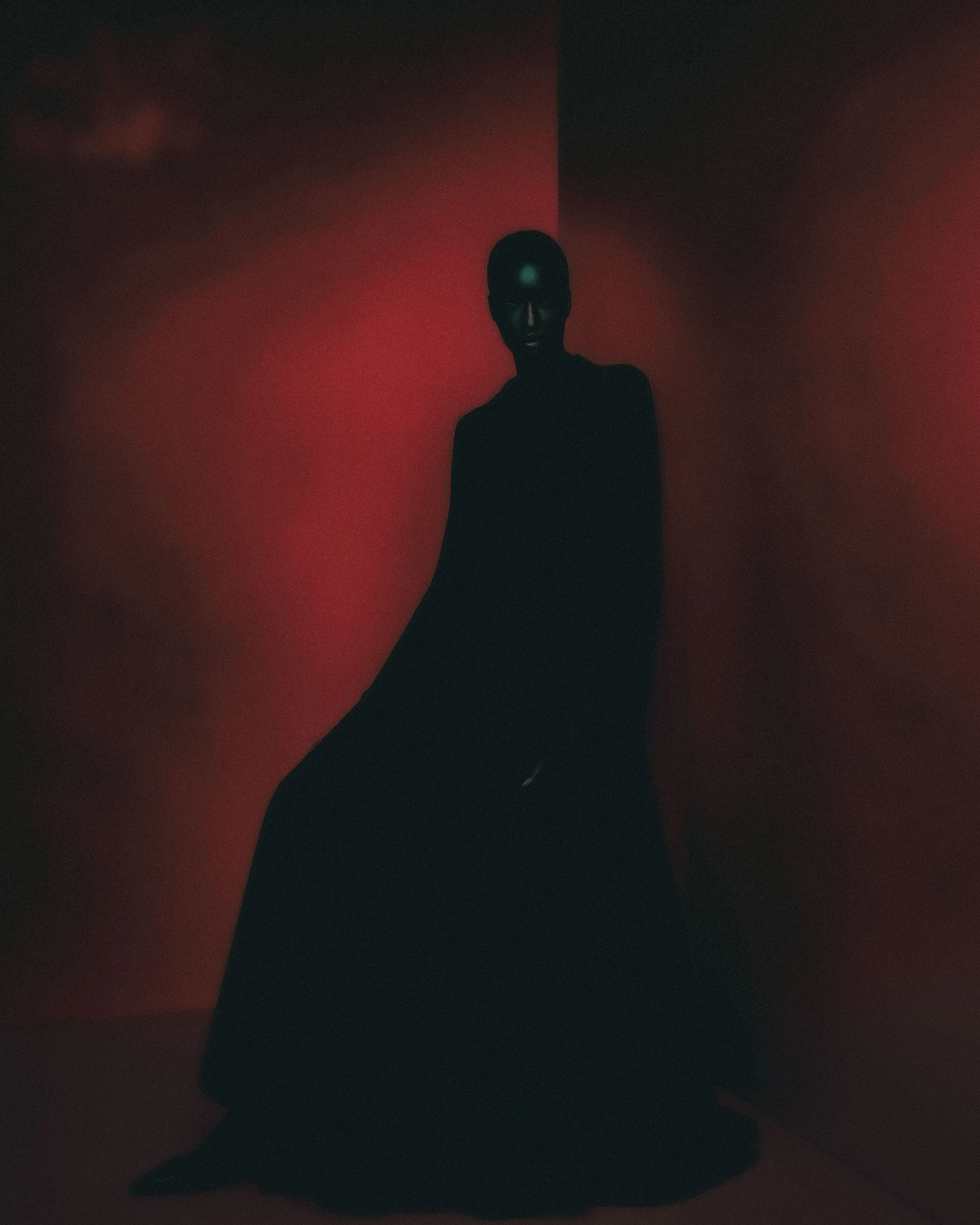

This memorable aesthetic, imbued with personal nostalgia, is the lifeblood of the Nigerian image-maker’s work. It manifests itself in his rich, uncompromising photography of the local community and studio shots, obfuscated with opaque forms. The camera, for Ayanda, doesn’t capture ephemera; it immortalizes experience.

For the entirety of his childhood, Ayanda couldn’t afford an actual camera. “Back in 2014, I was using a Blackberry,” he explains. It allowed him to focus on the story, rather than get lost in the granular settings of a DSLR. “You just have to do it. It’s going to take time for you to get a camera, but you have to do something,” he says.

Ayanda grew up in Ketu, Lagos with his grandma. “Life with my Grandma was the best, I think I was the luckiest kid who was provided everything including discipline because my grandma don’t play about that,” he says. Inspired by her photo albums, he tried his hand at photography with work experience at church. “We were told to come to church for class to learn photography and videography. So I went for seven days,” he remembers. Later, he learnt graphic design through an artist in Ketu, which sharpened his compositions. “I understood how to edit my photographs to make the shadows like this, or the highlights like this. That was really cool,” he says.

At 18, he used his savings to buy a Nikon D3200. But while he upgraded his equipment, his original vision was still just as exacting. Photography isn’t just Ayanda’s life, but vice versa, too. “I need life in my photography,” he says. For him, that vitality derives from the models he chooses to use: real people. “You don’t need to be tall to be a model. I love using kids for my photography as well,” he says.

Lagos, in all its paradoxical beauty, is the lifeblood of Ayanda’s work. “Every day, I saw people fighting, commotion—it shaped my career,” he says. “Everybody on the street is mad, crazy, angry. The markets! Come to Lagos and see for yourself.” He’s keen to travel outside the capital. “There are some places in Nigeria I really want to go to to take pictures, but it’s not the time yet.” The West African country is, in all its dynamism, Ayanda’s ideal setting for his artform; and he finds energy in the people. “It’s blessed, the best place to take your photography. I actually love it. The people are just so sweet.”

Shooting in urban areas isn’t always a seamless experience. “Sometimes it’s challenging to take pictures on the street because people complain. But if I travel somewhere new, I'll make sure I walk around there for a few days so people have seen me,” he says, emphasizing the need to build trust. Others, though, are actively keen to be featured. “Sometimes people will be begging me, ‘please take my picture now.’”

It’s blessed, the best place to take your photography. I actually love it. The people are just so sweet.

But while he’s got to grips with representing the lively spirit of Lagos, he always casts dark shadows across his work. “We’re not happy here in Nigeria. We don’t have light normally, so most of the time we stay in the shadows,” he reflects. “People are just buzzing [around] to make means. But the government is not doing what they’re supposed to do.”

Even when he’s shooting indoors, life outside pours in. “The spirit of Lagos or Nigeria as a whole is always present in my work,” he says. His studio imagery sees female models with flawless hairstyles superimposed on opaque backgrounds, often sitting symmetrically and obscured by the shadows that shroud Ayanda’s work. Heady scarlets and crimsons pierce through. “I feel like the strongest artistic color is red,” Ayanda says. “Why did God, the greatest creator, make human blood the most vital red? There’s a way red communicates art that other colors can’t.”

Whatever happens in Ayanda’s own future, it will always be informed by the imagery of his past, his memories of Lagos interwoven with mementos. “All these memories, memories, memories,” he says near the end of our call, as if chanting. ”I need these memories. Creating memories from memories again, again and again.” He pauses, lost in the slideshow of his mind’s eye, then asks: “Do you understand?”