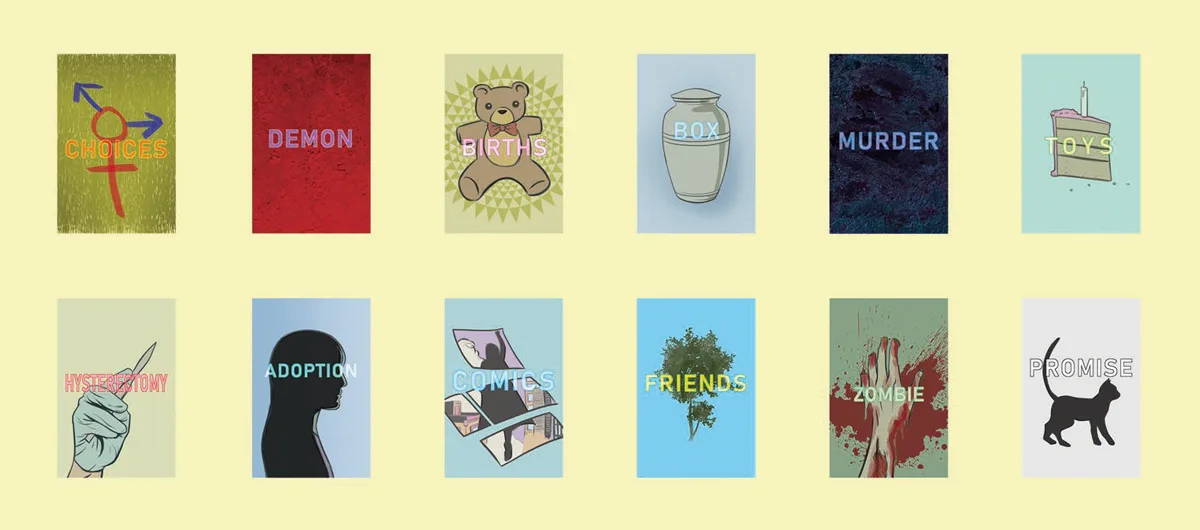

Sleeping While Standing is the debut autobiographical comic by Japanese-American artist Taki Soma. The publication is split into four-page chapters, each one dealing with a different theme from Taki’s life, from love to teen angst to the separation of her parents. She tells Jyni Ong about the stories from her past that stand out for her, and about how recreating each moment became a form of therapy for her.

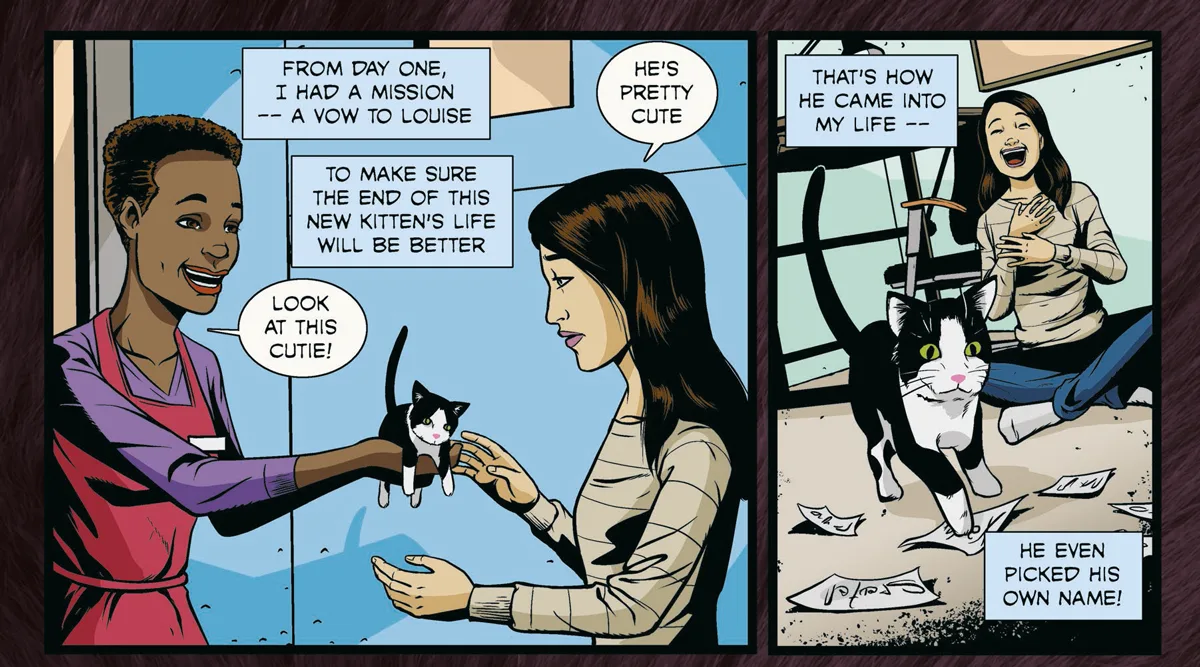

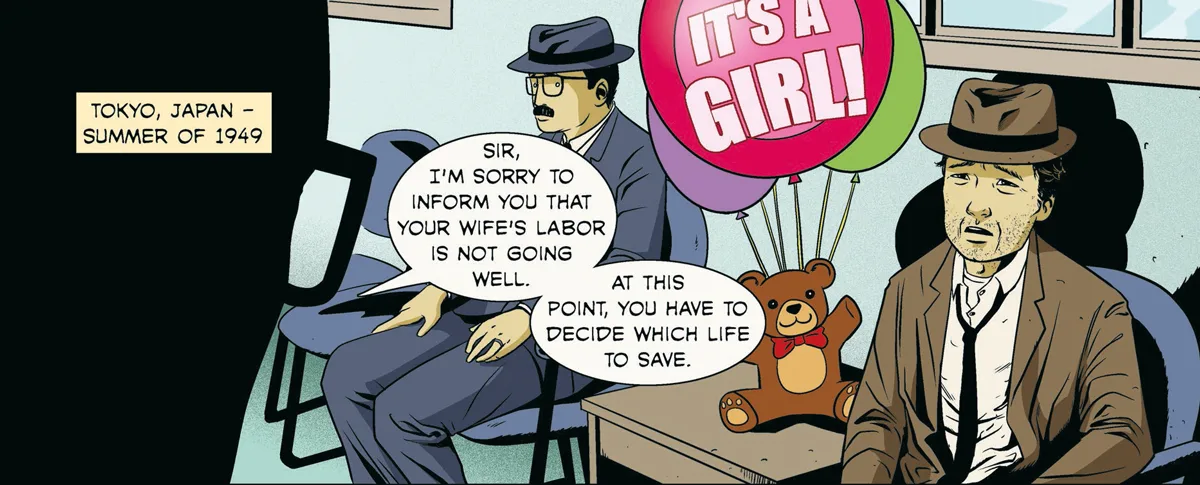

“There is no limit to what you can do with the storytelling,” Taki Soma says when I ask what first attracted her to comics. The Japanese-American artist has just released her first autobiographical publication,“Sleeping While Standing.” A collection of moving and funny stories, the 100-page-long volume takes us on a tour of Taki’s life thus far. From her early childhood in Japan in the 80s to emigrating to Minnesota as a teen, the digitally rendered comics tell stories of love, childhood trauma, teen angst, death, drugs, parental separation, and health issues.

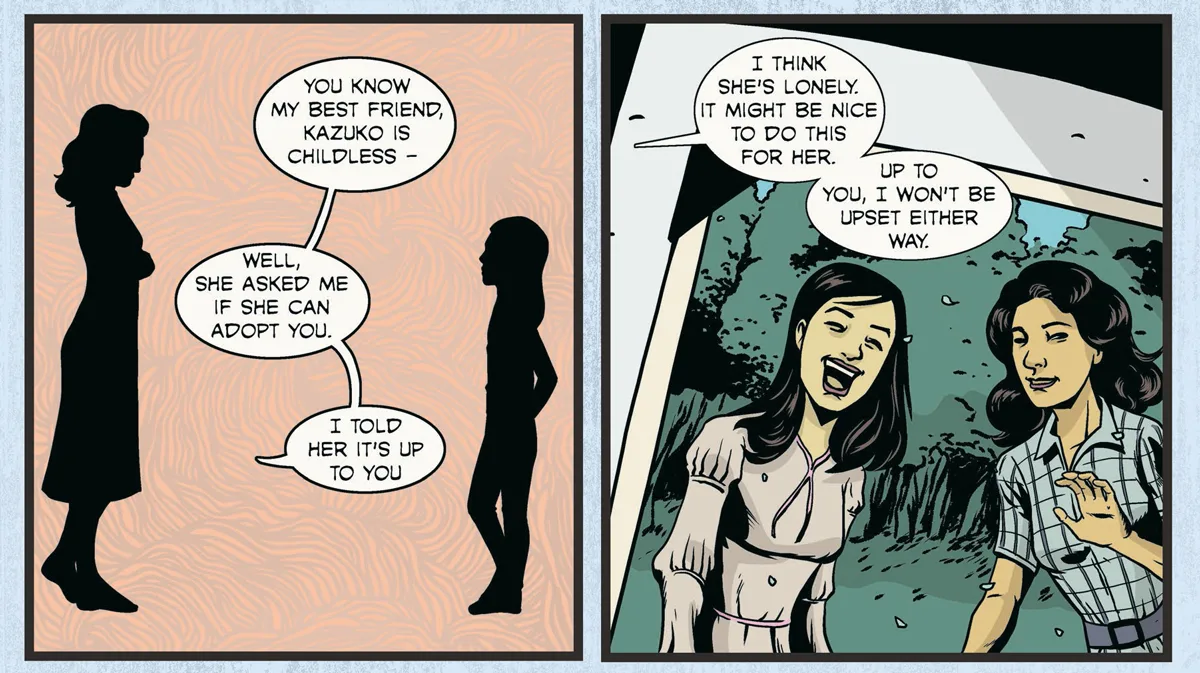

Published by Avery Hill Publishing, “Sleeping While Standing”has been one-and-a-half years in the making. Each vignette is only four pages long, a conscious decision by the Hugo Award-nominated artist imposed as a way to address trauma in a digestible way. “I didn’t really have a plan for it,” she tells me. “When I first started working on it, I just did the one story because I didn’t know how else to process the pain I was going through.” After the first story was complete, she thought, “this is a really good, therapeutic thing. And whatever subject I tackle, within four pages, it's not so bad.”

Speaking of the relationship between autobiography and therapy, Taki explains how she came to pour her feelings into the work. “It wasn’t the kind of pain that I actually wanted to let go. I wanted to remember it, I wanted to process it,” she says. Importantly, “Sleeping While Standing”was created “just for [her]self,” a way to process in a somewhat linear way. That being said, Taki still considered the reader’s point of view, ensuring they can empathize with the protagonist and find their own resonance in turn.

There is no limit to what you can do with the storytelling in a comic.

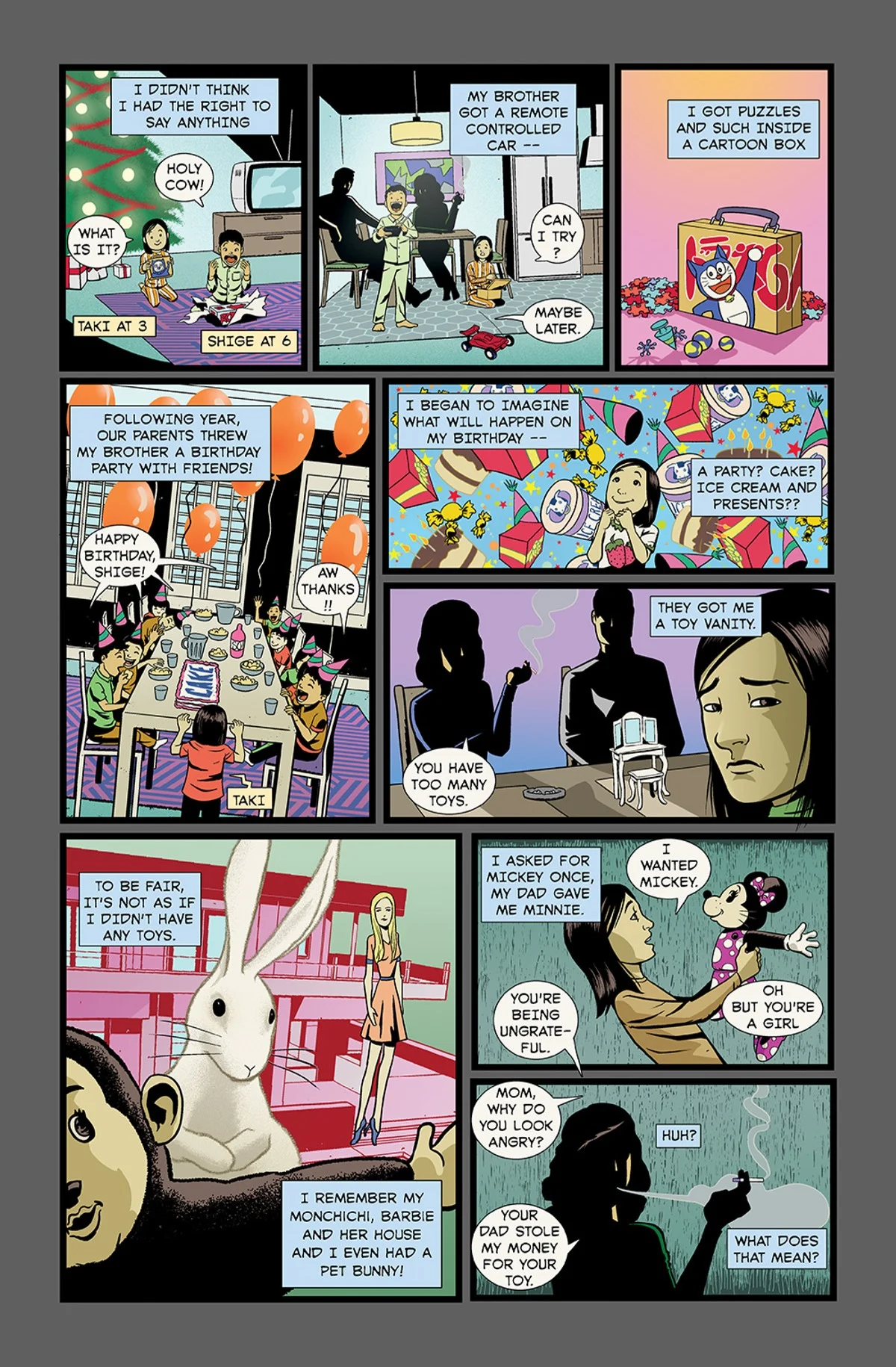

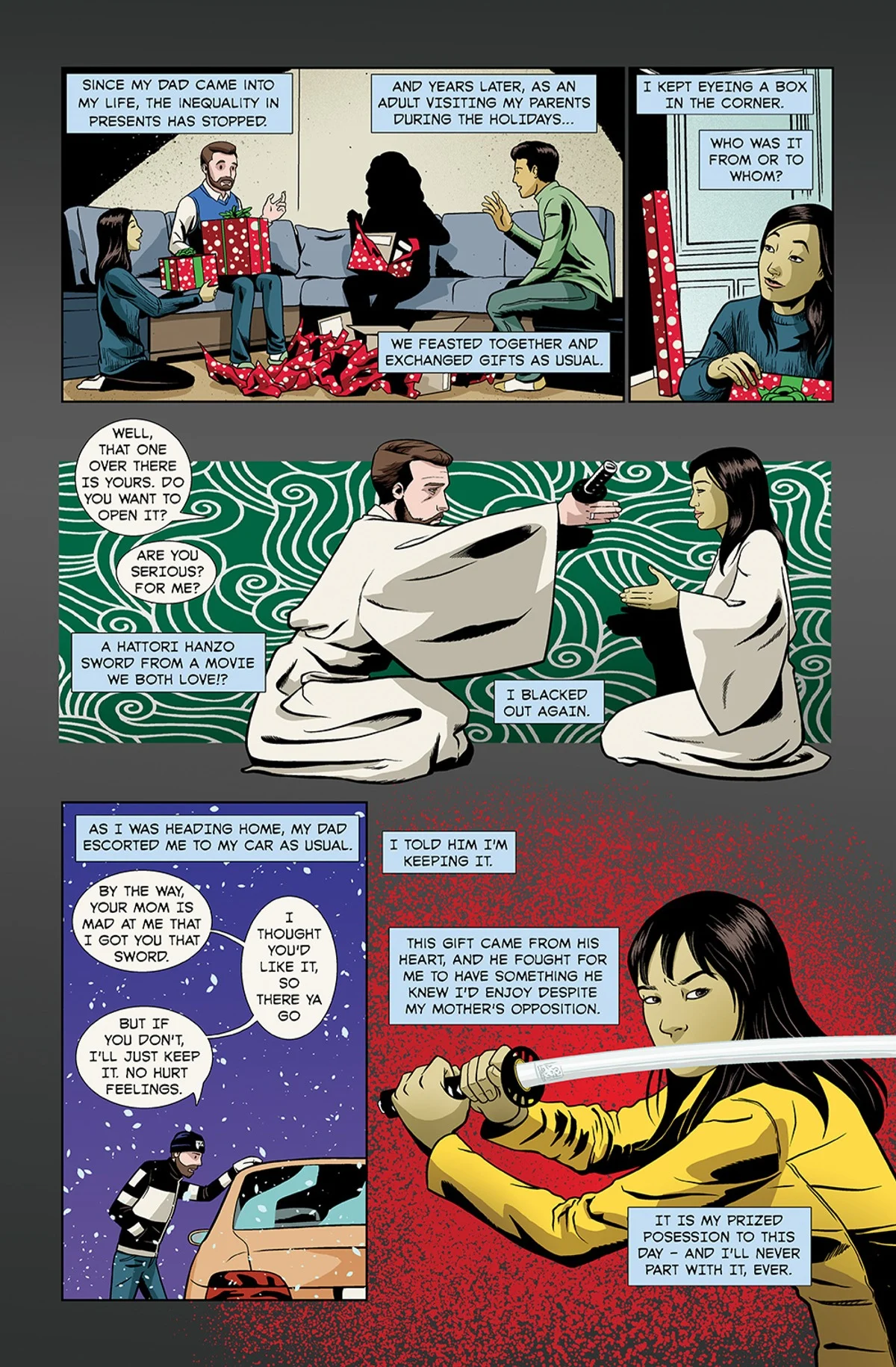

The comic “Toys” is “probably my favorite”, says Taki. The four pager delves into how Taki and her older brother Shige received unequal presents and, in turn, treatment, growing up. While Shige was thrown a birthday party one year, Taki was told “You have too many toys.” The chapter explores how historic gendered stereotypes detrimentally affect young girls growing up, causing them to feel inferior in comparison to male counterparts. Thankfully in this story however, “Toys” has a happy ending. Taki is gifted a prized possession—a Hattori Hanzo toy sword—which brings her validation after years of feeling second best. “I still have it,” she says, “it means a lot to me. It was a very cathartic moment to draw.”

For Taki, making comics is therapeutic. An accessible medium that almost anyone from anywhere can try their hand at, they’re also cost-effective, with just a few materials needed, and Taki found a safe space in the visual storytelling of pen meets paper (albeit digitally). The unique blend of image and text support one another to create a multi-dimensional narrative that pulls the reader viscerally into Taki’s life.

It wasn’t until her late 20s that Taki started to pursue comics. Now in her mid 40s, she’s perfected the art, having looked to “a giant list of artists” including Mike Mueller, Steve Rude, Mike Allred and Michael Oeming. Prior to her 20s, Taki primarily expressed herself through painting. She went down the advertising avenue, enrolling in art school, where someone pointed out: “You don’t want to be here. You should be doing comics.” It’s a memorable moment for Taki: “I really think about that all the time,” she says. Later that day, she dropped out.

At first, she was more interested in expressing herself through the analogue, describing herself as a “hands-on” artist. Years later, working digitally was unexpectedly thrust upon her. “It’s definitely not something that I love and it wasn’t my first plan,” she says. “But going digital was essential because of the disease I have, multiple sclerosis.” Working digitally had its downsides, as the almost infinite ability to zoom in on an artwork meant she was constantly striving for perfection in the details, an impossible task given the fact that, as she says, “perfection doesn’t exist.”

It wasn’t the kind of pain that I actually wanted to let go. I wanted to remember it, I wanted to process it.

Taki took on all aspects of the comic’s creation process herself, from storyboarding to writing and coloring and also the lettering, which was the most challenging part for her. “Boy I would love to have some time to do everything again because I’ve learned so much just from working on this comic,” she says. Self-criticality is quotidien to artists, but in this instance, refreshing honesty goes hand in hand with the revealing nature of “Sleeping While Standing,”a comic which lays its soul on the page bearing candid insight into the inner workings of an artist digging deep into her past.

Taki’s comics stand out for their raw emotion. And that is the key takeaway from “Sleeping While Standing.” “It’s not easy,” she finally goes on to say, “it’s scary to welcome those feelings because they’re negative for a reason. But I think those feelings are also there for a reason. They need to be dealt with. And if you approach it in a way that’s about archiving and accepting, they’ll be satisfied. Make room for negative feelings in your heart, and they become a part of you that isn’t always trying to fight you. But you have to get to that point first.”

Purchase Sleeping While Standing on Avery Hill Publishing.