Having spent part of her adult life in Cuba, photographer Sophie Wedgwood couldn’t begin to count the times she’d had a drink at Hotel Inglaterra, the oldest place to stay still in operation on the island. But the air of suspense that enveloped the property when she visited again last year prompted her to point her camera at the people around her to immortalize its seductive “transience.” Wedgwood tells Gilda Bruno about how a whole new series came to be that night, and what the half-seen faces portrayed in it can show us about the importance of leaving room for wonder.

Hotel Inglaterra, the colonial-style building where photographer Sophie Wedgwood’s latest story is set, which was captured over the course of a single day last year, was erected in Paseo del Prado, the beating heart of Cuba’s Havana, in 1875. The longest-standing stay on the Latin American island, in its 150-year activity—66 since the then-Prime Minister Fidel Castro nationalized it—it welcomed everyone: “locals, diplomats, and tourists,” Wedgwood says, adding that it’s where she feels “most embedded” in the spirit of the city. It isn’t a coincidence that the hotel is just as widely populated even today.

There’s something hypnotizing about sitting in a chair where someone else sat decades ago, doing the same thing as them—observing

“There’s something hypnotizing about sitting in a chair where someone else sat decades ago, doing the same thing as them—observing,” Wedgwood says, explaining that her most recent body of work was crafted from the perspective of “a casual onlooker.” The once glorious and now slightly decadent stucco, chandeliers and plant-filled colonnades of the property lend themselves to that naturally. “Hotel Inglaterra is like a theater: full of villains and heroes, and the people in between,” she adds. “It’s like entering a scene that’s been flickering, looping, for decades.”

From the 22 dramatically contrasted, black-and-white photographs grouped under the title “Hotel Inglaterra,” the snapshot Wedgwood feels renders the day-to-day reality of Cuba best portrays a middle-aged concierge. Dressed in a double-breasted suit and matching hat in what looks like the hottest hour of the day, he leans against one of the Corinthian marble pillars of its exterior, catching his breath and shrugging his shoulders at a person out of frame—embracing his fate. “He’s waiting for something,” she says. “And it’s in those gaps, in that state of in-betweenness, that the most interesting moments happen.”

That the name of the hotel references her home, England, while being rooted in the history of Cuba, where part of her family is based and she herself has been for long periods of time in the past, is rather fitting. “Hotel Inglaterra” isn’t a factual retelling of the Caribbean island as it stands today, but instead conjures “what it’s like to find yourself at some forgotten outpost while the world moves slowly past you,” Wedgwood explains.

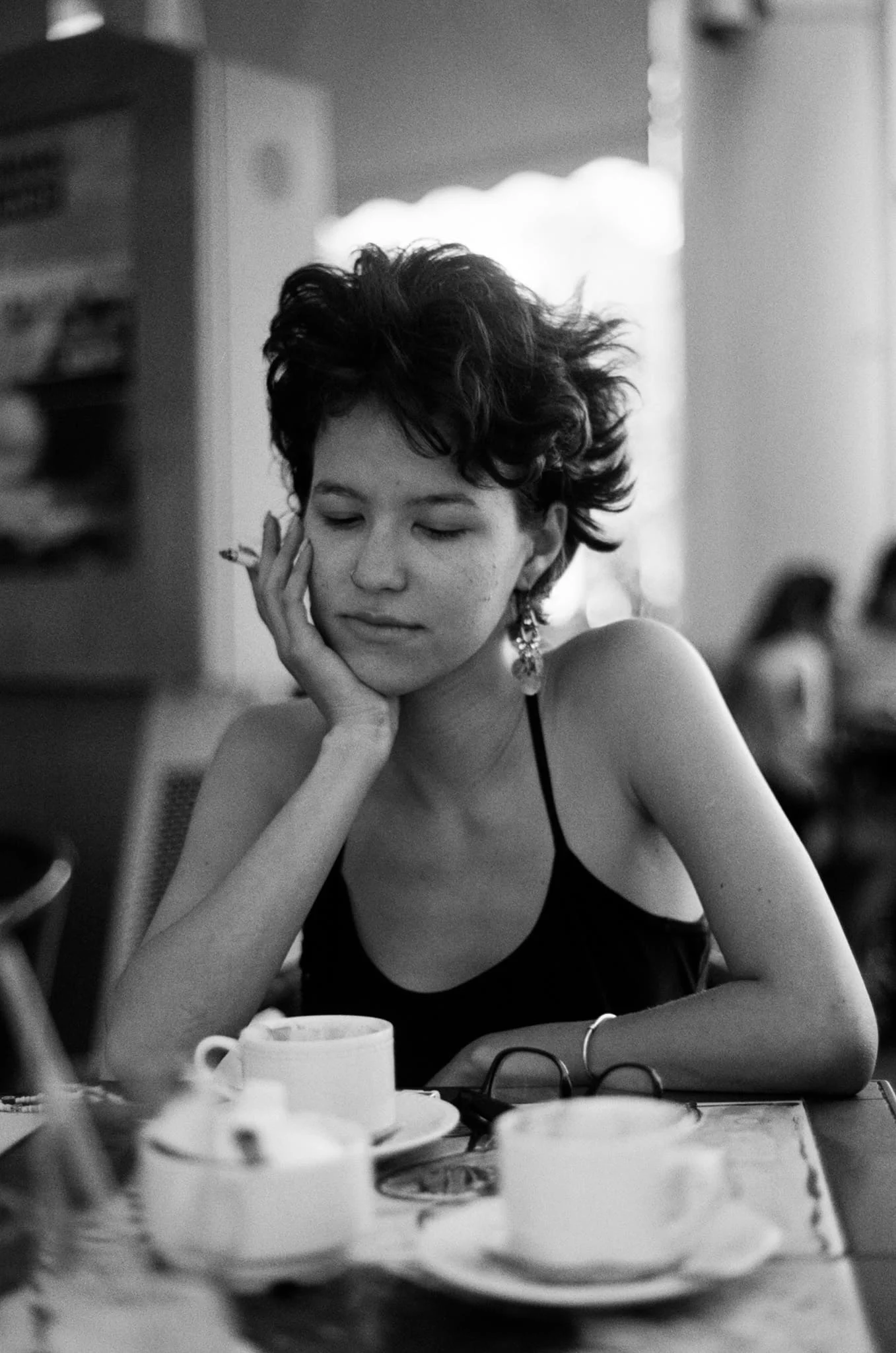

The strangers lensed in it—from the nonchalantly beautiful young girl, caught smoking with her eyes closed, head resting on her chin, who leaves us dying to hear about her daydreams, to the barely recognizable silhouette of man, his crisp, blacked-out body centered in a sun-soaked square immortalized from high above as the shadows cast from the palm trees growing tall all around him appear like specters chasing him down the street—conceal as much about the condition they are in, their routine around town, as they do about Wedgwood’s inner self. The relationships she forms with the space and the people around her, and the attentive curiosity through which she turns a seemingly banal action into a tale worth recounting.

A fresh-faced man serves hot churros at a food stall; a taxi driver at the wheel of a shiny, mid-century Ford Victoria glances at his back, a forlorn expression surfacing on his face as sunshine touches his wavy, coiffured hair and forehead. Who are these people? Do they know each other, do they not? Did they just happen to be there, to pass by? Or are they seasoned veterans of the Hotel Inglaterra, hanging out around it most days and nights?

It’s in those gaps, in that state of in-betweenness, that the most interesting moments happen.

Seen in succession, Wedgwood’s images look like grainy stills from a noir movie you can’t quite place on a timeline. The hotel’s half-lit neon sign flashes intermittently on the hotel’s left-hand side as the aridness of Havana’s late afternoons gives way to sticky downpours, intoxicating cabaret scenes and more mischief from golden hour into sunrise.

Wedgwood portrays the anonymous residents and the curious who gather around it, creating a world akin to a Wong Kar Wai film where apparently unrelated characters meet over dialogues that perplex, morph and return, and romances unfold across fleeting looks and confessions barely spoken; words left untold. Wedgwood is drawn to these nonlinear, fragmented narratives, describing “Hotel Inglaterra” as “a loose constellation of blurred characters: faces half-seen, moments that feel both cinematic and transcendent in time.”

Photography, for her, is “a way to examine how reality and memory twist around each other,” and sometimes even intertwine. It is also an outlet to cultivate the fantasy that, she feels, is lacking in contemporary work. “There’s so little mystery left in people these days,” she says, referring to how social media grants us “instant access to perfectly curated lives,” leaving little room for wonder. The people she photographed in Cuba, on the other hand, “still possess that rare sense of intrigue, that quiet unknowability which we’re rapidly losing,” she explains. The resulting series seeks to prove that “if the world itself does not have a coherent structure, it’s unreasonable to expect art to have one”.

Perfectly imperfect at that unrepeatable moment in time, the protagonists at the heart of “Hotel Inglaterra” appear like visions in dreams—flashing before your eyes. Passing embodiments of a city that “holds onto the past tightly, but is changing faster than it’s ever done before.” As Wedgwood says, the project is meant to make you feel like you’re spending “the night before a hurricane in a hotel on an island under embargo in the middle of the sea,” with tobacco smoke and indistinct chatter slowly absorbing you in its lobbies.