The relationship between an artist and their art is not always straightforward. How far should we take into account someone’s biography when we look at their creations? How directly can we connect the life and the work?

Corita Kent (1918 – 1986) was a nun, an artist and an activist whose beautiful prints bring together spirituality and symbolism.

Born in Iowa, her family later moved to California and Corita (born Frances) joined the religious order Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles when she was 18. This was a progressive and outward-looking community which attracted creative heavyweights such as Alfred Hitchcock, Saul Bass and the Eames.

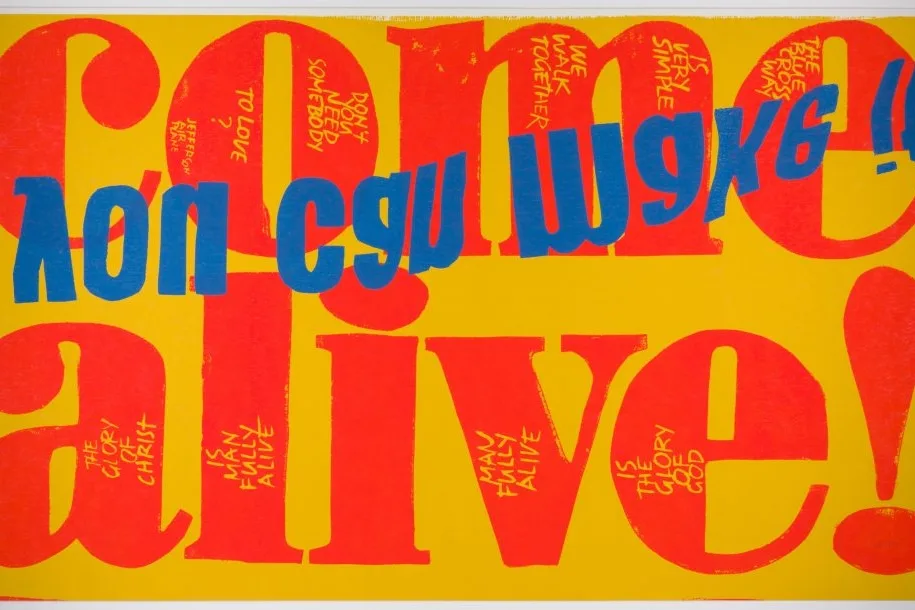

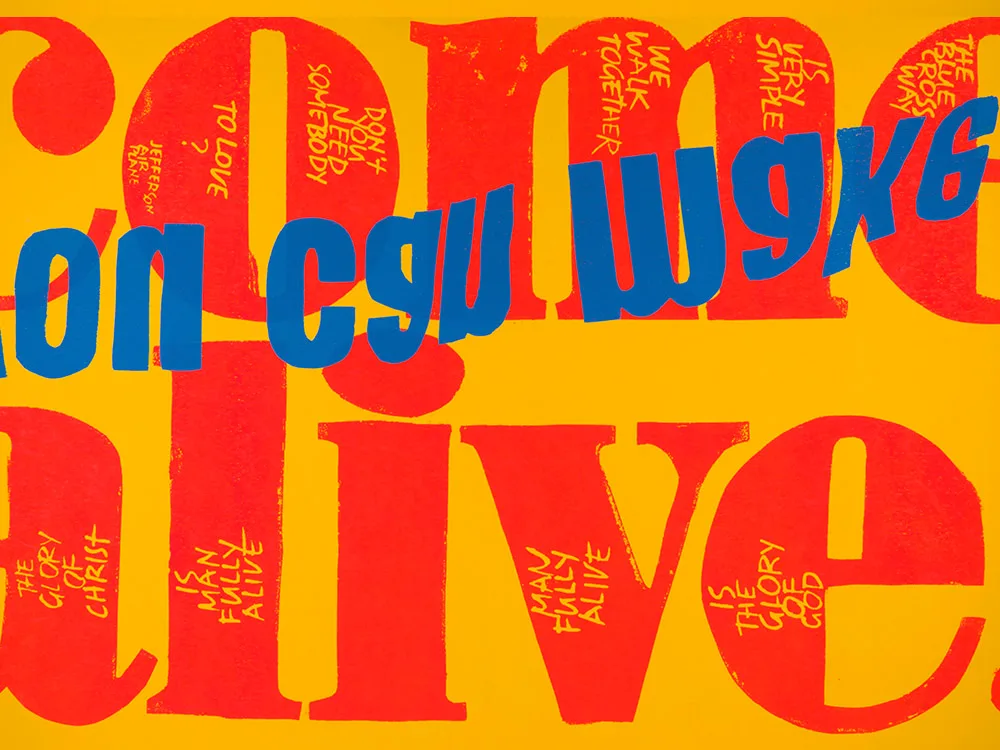

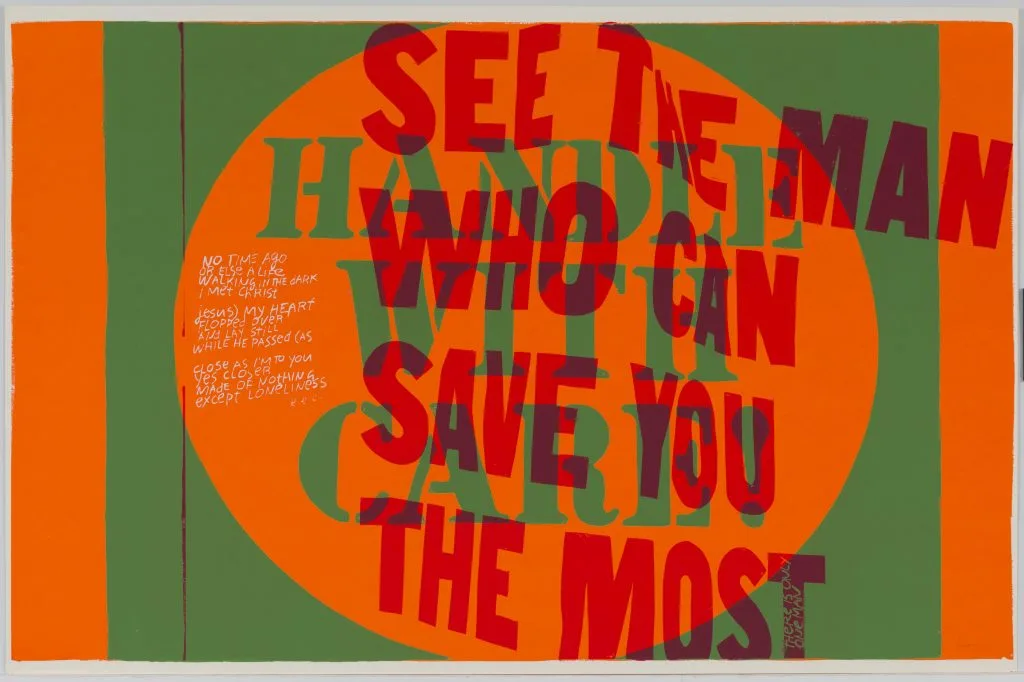

After being encouraged to move into teaching, she taught herself silkscreen printing on a DIY kit. She started off making figurative work until concerns raised by some of her religious colleagues steered her work in more of a Pop Art direction.

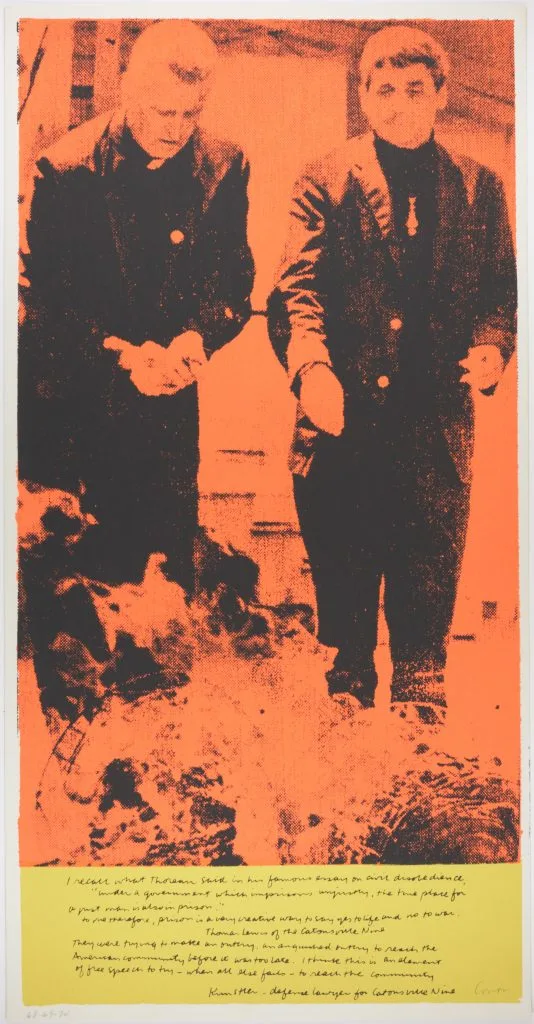

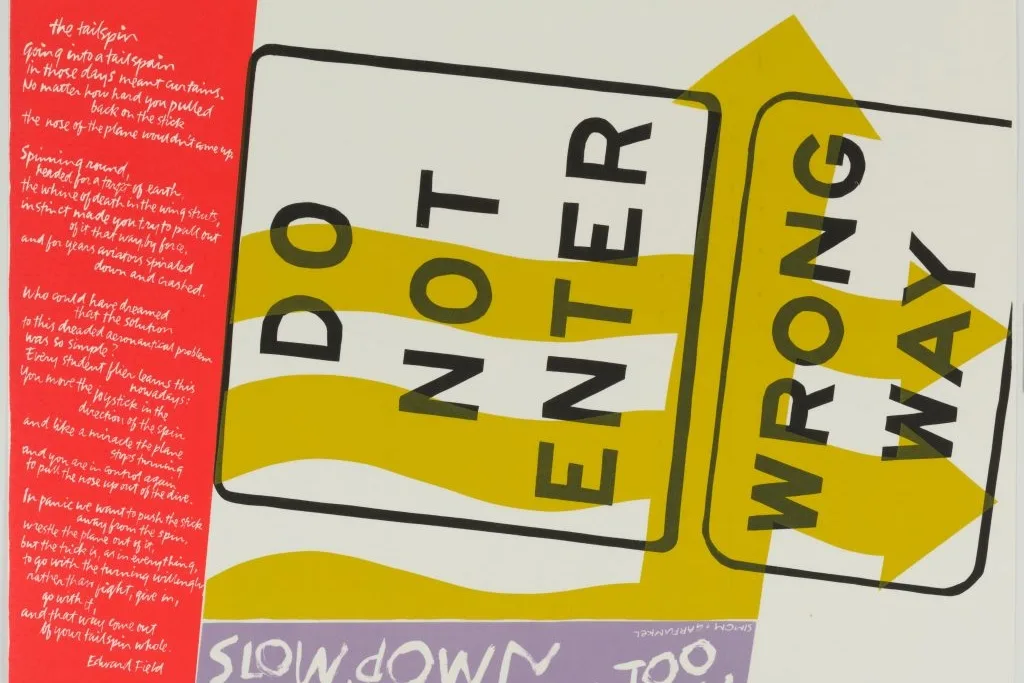

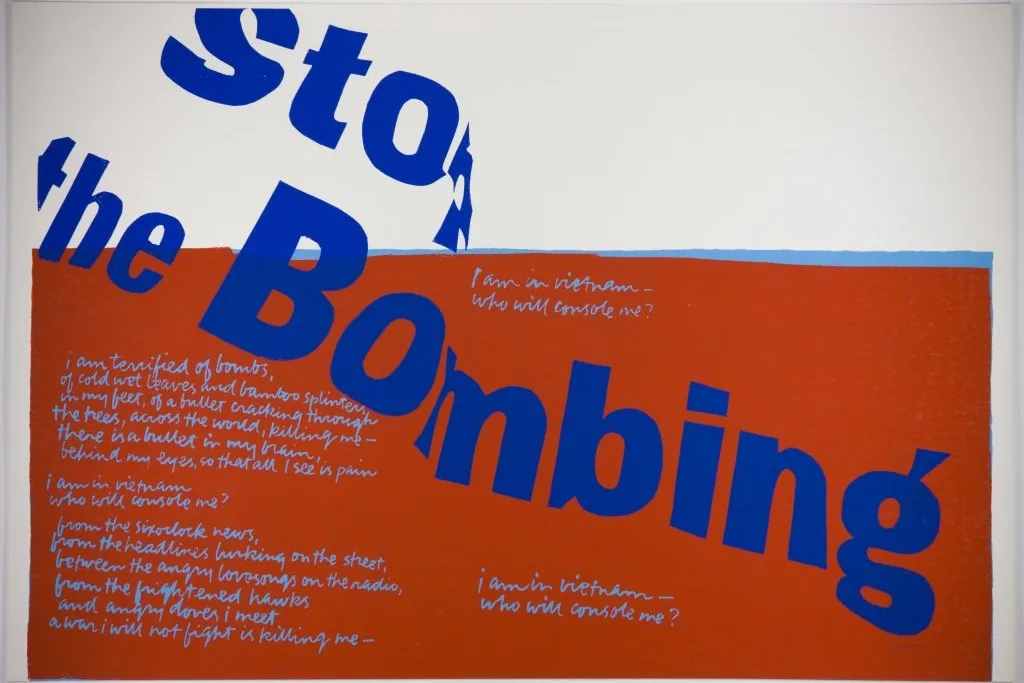

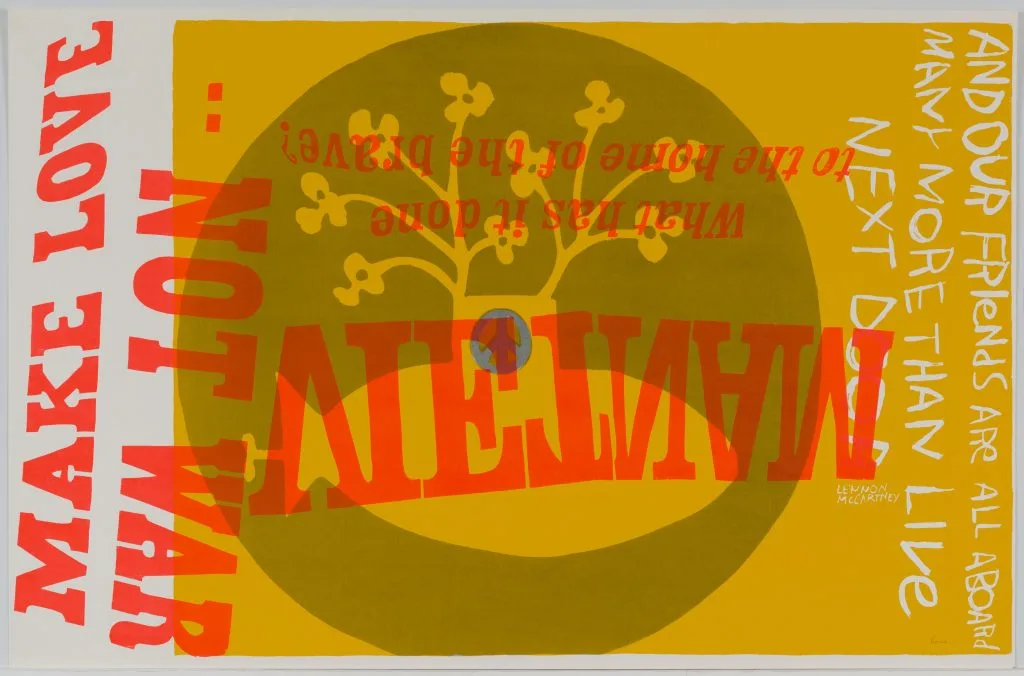

Her work is a febrile mix of text, image and symbolism that took on the biggest issues facing America – poverty, racism and the Vietnam War. In 1968, the watershed year when the 60s seemed to come to the boil, she left religious orders but still the narrative of the artist-nun persists.

“Though she was very active in the art world of her day, as a nun Sister Corita Kent was immersed in a different kind of community,” says Cynthia Burlingham, director of the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts which now houses Corita’s archives.

“I also think it’s likely that she was overshadowed because she was a printmaker in an era when the highest profile contemporary prints were being made by well-known painters working with prominent print publishers such as Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles and U.L.A.E. in New York.”

But if she was overshadowed or under-appreciated in her own time, since her death there has been a renewed appreciation for both her aesthetic talents and her ambition for art as a means of tackling big, complex issues. Cynthia thinks this “definitely” takes on particular resonance in 2017 when creatives (especially in the US) seem as alive as ever to social and political issues.

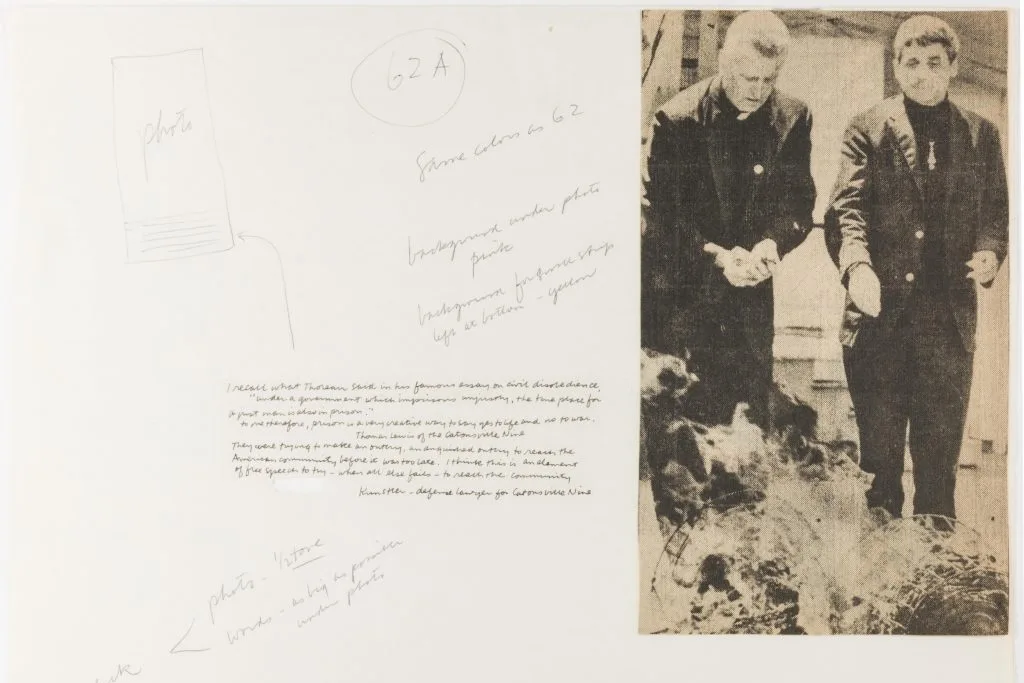

The Grunwald Center (part of the UCLA’s Hammer Museum) has 1,400 objects in its Corita Kent collection, from published silkscreens to drawings, color studies and even magazine clippings. Together it provides a fascinating insight into the way Corita Kent worked.

Going through the various objects in preparation for the recent launch of the online archive, Cynthia and her team were struck by Corita’s dedication to the particular craft of printmaking.

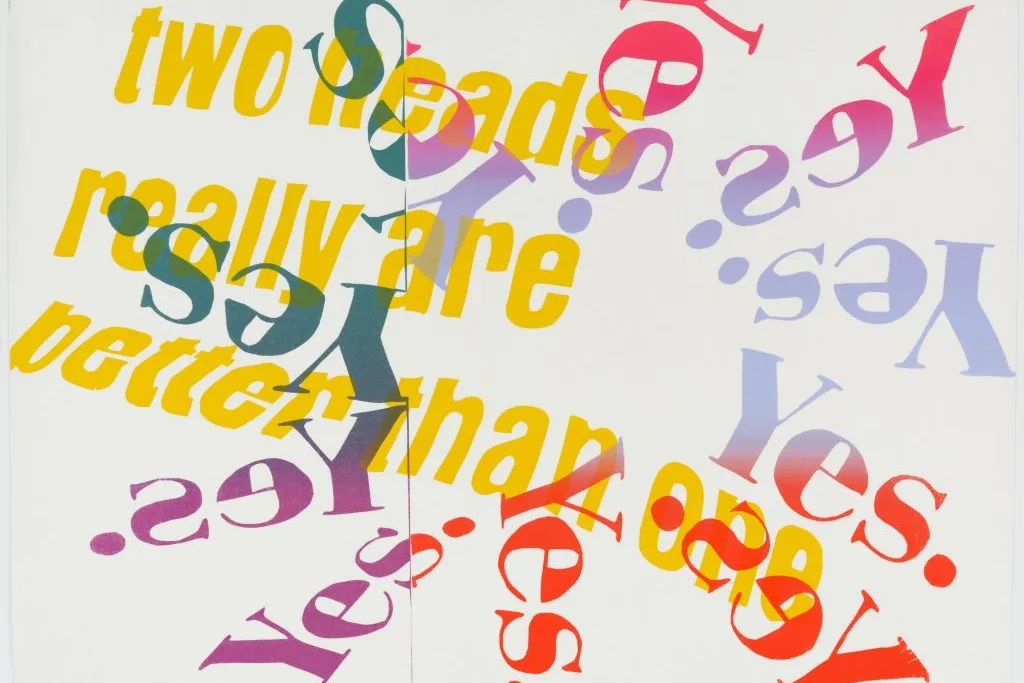

“One of the things I find most interesting about her work is how committed she was to the medium of printmaking as a way of communicating her progressive and democratic ideals.

“She made large numbers of prints, generally not in limited editions, as a way of making them available to all. When she originally donated the archive in 1986, we were all delighted to discover it contained her entire personal archive of prints, virtually every print she ever created, as well as many unknown and unpublished preparatory works.

“It was such a profound gesture to entrust this archive to a museum and a university also committed to democratic ideals and breaking down barriers to accessing art, and we strive to honor her gift and contribution today.”