Varanasi, a city in North India running along the banks of the mighty Ganga river, can feel like a spectre from the past. One of the world’s oldest continually inhabited cities, it’s often considered the spiritual capital of the country, and had always seemed mystical to photographer Shashank Verma, who set out to capture life there. He tells writer Ritupriya Basu about a set of letters that inspired the journey, and the stories of the city’s people who have resisted the onslaught of colonization, and have continued to celebrate their cultural legacy.

It all started with a few letters. Every time photographer Shashank Verma visited his home in Mumbai, he loved to rummage through old archives and photobooks safely tucked in the family ‘almari’ (cupboard). On one such visit, he found a box of developed negatives and letters from his grandmother—addressed to his mother—detailing her life in the city of Varanasi, also known as Banaras. These letters stirred Verma’s already growing interest in the city.

“The letters spoke about her neighbours, their everyday life, the iconic ‘Ganga Aarti’ (a ritual where candles and flowers are floated down the river) every evening, the boatmen on the river and the chaotic streets of Banaras,” he remembers. “These nuances shifted my perception about Varanasi beyond its reputation as the ‘spiritual capital of the world’.” Verma was inspired to see the city in a new light.

Running along the banks of the Ganga river, Varanasi is steeped in history. Over centuries, it has held on to its identity as a nucleus of spirituality, arts and craftsmanship, and yet changed in innumerable ways. It has survived the onslaught of colonization, and the waves of globalization that have swept through it, transforming into a place that’s at once tied to the past and the present.

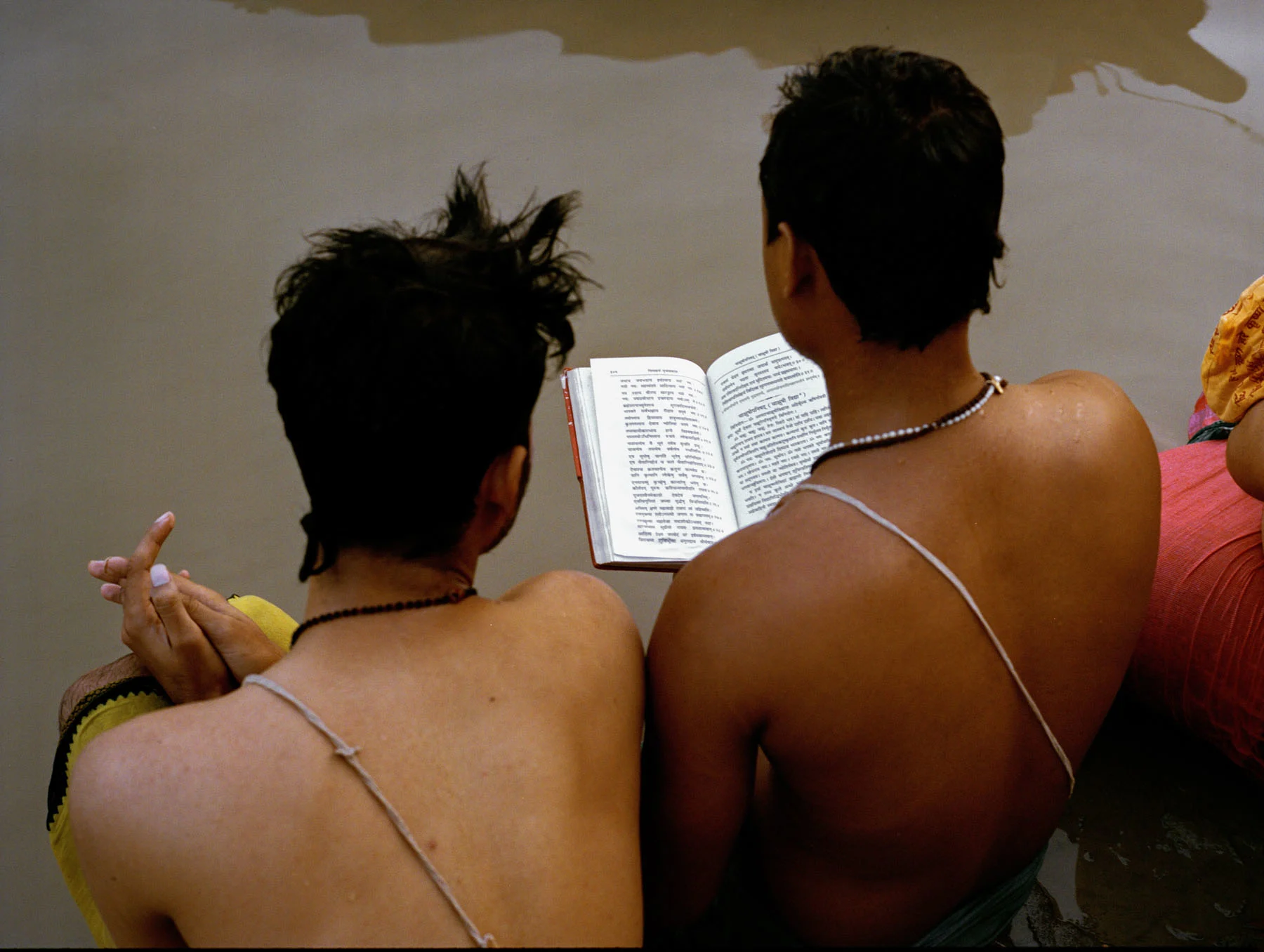

The same can be said about its native communities, who take center stage in Verma’s photo essay, “Traces of Survivance.” This subtle dance of life between the city and its people shines through Verma’s photographs, which capture snatches of city life—a boat full of people on their way to somewhere; two men engrossed in a conversation by the river bank.

Varanasi has witnessed conquests, cultural shifts and the march of time, yet it persists as a living testament to the tenacity of its people.

Verma came across the idea of “survivance”—a concept introduced by Gerald Vizenor, a Native American writer, scholar and literary critic—while reading an article. “As a term, it expresses the enduring vitality and resistance of Indigenous peoples in the face of historical trauma, colonization, and cultural erasure. It goes beyond the notion of mere survival; it emphasizes the dynamic, creative, and affirmative aspects of native existence,” says Verma.

“It seemed relevant in the spectrum of Varanasi’s history,” he adds. Varanasi, like the Indigenous communities Vizenor speaks of, embodies a narrative that goes beyond the challenges it has faced, embracing a dynamic and ever-evolving cultural identity. “The historical trajectory of Varanasi has witnessed conquests, cultural shifts and the march of time, yet it persists as a living testament to the tenacity of its people. This city, like the native cultures highlighted by Vizenor, has not merely survived; it has embraced a perpetual state of becoming.”

This tussle between the city’s historical roots and its contemporary identity is best felt through its people, who became a focal point for Verma. As he explored the city across two visits, he met people and families whose stories steered the course of the project. The encounters were endless—Verma met a family of weavers who migrated to Varanasi in 1937 from Kazakhstan. “They spoke of their family heritage of intricate weaving styles, their experience of losing their craft to the growing popularity of power looms, and now running a ‘paan’ shop (a small shop selling betel leaves and other tidbits) to make ends meet.”

Elsewhere, he met boatmen whose past generations had witnessed the British occupation. While many of their families were displaced with the ebb and flow of time, many working men still remain in Varanasi, unable to shrug off the feeling that they ‘belong’ on the river. And so, the city’s history remains entangled with its present, felt in the soul-stirring Hindustani music echoing through the streets, or the elaborate rituals that unfurl daily on the ghats—steps that lead to the river—which also became a central motif in the project.

On both his visits, Verma set out for a walk along the ghats at the crack of dawn, witnessing the city coming to life. He fell into a daily rhythm for about a week, observing and striking conversations with people, without taking a single photo. “It made me nervous at the start, but I wanted to immerse myself into the cultural space,” he says. As the days went by, he observed the life on the ghats bursting into activity every morning. “One such morning, on Dashashwamedh ghat, I was amazed to see the number of people waiting to shave their heads before starting their prayers (a ritual called ‘mundan’). It was a scene straight from Satyajit Ray’s ‘Aparajito’,” he says. Offering hair to God is a very common practice amongst Hindu devotees, especially at a holy place like Banaras. Hair is seen as a matter of pride and arrogance, thus it is believed that shaving off one’s hair is a symbol of gratitude and devotion to the lord.

Eventually, the deepening conversations lead to a set of portraits within the project, that sit alongside the landscapes and the shots of the city life, adding a layer of poignancy to the work. “The people I met and took portraits of,” he says, “in essence, became the living links bridging the narratives of the colonial past and the realities of contemporary India, particularly within the historical context of Varanasi.”