From Mexico City’s dance floors and shimmering lights to MoMA’s walls, Sandra Blow celebrates her queer community from within. Having grown up in a suburb around conservative beliefs, moving to Mexico City marked a rebirth for her, and led her to meet the chosen family she found refuge in. Her images of that chosen family are defined by glamour, surrealism and grit, but above all, a deep-rooted love for her subjects. Now celebrating 15 years as a photographer, she tells Dalis Robinson how her camera allowed her to give them shelter and a space to be shown as they want to be, as well as preserving the memory of their impact on their communities.

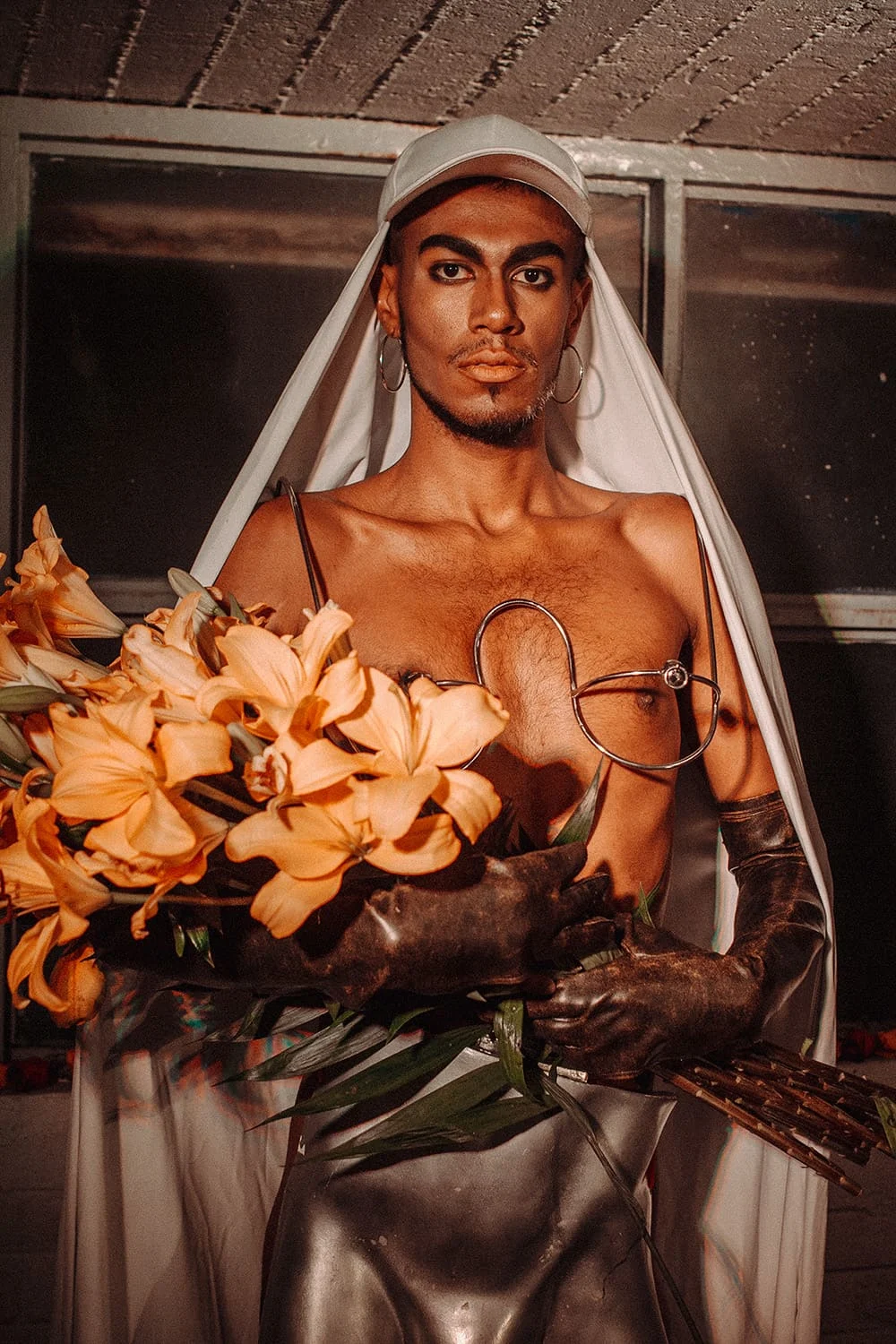

Over the last 15 years, self-proclaimed “glitter documentarian” Sandra Blow, from Atizapán de Zaragoza, Mexico, has captured images that are instantly palpable, never ornamental. Her work celebrates bodies and identities historically excluded from mainstream beauty narratives in Mexico: racialized, queer and marginalized individuals. Drawing inspiration from editorial fashion, she reimagines and reconstructs this aesthetic from the margins, finding glamour in a market stall, mischief on the dancefloor and tenderness in moments of intimacy.

I have always photographed from a place of profound love and respect… empathy matters.

As a queer person raised in a suburb outside Mexico City and faced with conservative beliefs and Catholic tradition, moving to the capital led her to start a new life. One full of drag queens, models, artists, free-thinkers and parties. Her perspective is one of belonging; she doesn’t observe from the outside, but creates from within. Her muses are her friends, fellow creatives and activist peers, giving her visual language a raw authenticity that’s emotional, political and powerfully honest.

Blow’s aim has always been to amplify the voices of those historically ignored and sidelined, including the LGBTQ+ community, sex workers, pornographers, strippers and elderly creatives. “I have always photographed from a place of profound love and respect. If I can do that for my community, why not? And even beyond my communities, I believe it’s important to support all non-normative identities. Empathy matters,” she says. “My gaze comes from admiration, love and friendship. And then, I see the causes I stand for and their meaning reflected in my photos.”

When asked if a specific moment led her to center individuals often excluded from the mainstream, Blow shakes her head. “No. I simply began taking portraits of my friends and my new life,” she says, “a new life I had never experienced. I was documenting how it all came to be. Including the ‘freaks’ like me, who became the chosen family I found refuge in.”

Her eyes fill with emotion as she speaks about those who have shaped her gaze. “Everyone in my photos is someone I love or have seen with love,” she says. “Whether it is love for how they express themselves or friendship. All of the portraits in the MoMA selection are of friends.” Blow goes on to say that her care also lies in the decision to preserve them in time and history by showing them as important characters.

Blow’s images offer shelter, allowing the people who made her vision possible to remain visible on their own terms. She fondly recalls Alan Balthazar, a late friend and creative. In life, Alan was an iconic figure of the then-emerging queer nightlife in Mexico City. Her passing marked the community, and Sandra, as Alan had been part of the crew she found refuge in. Present through the memory that Blow carries forward, at the opening of “Lines of Belonging” at MoMA, she thanked Alan for being present with her in spirit.

Everyone in my photos is someone I love or have seen with love, whether it is love for how they express themselves or friendship.

Affection is tangible in Sandra’s work. You can see it in her proximity to her subjects, and the way their bodies meet with light. With parties as her main focus, the joy now lives in the act of observing, timing and finding the angles that celebrate nightlife as a site of transformation. Recalling the nights that crawled under her skin, the photographer is transported back to a New Year’s Eve in downtown Mexico City at the former Hotel Virreyes, once a cultural hub for young artists. “It was New Year’s Eve, and I was walking into ‘El Festín’, the party I was working at that night,” Blow says. “My friend, Bruno, was at the door as host, wearing this jewel mask, lit by the tungsten spill of a streetlight. El Centro’s light at night is very red, yellow and orange. That’s why the photo breathes those tones.”

I simply began taking portraits of my friends and my new life... the chosen family I found refuge in.

Inside, the party teeters on the edge of a dream. The lights reveal performances all around: pearls pressing against corsets, fruit sweating on naked bodies spread like a feast on tables, and a stranger reading poems in French inside a bathroom stall. The evening is fabulous and tender, yet also full of melancholy. Sandra’s father is dying. A toxic relationship is unraveling. One of the dark stretches of her young life, with grief closing in, a relationship splintering. And still, the room swayed her. The party allowed her to escape her reality and create as her own alchemy.

“That night was surreal, between sad and beautiful. Every detail felt destined,” she says. “My reality was ugly at the time, but being there for the night let me create while I was hurting and gave that hurt somewhere to go.” That hurt was channeled into images that, years later, live on the walls of MoMA.

The path to this lifelong dream of exhibiting her work at one of the world’s most renowned cultural institutions was paved by taking portraits of her loved ones and glamorous strangers emerging from the shadows. Sandra’s works entering MoMA are what she considers largely archival: images from the “boom years” of CDMX parties. “Youth in ecstasy,” she calls it, smiling.

For Sandra, the point of showing the work at MOMA is not to swap one room for another, but to carry the same temperature into each: the heat of friendship and the resistance of the community that makes the pictures possible. If someone finds Sandra’s work and is inspired by it, what does she hope they borrow from it? Courage, she says. “The courage to fight for my dreams and not to give up, despite how difficult the art world can be. Especially in places where the odds are stacked against many of us. The road may be full of thorns, but the rose at the end is very worth it.”