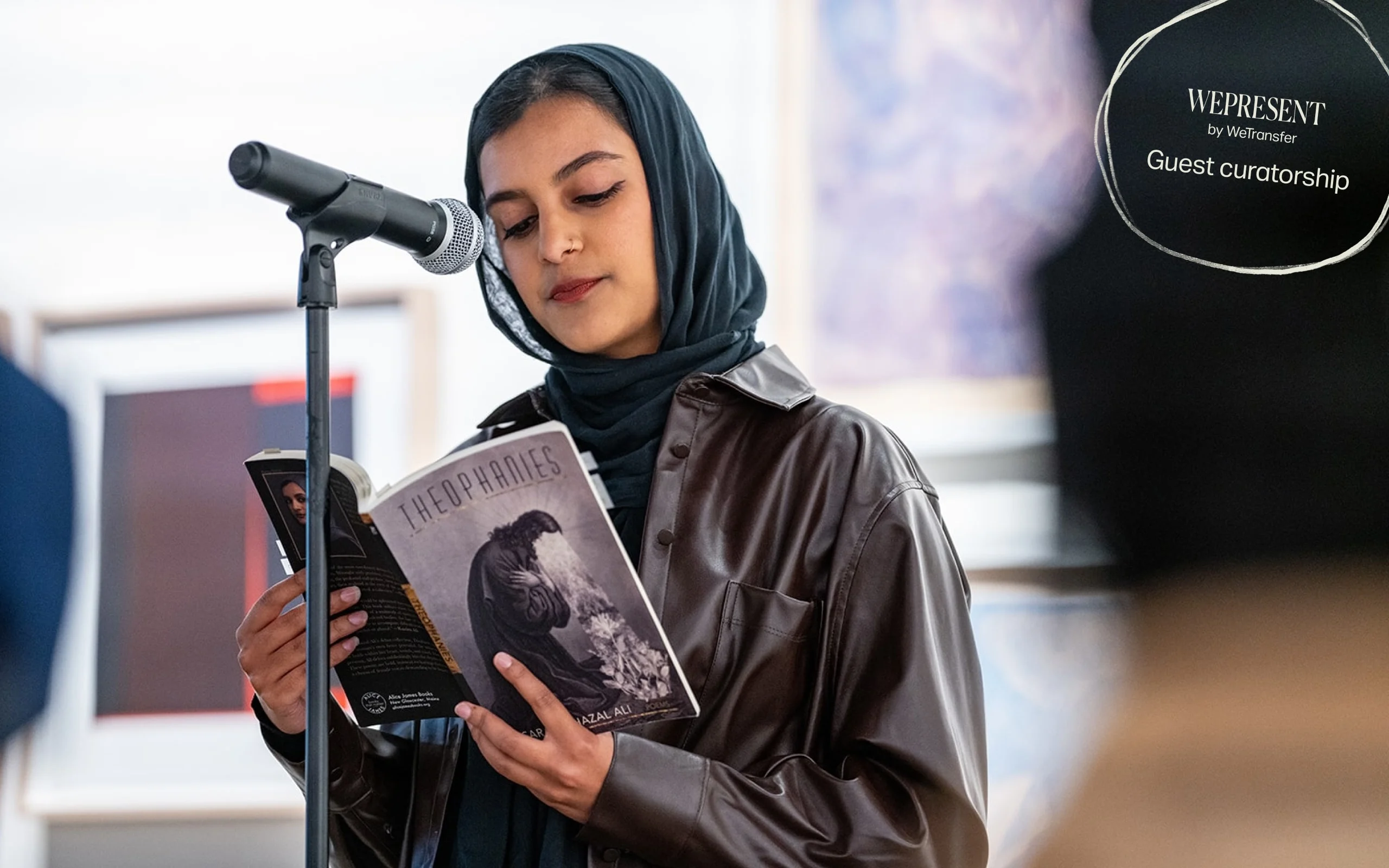

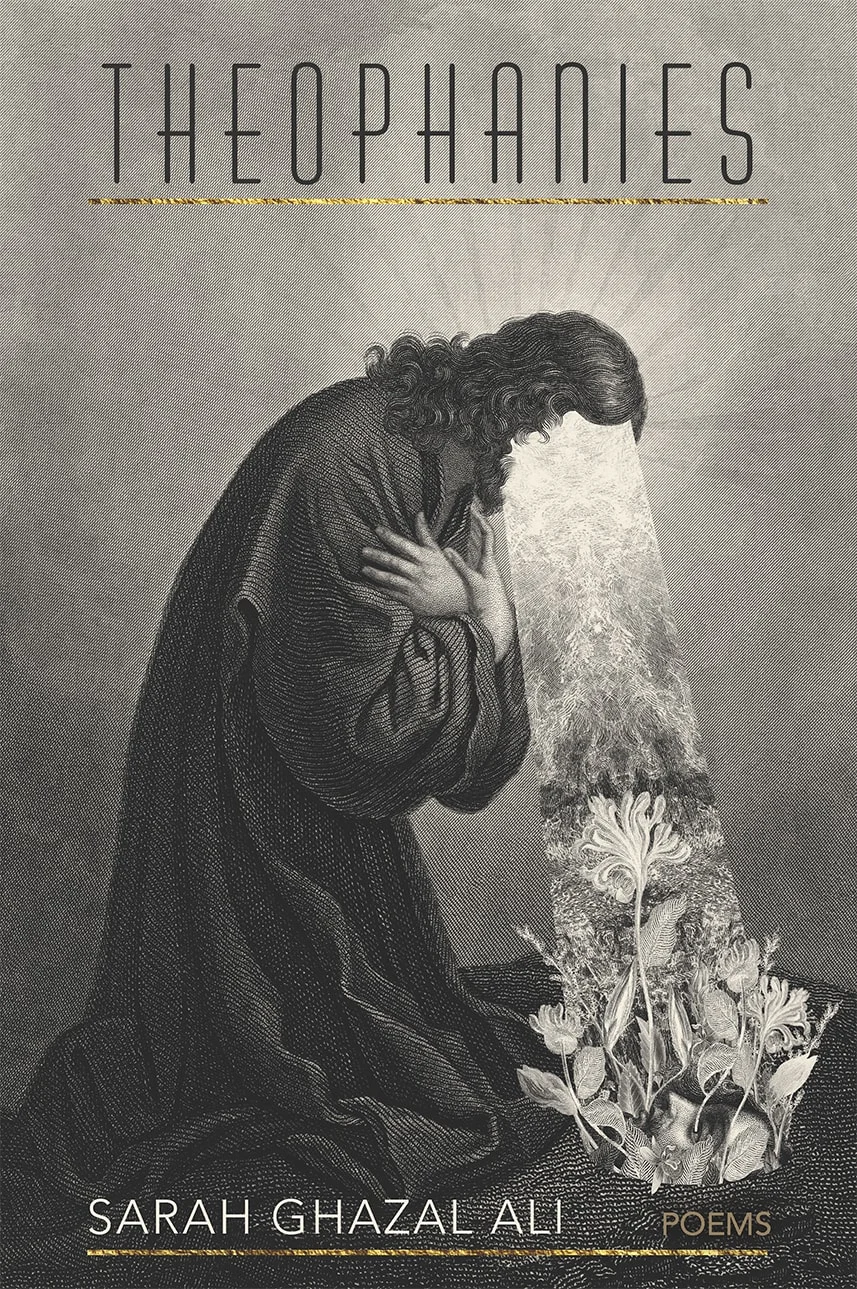

Sarah Ghazal Ali is the next artist that Riz Ahmed has chosen to highlight as part of his guest curatorship. The poet’s work, which draws from her faith, heritage and the complexity of womanhood, asks poignant and sometimes challenging questions about the world around her. “Sarah’s collection of poems in Theophanies weaves together faith, doubt, and the female body into a tight knot—one that lived in the pit of my stomach long after I had read it,” says Riz. “Reimagining tradition and devotion, she is both subverting and celebrating her rich and complex inheritance.” Here, Alix-Rose Cowie dives deeper into the work and mind of the rising poet.

Poet Sarah Ghazal Ali’s original plan was to become a lawyer. Early on in her political science studies she took a course on ancient political thought, and on the syllabus–alongside the likes of Plato and Aristotle—she was confused to see the Bible. The assignment was to read the book of Genesis and write an argument for or against Eve as a political agent in the Garden of Eden. She felt invigorated by the possibilities: “What else is there to say or to think about the other women? What else can I learn about their agency that isn't obvious because they're ancillary in these stories that are told about men?”

Her politics class fed into her creative writing classes, and she began writing poems about her namesake, the biblical figure of Sarah. Though she’s not named in it, Ali was familiar with Sarah’s story from the Qur’an, but she found that the Bible had additional details about the women from the versions she knew, and began to uncover a fuller picture of who they might’ve been. “I got obsessed with women's agency,” she says. “[Taking the course] really just blew the door down for me. It made me feel that I have permission to approach these matriarchs from a lens of curiosity.”

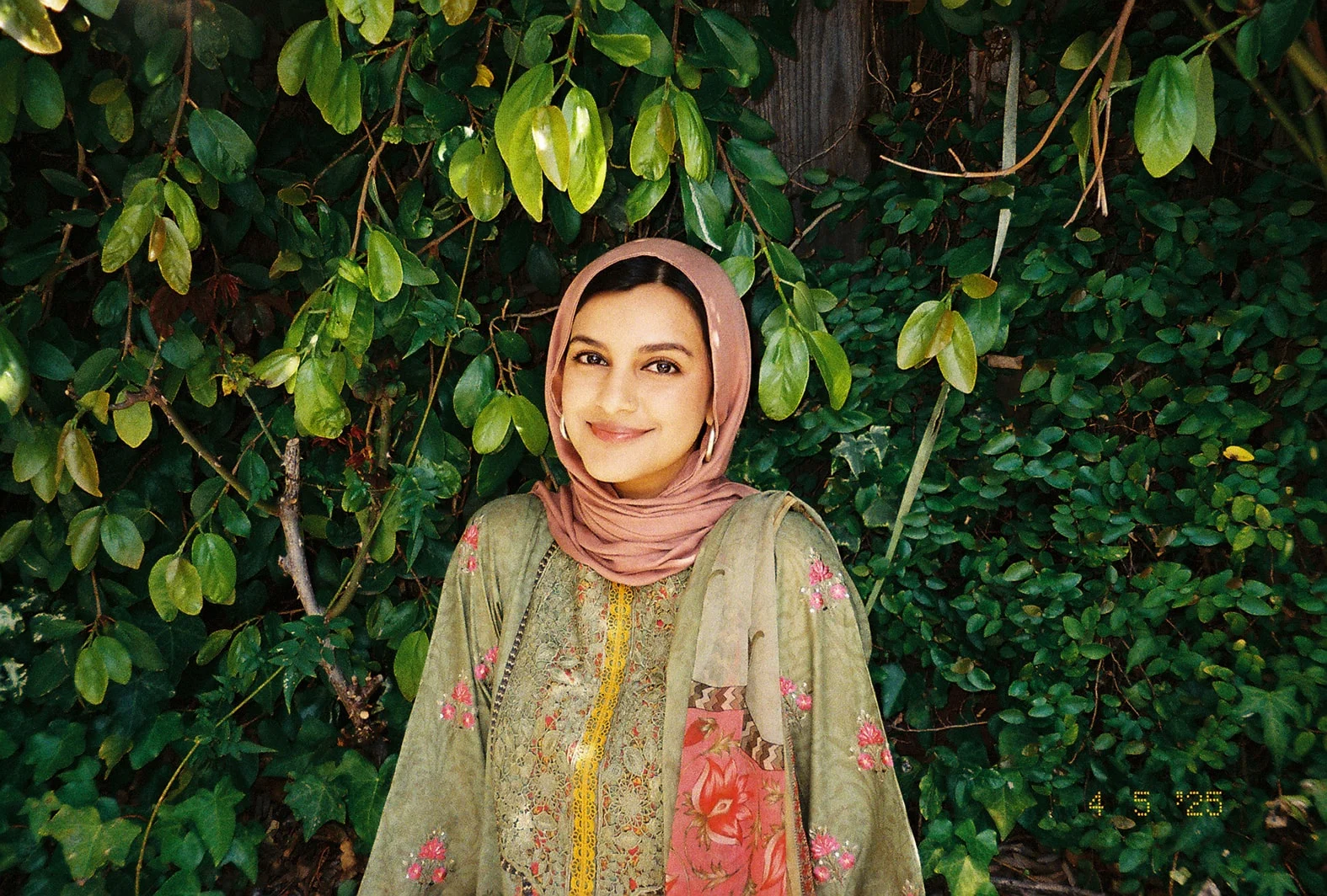

Ali was born in New York, her parents had moved to the US from Pakistan in the 1990s. After some time living in Chicago, and then Tennessee, her childhood was spent for the most part in Massachusetts on the East Coast, and her teenage years across the country in California. “Moving around that often and not feeling grounded in one place has definitely shaped me in a lot of ways,” she says. There was more uncertainty when it came to religion. Her parents are of two different sects of Islam: her mother is Sunni, her father is Shia, and both presented their versions to her as the correct choice. Instead though, she sought out her own religious education from a young age, figuring out for herself what it means to believe in something. “It helped me realize that you can go off of your intuition when it comes to faith. So much of faith can't be logical,” she says.

Her poem “Litany with Hair” begins:

and God said veil

said pull it over your breast

and mama said I miss it long

said wish you can grow it back

and baba said not explicit

said where does it say to?

To understand the Arabic texts in the Qur’an Ali would look up the translation for words one by one, often finding an array of different meanings depending on the context. “Instead of distressing me more, that actually gave me a lot of comfort and freedom. And I realized that it's all just about interpretation, and no one interpretation is necessarily better than another. The Qur’an is so layered and poetic itself,” she says. The ability to read things in myriad ways became a natural path to poetry where every word or line can sing entirely on its own, or change its tune by what comes before or after it, where the line breaks or runs on. “My faith informs the way I write poetry,” she says. “Religion is where I have a lot of questions, uncertainties and insecurities, even. But then poetry is where I go to privately wrestle with all of those. It's really where I think in layers and multitudes rather than just singularly.”

Theophanies (Alice James Books, 2024) is Ali’s first published collection of poetry. She wrote it to make sense of her fears, hopes, desires. “I wanted to make them legible to me,” she says. But as she pulled the collection together, she saw that while she wrote the poems for herself, she created the book for others. “As a young person I read a lot of books about Muslim women but I didn’t see my particular quandaries and quarrels reflected,” she says. She’d read the perspectives of people who had left the faith, seeing it through a particular feminist lens. “But that’s not the only feminism,” she says.

A line from the first poem in Theophanies “My Faith Gets Grime under Its Nails” reads:

My faith is feminine, breasted

and irregularly bleeding.

“I love my faith and I love being a woman of faith, but the world that I'm in does not love women and the world is so difficult for women. How do I navigate these two things together?,” she asks. “Writing the poems taught me that to ask questions of your faith, your culture, your loved ones, the world that you're in, and to demand that it be better, is a faith practice and is a labor of love.”

In Theophanies, Ali’s words are woven together with the strength and stretch required to carry its heavy themes: femicide, violence, motherhood, the expectations of daughterhood, sex, fertility, abortion, colonial and patriarchal legacy, the intimacies and intricacies of being a woman.

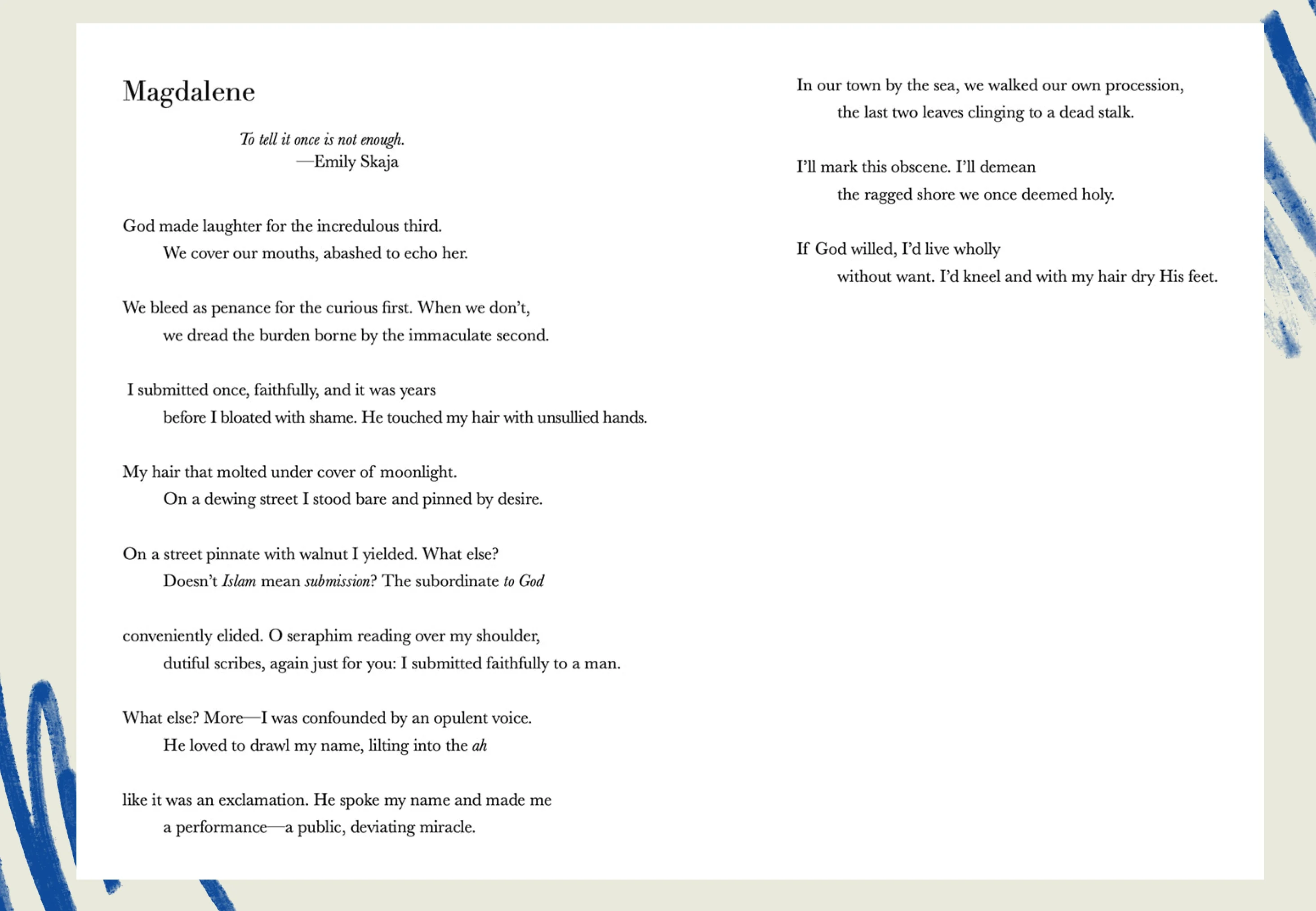

A line from “Magdalene” reads:

We bleed as penance for the curious first. When we don’t,

we dread the burden borne by the immaculate second.

As the reader it can be enticing to tie the author’s personhood to their poems. But Ali writes wearing various masks and personas: as different women from the Abrahamic scriptures, as variations of herself, as an imagined mouthpiece for God. She has mulled over how autobiographical poetry needs to be in order to be truthful and has found that leaning into fiction has made it easier to be vulnerable. It creates some distance between herself and the speaker of the poems. “I felt very comfortable inventing things for the sake of emotional truth, emotional clarity, and narrative clarity,” she says.

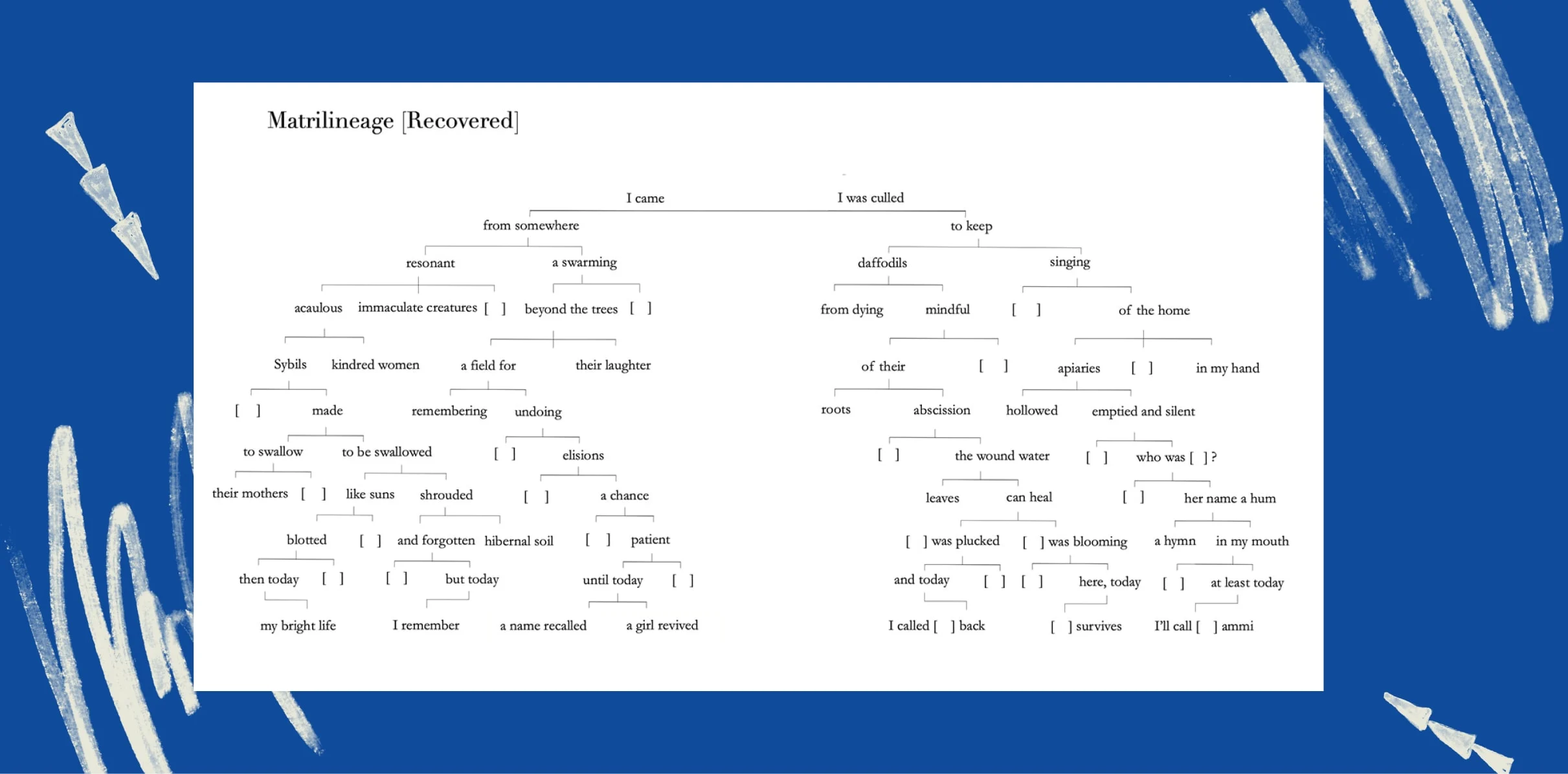

The dedication at the beginning of Theophanies reads: ‘For the mother line’. A number of poems reference the women who came before Ali, but perhaps none more than “Matrilineage [Recovered]”, an experiment in invented form that’s a symbolic rewriting of her family tree. When Ali was a teenager an aunt sent her a PDF of their family tree dating back to the time of the prophet Muhammad. Both of her grandmothers had passed away before she could know them, and ask about their families, while the violence of the 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan had also stolen pieces of family histories, leaving painful gaps. But when Ali opened the document, she was devastated to see that all the women’s names, including her mother’s and her own, had been redacted.

“It's a belief [in Islam] that women's names are part of their awrah, which is their most intimate parts, so only certain people should be able to access them,” Ali says. “But I didn’t know this at the time.” She did end up receiving a copy sent exclusively to the women in the family with all the names accounted for. But, Ali says, “in many places, or families, women's names don't matter at all.” Prompted by a writer’s residency call for works under the theme ‘Rebellious Joy’, she decided to reclaim the family tree as a poem in itself. The first two entries are: “I came” and “I was culled” asking herself at each branch: from where? for what?

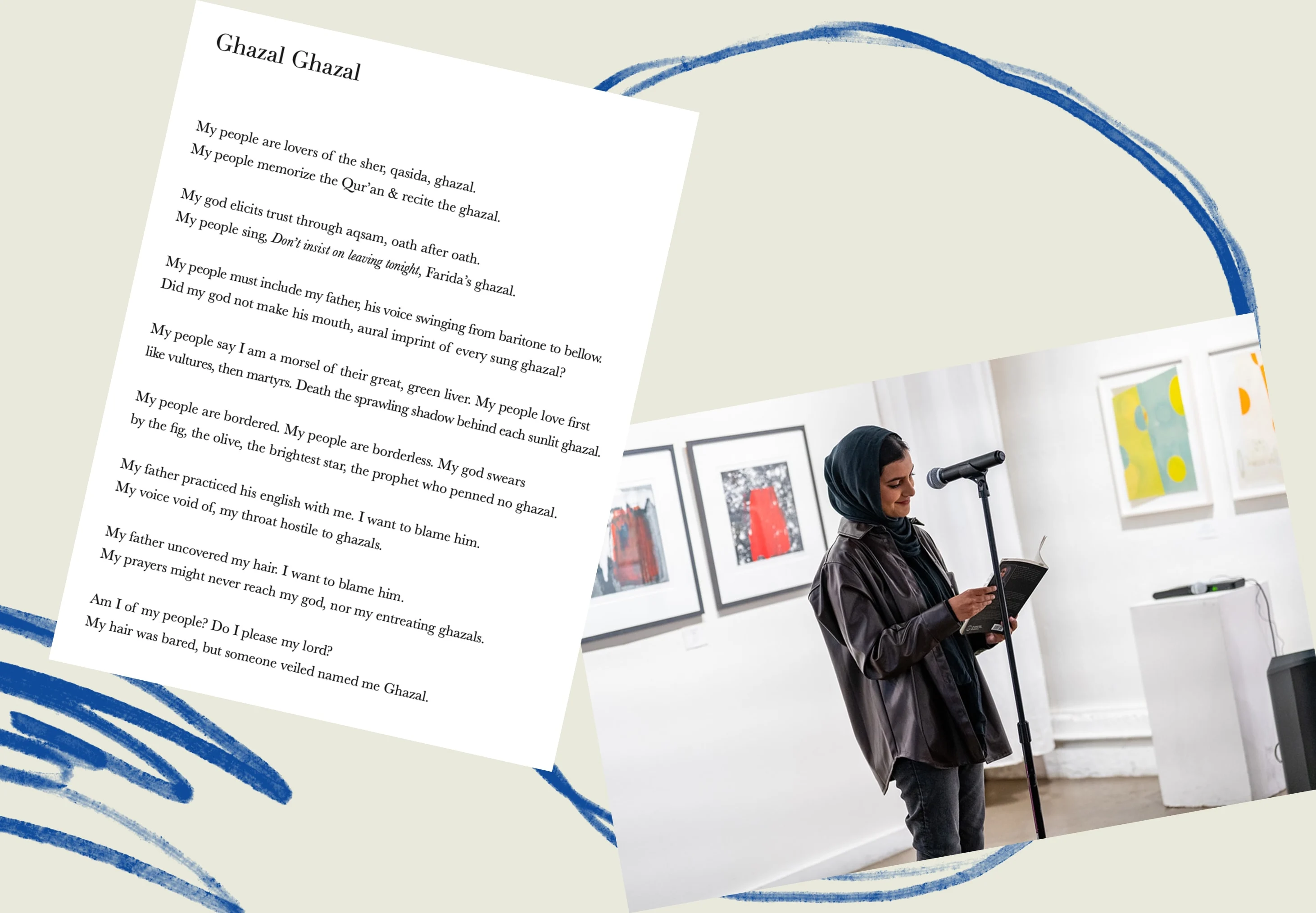

Sarah’s middle name, Ghazal, is a type of ancient Arabic or Persian poem. The form is prominent in Urdu too, Pakistan’s official language. Ghazal was given to Sarah by her parents before they could have known who she would be. A gift of predestination from the people who came before her and acknowledgement of the importance of a name. “I had no choice but to become a poet.”