When a tsunami destroyed the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station in 2011, the resulting radiation was so strong no one was allowed in. Japanese photographer Joe Nishizawa was granted rare access to capture the dismantling of the nuclear plant, and in doing so, is building a record for generations to come.

This story is part of Refocus, an initiative to showcase photographic talent from under-represented groups. This time we focus on age, to challenge an industry which too often prizes the newest and the youngest. We gave three grants to three photographers who've seen the industry change over the years, and whose talent is all the better for it. See the whole series here.

In 2011 a magnitude nine earthquake off the east coast of Japan triggered a tsunami which wreaked death and devastation in large parts of the country. At the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station it caused the greatest nuclear disaster since Chernobyl in 1986.

While many of the thousands of people evacuated from their nearby homes remain displaced, photographer Joe Nishizawa was granted rare access to the station to capture its crew, who are hard at work on the gradual task of safely dismantling the reactors. It’s a daunting job that’s said to take 30 to 40 years to complete.

“It’s not possible to complete the work during the time of my generation,” Joe says. “That’s why it’s our duty to do our best, with the utmost sincerity, before we pass this arduous task on to the next generation. In such a situation, to record it through photography is probably the only thing I can do.”

Joe first picked up a camera as a high school student in the 1980s. He’d shoot on black and white film, processing the images in a dark room. It was on the job at an advertising photo agency in the 1990s where he first became acquainted with digital cameras which were becoming popular at the time.

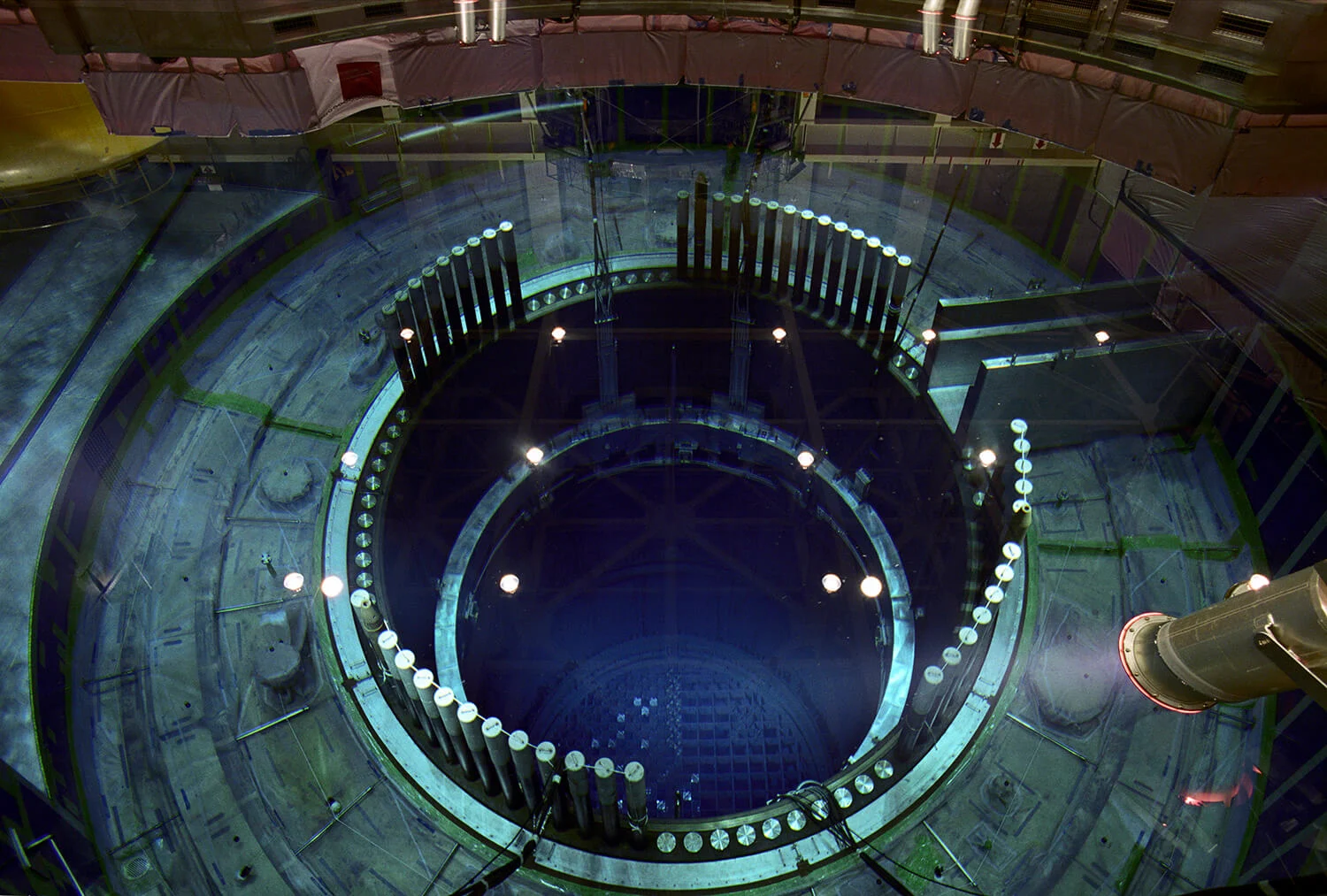

Interested in science, civil engineering and industry, his photographs give us backstage passes to what makes our modern world work. He shows us what’s lying beneath the tarmac and beyond restricted access. With his camera as a golden ticket he has ventured into underground expressways closed for construction, cavernous storm drains and grinding, metallic steelworks corporations to capture what he calls “functional beauty.”

He uses wide angle shots or a bird’s eye view to capture the great capacity of his subjects. “I became aware that I knew nothing of the industries which support our quotidian lives,” he says. “But I happened to have this mighty tool: photography. Every time I have a chance to enter these exclusive spaces, I discover something I never knew, and my curiosity is stimulated.”

It was this keen interest that first drew Joe to the Fukushima plant around 2005, six years before the catastrophe. He wanted to see the place that produced the energy that ran his daily life. “I requested access from TEPCO (Tokyo Electric Power Company) and photographed different types of power plants and transmission facilities, including the nuclear power plant,” he says. He still remembers the indescribable nerves he felt when he first photographed the nuclear fuel under clear blue water.

Our future is an extension of what we chose to do now.

After the disaster he appealed to TEPCO once again, pleading the necessity for the site to be recorded. Not considering himself a photojournalist, Joe had meant for TEPCO to allow “more appropriate professionals” in to document the damage; people from TV or newspapers. But after two years, still no images confirming the status of the site had been made public. SoJoe decided to take matters into his own hands and presented a plan to TEPCO to allow him in.

“Our future is an extension of what we chose to do now,” Joe says. “If we continue to make wrong decisions based on bad or insufficient information, our future may be an undesirable one. It’s my wish to use my photography to present other or alternative choices to the people, and consequently to contribute to a better future.”

When Joe first arrived to photograph the power station in 2014 it was mandatory to wear a full face mask and a Tyvek suit to protect him from radiation. “I wasn’t really afraid of risking exposure to radiation, because I was escorted by someone who had been working there since the accident and knew the site quite well,” he says.

They avoided areas where the radiation was known to be higher and used a dosimeter to measure their exposure. Rather, the awkward suit, bulky mask and three layers of gloves made it challenging to take photographs. It was also necessary for Joe’s camera to be covered with a plastic sheet to prevent contamination which made it even more difficult to look through the viewfinder. “I still remember clearly that I was more afraid that I would not be able to shoot images in such conditions.”

If I have succeeded to provoke their curiosity, then I could say that what I did was meaningful.

As for the site itself, Joe was surprised to see that most of the debris had been cleared and there wasn’t much that looked out of the ordinary. What had changed dramatically though, was a tension in the air that he had never felt before. “It was a feeling one could only experience at the accident site,” he says. “The workers there had stern looks. I hardly saw anyone smile even during lunch breaks. Back then, due to the higher radiation, workers were not allowed to stay there very long, and they had to keep the full face masks on anywhere they worked. I suppose they were frustrated as they couldn’t fully do what they were supposed to do. It was the same for me.”

Tensions started to ease in 2015 as progress was made. Today the full face masks have been retired and unless you’re going close to the reactor building, the place can feel like working at a common construction site.

This new flexibility has allowed Joe more freedom to photograph. His most recent images document robot operators in training, learning how to navigate robots that are the only chance to reach the heart of the reactor; and research fishing operations testing the radiation levels of a catch. “It is essential to intrigue the viewers if I want to tell them something,” Joe says. “If I have succeeded to provoke their curiosity, then I could say that what I did was meaningful.”

Beyond making a stimulating body of work, Joe’s primary mission is to create a lasting record of the vast decommissioning process. “Normally, I believe even documentary works need to provide some kind of entertainment to attract more viewers,” he says. “But I think an objective record would be more valuable in 30 to 40 years, than my subjective documentary. The images which are not so important in my personal opinion could be an important photographic record for the future generation. So, instead of trying to make cool-looking photos, I try to shoot a straightforward account of the current situation, as far as possible.”

When Joe gives talks about the project and shows his photographs he often hears that the plant looks different to what people have imagined; the images progress far from the picture of initial devastation in their mind. His photographs are most times their first or only look at what the site is today. “Through my photography I am hoping to motivate people to learn more – to visit the accident site or to take any spontaneous action.”