Like many of us, New Jersey artist Qualeasha Wood’s adolescence was computer-focused. She found solace in the games, platforms, and open chat rooms of the online world of the 2000s. After completing a BFA at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and an MFA at the Cranbrook academy of Fine Art, she now makes artwork specifically for Black people, including tapestries inspired by how Black women are consumed online and treated IRL. She speaks to Allyssia Alleyne about the themes in her work, and how it’s evolving.

Qualeasha Wood is no mere child of the digital age; for most of her life, the New Jersey-born textile artist has been an active and engaged citizen. Since she was gifted her first computer at the age of five, she’s constructed her own worlds in Zoo Tycoon, lorded over households of Sims, and mused about astrology, queerness, and “SpongeBob SquarePants” on her own short-lived podcast. She’s been banished from the online multiplayer game Club Penguin for profanity, courted Twitter beef by merely existing, and been doxxed on Facebook for trolling fans of conservative commentator Tomi Lahren.

Much of Wood’s visual language is rooted in the imagery of the internet. In the jacquard tapestries for which she’s best known, she collages together selfies, emojis, and other internet ephemera to explore how Black women are consumed online and treated IRL. The sturdiness of the medium balances the levity of the imagery, and enhances the weight of her themes.

Wood created her first tapestries while completing her BFA in printmaking at RISD, and continued to develop them while pursuing a master’s in photography at the Cranbrook Academy of Fine Art in Michigan. She creates each design in Photoshop and has them woven at a mill in North Carolina, though she embellishes them with beads herself.

“I’ve always loved the idea of pop-up ads and viruses and error messages in browsers. What does it mean to be warned that I’m coming? To know that I’m online, that I’m here? They feel like an invitation, but it’s a trap,” she says. “I think a lot of my pieces serve as an invitation too, but they’re also a warning to get out. I’m forcing people to be self-aware: If you do find yourself drawn to these images, and you think they’re erotic or sexy, why is that? It forces the viewer to ask a lot more questions, but that goes over some people’s heads.”

What does it mean to be warned that I’m coming? To know that I’m online, that I’m here?

Wood witnessed this first-hand last November, when her 2021 tapestry “The [Black] Madonna/Whore Complex” was unveiled as part of The Metropolitan Museum’s “Alter Egos/Projected Selves” exhibition. For two hours, she watched as visitors clamored for selfies in front of the work, seemingly indifferent to its meaning—or the fact that a woman who looked eerily like the subject was standing right next to it.

“I realized that a lot of these people don’t care about who’s in the work or what the work is doing. A lot of people are just reducing it to ‘wow, a selfie in the Met,’ and that’s inspired me to go a little further and go a little harder with my work, or in some cases, lean a little bit more into the idea of a selfie.”

But ultimately, Wood says, creating work that speaks to Black people is her priority. Growing up, she remembers feeling uncomfortable and uninspired walking the halls of the Met, where Black representation was limited on both the gallery walls and among curatorial staff, and wants to ensure others don’t have to feel the same.

“When I was in undergrad, I realized that what was important to me was filling in those gaps and creating something that a younger me would find appealing and find relatable,” she says. “How do I make art that my community can feel proud of, and want to engage with, and that people can see themselves in? How do I create something for Black femmes to relate to? How do I get it out there, and take this space, and have people believe and support this thing? That’s what I’m thinking about now.”

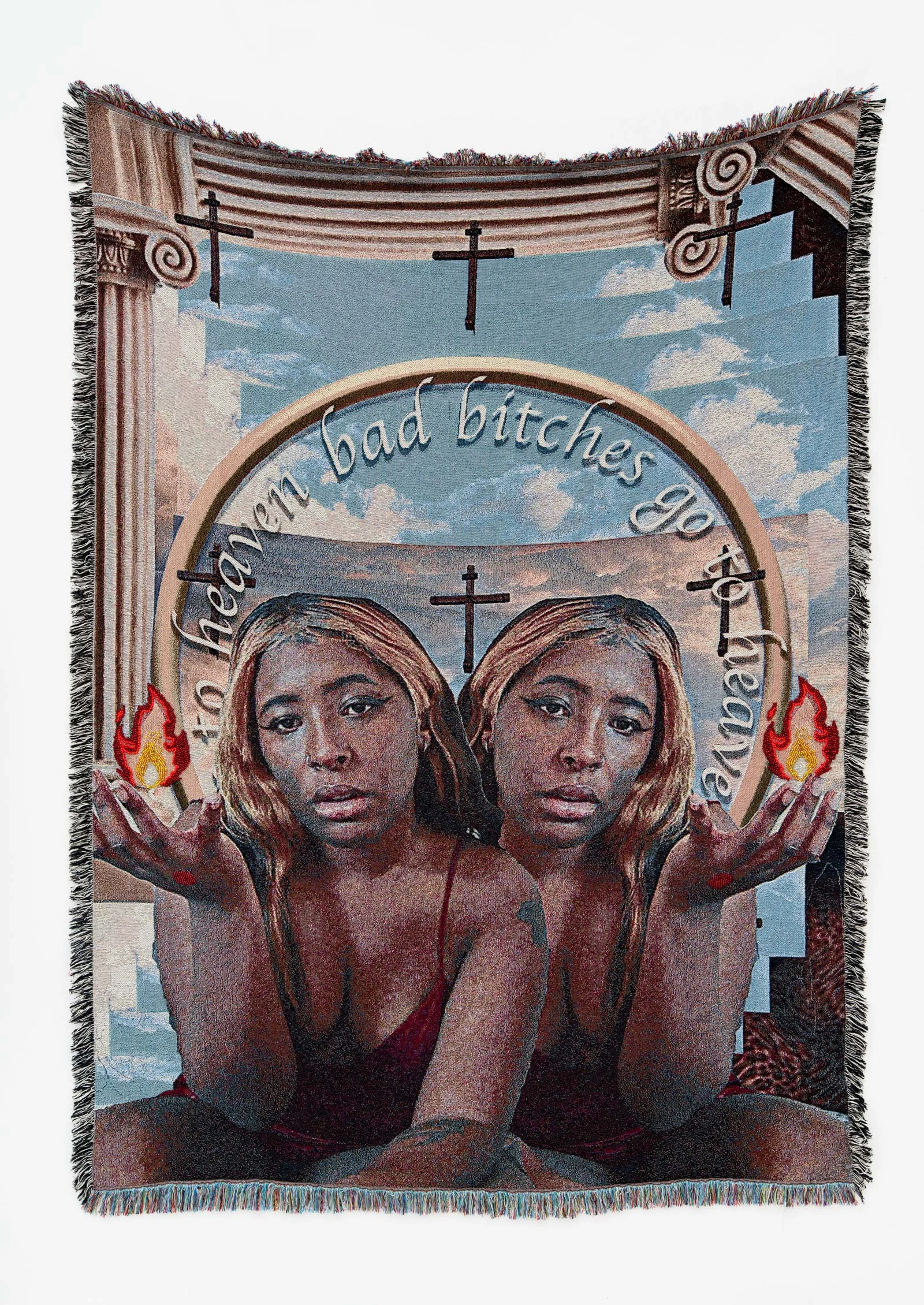

“Cult Following (2018)”

“I made ‘Cult Following’ while I was at RISD, when I felt like everyone was hanging on my every word,” Wood says. “White students would interrupt me at parties to ask, ‘Can we talk about this thing you posted on Facebook? What do you think about this issue?’ and then confess the things they’d done wrong and want to be absolved. This escalated to the point where I was telling people, ‘You need to pay for my time with this,’ and writing ‘you’re welcome’ at the end of every single caption [on social media]. As a Black queer person suffering on planet Earth, I felt that choosing to educate someone or talk to someone—or literally exist beyond leaving my house—was a gift to the rest of the world. Thinking about that further, I got to the idea of religion, and thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be wild if I transferred this work into a holy space, and became the God that these kids treat me as?”

Initially, Wood produced the composition images digitally, and as small-scale silkscreen prints. But she craved a medium that matched the weight of her subject matter. “What were the original tapestries for? They were the Bible in pictures, blown up into a huge weaving.”

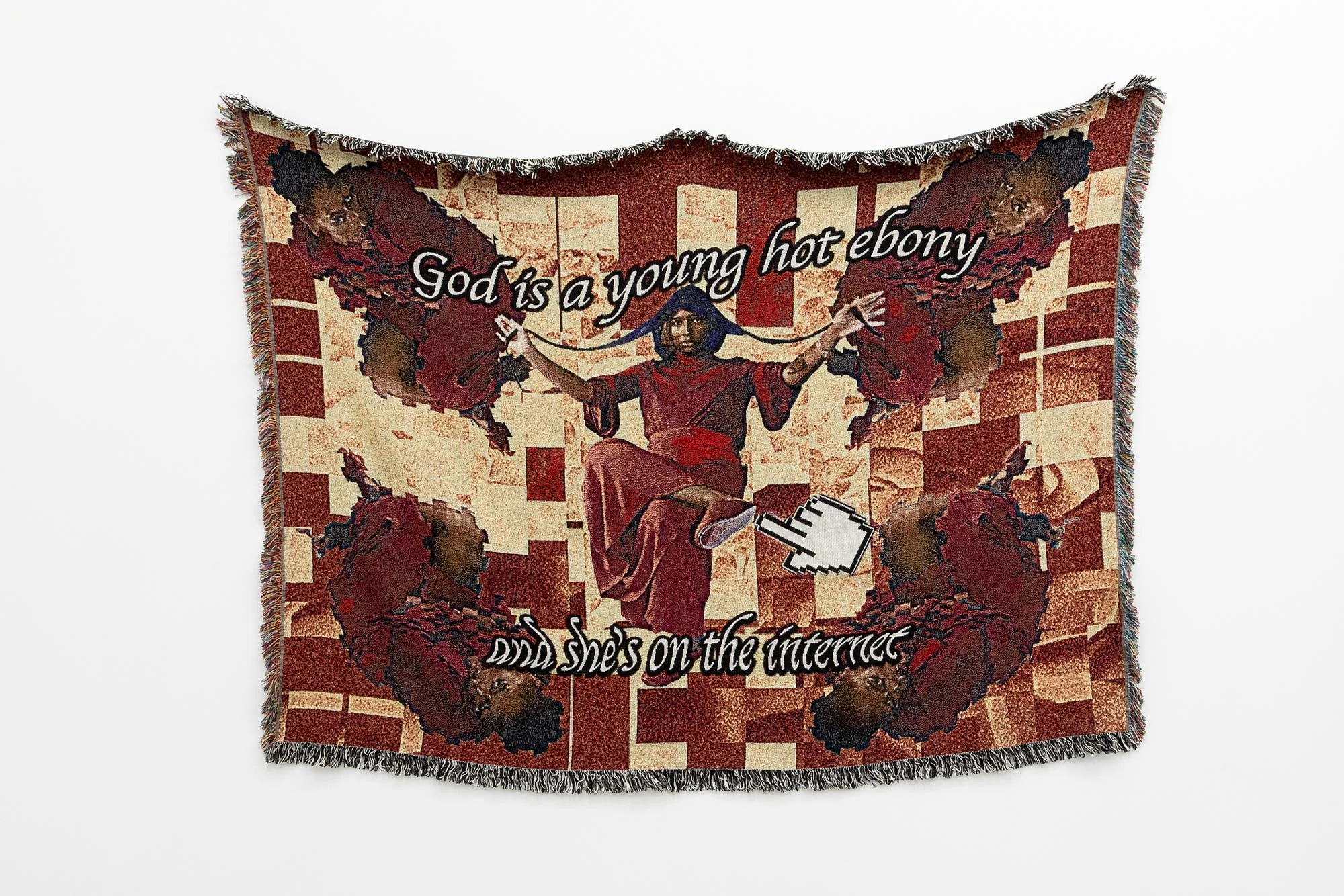

“Woke Olympics (2019)”

“Everyone is so anti-text in the art world. Text gives everything away, there’s no subtlety. But sometimes, you just say what needs to be said,” Wood explains. “At that time, I was thinking about Black death and Sandra Bland, and how all these moments of violence were being sensationalized. I was being bombarded on social media by these images and videos, and I felt like I was recognizing a cycle. Black people—and especially Black women—were dying, and then people would get on social media and act woke for a few weeks before going back to their BS. It was all for brownie points and clout and appearing to be a good person.

“The phrase ‘Black women died so you can be woke on the internet’ was out of anger, in reaction to that. But I was also asking, ‘What does the shrine look like? What does a memorial look like? What does a caption look like when you’re in these throes of desperation and sadness?’ And for me, this is all of that in one piece.”

“The [Black] Madonna/Whore Complex (2021)”

Many of Wood’s tapestries explore fetishization, voyeurism, and consumption—issues that came to a head during the final semester of her master’s at the Cranbrook Academy of Art.

“I had gotten to a point in my practice where the tapestries were loved so much by white men for reasons that I felt didn’t align with what I was doing,” she explains. “I don’t want my work, which is supposed to be about self-love and audacity, and about disrupting and taking up these spaces [within the art world], to be something that people are complicit with.”

So she stripped things back and roughed up the fantasy. She traded her turtlenecks and pantsuits for a Forever 21 slip, and embraced the rawness of the webcam and the intimacy of the desktop. “I forced myself to jump all the way out of my comfort zone and take an offensive stance with the work. I wanted to bring back this element of directly engaging with the viewer, and holding the viewer accountable.”

“fore the day you die, you gon’ touch the sky (2021)”

“With each piece, I can usually say what I had on heavy rotation while I was making it. At this point, I was listening to a lot of ‘Bound 2’ and ‘Touch the Sky’ [by Kanye West],” Wood says. “That one got me thinking about ‘The Creation of Adam’ by Michelangelo and the almost-touching hands in the literal sky, but I was also thinking about this Windows XP background. My favorite moment when I was using that program as a child was when it would freeze, and you’d be able to drag the browser across and watch it multiply. My computer was begging for help, and I was like, ‘This is so nice. I’ll just fill my whole screen.’ Now, a flat sky background is so not interesting to me. I like that digital disruption of a breaking sky.”

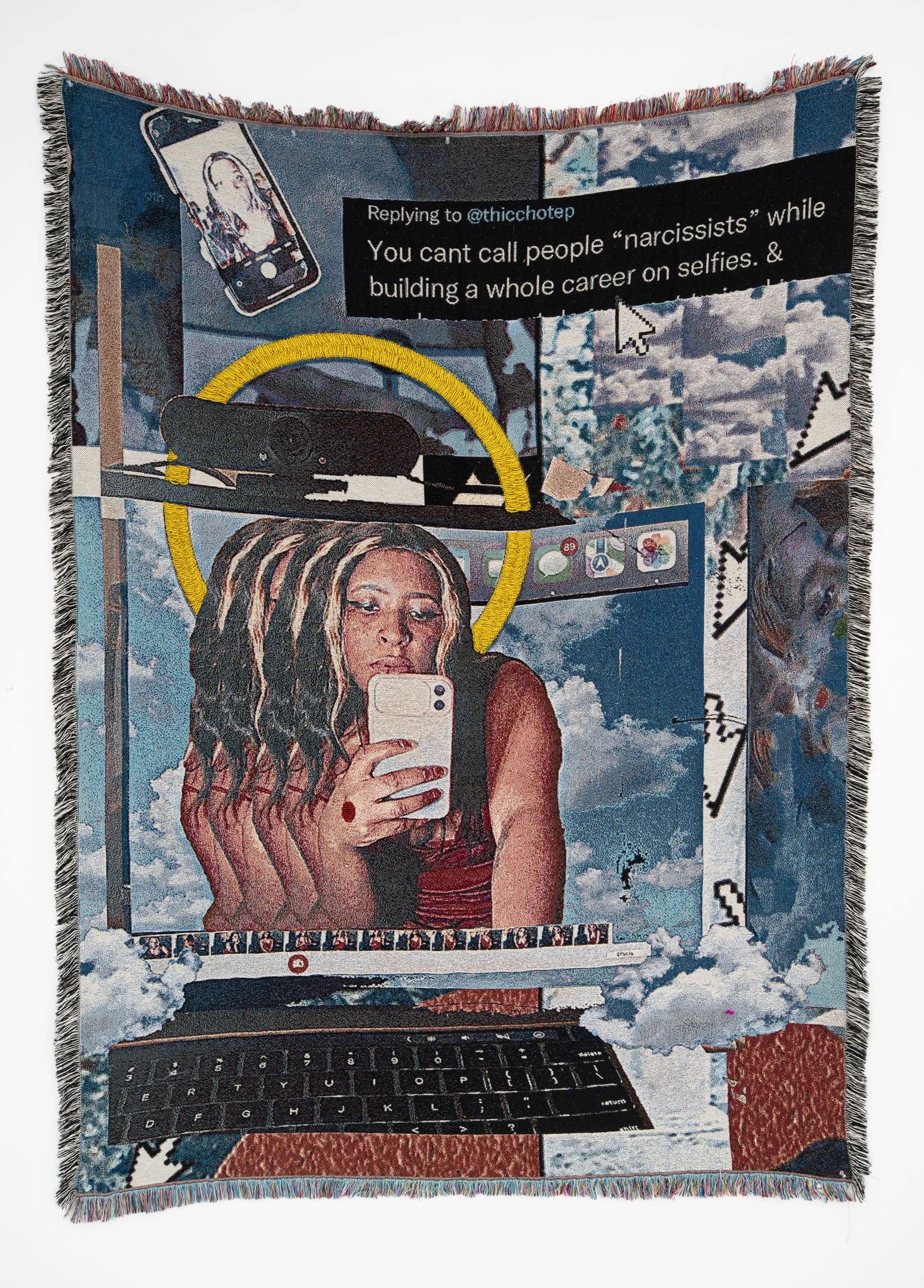

“‘FOREVA’ by Cardi B (2021)”

Once, back when she was still public on Twitter, Wood recalls getting into a heated, protracted argument with another artist on the platform. At one point, they snapped back: “You cant [sic] call people ‘narcissists’ while building a whole career on selfies.”

“That has always been a critique of my work. There are so many painters and photographers who do self-portraiture, but because I refuse to use an expensive camera or fancy paints, and arrange my images in a certain way, my work is somehow shallow and narcissistic,” she says.

Wood decided to channel the anger she felt in that moment into her work—as well as the screengrab of the offending tweet. “I figured that I could either keep having this argument my whole life, or I can put text into the art, I can put the Twitter beef into the art, and let it speak for itself. It exists, and it exists forever. In my brain, I had the last word, which is a little petty, but I think it’s important. It also feels like the equivalent of when rappers go back and forth—and the conversation about who had the best diss track. Now, we don’t even care that Drake and Meek Mill beefed. We just care that we got ‘Back To Back’ out of it.”