Creative education is vital. But creative education is, in places, broken. So WeTransfer has long been interested in supporting new types of programs.

It’s why we helped Nelly Ben Hayoun launch The University of the Underground, a free masters course that uses design thinking to challenge the way the world works.

From there, we developed the Pioneers list. Working with our pals at Creative Lives in Progress (formerly Lecture in Progress), we have identified eight schools around the world who deserve credit for doing things differently. See the whole list here.

Manga has the power to contribute to world peace. Or at least, that’s what Kyoto Seika University believes. Quoted on the course’s website, ex-president and iconic manga artist Keiko Takemiya muses on manga’s ability to become a global communication tool. “Japanese manga is spreading all around the world, and is widely accepted, regardless of national or cultural differences. Manga and animation are integrated into our daily lives, and influence our way of thinking and living.”

When Seika launched the world’s first, four-year undergraduate manga course in 2000, it immediately sought Keiko’s help. Inspired by Boys’ Love, a genre of manga popular with female readers, Keiko published shōjo manga (aimed at female teenagers) The Poem of Wind and Trees in 1976. Scrutinized for its realistic depictions of homosexuality, Keiko stood by her artistic vision.

This single-minded strength not only solidified her belief in the creation of manga as an intimately personal act, but inspired Seika’s progressive curriculum to hone individual voices – a methodology so successful that it saw Keiko rise steadily up the ranks from professor to president in 2014. Today, students benefit from one-on-one tutorials, personalized progress charts, and, like Keiko herself, are encouraged to discover their own point of view.

“Originality is very important in order to become a successful artist,” agrees professor Masahiro Ohashi, dean of the manga faculty. As a result, Seika attracts attention from around the globe, for its forward-thinking, practically led and sensitively informed curriculum. It's become the go-to establishment for those wishing to learn the skills necessary to become mangaka (manga artists).

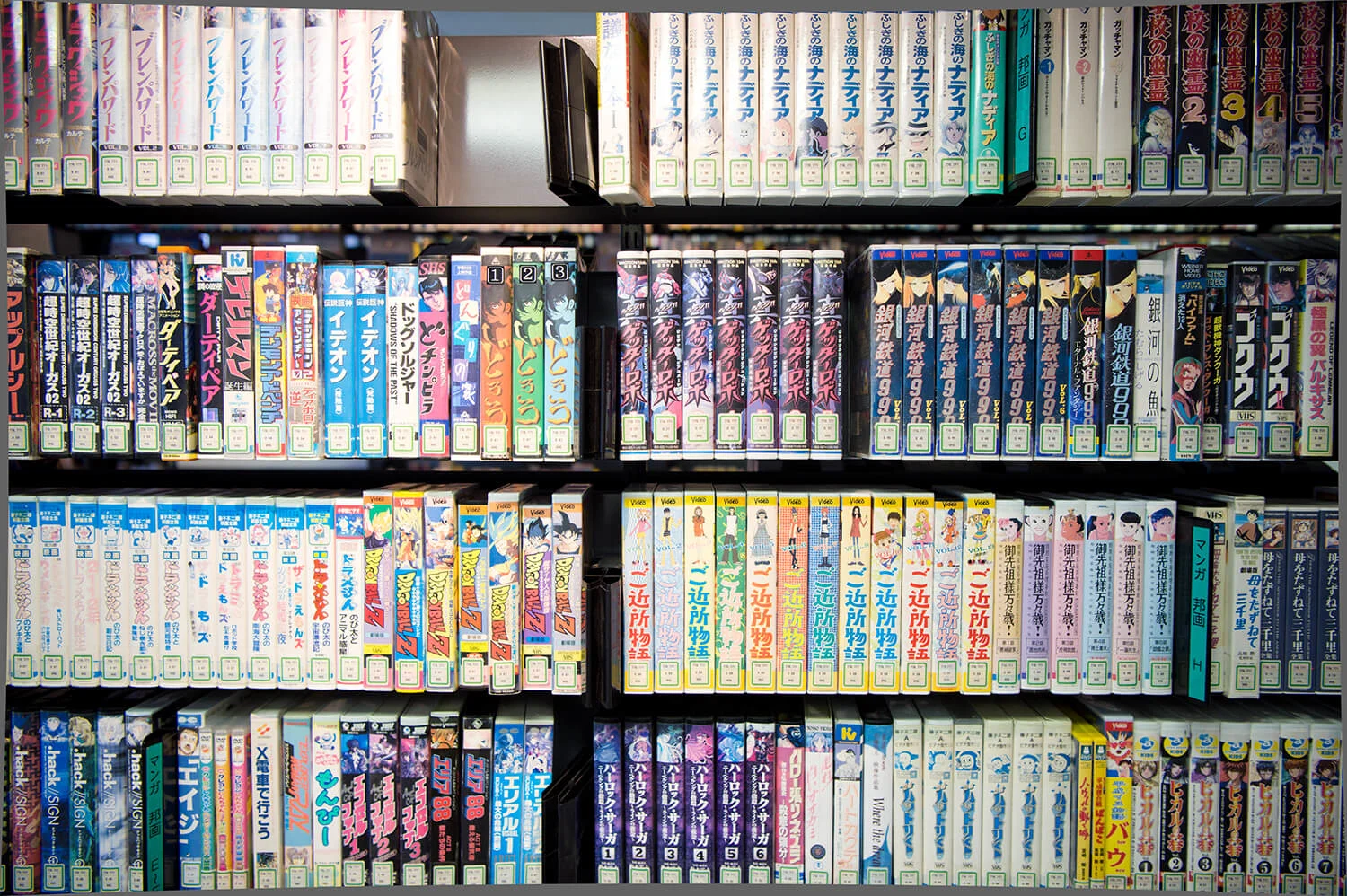

Alongside anime, over the years manga has seen its image transform from that of a niche pastime for otaku (nerds), to one of national interest and identity. “Manga and anime have a 100 to 150 year history in Japan,” Masahiro says. “They're now widely recognized as culturally representative of the country, and have been embedded in the Japanese consciousness for generations.”

Today, there’s no doubting manga’s universal appeal. Films like 1988’s Akira and the work of the iconic Studio Ghibli have gained cult followings. Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy, Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball and Masashi Kishimoto’s Naruto have all been turned into successful anime series. In 2015, French fashion designer and Louis Vuitton creative director Nicolas Ghesquière sent manga-themed models down the runway wearing Sailor Moon-styled tiaras and plugsuits reminiscent of Neon Genesis Evangelion. There are manga Shakespeare series and a manga version of the Bible. And most recently, Netflix has partnered with Viz Media to produce Seis Manos, the American manga distribution company’s own original anime series. All this merely scratches the surface of its impact.

As manga and anime spread worldwide as a cultural influence, an increasing number of people want to express themselves within these mediums.

How did a medium so intricately interwoven within Japanese culture come to be embraced globally? One of the reasons lies in how – perhaps uniquely so – manga has grown up alongside its young audience.

Manga evolves as it’s changed and adapted by its readers. Consider the culture of "scanlation," where fans scan, translate and edit manga comics into languages where a copyrighted translation is not available. Strictly speaking it’s illegal, but it goes to show the growing appetite for Japanese manga.

“As manga and anime spread worldwide as a cultural influence, an increasing number of people want to express themselves within these mediums,” says Masahiro. Today, we can add dōjinshi – the Japanese term for self-published manga – to this list.

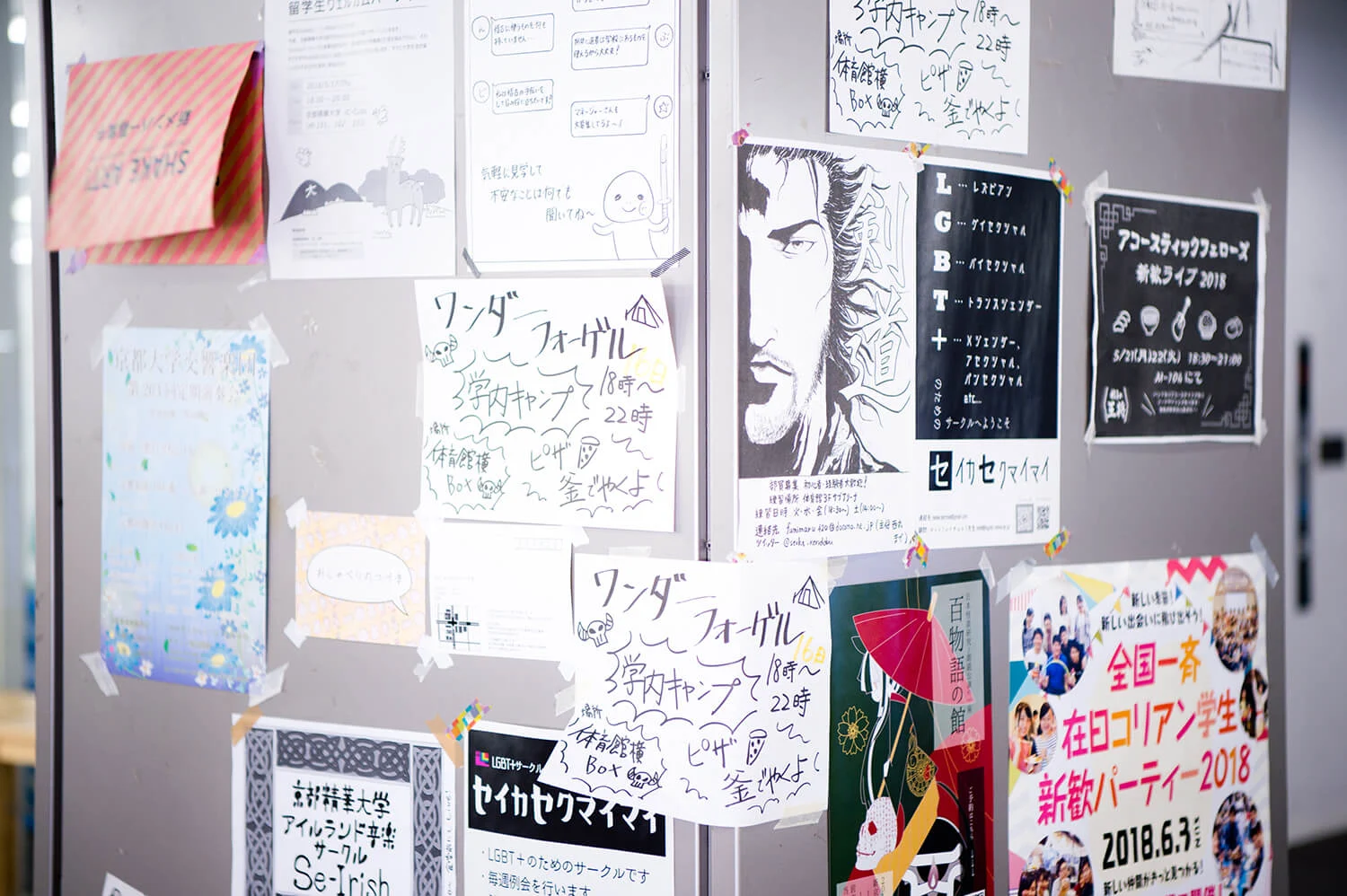

Kyoto Seika responds to the changing culture of manga and anime by embedding itself into it. Reevaluating exactly how people are coming into contact with manga, in 2017 Seika launched its New Generation Manga course, with a specific focus on web manga and self-publishing.

Scan the desks of Seika’s students, and you’ll see work tables peppered with erasers and mechanical pencils, paper and ink pens, but in recent years digital tablets have also started to appear. It claims to be the first of its kind, preparing students to work within the limitations and possibilities that digital offers.

Building on the foundations set out in other, longer-standing courses, students are taught how to create strong characters and develop and visualize compelling stories, while also covering essential skills for modern manga artists – including being a good planner, marketer and producer. This means learning about everything from choosing eye-catching thumbnails to keeping up with the market.

“We foster flexible creators who can breathe in the trend of the times,” says New Generation lecturer and manga artist Keiichi Tanaka in one of the videos on the course’s YouTube page.

The remarkable success of manga artists such as Konoike Tsuyoshi further illustrates a need to reimagine modern methods of manga production; Konoike’s comic, Kounoike Tsuyoshi to Neko no Ponta Nyaaaan! started life on Twitter before attracting the attention of a publisher. Now with two volumes and over a million sales to his name, Konoike is representative of a new era of artists who are successfully self-publishing their own manga.

In 2000, Seika made headlines for introducing the first manga course in the world. In 2018, it’s making headlines for being the first Japanese university to have an African (specifically Malian) Muslim as its president. In April this year, Dr Oussouby Sacko took up the head position, having lived in Japan for almost 30 years and initially joining the university as a lecturer in 2001.

Looking forward, Oussouby has a clear agenda, and it’s all to do with diversification. “Japanese people think they have to protect something,” he said in a recent article in The New York Times, “but someone who has a broad view from outside on your culture can maybe help you objectively improve your goals.”

Although there are no current plans to launch an English programme, and prospective applicants must be proficient in Japanese, this hasn’t deterred international students. Across the university, there are just under 400 overseas students enrolled this year from 26 countries including Brazil, Iran, China, Norway, the United Kingdom, Taiwan and Venezuela. Dr Sacko’s presidency may not be the only motivating factor here, but it’s safe to say that this his election is indicative of a new international attitude at Seika.

Theoretically and physically, Seika students find themselves at the intersection of tradition and modernity. They are based in the north of Kyoto City, and surrounded by beautiful natural forest, with central Kyoto only 20 minutes away from the site by subway, leaving them free to enjoy the city's nature alongside its urban culture.

But when thinking about Seika’s proposed vision of world peace, if manga can truly be harnessed as a global communication tool, what might this start to look like?

The methods and means of manga production and distribution may well be changing, but as manga’s influence continues to spread past Japan’s shores, Seika looks agile enough to remain at the forefront of changing behavior.

“It’s necessary to reflect on ourselves,” Dr Oussouby Sacko told Japanese newspaper The Mainichi earlier this year. “I learned about myself by observing Japanese people. Being aware of who you are is important for connecting to the world.”

Words by Marianne Hanoun

Photos by Gui Martinez

Illustration by Jordan Andrew Carter

Additional photography courtesy of Kyoto Seika University

Name: Kyoto Seika University, Faculty of Manga

Location: Iwakura, Kyoto, Japan

Current President: Dr Oussouby Sacko

Dean of Faculty: Dean of Faculty: Prof. Masahiro Ohashi

Courses Offered: Five courses offered across two departments in manga and animation. The Animation Department offers a Japanese-style Animation course; and the Manga Department offers Cartoon; Story Manga; New Generation Manga; and Character Design courses.

Number of students: 936 students (691 in the Manga Department and 245 in the Animation Department)

Fees: 1,579,000 yen (annual tuition fee)

Notable Alumni: Yoji Shinkawa, manga artist known for his work on Metal Gear and Zone of the Enders series; Falcoon (Tatsuhiko Kanaoka), manga artist known for his work on the The King of Fighters franchise; Hiroyasu Ishida known for Rain Town, Penguin Highway, and Typhoon Noruda.

Notable Faculty: Keiko Takemiya, manga artist and recent president of Kyoto Seika University; Gisaburō Sugii, anime director; Rachel Matt Thorn, cultural anthropologist and associate professor in the Department of Manga Production.