It is predicted that around 1.5 trillion images will be taken in 2021. It’s safe to assume that, out of those, only a handful are future classics. With this in mind, More Than Meets the Eye is a series by Ryan White and Douglas Greenwood that dissects the most talked-about photographs of the last decade, questioning the composition, cultural context and behind-the-scenes stories that make these images so remarkable, shareable and memorable—in short, what puts them a cut above the rest. This time, it’s a shot by Petra Collins of Rookie magazine founder Tavi Gevinson for i-D in 2014.

Context

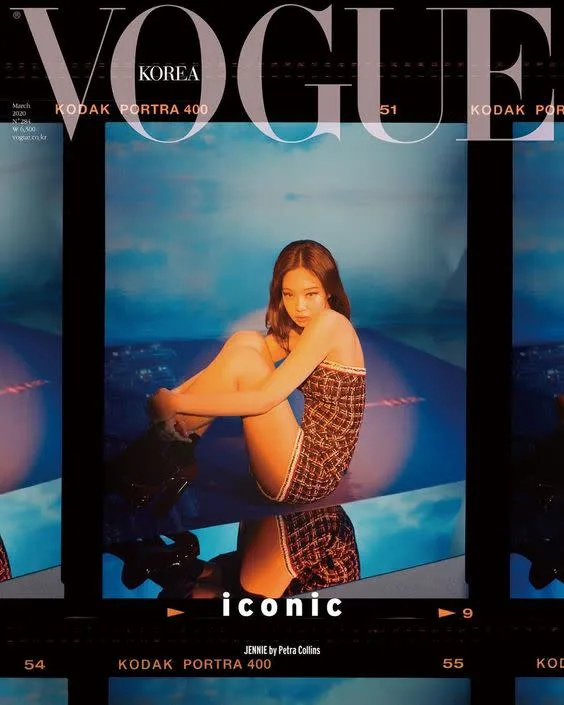

In the early 2010s, when a then-teenage Petra Collins began finding fame on Tumblr with her 35mm photography, there was no hint that an existential crisis would soon envelop the fashion industry and its top editors and photographers.

American Vogue had opened the decade with business as usual, giving 10 of its 12 covers in 2010 to photographer Mario Testino, and its remaining two, April and October, to Patrick Demarchelier and Peter Lindbergh. It wasn’t a new pattern—a decade before, Steven Meisel had shot every single cover story in 1997 and 11 out of 12 in 1996 and 1995. And, in the 1980s, Richard Avedon shot every cover – 100 consecutively – from July 1980 to October 1988.

But, by the decade's close, the landscape of fashion photography would look completely different. Little could the teenage Petra have known – scanning and uploading her images of Canadian suburbia onto Tumblr a few years earlier – she would form a vital part of this change.

Creation

There are many significant images of Petra’s to choose from, some taken at the very beginning of her career, at home in her childhood bedroom with her sister Anna, and others taken recently, for the big-budget cover stories of various international Vogues. We chose a photo from a series Petra took of Rookie magazine founder Tavi Gevinson for i-D in 2014, as it was here, around the middle of the decade, that Petra’s work first started to spill over from blogs into books, galleries and magazines.

For the shoot, Petra traveled between various monuments and landmarks of Tavi’s youth in Oak Park, Illinois, a small town outside Chicago. At just 18, Tavi was on the cusp of leaving all this behind. Although she was still living at home with her parents, she had plans to rent an apartment with Petra in New York the following autumn. For the other shots, Petra had Tavi sit awkwardly on railings in her school hallway, clutch a luminous red ball in an old-style bowling alley and – in what was becoming Petra’s signature style – sit and stare pensively, bathed in a soft neon-blue light. Here was a teenager who had accomplished incredible things at a young age but still inhabited the same spaces as her peers. But the picture that strikes most finds Tavi standing in one of her school’s bathrooms, adjusting a tiara on her head, draped in a gossamer-like floor-length white dress over her matching white crop top, skirt and Converse. In this light-blue-tiled room with little obvious charm or beauty, Petra doesn’t deify Tavi like another photographer might, or sexualize her as a male photographer often would. Instead, she creates an ethereal space in which all things about Tavi can be true at once.

Her school wasn’t even somewhere that Tavi felt fondly about. “We went around my favorite places,” she said in the i-D profile, “the roller rink, the bowling alley and my school, which isn’t really one of my favorite places, but it looks really nice on camera!” For Petra to capture Tavi as she wanted, it provided the perfect space. Asked in 2012 about High School Dream, a story she shot in her own school on her sister’s graduation day for Rookie that year, Petra replied: “I think the teenage girl is a subject I’ll be studying for a long time.”

Culture

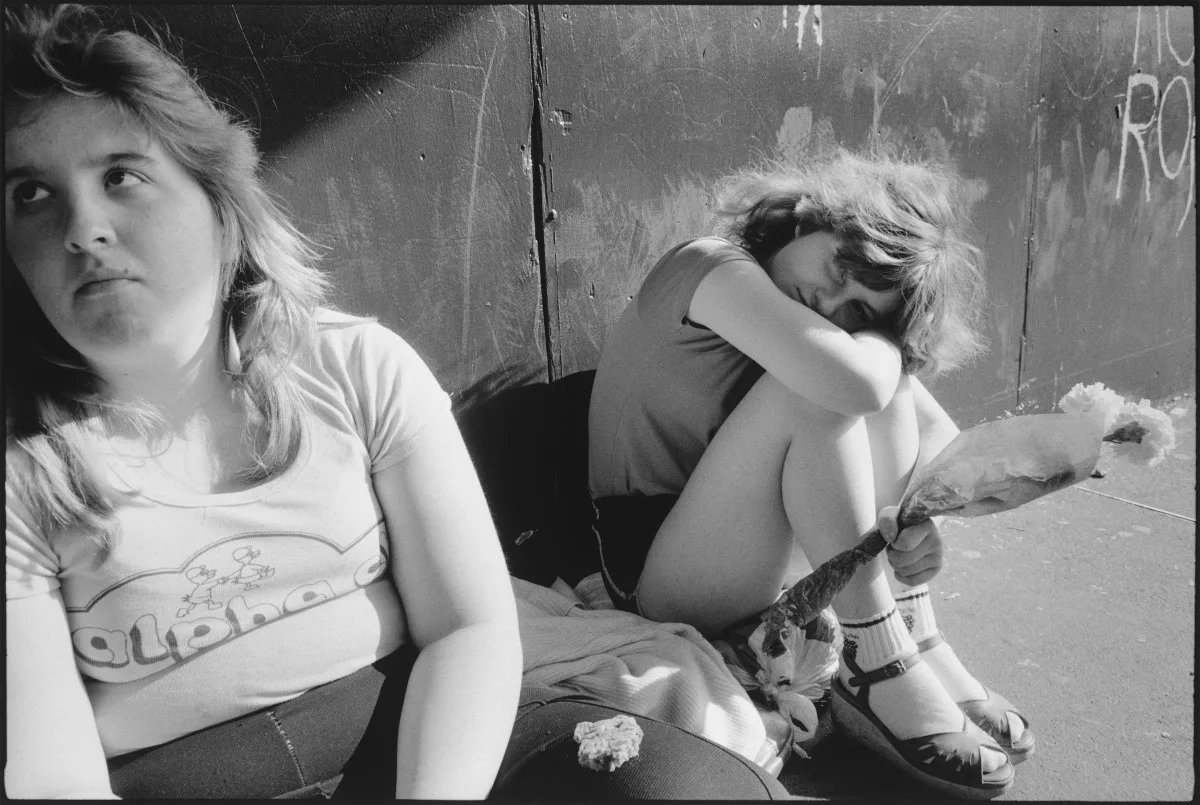

The key themes in Petra’s early work were, broadly, teenage boredom, female relationships, and a sense of unease with her own body. Of course, these weren’t radical ideas in the late 2000s. Justine Kurland approached some of these subjects with Girl Pictures in the late 1990s and early 2000s, as had Mary Ellen Mark in her candid and unsettling images of girlhood, some taken as early as the mid-1960s. In 1981, Francesca Woodman articulated a dysmorphia and alienation from her own body in Some Disordered Interior Geometries, published just a few days before her suicide at the age of 22, in a more abstract way. But Petra tapped into something more; her work seemed revolutionary, like the birth of a new movement, because the experience of her images felt bigger than the sum of their themes.

To label something millennial now conjures immediate thoughts of kitschiness—cheugy even. It doesn’t necessarily fit as a descriptor for Petra’s work. But for those born in the early 1990s, raised on disposable cameras and watching films on VHS, whose childhood turned to teenhood at the same pace as social media and smartphones were proliferating, yet who also saw seismic events like the Twin Towers falling and the Iraq War beginning on TV, her work speaks perhaps most loudly and clearly.

When photographer Sophie Mörner first saw Petra’s blog, she was instantly struck by her ability to communicate how this generation felt. “She was so fearless in the way she photographed,” Sophie says. “It was really representative for a specific generation of New York at that time. Having lived in NYC for 20 years, I love it when I can find pockets of generations and communities.” In 2014, Capricious, the publisher Sophie founded, released Petra’s first book, and accompanying exhibition, Discharge, a body of work that should be considered a milestone in contemporary photography akin to Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency and Ryan McGinley’s The Kids Are Alright. “I also love her fierce way of documenting the young girl and giving them so much power,” Sophie adds. “I loved Petra’s work from the very beginning for its intimacy with her friends.”

Composition

Growing up in the suburbs of Toronto, Petra’s strength from an early age lay in her ability to imagine a universe for herself and her friends so clearly. It was a world both magical and eerie, and one that has since been compared to Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (which, despite being set in suburban Detroit, was filmed mostly in Toronto). But it was more than just a 35mm camera and a backdrop and lighting; it was a way of seeing the world. In this image of Tavi we see her femininity first, something Petra’s photography is often concerned with, though never in a particularly straightforward manner. As we study it closer, here we find sadness too. “My work has always come out of my pain, and it’s always been a little dark,” Petra said in 2019.

There’s also a touch of horror to the image. Petra has spoken often about the inspiration she finds in classic horror films, so much so that she plans to make her own one day soon. Here, this quality feels present in small details. A high-school bathroom can often provide a backdrop to gruesome violence against teens: Scream did it, as did The Faculty. The 1981 sequel to Halloween – the mother of all teen slashers, set in a fictional town in none other than Illinois – feels particularly present. Though the film takes place in a hospital, its protagonist Laurie Strode is chased and terrorized through dimly lit hallways reminiscent of a school, wearing a white hospital gown similar to Tavi’s gauzy white dress. There’s even something in Petra’s framing of Tavi as being alone in quiet, empty suburban spaces that feels like a nod to the “final girl” trope of slasher films, or perhaps to Carrie in her tiara as she ascends to the prom podium. “My coming-of-age movies were Carrie and The Exorcist,” Petra said a couple of years back.

Perhaps these references were intentional, or perhaps they weren’t. But looking at this image with the benefit of hindsight, certainly one of its most interesting tensions lies in what cannot be seen. In 2014, the demands placed on 21-year-old Petra were growing beyond the cozy universe she’d created in her teens, and what was crucial to this transition was her ability to define her aesthetic clearly and confidently, even as the parameters for her work changed entirely.

“I had an exhibition at an artist-run space in Toronto back in 2010,” the photographer Richard Kern – who Petra assisted early on – tells us. “When I arrived to hang the show, the space was a mess but a small group of young volunteers were trying to get the place in order. I came back the next day and the place was almost ready. One young woman had apparently stayed all night working by herself because she wanted the show to be as good as it could be. I asked who she was and the guy in charge said, ‘That’s Petra, she works hard. She takes photos too.’ I asked her right there if she could help me while I was shooting, because that’s the kind of person you want to be around when you are working.” Hearing Richard’s story, it seems unlikely that anything in Petra’s works comes about unintentionally.