The Chincha islands sit 13 miles off Peru's southwestern coast and are famed for their guano, a natural fertilizer created from the accumulated droppings of tens of thousands of seabirds. In the 19th century, thousands of indigenous and Chinese laborers were worked to death to meet the demand of the Guano rush. Today, despite the value of Guarno diminishing, the islands remain guarded by the Peruvian government, warding off raiders who trade the fertilizer on the black market. Photographer Nick Ballon tells Gem Fletcher what it took to access the remote islands and the unique experience that unfolded once he stepped on shore.

On a balmy night in May, photographer Nick Ballon and writer Laurence Blair boarded the boat of retired scallop diver Rodolfo Soto in Pisco, Peru. They had to be discreet, ducking out of view for fear of being seen, as they embarked on an unusual, epic adventure under the stars.

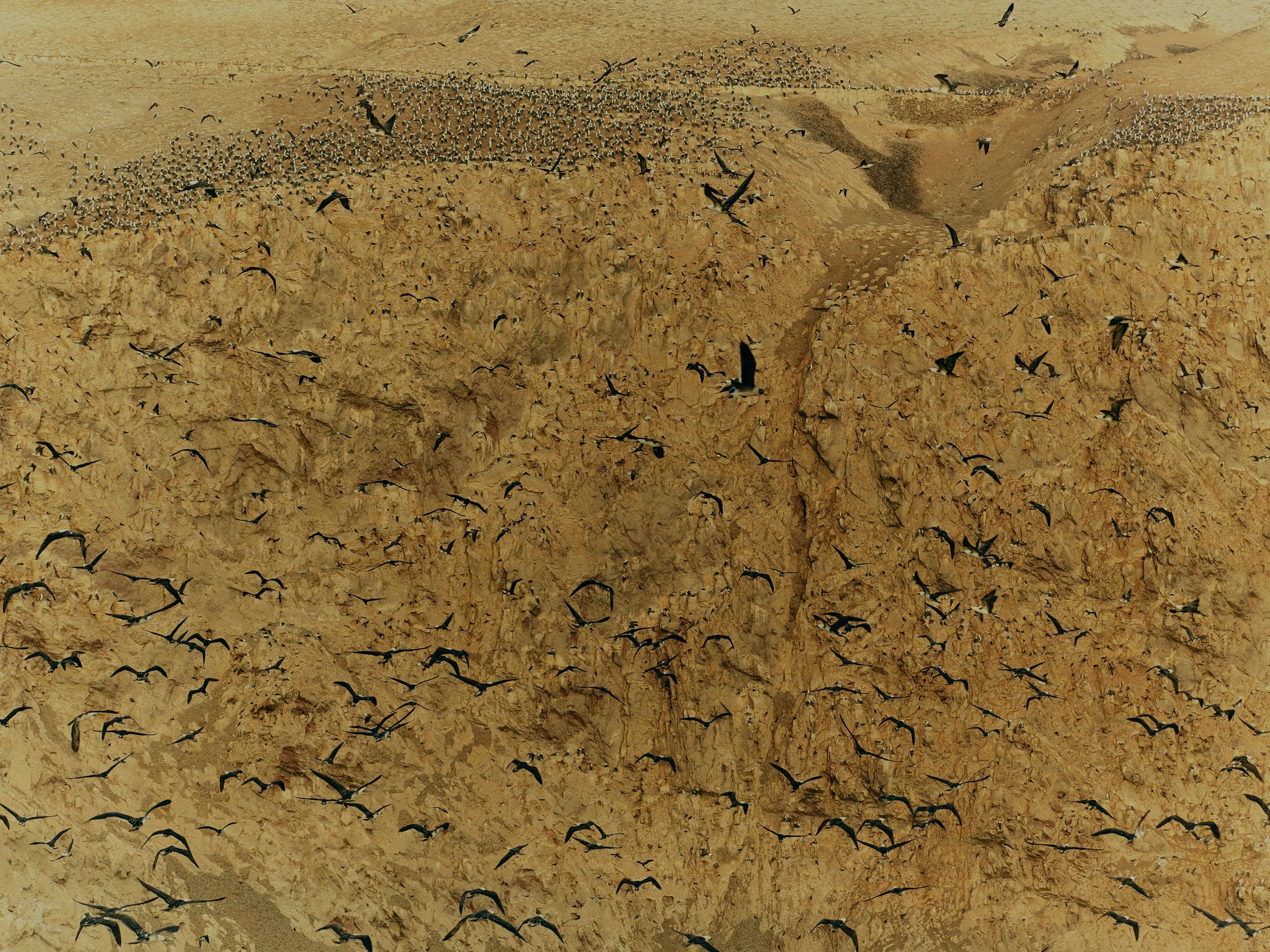

As Ballon and Blair slept, the boat quietly chugged through the Pacific to a craggy outcrop of granite islands called Chincha. “We woke two hours later to the sunrise,” recalls Ballon. “The sound of crashing waves and deafening bird squawks grew louder as we approached the islands. As we made land on what looked like a giant rock, barely a mile long and half a mile wide, our senses were completely overwhelmed. The acrid smell of ammonia from the bird droppings and dead carcasses was unbearable. It was nature in its rawest form.”

Figuring out how to make photographs under these intense sensory conditions wasn’t the only challenge for Ballon that day. His original mission, to document the Guano harvest—a renowned tradition dating back centuries in which a potassium and phosphate-rich substance born from the accumulated droppings of tens of thousands of Peruvian boobies, pelicans and neotropic cormorants is collected and used as organic fertilizer—was denied by Lima’s agricultural ministry, despite long, drawn out applications and hours of negotiation.

Much of this rejection is rooted in the dark history of Chincha's dizzying guano rush. Between 1840 and 1874, Peru exported seven million tonnes of the white gold to farmers in Britain and the USA, fuelling their industrial and agricultural revolutions. The magical agricultural properties of guano, referred to as gold for well over a millennium, sparked one of history’s more curious resource conflicts. At the same time, thousands of indigenous and Chinese laborers were shipped to the island, forced to live in dire conditions and often cruelly worked to death to harvest the prodigious natural fertilizer.

The oldest guardaisla in service writes poetry to pass the time away from his family, but he’s dreading the thought of retirement and the noise of the mainland.

In response, Ballon pivoted his attention to the three guards, Mauro Tomairo, Augusto Martinez and Jhon Fernandez. Known as guardaisla, the men live in pairs, and sometimes alone on their own island, fishing for their food, counting the birds and engaging in creative work to stave off melancholy. “Jhon—the youngest guardian—told us excitedly about creating gardens, greenhouses and scientific experiments,” explains Ballon. “He wants to market the food waste of the harvesters as another artisanal guano supply.”

In truth, life as a guardaisla can sometimes feel like a curious modern experiment in solitude. Augusto counters the isolation by bonding with the seabirds, entranced by their anchovy-bearing courtship rituals. Some of these modern-day hermits have become institutionalized: “67-year-old Mauro Tomairo is the oldest guardaisla in service and writes poetry to pass the time away from his family,” says Ballon. “But he is equally dreading the thought of retirement and the noise of the mainland after 40 years on the islands,” even telling Ballon he felt the birds show more affection to each other than humans.

The Peruvian government employs guardaisla with the dual task of warding off marauders who visit the island to poach birds or steal guano, and facilitating the annual harvest, in which three hundred people visit to painstakingly extract guano by hand before it is distributed to Andean farmers. As Ballon’s collaborator Blair points out, the peak of the Guano rush might be over, but a subsidized 50 kilogram sack is worth 50 soles (around 13 US dollars), earning double that on the black market. “That’s a lot of cash in a country where a quarter of people live in poverty,” Blair says.

Ballon’s experience on Chincha was more akin to an endurance test. From dawn until dusk, he trekked two of the three islands with the guardaisla’s, climbing their highest peak and tracing the disused piers, warehouses and train tracks as well as observing the vast wildlife. Conditions were tough. Birds were dive-bombing constantly around their heads, and negotiating the response he was having to the smell and sounds, while carrying heavy equipment and working under strict time pressure, required profound perseverance.

Our senses were completely overwhelmed. It was nature in its rawest form.

Contrary to Ballon’s challenges on the island, his photographs appear calm and peaceful. Rich hues bring mystery to the natural flow of rolling hills and craggy rocks, punctuated on occasion by the severe lines of man-made structures. Flocking birds patina the skies while the raw textures of nature are subtly softened by the creamy matte drape of the guano that covers everything in sight. Like much of the Peruvian coastline, the Chincha islands are often draped in a thick band of foreboding clouds which, while challenging to work with for an image maker, gave Ballon’s work a dramatic cinematic quality that somehow conjures the haunted psyche of the island’s past.

This work is personal for Ballon, who uses his photographic practice to understand his Anglo-Bolivian heritage. “Growing up, my father didn’t tell me much about South America. It wasn’t until he moved back to Bolivia later in life that we began to discuss the intimate details of the region’s history and politics, igniting my passion to uncover more through my work.” Ballon’s early projects became a collaborative bonding experience with his father, as they charmed and cajoled their way into stories and spaces. When Ballon lost his father in 2013, he knew it was now on him to pick up the threads of his heritage and continue to reconnect with his roots.

As a storyteller, he doesn’t shy away from hard things. “I put myself in these challenging situations quite a lot,” admits Ballon about his creative process. “There has to be pain in making pictures.” Over the last decade, he has lived at debilitating high altitudes with potato farmers up in the Andes, fought hard for access to Bolivia’s Navy and trekked Peru's Sacred Valley to photograph herding families. “Performing under these pressures makes picture making exciting,” he says, laughing. “There’s something inside of me that desperately wants to photograph things which haven’t been seen. It sometimes takes months, or even years, to gain permission to make this work. But when you finally reach your destination and can make work, that’s when I feel the most alive.”