Family photo albums hold a unique form of nostalgic pleasure. Despite their careful construction—centering happiness and erasing imperfection—they are a visual reminder of our profound familial connection. For Maria Mavropoulou, growing up without a family archive interrupted her sense of belonging, leaving her with the haunting sensation that something was always missing. Rather than accept this lack, she turned to AI to fill in the gaps. She tells writer Gem Fletcher about the catharsis born from reimagining her past and what this new breed of machine-led images reveals about who we are and how we see the world.

Maria Mavropoulou doesn’t have many family photo albums. She doesn’t have images of herself as a baby or know what her mother's pinscher Malishka looked like or what it felt like to occupy the home in Tashkent, where she grew up. For three generations, her family changed residency multiple times before she was born, moving between Uzbekistan, Russia and Greece—sometimes at will, sometimes forcibly—losing many belongings along the way.

Until recently, Mavropoulou’s only connection to her family history was a handful of photographs and anecdotal stories. “The family album is a construct of memories; a visual proof that things happened in a certain way, and for me, so much was missing,” explains Mavropoulou. “While this is my story, and I have accepted it, I still yearn for a visual history.”

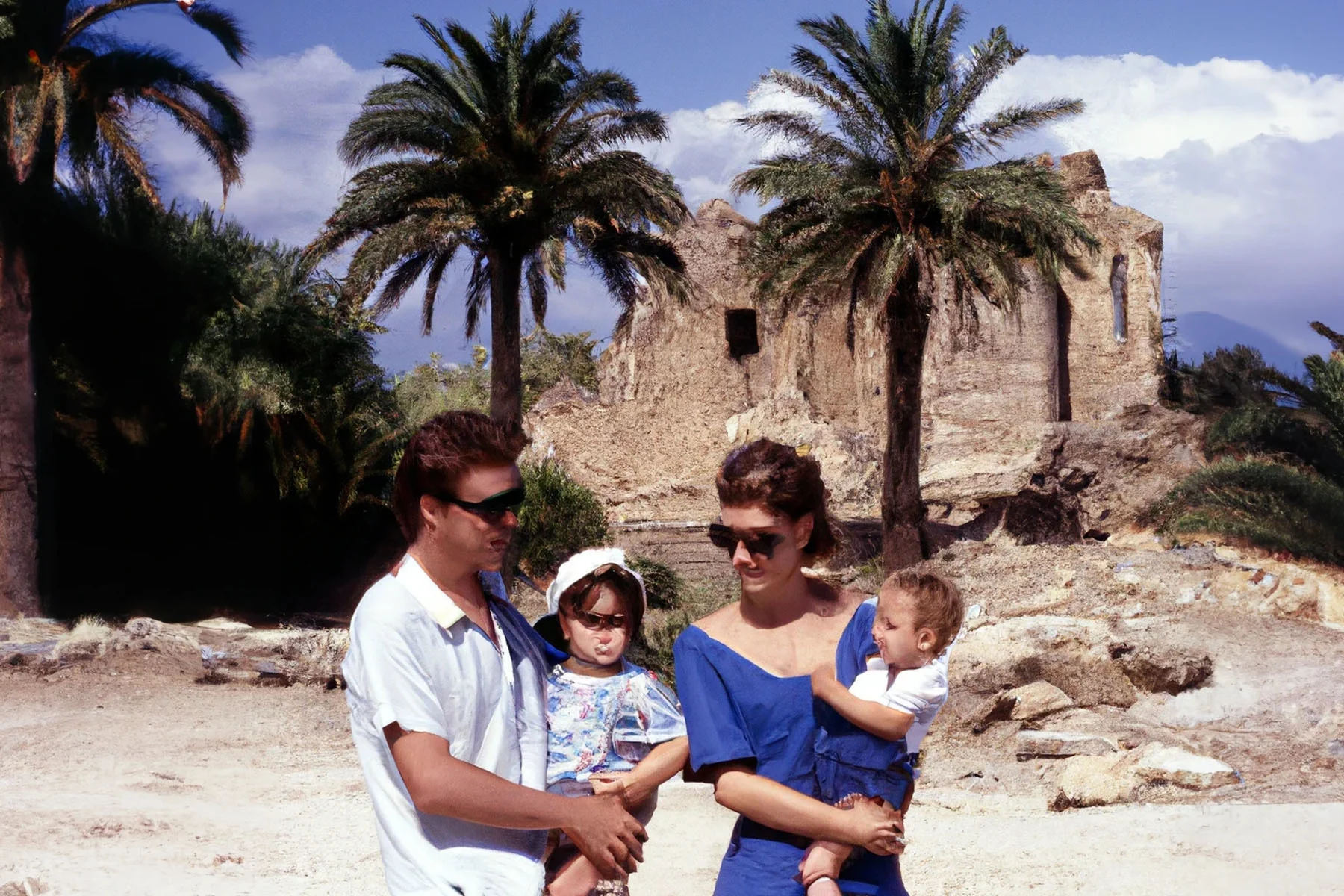

In 2021, she began using the family information she did have as prompts for DALL-E, the text-to-image program that blends artificial intelligence and deep learning methodologies to generate digital images. The resulting project, “Imagined Images,” includes over 400 frames describing seven decades of family history depicting weddings, births, holidays and birthday parties alongside mundane everyday moments.

The images embody all the hallmarks of amateur family photography; imperfect framing, awkward posing and forced smiles. Anchoring us to each decade via subtle cues—fashion, design, beauty, behavior and photographic approach—born from DALL-E’s ability to synthesize typologies of any given scenario in a particular time and place from the millions of data points it draws from.

Early in the project, Mavropoulou would verify the images DALL-E created with her mother, and much to their surprise, there was a disarming level of accuracy. “It was not only emotional but informative,” she says about the creative process. “The AI seemed to know more than I did about a specific place and time, adding details to images I wasn’t aware of, like my mother's work uniform and design elements of our home and garden. While the images don't have any fundamental tie to reality, there is some version of knowledge in them due to the program’s ability to draw from such vast data sets. We attribute fakeness to AI images, but in many ways, they reflect a universal truth.”

Visual mutations drive much of the irreverent appeal of post-photography, creating aesthetic novelties within our visual language. While the scenarios in “Imagined Images” have a level of accuracy, the rendering of human faces leaves them unrecognizable, creating uncanny and sometimes nightmarish distortions due to the infancy of the software. This design glitch is important to the artist, who wants the viewer to see that they are looking at a family, rather than her family.

This is all part of Mavropoulou's mission to subvert new technologies like VR, GAN, and AI to interrogate, rather than celebrate, the relationship between humans and machines, dissecting everything from algorithmic bias and representation to the power politics in our online world.

It wasn't enough for Mavropoulou to fill in the gaps in her family album; she also wanted to imagine moments that never happened, playing with the notion of “what if things had been different.”

“I reflect a lot on my family’s history, and what if my family had made different decisions? Or we moved in another direction. Maybe we wouldn't have lost everything,” she says. She went on to visualize moments she imagined—memories that went unphotographed, moments she wished had happened, but didn’t. “I don’t have a single photo of a birthday party because I never had one, so I added many images of parties to help me reconcile my actual story.”

On a personal level, Mavropoulou describes the project as “healing”—rewriting the past in order to shape her future. Conceptually, post-photography reckons with more philosophical ideas about the notions of truth and fakeness, as well as the uncomfortable question of whether it even matters. Is an image less meaningful if it’s illustrative rather than authentic? What does it mean if AI images provoke feelings in us the same way genuine photographs do?

Mavropoulou’s enigmatic project opens a conversation about all these questions and more, transforming the instant prompt-result paradigm into a form of cultural archaeology, offering glimpses into the human condition. “What excites me is using technology as a mirror,” she says. “I’m turning a spotlight on technology, trying to understand how it sees us and, in turn, how it shapes how we think about ourselves.”