Since Nigerian artist Marcellina Akpojotor first began creating her acrylic paint and textile works, women have been her focus. What started with her depicting the faces of the inspirational women around her has now evolved into a full study of womanhood and family on the African continent, and the specific fabrics she uses in the process add another layer to that study. She tells Vincent Desmond why using the Ankara fabrics worn by generations of women there help her to capture their shared history, and to paint a picture of the way things are changing for women over time.

As a child, Marcellina Akpojotor spent a lot of time with her father, who worked as a sign maker. She would spend hours watching him work with different materials, and she soon became part of the process, helping him and learning from him. Today, she cites that experience as the genesis of her interest in art and as her first apprenticeship.

“I remember going out early with my father every morning,” she says. “My school was far from where we lived but it was close to where he worked, so we’d leave the house together and when I finished school I would meet him at his shop and watch him work.” Helping him use different unconventional materials to make the signs played a significant role for Marcellina, as it encouraged her to see the artistic potential in everyday materials, and that eye has made her one of West Africa's most distinct artists.

I see fabric as a way to commemorate the experiences of this huge community of women.

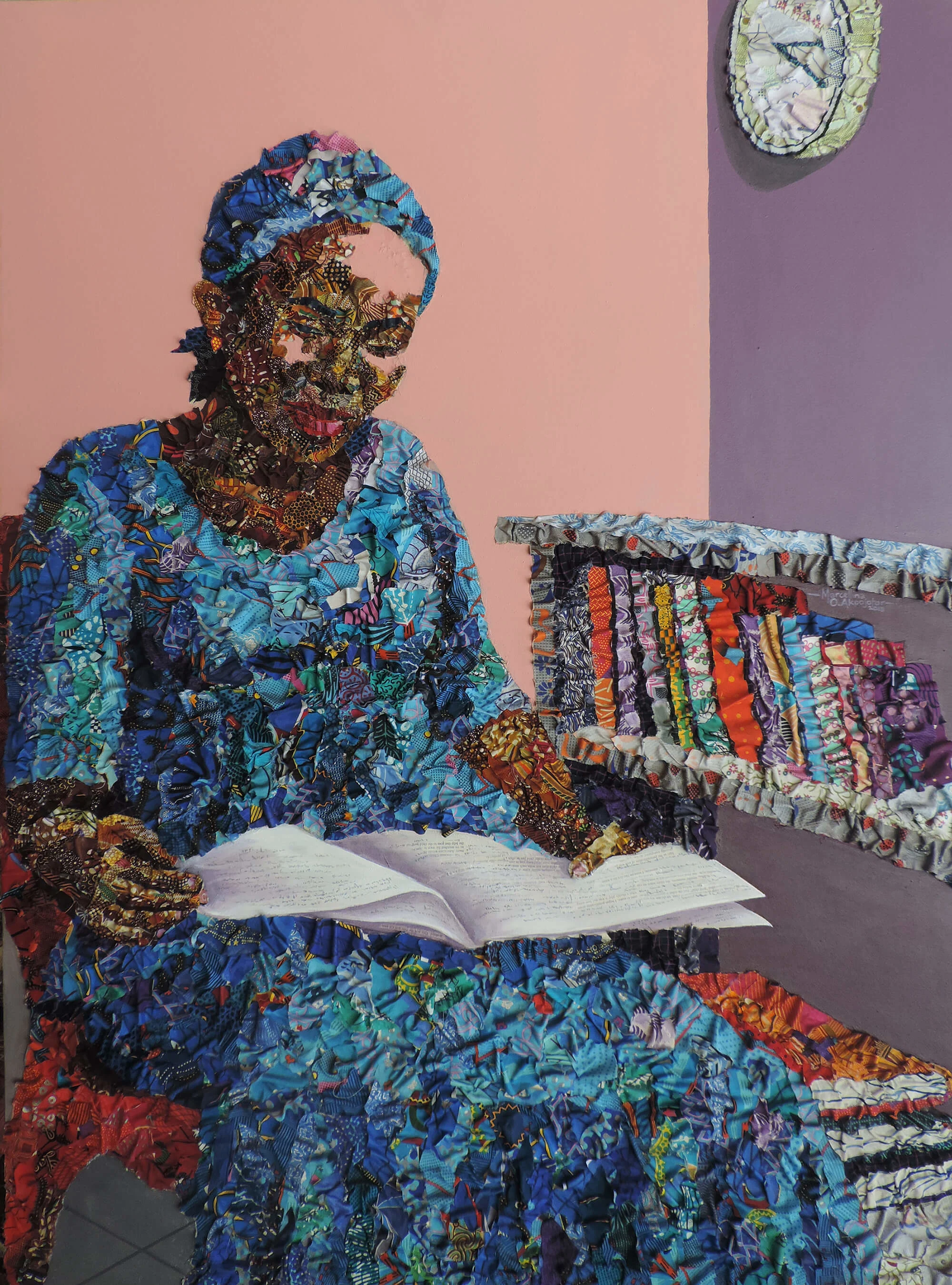

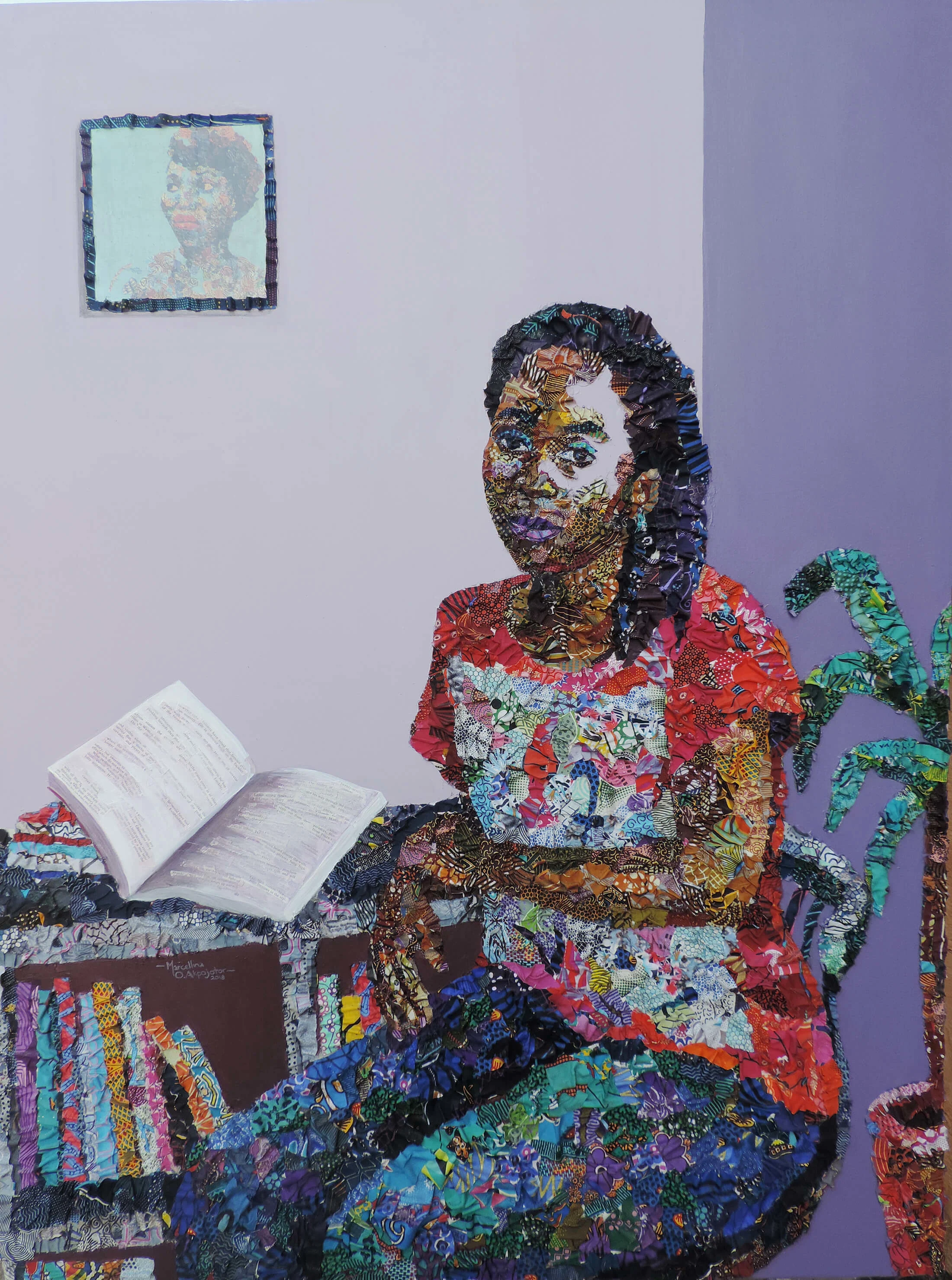

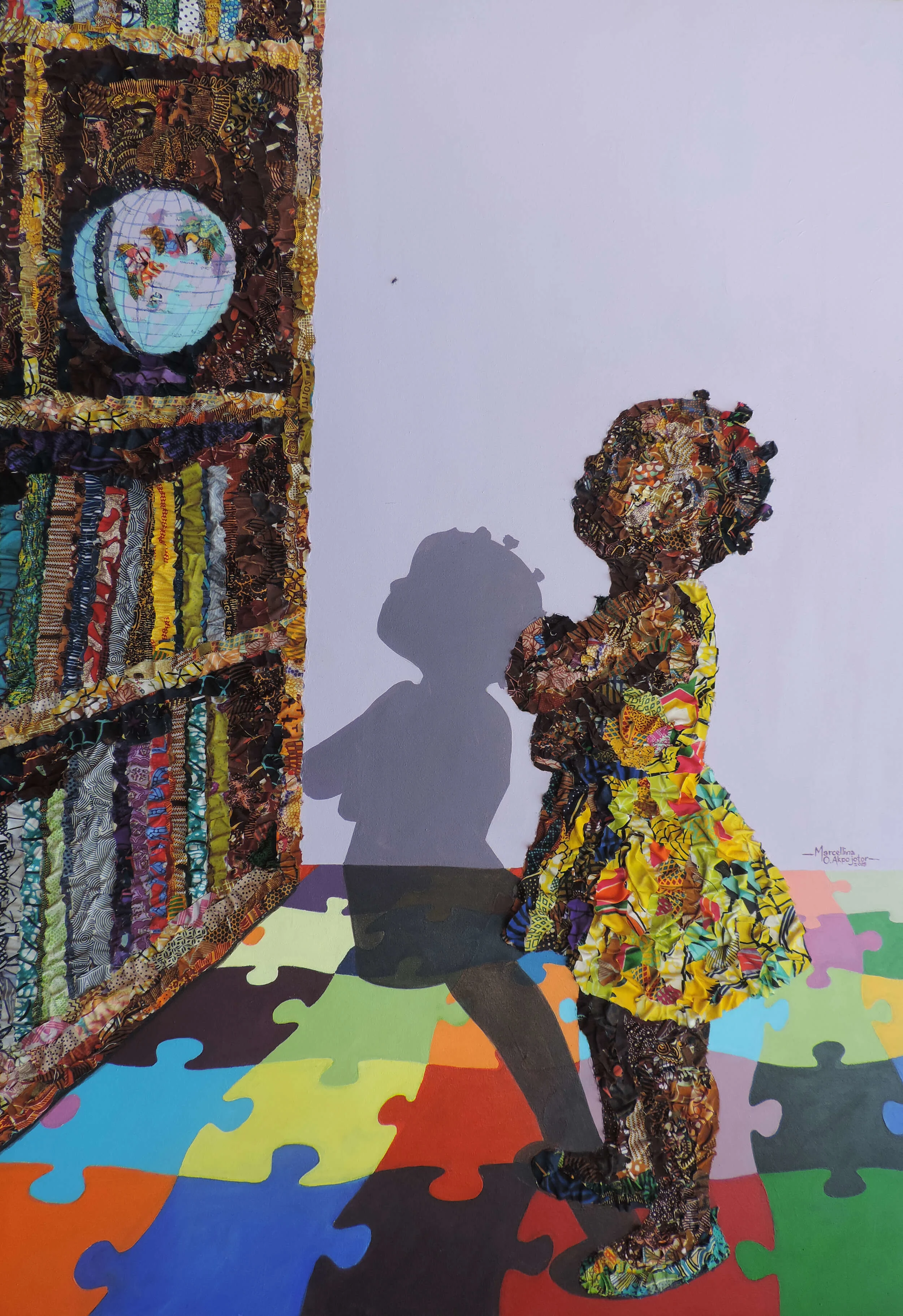

“When I first started, I would use fabrics to recreate the faces of the women around me. Back then, it was a way to encourage them and appreciate them and show them in the right light,” Marcellina explains. “When I questioned why I was so fascinated by women and women's rights, I remembered that when I was younger my mum would tell me of her great grandmother who used to say that if she ever returned to this world, one of the first things she would ask for is an education, a book and a pen. I thought that was very powerful.” In her 2018 series “Daughters of Esan,” Marcellina used fabric to illustrate five generations of women; beginning with her great-grandmother, her grandmother, her mother, herself and then her daughter, all shown reading or beside a bookshelf to subtly explore the quest for education and the way things have changed over time.

“I was looking for images of my great-grandmother, but I couldn't find any, and she passed on when I was two years old, so I don't have any memories of her. As a figurative artist, I didn't really have any references, so I decided to find other ways to represent her by taking motifs from her life and using them to represent her and bring her essence into the work,” Marcellina says. “For example, Esan, where she lived, has red soil, so I brought that into the work. I was using everything I knew of her as a lens to look at the past and how all of it could have shaped her as a woman.”

I want women to see within my works that they are deserving of respect and that they are powerful.

Marcellina primarily uses discarded pieces of Ankara fabric that she sources from local fashion houses herself. She finds these fabrics offer her a way to connect to her community and their shared history, two topics that are integral to her work and practice. “Fabrics are often embedded with their own stories,” she says. “Stories that I'm not even aware of. Nonetheless, those stories – of little joys, happy celebrations, and even mourning – are all very important to the end product.” Because of the memories Marcellina believes these fabrics tend to carry, she has to have conversations with them, from the beginning of the process as she sources them until the end when she finishes, ensuring she understands them and uses them in the way they want to be used.

“I pick them up from the floor and start a conversation with them,” she shares. “I have a story I want to tell, and I also know the fabric has its own stories, and I want to maintain both of those, so they can add to one another rather than change each other’s. It's important to me that I don't alter the colors of the fabric. The acrylic paint is what allows me to get my own colors down onto the canvas, and to play with the intensity of the piece, and then I use the fabrics in their most authentic form.”

Marcellina finds that fabric, especially from Ankara, works the best for her art and attempts to honor memories, history and community, because they’re cultural signifiers that have been worn by generations of women before her, and are still worn by the younger generations following her. “These fabrics remind me of community, of people coming together, which is important because my work is very interested in communities and the continuous dialogue that happens within them,” Marcellina says. “My work makes me look at fabric as a way to design and make motifs to commemorate this huge community of women and their experiences, and using fabric they would have or could have worn, it might carry with it what they might have felt. I can try to capture their essence and share that with a new audience.”

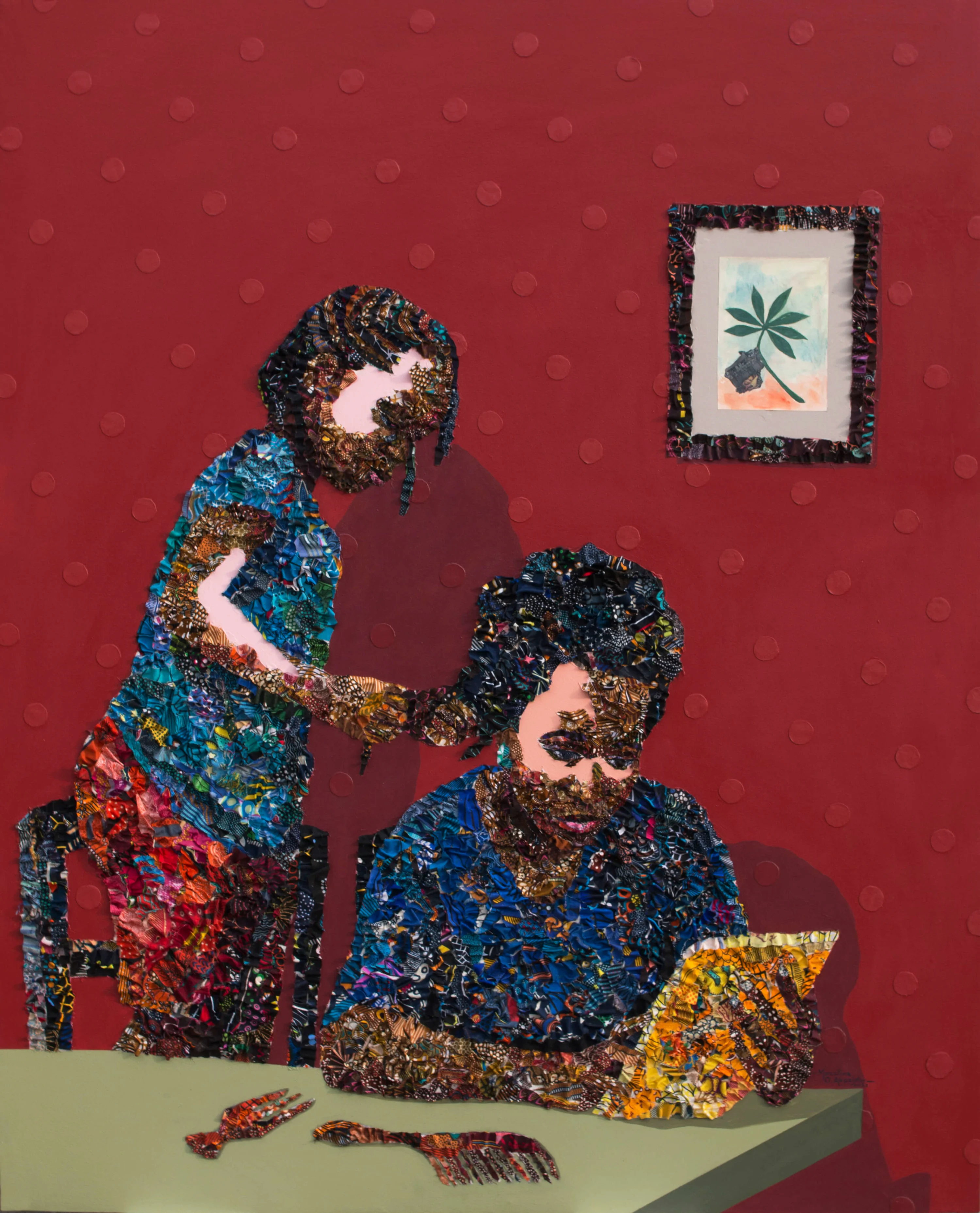

The result is emotionally arresting work that explores community, femininity, and womanhood in a very African context, and often weaves stories that touch on all these topics at once. All of Marcellina's work is connected and continuous and is adding to an ongoing dialogue about being an African woman. Her multi-generational portrait “Songs from Home,” for example, showed herself and her first daughter at the feet of her mother and grandmother, featuring a portrait of her great-grandmother on a shelf in the corner, cassava leaves dotted around her to represent her occupation as a farmer. Much like her previous projects, it interrogates feminism in contemporary Africa with family and community seated at the centre.

By so often showing multiple generations of women in the same place, Marcellina is creating a bridge between them, bringing them together – no matter the environment they had to live in – in her creative world, where smiles abound and books and education are never far away. When she creates, it’s with a clear plan. She wants to tell stories that leave women feeling respected and seen and bring up the conversation around women in Africa using everyday familial scenes, so that those who come across her work can identify with the stories in the paintings. “When women look at my work, I want [them] to feel respected, to feel important,” she says. “I want women to see within my works that they are deserving of respect and that they are powerful.”