In much of India, upholding heteronormativity and the gender binary is entrenched in every aspect of society, from visual culture to education. From a young age, Keerthana Kunnath knew that questioning this would have consequences—but refused to compartmentalize her life and aspirations for the comfort of others. Here, she tells Gem Fletcher how photography can challenge these systems and make space for new possibilities.

“I think my work is about building a world where I can belong,” says Keerthana Kunnath. For the last three years, the Indian-born, London-based photographer has focused her practice on exploring same-sex relationships and gender-expansive people in the South Asian diaspora. The work is a direct response to her experience growing up in India as a Queer woman—navigating societal pressure and exclusion—while desperately trying to live her truth. Through collaborative portraiture, she asserts the value and virtue of these hyper-politicized, marginalized identities, ensuring they take up space both pictorially and culturally.

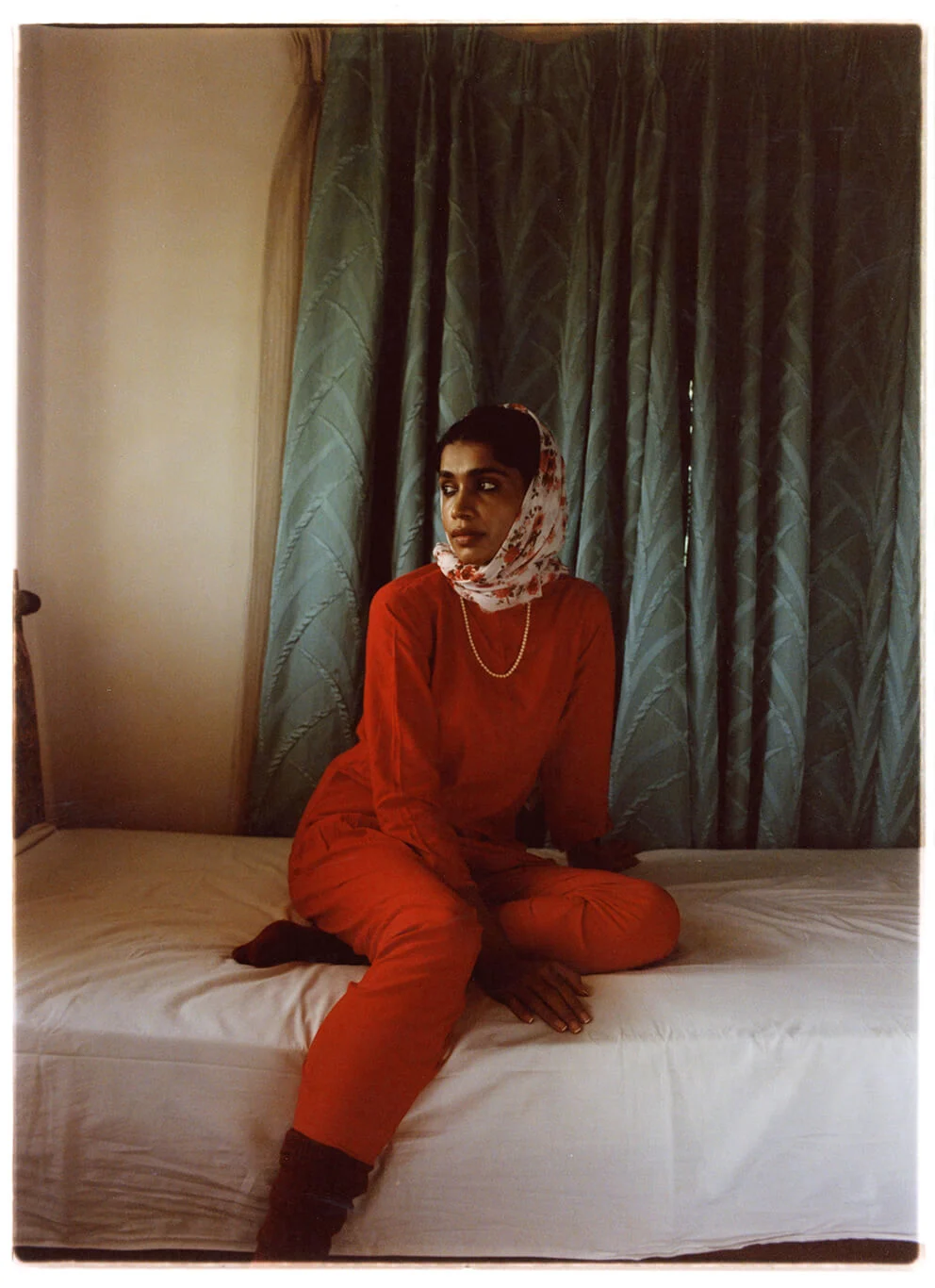

It’s in this sentiment that “Aval” (her) was born. The series subverts the visual tropes of Bollywood by appropriating its familiar poses and scenarios and reimagining them with same-sex couples. Shot in London and cast through Instagram, the tender and intimate images offer her collaborators a path to escape invisibility and validate their sexuality. The series embodies freedom, elegance, desire and self-assertion, capturing a sense of aliveness free from the weight of contextual politics.

Making “Aval” was also healing for Kunnath, who struggled to understand her own queerness growing up in Beypore, a small conservative town in southern India. “I was completely confused,” she shares. “The society is extremely conservative, and heteronormativity is the default. I didnt understand what I was feeling and if it was normal. I had no cultural references for the LGBTQIA+ community. No one talks about it.” While legal rights in India have evolved in recent years, queer people do not occupy the dominant culture. Their lives are often dismissed as fictional, forcing them to stay closeted in order to assimilate or live their lives in the shadows.

For Kunnath, “Aval” is about representational justice while also finding a way to critically engage with how heteronormativity is embedded into the fabric of South Asian society - a result of social conditioning predominantly shaped by advertising and mainstream cinema.

“Bollywood illustrates the epitome of life for many in the Indian society,” Kunnath explains. “It's highly dramatic and hyper-sexualized visions of life, gatekept by male creatives. In these movies, violence against women is romanticized [e.g. women being stalked or disrespected for the entertainment of the male audience.] Cinema tends to perpetuate ‘damsel in distress’ narratives that always give more power to men. If a female character is ambitious, consequences occur as a gentle reminder of society's limitations on anyone but men.”

It wasn’t until Kunnath left her hometown of Beypore to study, first in New Dehli and later in London, that she could begin to confront her culture. Photography became a tool in renegotiating her relationship with India and understanding how it shaped her psyche, while creating the visual world she so desperately craved as a young person. Through image-making, Kunnath seeks not just to emancipate herself through corrective gestures, but to cultivate new modes of creativity and community that deepen consciousness and lay a blueprint for future generations.

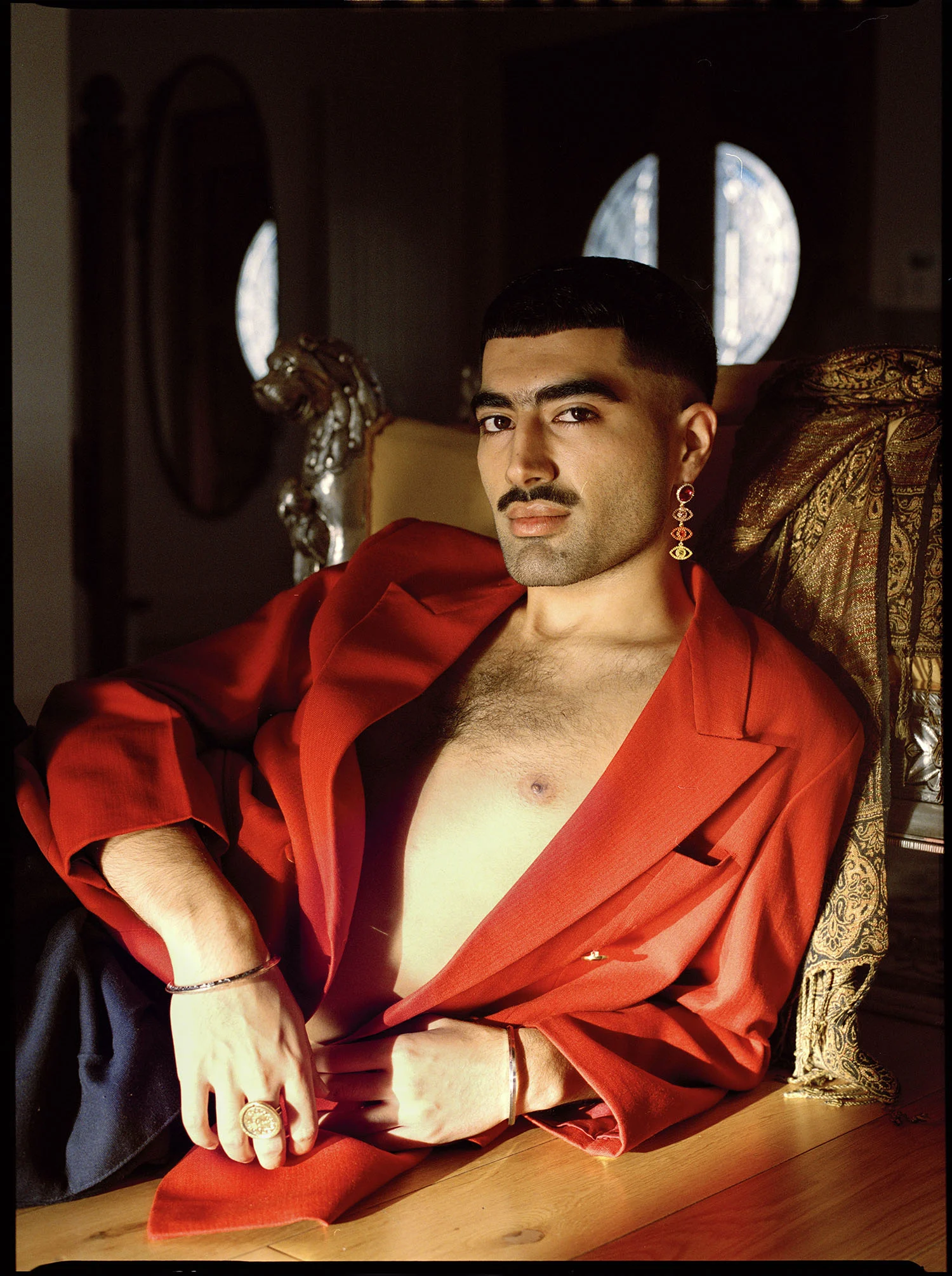

In “Njan,” Kunnath acknowledges the lived experience of her collaborators and how they define liberation—inspired by the work of Sunil Gupta and Nan Goldin. Blending fashion and documentary storytelling, she distorts the lines between reality and fiction, binary and non-binary, conservative and forbidden, in an effort to reclaim power and anchor her community in contemporary visual culture.

It was only through collaborating with the Queer South Asian diaspora in London that Kunnath came to understand the pervasiveness of her culture. “I assumed growing up Queer in the west would be completely different to India, but I discovered that the traditions and mentality are much the same,” she explains. “Geography makes little difference. The pressure to conform remains, and even in the U.K, the community is still underrepresented in culture.”

It's often a life's work to understand how we internalize cultural ideologies and mistake them for our own thoughts, and then engage in the messy work of liberation. Still, Kunnath has been rebelling against these forces since she was young. “I was always aware of the patriarchy, even if I couldn't name it,” she says. “From a young age, girls are constantly judged by how we dress, our skin tone, who we socialize with, how we talk, even how we walk! In Indian society, we live in joint families, so your life is not just shaped by your parents' opinion—it could be your aunt, uncle, neighbour or teacher—everyone has an opinion on your life. As you get older, everything becomes framed around whether someone will marry you. There’s a lot of social pressure, and rules that oppress young people trying to understand who they are. I desperately craved the freedom to explore myself, but it felt impossible when you always have eyes on you.”

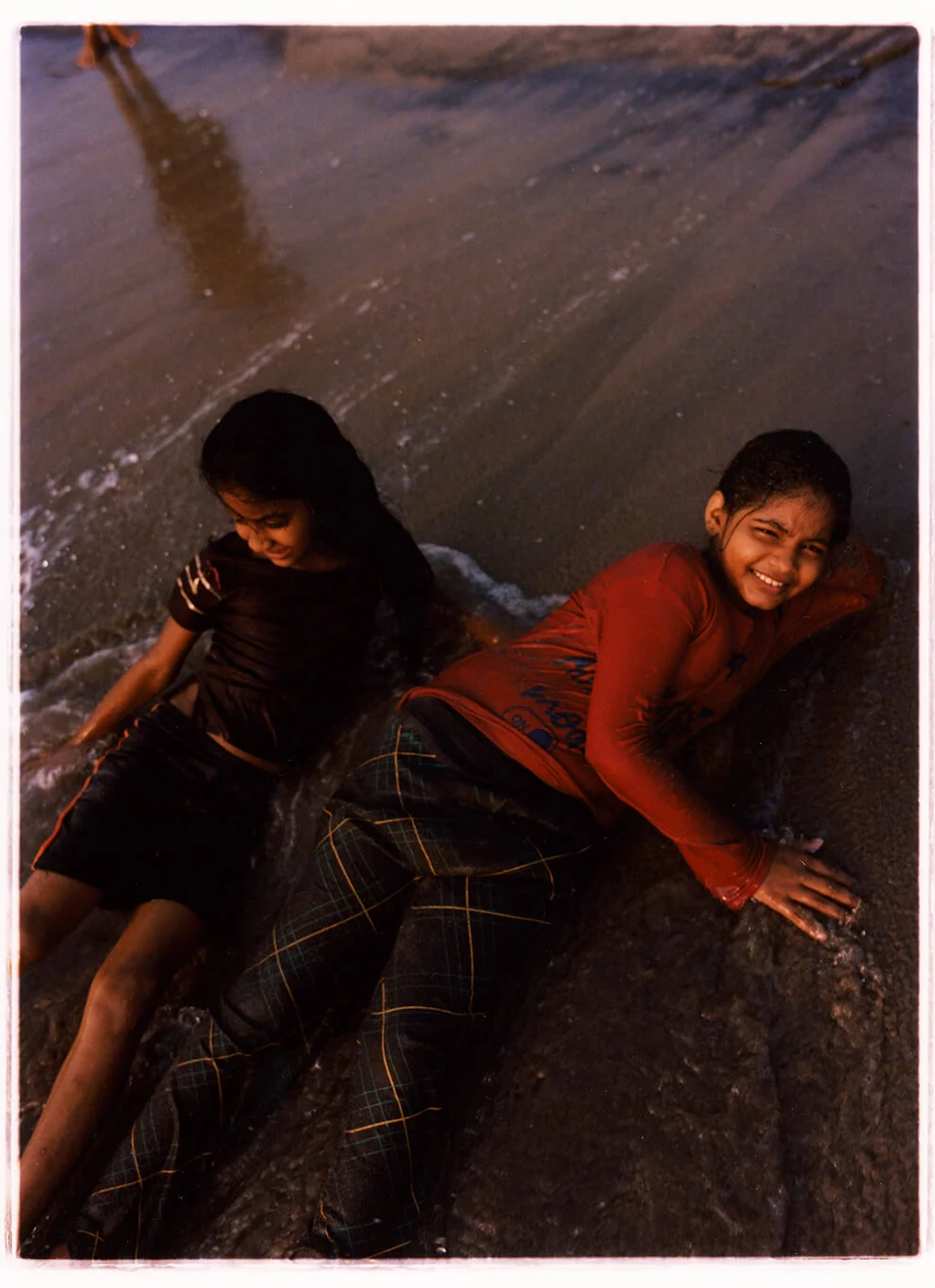

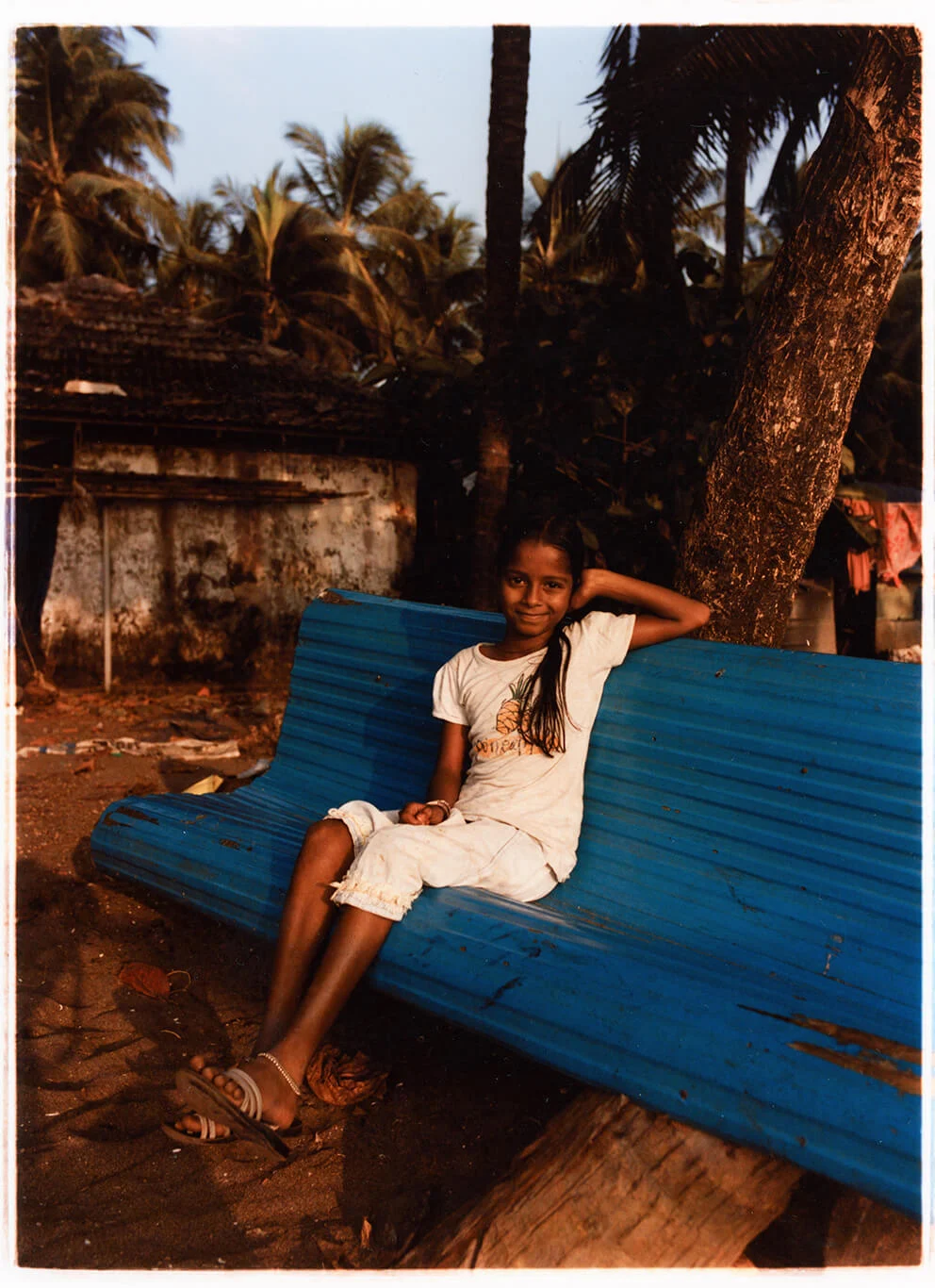

In a deeply personal gesture of repair, Kunnath revisits this weight of oppression in her project “Naddu” (meaning homeland). Set against Beypore’s lush palm-lined landscape, she unravels the painful paradox of not belonging to the place you call home. The series honors the trials and tribulations of her younger self, feeling torn between the pressure to fit into the conservative belief system, where gender determines what you do and how you live, and following her intuition and creative aspirations. While haunting, the work reaches back across history, emphasizing Kunnath's newfound strength and agency.

“Everything I create is for my younger self,” she tells me. “When I grew up in Beypore, I didnt know much about the outside world, but if I hadn't fought for freedom, I know I'd be married and living the traditional life. I never thought this creative life was possible. Now that I know it is, I want to use my platform to encourage young women to question the system and find their path.”