Kathryn Mecca’s paintings are “purposely vague”—they offer zoomed-in looks at body parts and the clothes they adorn. For her, she’s always seen more clearly when less information is offered, and in turn she offers us scenes that are universal, for us to read into ourselves. Emma Firth speaks to her about the everyday voyeurism that inspires her work, and asks how she manages to find the myth and magic of everyday moments.

This is a feature made in collaboration with Platform, a site that offers people the opportunity to easily buy artworks from some of the most exciting contemporary artists in the world. We work with them each month to highlight one of their selected artists.

There’s an Instagram account I frequent often. It’s called @subwayhands. As the name would suggest, it’s essentially a photographic archive of tender hand gestures—sometimes alone, sometimes not—whilst on a frenetic subway train. Someone could be reading bell hooks, holding a bag of ripe tomatoes, holding hands (or themselves). You don’t know who these people are, what they do, where they’re going, and frankly, you don’t need to; the lack of context is what makes the image so superbly absorbing.

“I love that!” New Jersey-born, Maryland-based oil painter Kathryn Mecca tells me. It's an experience the artist is intent on capturing in her pieces, this layer of innocent, everyday voyeurism. Magnifying those quiet, private moments of intimacy, or lack of. “[I need] less information for me to be able to see more clearly,” she explains. “I like to take those small, seemingly subtle, unimportant moments and make them feel very grand and important,” she says, before concluding, “but mostly very dramatic.”

Studying in Rome for a year as part of her MFA programme at Temple University had a profound impact on her subject matter, cropping in a particular feature of the body and the often augmented folds of fabric. “I adore medieval Italian art, the over stylized figures, the strange fabric depictions; it feels so odd. There’s a surreal quality to it,” she says, and she also admires the “Italian’s sense of detail,” where there’s almost a choreography to touch; where casual greetings and elaborate gestures feel “purposely done” and put together.

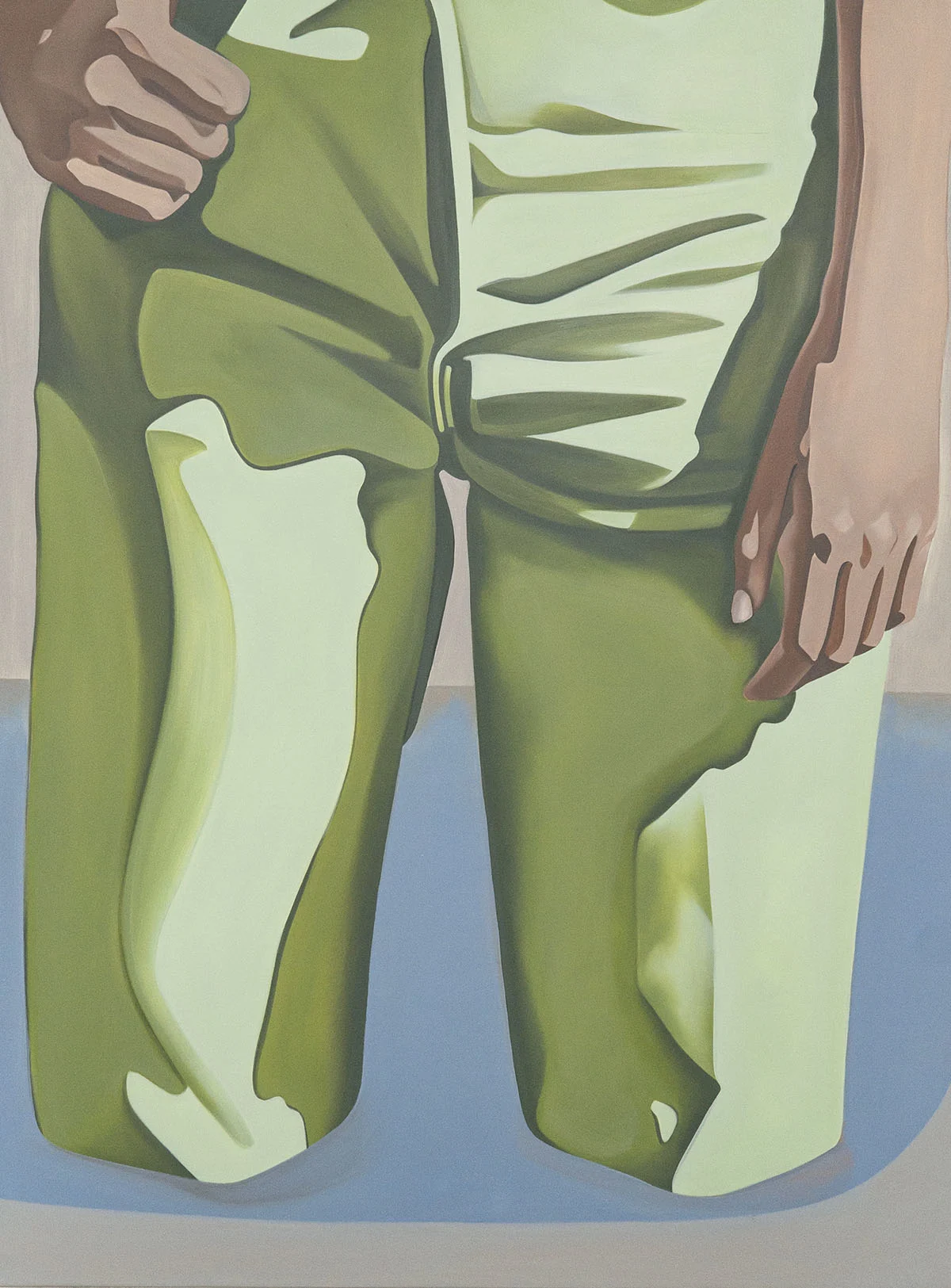

The more you look, the more Mecca’s image transforms, the more you notice a kind of tension—combining fluid fabrics with a lack of gravity, say, or a rigid stiffness in the body. In “Raised Sleeve,” a figure’s hand appears to be reaching for something behind her. A person? An object? “It’s purposely vague,” Mecca says, laughing at my request for a definitive answer. “I like to keep [my paintings] lacking narrative, I don’t like to get too specific with my subjects. It feels more universal.” In “Three Arms,” the connection of the upper arms, the almost familial placement, makes me imagine two sisters or old friends, sitting next to one another in comfortable, routine silence. This combination of physical closeness and disconnect is viscerally apparent in “Green Pants”: a person is standing in water but not interacting with it (“it doesn’t follow the laws of physics.”)

Rather than drawing directly from life, her compositions are born from a desire to distort perception. Before sketching, for instance, she’ll collect reference photos found on the internet, or photos she’s taken out in the wild (“I use my phone camera as a bit of a diary, it’s like writing a note to myself”), as well as staged photographs taken underwater (“it makes the fabric land is a strange way”).

“I like to play with this artificial light source,” she adds. “There’s a cinematic aspect to it. I couldn’t list a movie [that’s inspired] my work specifically, but there is something that is informed by the lens.” The crisp, ultra-sleek lines and intense crop is countered with a soft, distinctly unmoody, color palette—all warm greens, dusty pinks and mushroom greys. Like a photograph that has faded in the sun.

A word that crops up a lot describing her work? Illusion. For many years she worked as a graphic designer in advertising, a language constructed to sell you and I a version of intimacy. The kind of people we could be. A shiny and hyper-curated lifestyle. The most powerful advertising images—shared on social media accounts, our desktops, on the side of buses, on tube platforms—seduce. They keep us looking, and at the same time there is a dissonance, a feeling of detachment. “As a viewer I really like to play with that balance, kind of hovering between the two,” she says. “I love the indulgent smooth flat surface. It feels luxurious, but also cheap.”

In one of the more abstracted pieces as part of a series, “New York in Solomons No.2,” our eyes are fixed on the folds of a trouser suit whilst in motion. “There’s an element of drama, like, what’s about to happen? It gives this sense of movement.” Though, as Kathryn says, she’s careful not to make the focus about fashion per se. “It’s more about how we fashion ourselves, how someone carries themselves, how they present themselves.”

Platform

This is a feature made in collaboration with Platform, a site that offers people the opportunity to easily buy artworks from some of the most exciting contemporary artists in the world. We work with them each month to highlight one of their selected artists.