WePresent has partnered with the Barbican to co-commission Sierra Leonean artist Julianknxx's new multimedia film installation “Chorus in Rememory of Flight.” For this piece of work, the artist traveled around Europe, exploring largely untold stories of Black and African diasporic realities and collaborating with local musicians and choirs. The project will be on show in The Curve gallery at the Barbican, London from 14 September 2023 to 11 February 2024.

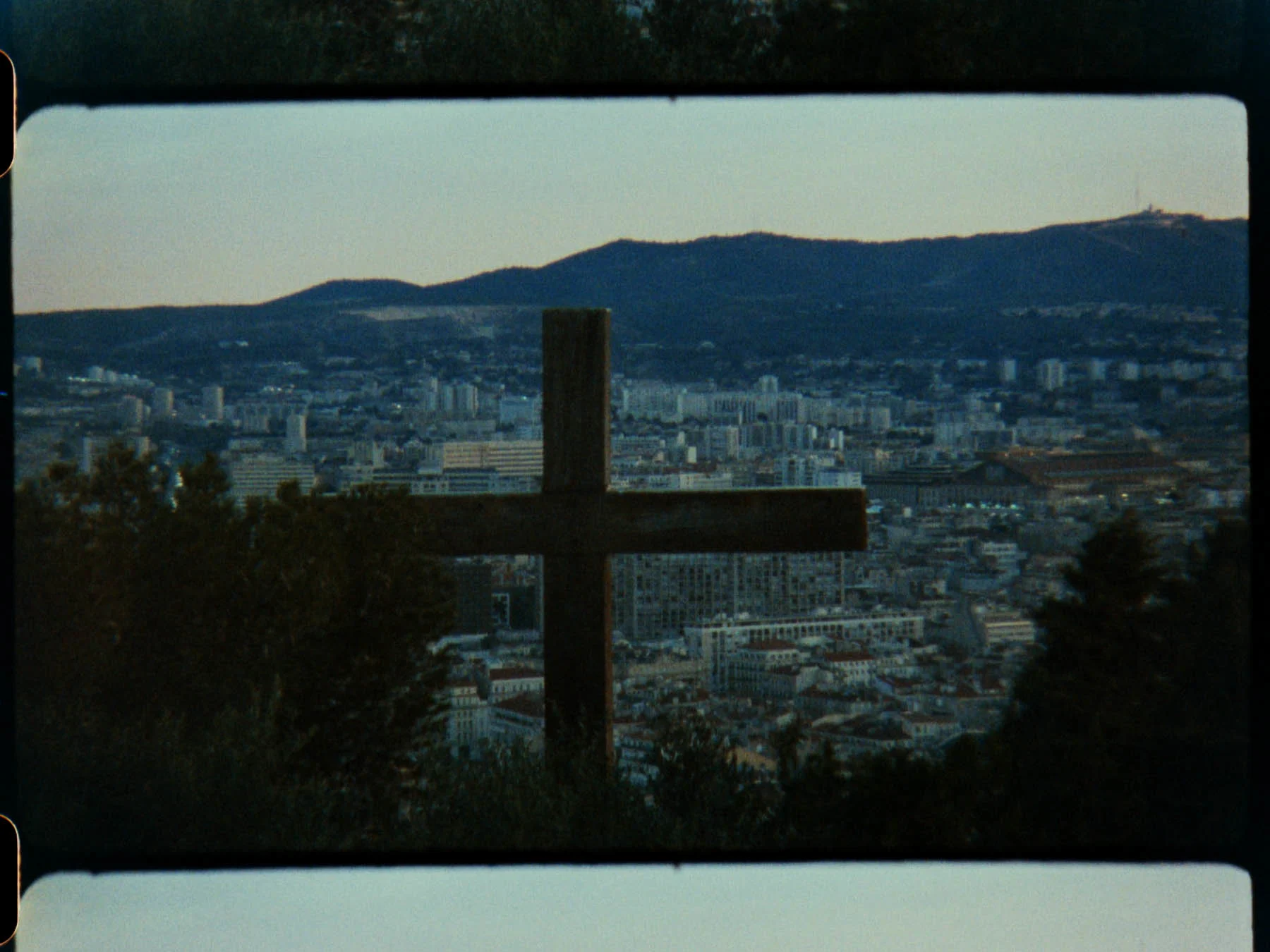

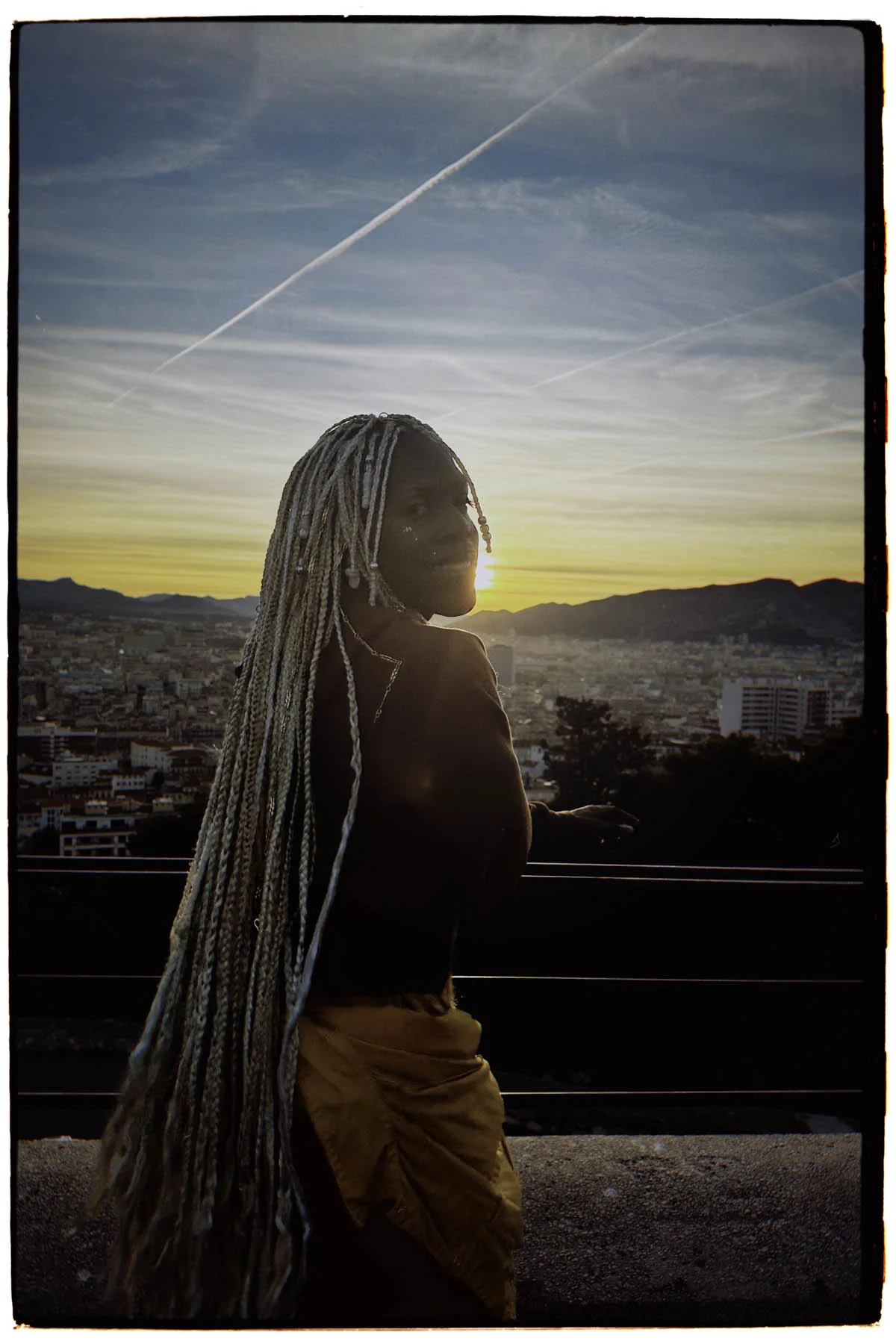

In this part of his European journey, Julianknxx traveled to Marseille. Writers Debo Amon and Abigail Nkaly explore the untold history of this area of France.

The waves playing a melody that only she knows. She dances, sacred,

blending earth, air, and water, revealing the circle of time, as she folds history

— Julianknxx

In 1775 Marie-Cessette Dumas heard word that her son would be taken to France by his father, the man she was currently enslaved to and he would be selling her and her daughters to a baron. Dumas lived in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, now known as Haiti, as an enslaved African woman who had more taken from her than most of us can possibly imagine. I would love to write endlessly about her life, to glimpse the world through her perspective but the little we know of her is recorded in two documents, one confirming the “purchase” and “selling” of her, the other, confirming the “ownership” of her.

So what of the place Dumas found herself? In the 18th Century, Saint-Domingue was considered as the greatest asset in the French colonial empire, as slave-labor was used to produce 40 percent of all the sugar and 60 percent of all the coffee consumed in Europe, which helped France surpass Britain in trade. Through its port city of Marseille, France engaged in a process of extraction from their colonial empire to France itself. Even after the Haitian revolution and following independence, France decreed, in 1825, that it would only recognise an independent Haiti if 150 million francs were paid to it. Haiti agreed but this was likely because France sent a squadron of 14 brigs carrying more than 500 cannons to the “negotiation”. This resulted in a debt not completely paid off by Haiti until 1947, and is a direct cause of an underfunding of education, healthcare and public infrastructure in the country.

But what of the boy born into slavery, then taken from his mother to a foreign land? It seems Dumas knew little to nothing at all of her son, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, once he was taken to France. Maybe she would have felt pride to know he rose through the ranks of the French army to become the first of African descent in the French military, to become brigadier general, divisional general and general-in-chief of a French army. Perhaps she would have been happy to just know of his survival and ignored bitterness that might arise from knowing he was working so hard to prove himself by helping to continue building the country and system of her oppressors.

Maybe she felt a knowing sorrow, as she was well aware of what it meant to be cast aside by a society or someone who no longer needs you and never really loved you—an experience reflected in her son’s later years, when he was abandoned by Napoleon and denied his pension, plunging his family into poverty. Would Dumas’ sorrow have deepened if she had known that her grandson, Alexandre Dumas, would also be subject to ridicule and racism, despite being one of the most prolific and widely-read French authors and playwrights of all time.

It’s too easy to categorize these periods in European history as moral injustices but that ignores the material contribution, whether forced or given, of African and Black people’s labor, culture and resources to European wealth, society and infrastructure. Dumas was part of a cycle of brutality and exploitation that enriched and helped build France and particularly its second city, Marseille, the hub through which the French empire operated. Whether or not recorded, her contributions, and the plethora of those like her and her children, grandchildren and so on, are carved indelibly within the stones of Marseille. A city that was built, rebuilt and rebuilt again on the contributions of African and Black people and cultures. Perhaps Dumas, or what she represents, is the mysterious figure in Julianknxx’s opening poem, her history informing our present, helping those of us who care to look to see what was taken, what we have given and what we brought with us, to these cities we now call home.

“We need to teach our stories to ourselves,” says writer, artist, Black Marseille tour curator and American in Marseille, Martin Grizzell as he speaks to Julianknxx about the impact of being able to read himself and his heritage into Marseille and its shores:

“So here [it] was the first time that I’d gotten into the sea since I was like eight or nine-years-old. I got caught in an undertow and was taken out to sea and brought back and nobody knew I was even gone. From then on, I didn’t deal with the sea. When I got here, it took almost a year for me to dip my toes in the Mediterranean. That was the beginning of my healing process and when the idea that: somebody in my line missed Elmina, Ghana, which is where I think we came out of, the castle that my descendants, ancestors came out of. Somebody didn’t get caught there and got here. Because when I tried to get into that sea, I had all of these ghosts and memories of things that I had read and hallucinations about what happened on the Atlantic and what happened on this sea because the Arabs had trade going on here 800 years before the Europeans. So something happened with my people on this sea and I had to go through them to get into the sea, to swim in it.

That process was a healing piece for me. It also opened the door to the possibility that, OK, if history is a recurring event on some level, then something happened to me and to my lineage on this sea, and from then, I was able to heal, and I was able to begin to see the many African influences in Marseille.”

Inheritance is for women. It’s matriarchal. In our culture women pass on. They pass on culture.

— Fatima Ahmed

What do we sing to our children to teach them of home if our own language and stories are foreign to us? This was an issue that Mbaé Tahamida Mohamed, more commonly known as Soly, came across when he realized that his little sisters didn’t know the lullaby from back home in Comoros. It was then he and his wife Fatima Ahmed embarked on a journey to archive and pass on this heritage by starting a choir of Comorian women. For Comorians inheritance, both cultural and material, is matrilineal. A husband leaves his home and joins his wife—perhaps this way of thinking would make Marie-Cessette Dumas proud, or at least have secured the futures of her daughters. Yet, now these women of the Boras Choir sing more than lullabies, they sing of revolution and their country’s independence from France in 1975, they sing of solidarity and forced marriages, they sing of fields and fishermen, of painful realities, they sing it all to themselves and into the future, through their children.

I don’t understand Comorian, but I wonder what a revolution sounds like passed down through the songs of women who lived it, rather than the generals and soldiers who fought. Ahmed says it’s only right that it’s like this as women carry and care for the children, so of course it would be them who carry and care for their culture. If it’s all in the stone, perhaps these women—Black women—are rocks too. The bedrocks of their cultures, the foundations of their heritage. Even unseen, women such as these have held up children, cultures and countries, unsung while they sing, unheralded while they toil. Nations have been built on their backs but what do they inherit in the place they now call home?

With this in mind, Julianknxx asked Abigail Nkaly, the production and camera assistant during his time in Marseille, if she would like to contribute something inspired by her time working on the project with him. She agreed and a few weeks later she sent this to him in both French and English, a reflection on what it meant for her to experience Marseille anew, through the perspectives of the numerous contributors they spoke to and filmed. It may be too much to say what Abigail found was possibly an inheritance of sorts, but reading her words reminds me that what was taken is not necessarily lost and what we brought with us is for us to share.

Explore Julianknxx’s experiences in the seven cities he visited to make “Chorus in Rememory of Flight”

“Chorus in Rememory of Flight” has been co-commissioned by the Barbican and WePresent by WeTransfer in partnership with Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and with support from De Singel.