For centuries, photography has served as an imperial weapon—a tool used by colonial powers to control, dehumanize and “other.” In her new monograph, “The Fold,” Hoda Afshar confronts this history by reworking thousands of images of veiled men and women taken by French psychiatrist Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault in the early 20th century. Through darkroom printing and digital manipulation, she turns these exoticist photos into a space for resistance. She tells Alexander Durie about the historic and continuing use of bodies—especially women’s—for political ends, and about what it means to reclaim them.

“The Fold,” published by Loose Joints, is available to buy here.

Traditionally speaking, photography, particularly documentary photography, has been thought of as a medium capable of representing reality, of providing a reliable—even objective—narration of the past. But from whose gaze? Capturing which people? Which places? And how? As time went on, though, photography’s inherent subjectivity and its historical ties with colonialism began to be confronted.

This project for me is an excuse to be able to talk about this history, that our bodies are constantly symbolically used for political purposes.

A range of post-colonial scholars, from Ariella Aïsha Azoulay to Ali Behdad, have highlighted how, since its inception, the camera served as an imperial weapon—a way of othering and removing the self-determination of indigenous people, who were often photographed without context or consent.

Behdad notes that “photography perpetuated and amplified colonial and exoticist fantasies, cementing its role as a key factor in the narrative of Western dominance over the East.” Knowledge-building grew from image-making, but from a Euro-centric lens that often served to justify expansionism and the colonial idea that the West was more “civilized.”

It’s through this critical framework that award-winning Iranian-Australian photographer Hoda Afshar embarks upon her photographic projects. Having completed a PhD in Australia “around the representation of the Islamic female body in the visual art world, and the obsession of the West with it,” she is always questioning how and by whom history has been recorded, and the power dynamics at stake.

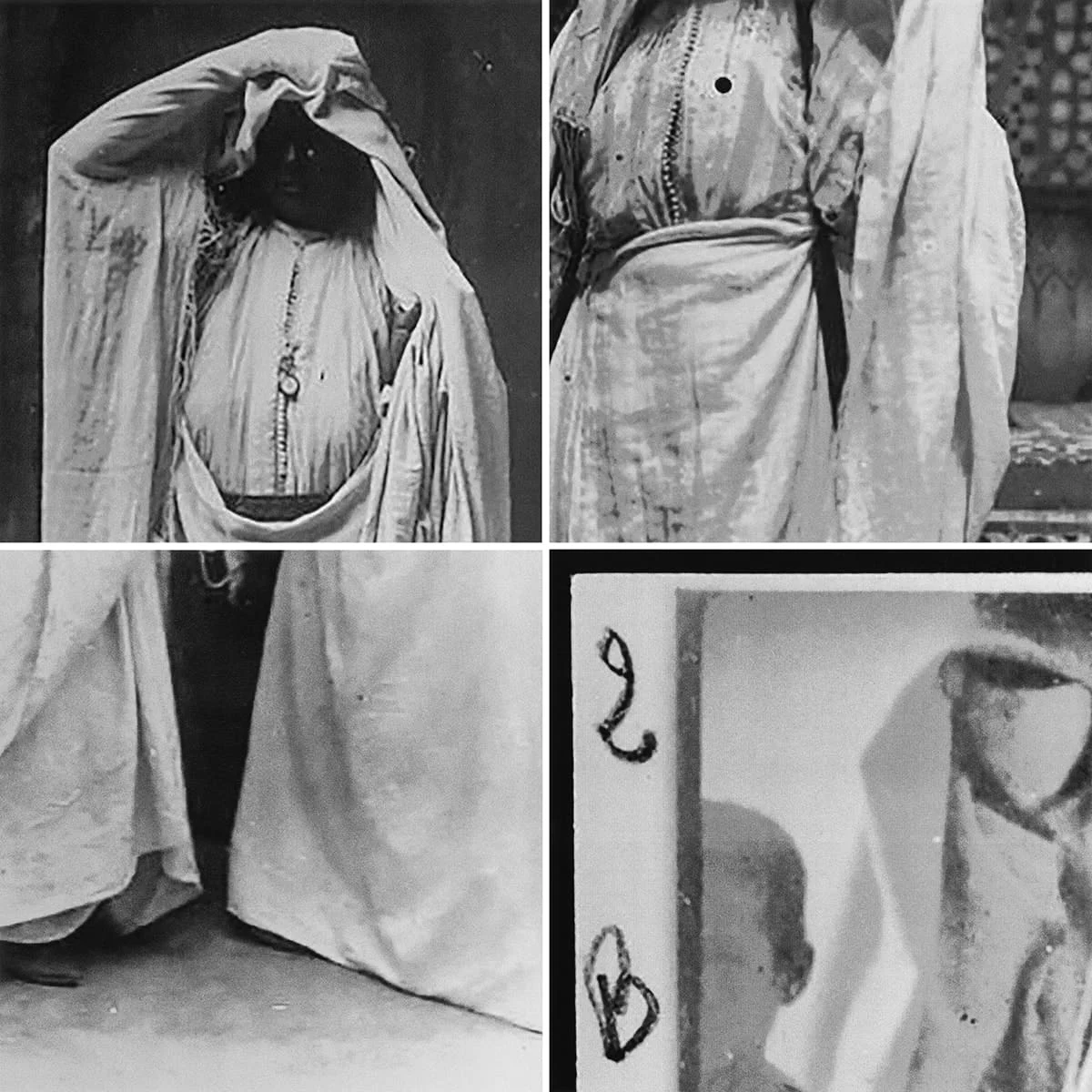

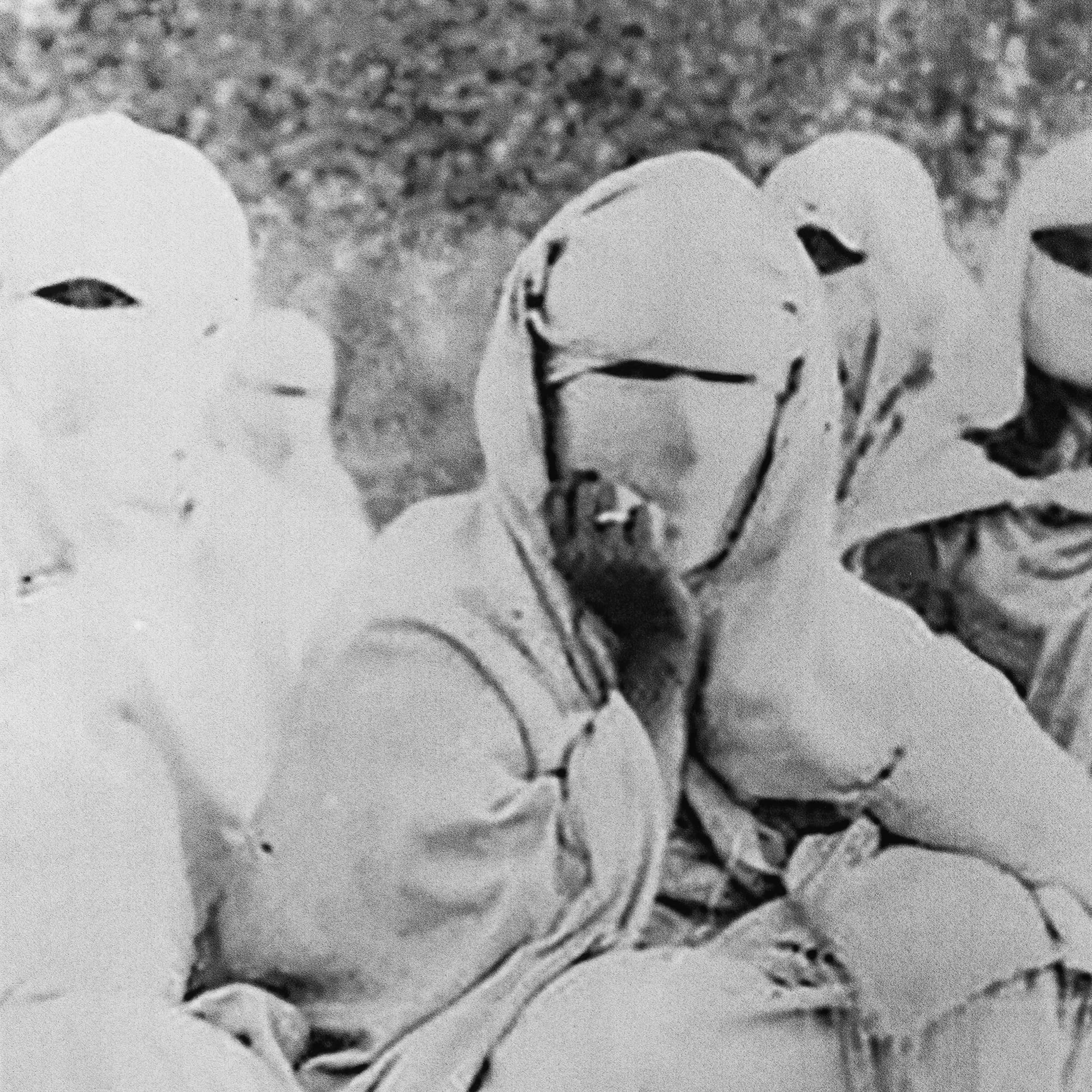

In September 2025, Afshar’s second monograph, “The Fold,” will be published by Loose Joints, to precede her months-long exhibition at the Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac in Paris, running until late January 2026. Both her book and the exhibition explore photography’s legacy as a colonial and Orientalist tool, focusing on the vast archive of the French psychiatrist and photographer Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault, who, in the early 20th century, produced thousands of images of veiled women—and sometimes men—in Morocco.

Afshar is one of the first contemporary artists invited to engage directly with the quai Branly’s archive, an exceptional feat as the museum is, alongside the British Museum in London and the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin, one of the major anthropological museums in the world, housing thousands of looted objects and colonial archives.

The project started in 2019, when Afshar was inspired by the book “Draw Your Weapons” by Sarah Sentilles, which recorded how, during the colonial period, French photographers in North Africa became obsessed with documenting female servants in harems, but couldn’t access these women-only spaces, so they re-created them in makeshift studios. Afshar’s interest in these issues felt personal—being born in Tehran four years after the Islamic Revolution of 1979, which led to a hijab law that decreed it mandatory for all women in public in Iran.

“For as long as I lived in Iran, I was fighting against the patriarchy in my own country, and that was precisely what made me leave and come to the West,” says Afshar, who moved to Australia when she was 24. “I was then confronted with the way that the West treats my body and my image—so this endless battle between both forces is always at the heart of my experience, and it’s definitely one of the driving factors in making this work.”

Afshar embarked on a long research process in the archives of the quai Branly, but it was when the museum’s photography curator, Annabelle Lacour, introduced her to the bizarre yet fascinating collection of images taken by de Clérambault, that something clicked for Afshar.

We have our own grassroots movement… we don’t need you to come and save us. We are capable of reaching our own freedom without you.

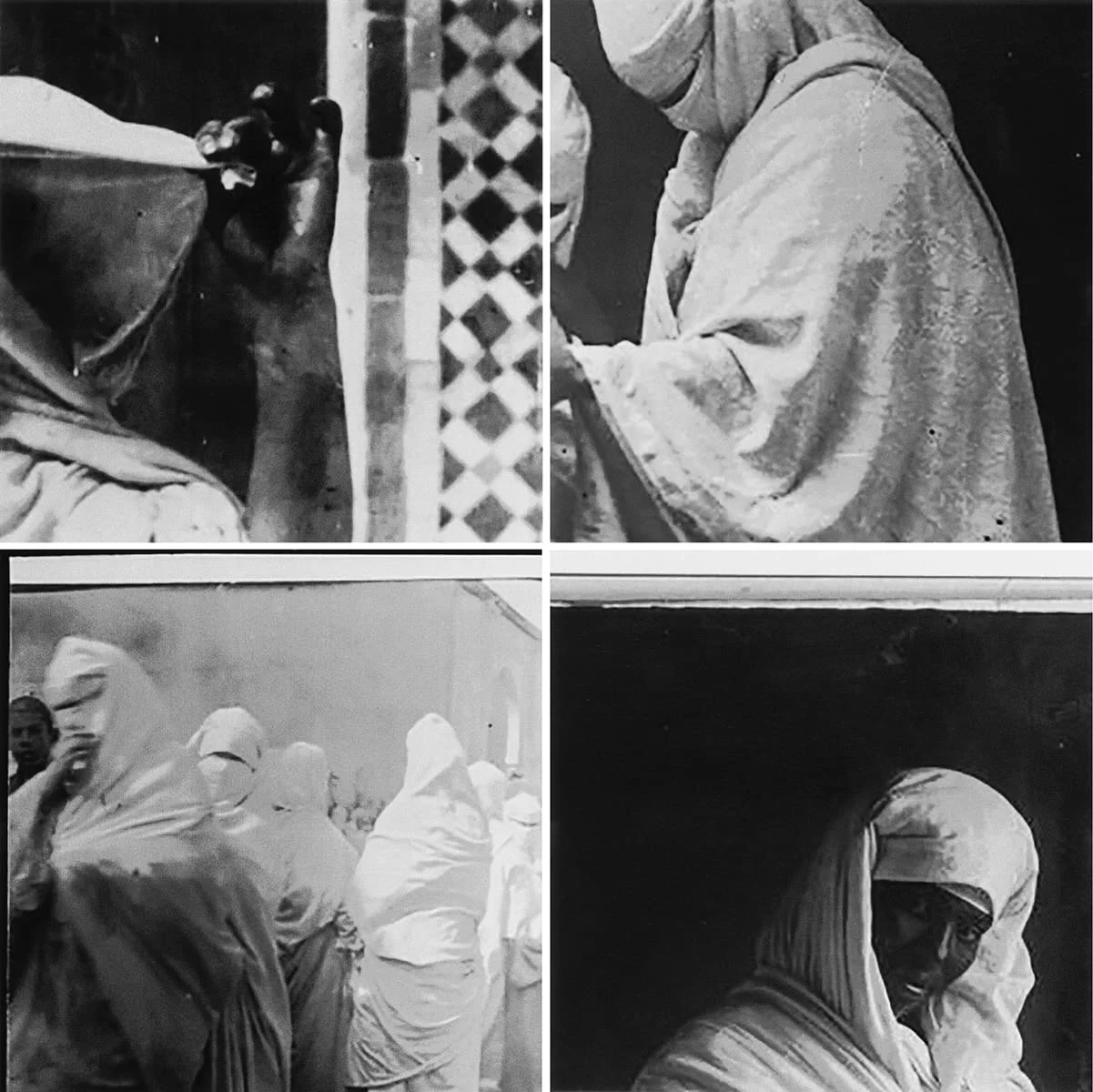

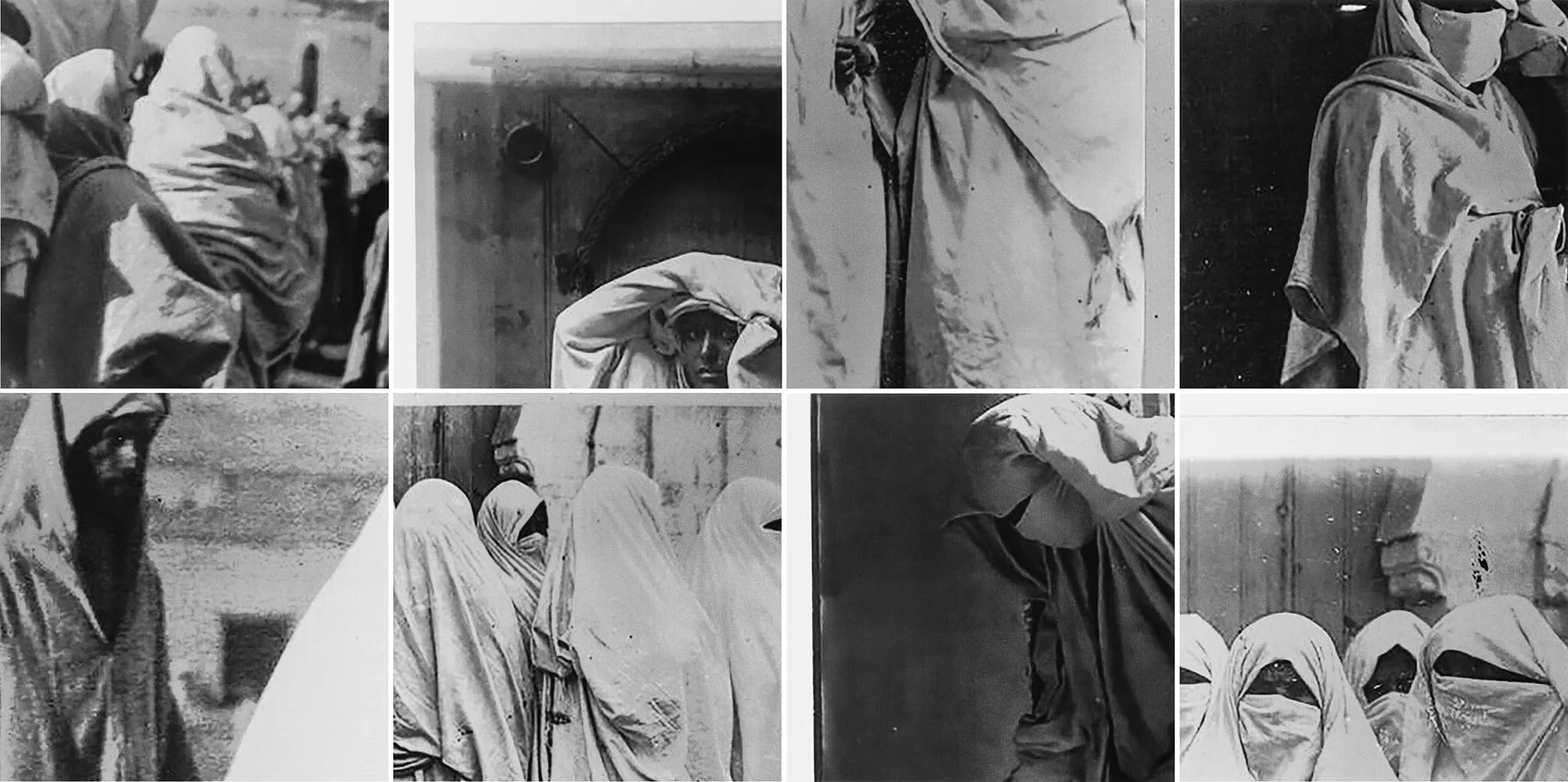

De Clérambault had an almost fetishistic obsession with African women’s fabric and how it folded, particularly the haik (a traditional woman’s garment from North Africa). The psychiatrist-photographer later committed suicide with a revolver to the head in 1934. According to local press, he was found in front of a mirror surrounded by a “strange collection of wax mannequins that he delighted in dressing with rare fabrics.”

“He was the missing part of the puzzle,” Afshar says. “The excess and repetition were very fascinating to me. He made over 40,000 images of the same subject.” Afshar was absorbed by the “relationship between sexual fantasies combined with fear” in de Clérambault’s images—assessing that the “psychology of racism starts with that.”

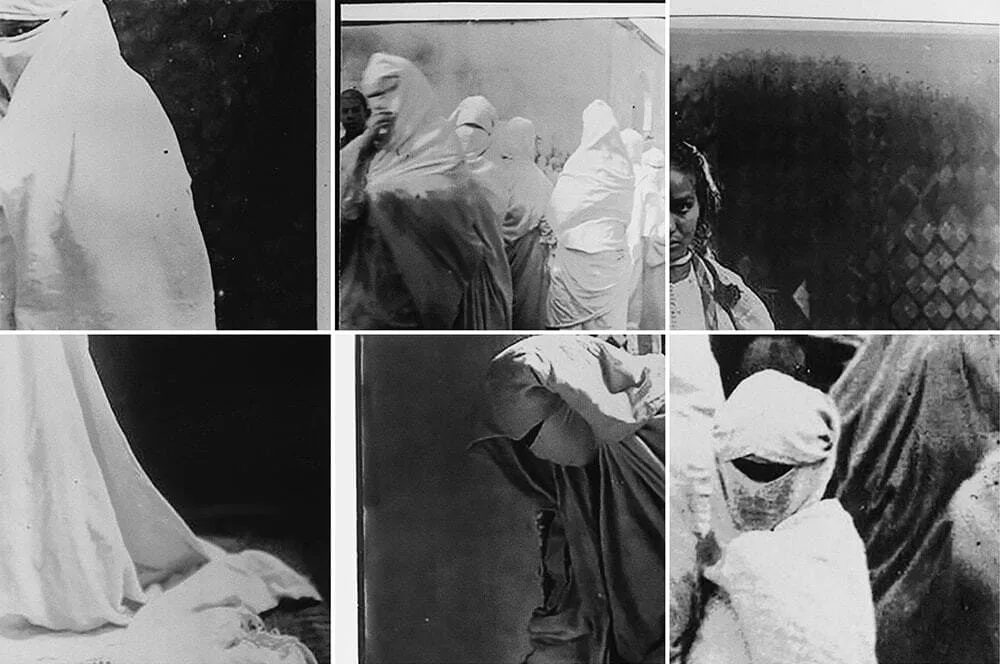

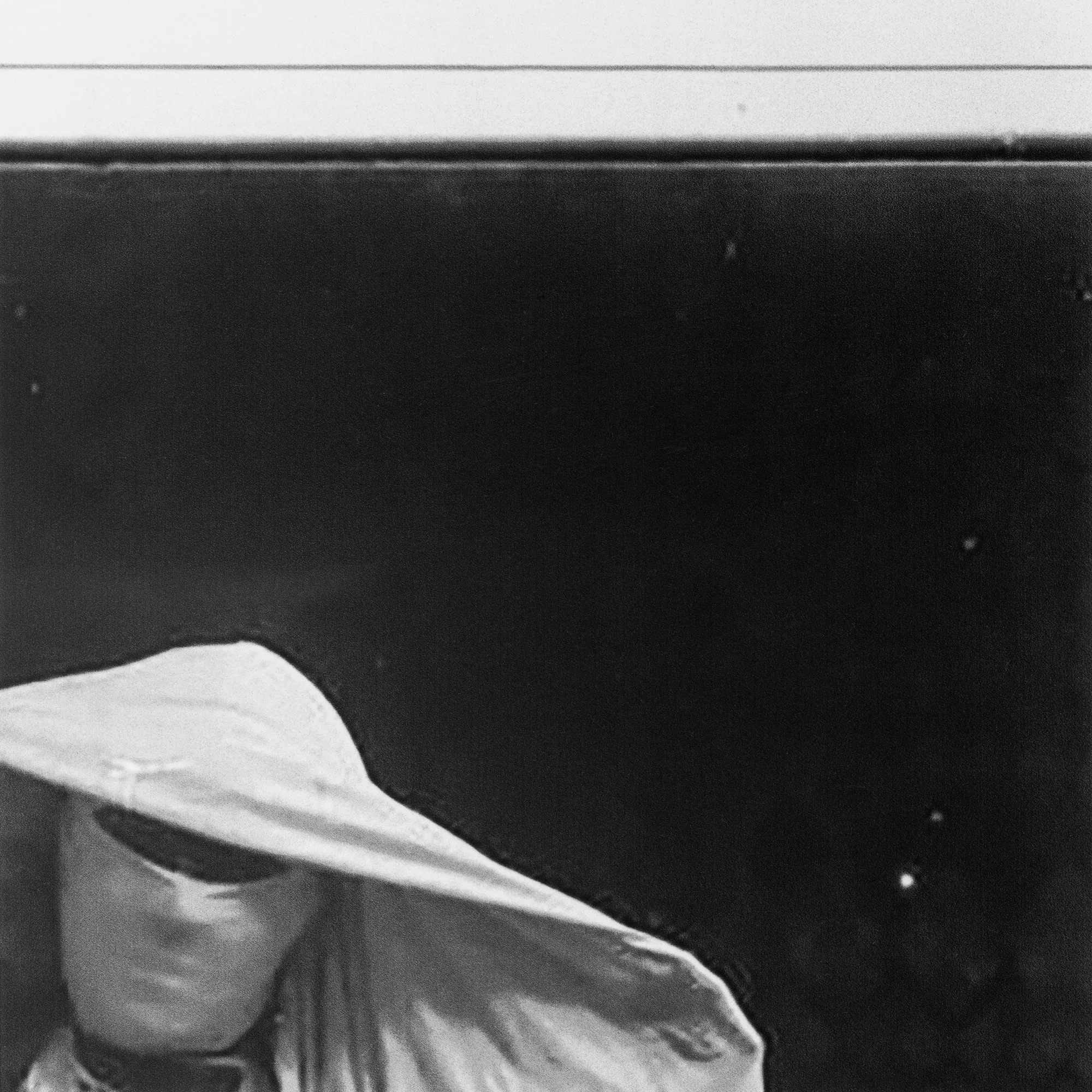

Afshar decided to make this enigmatic figure her subject-matter for “The Fold,” but when she started going through the quai Branly’s archive, she discovered she could only download small, low-resolution square fragments of de Clérambault’s images. “I realized the website is designed to protect the online archive, so when you click on the image and save, it only gives you the tiniest square from the bigger image.” Afshar was first disappointed, but eventually found a way to overcome this technical obstacle.

With a friend running a darkroom in Melbourne, she decided to “take these tiny pixels, upsize them, print them as negatives, take them to the darkroom, and reprint them as an actual darkroom print.” In short, creating negatives from the thumbnails, and then printing them as positives. The darkroom quality was “really important” for Afshar, as it mirrored the original process done by de Clérambault, but in reverse.

By using this practice to deconstruct de Clérambault’s images, Afshar analyses the analyst—reclaiming authorship over these Orientalist photographs, and reversing historical power dynamics. The gaze turns not only towards the ghost of de Clérambault, but towards the viewer. As Ali Behdad writes in one of the three texts accompanying the more than 950 images in this monograph: “‘The Fold’ turns the lens back onto the image-maker himself.”

Afshar insists she’s not trying to present de Clérambault’s images as beautiful. “It’s about the degradation of the image through these processes. The book is about the act of looking, about the looker itself. It’s like an anti-image book,” Afshar explains, saying she wants people “to be annoyed with the low quality of the images, to be puzzled with the repetition and lack of information, and to then realize they’re dealing with a book that is working against the images that are in there.”

Working with these archives, Afshar came to realize that although photographic technology has changed significantly since the colonial period, nothing has changed around the exploitation of women’s struggles. “This project for me is an excuse to be able to talk about this history, that our bodies are constantly symbolically used for political purposes.”

Afshar mentions as examples how old photographs of Afghan women with miniskirts were used to push for the US invasion of Afghanistan—claiming they were “freeing” Afghan women, and how, last June, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu uttered the famous slogan of the 2022 uprising in Iran, “Woman, Life, Freedom,” to assert that Israel’s attacks on Iran aimed to “clear the path” for Iranian women.

“We sacrificed so much, and to see that movement being hijacked again by these men is the most heart-wrenching thing to see,” Afshar says. “We have our own grassroots movement. We have fought for it for decades, and we don’t need you to come and save us. We are capable of reaching our own freedom without you.”