Following our 2023 Guest Curatorship with Russell Tovey, in which we explored the legacy of artists lost too soon during the AIDS crisis, WePresent has partnered with Talk Art and the Whitechapel Gallery to examine the life and legacy of artist Hamad Butt with curator Dominic Johnson and Hamad’s brotherJamal Butt, in light of the critically acclaimed exhibition currently on display at the London gallery. And for the first time ever, Jamal allows us into his home to photograph some of his late brother’s never-before-seen artworks, while opening up about Hamad’s life and inspirations to Russell Tovey and Robert Diament on this special episode of Talk Art.

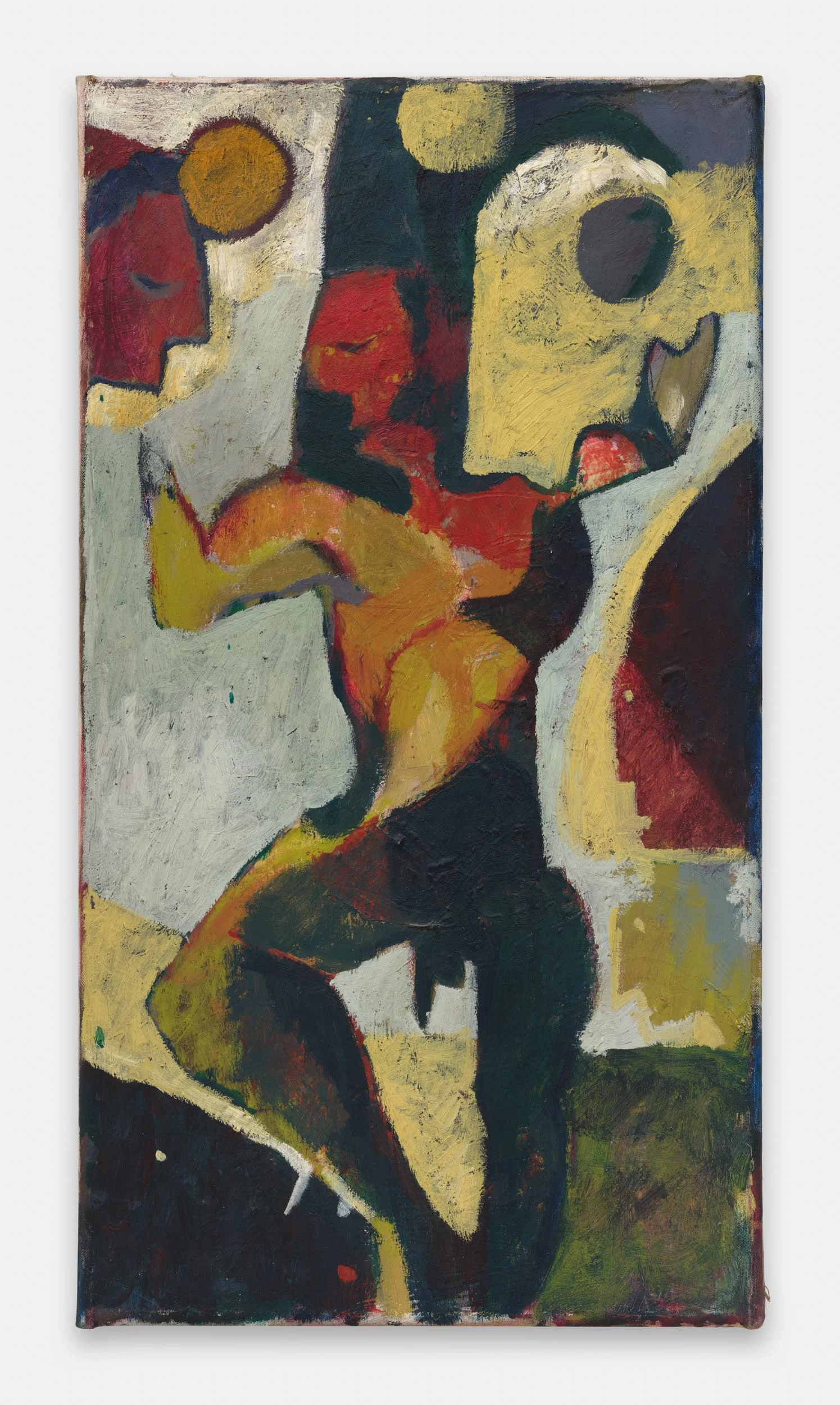

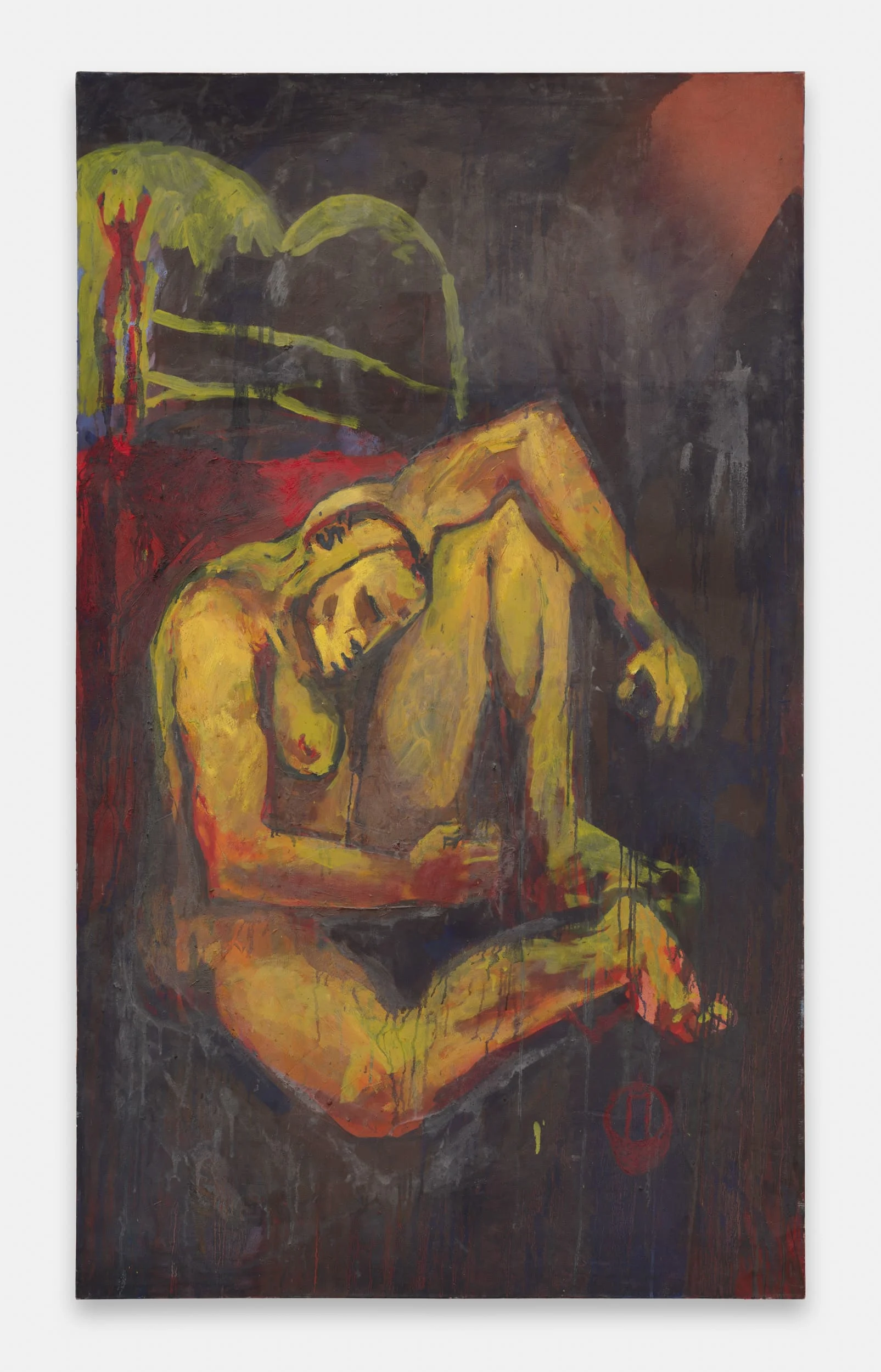

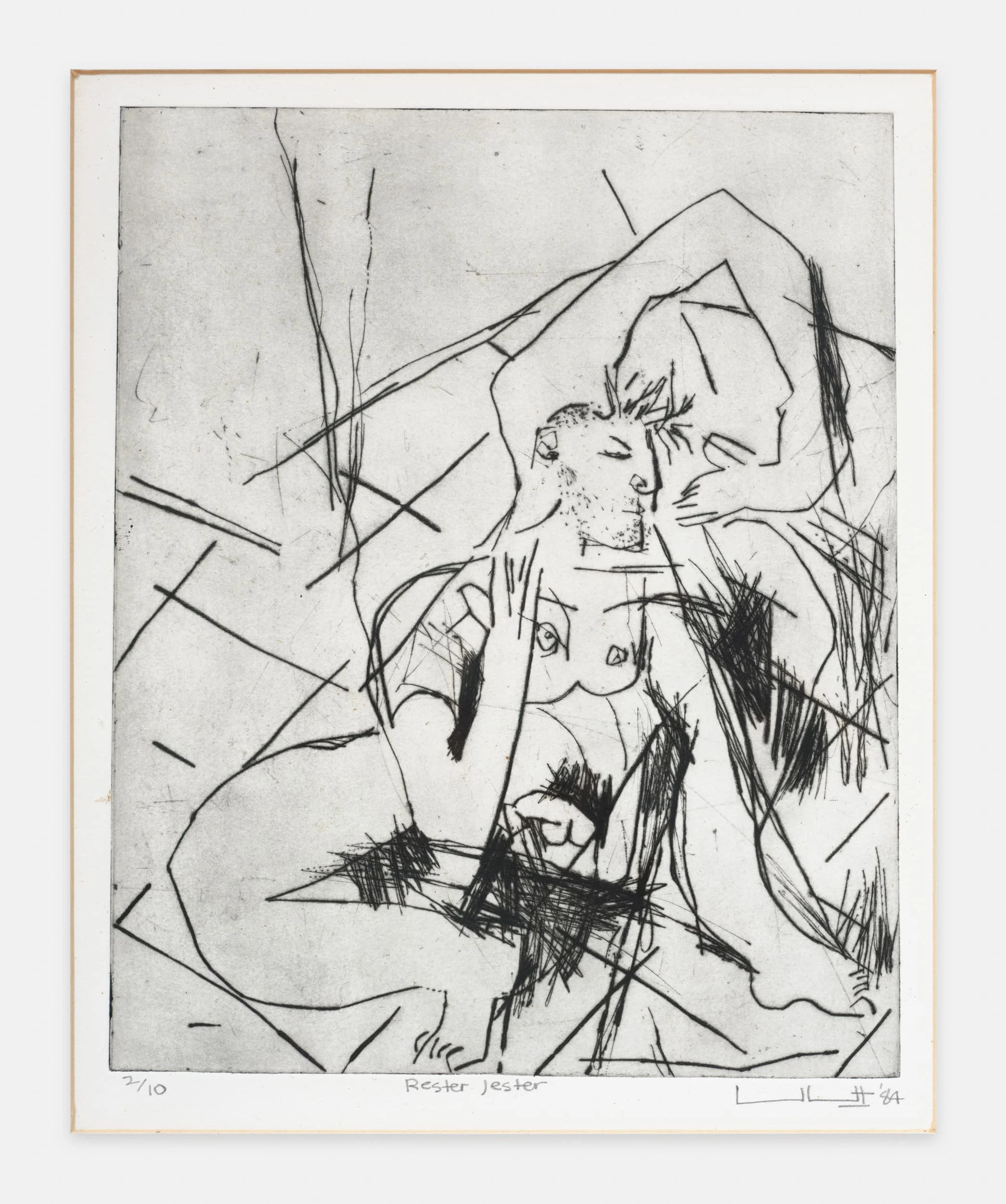

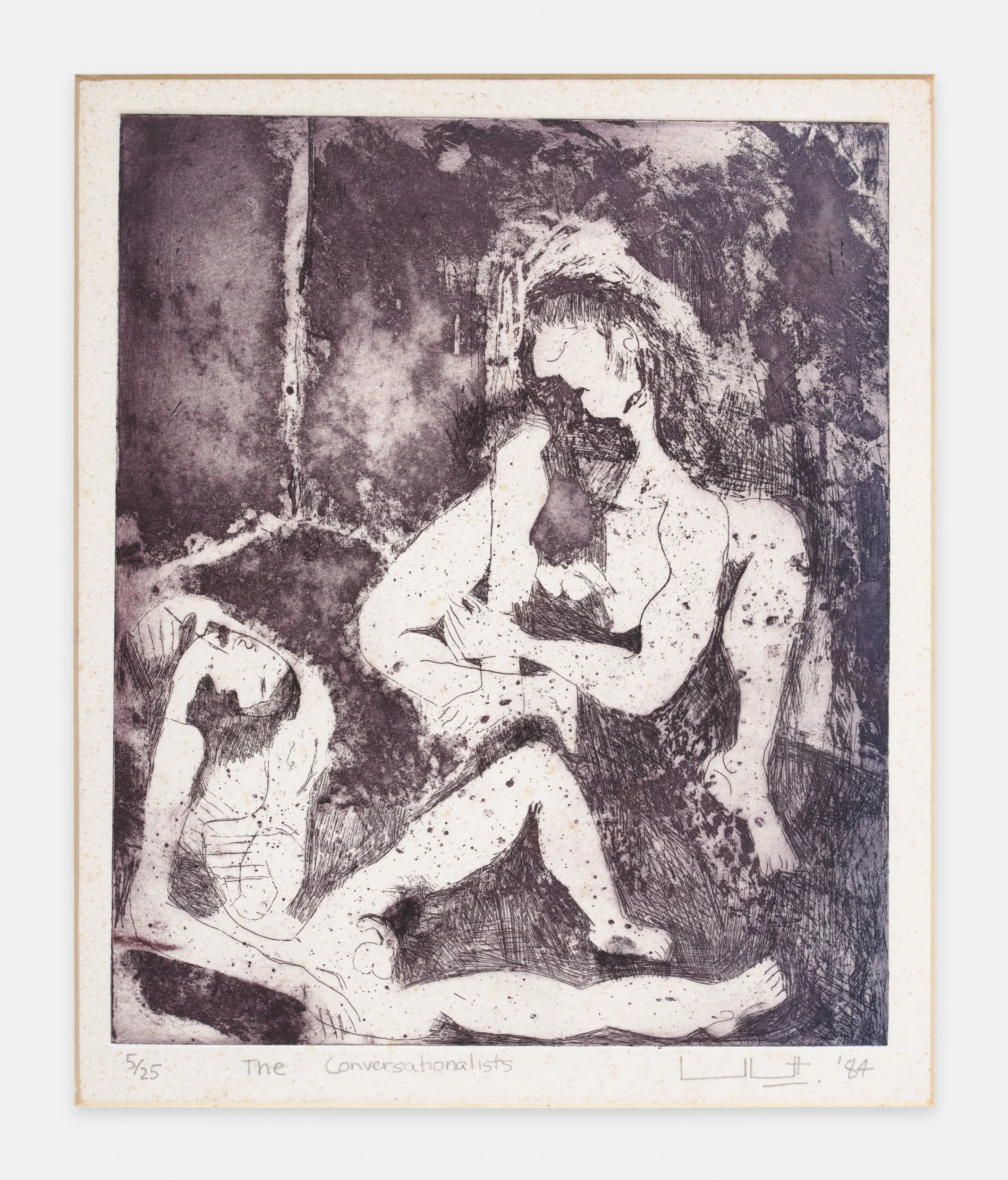

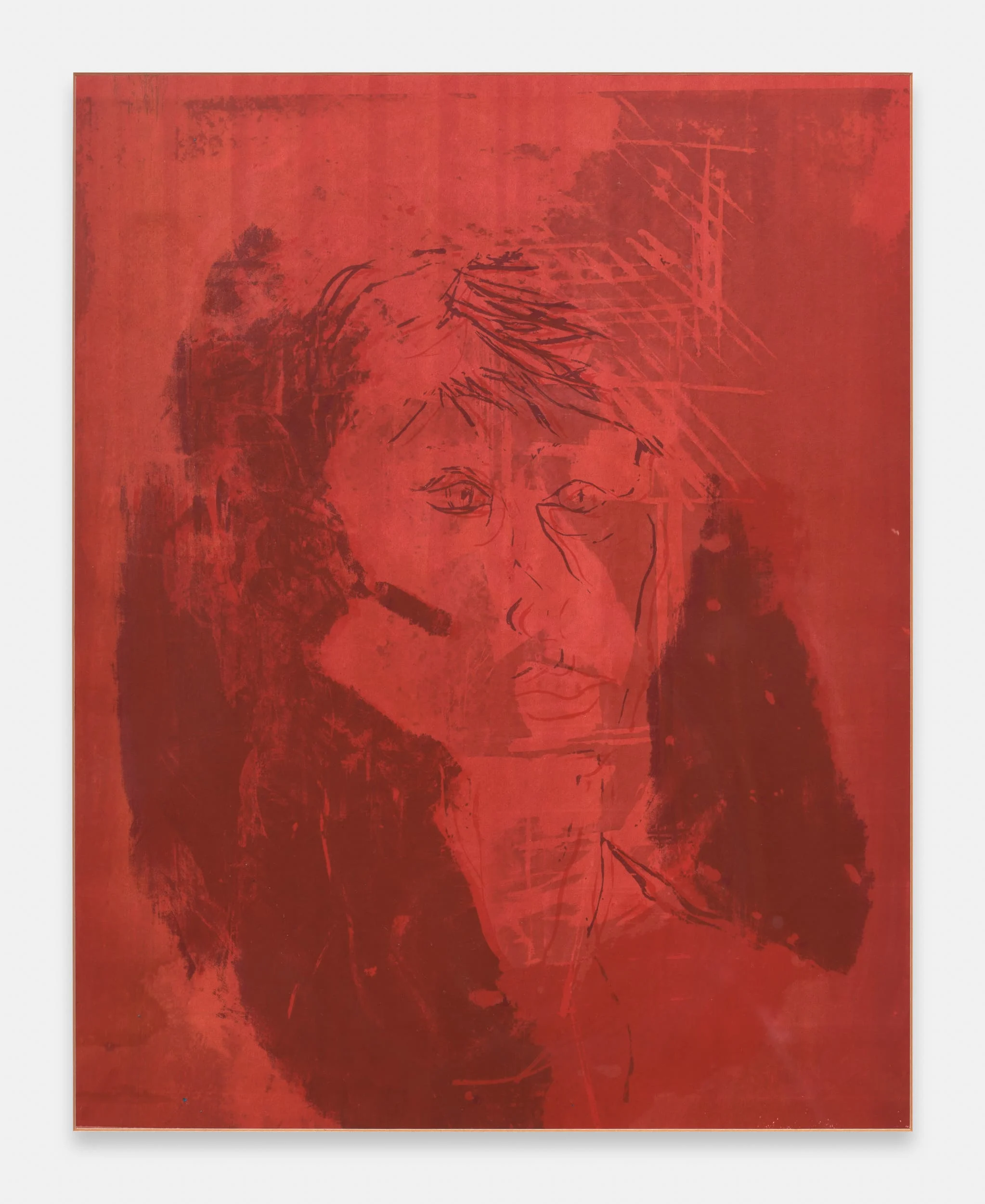

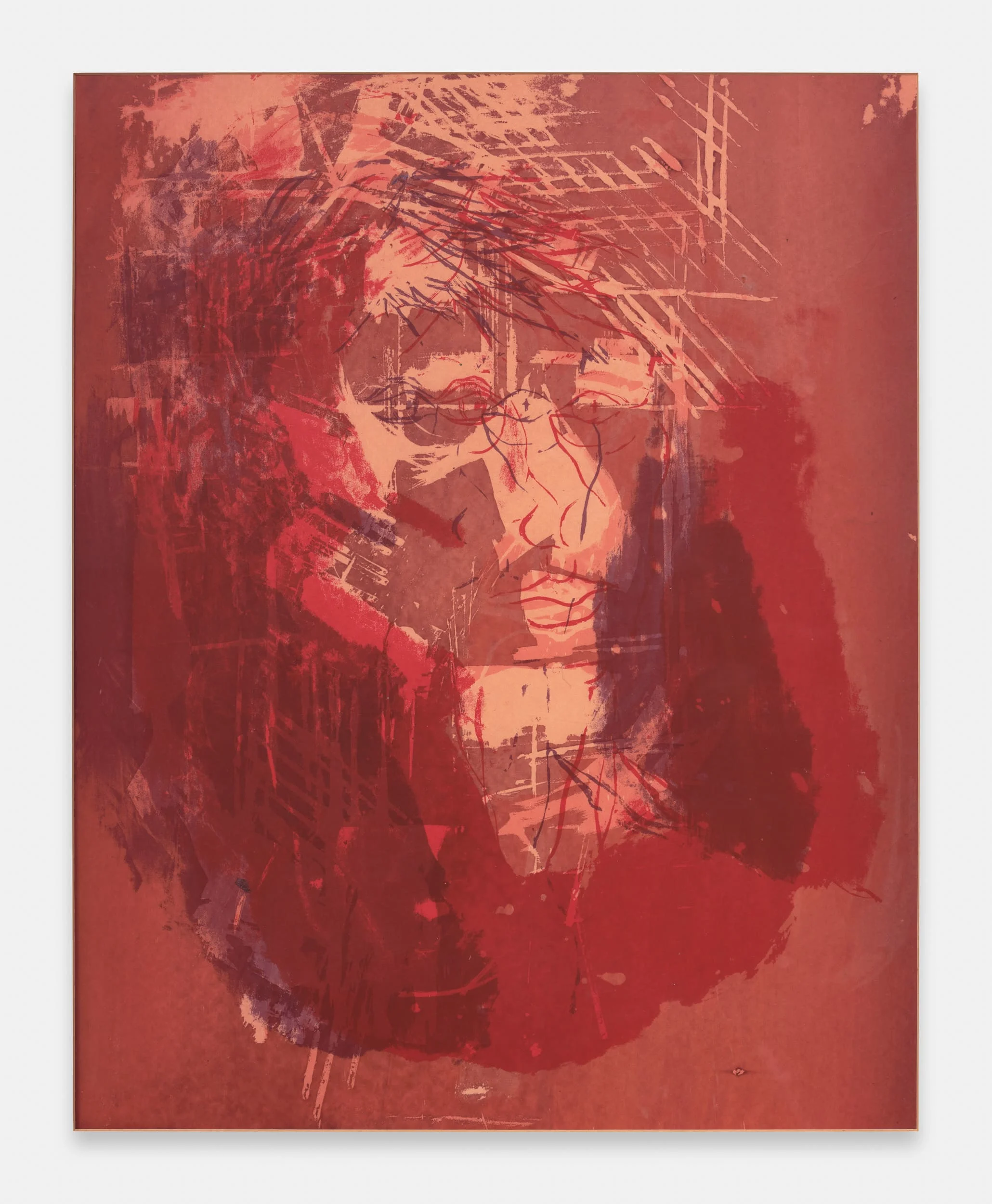

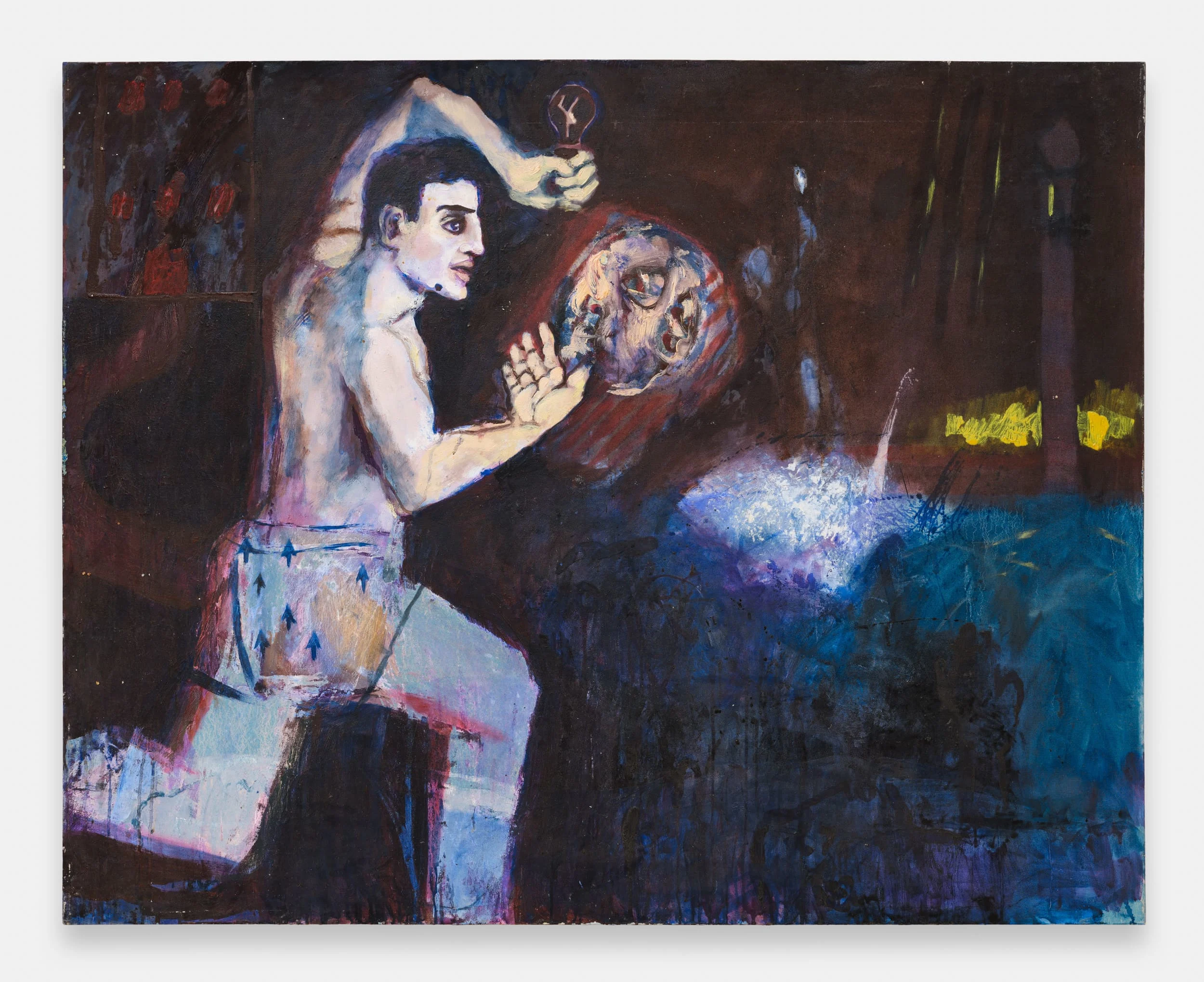

All paintings and drawings courtesy of Jamal Butt, photographed by Eva Herzog and Aggie Cherrie.

When Hamad Butt emerged in the British art world of the early 1990s, his work felt like an electric charge—delicate, dangerous, and deeply alive. Born in Lahore, Pakistan in 1962 and raised in the UK, you may not be instantly familiar with his name—the artist died in 1995 of an AIDS related illness—but while his life was brief, it was piercingly impactful. In his 33 years the artist carved a singular path that would not be properly appreciated then, but is now finding new prominence in the art world, and with a whole new generation of art lovers interested in the intersection of identity, science, and poetics that has come to define his practice. His work in the 1990s—rooted in early explorations of bio-art with materials ranging from glass to light to chemicals—was some of the most pioneering at the time, and a new exhibition currently on display at Whitechapel Gallery in London is now bringing this artist’s name rightfully back to mainstream attention.

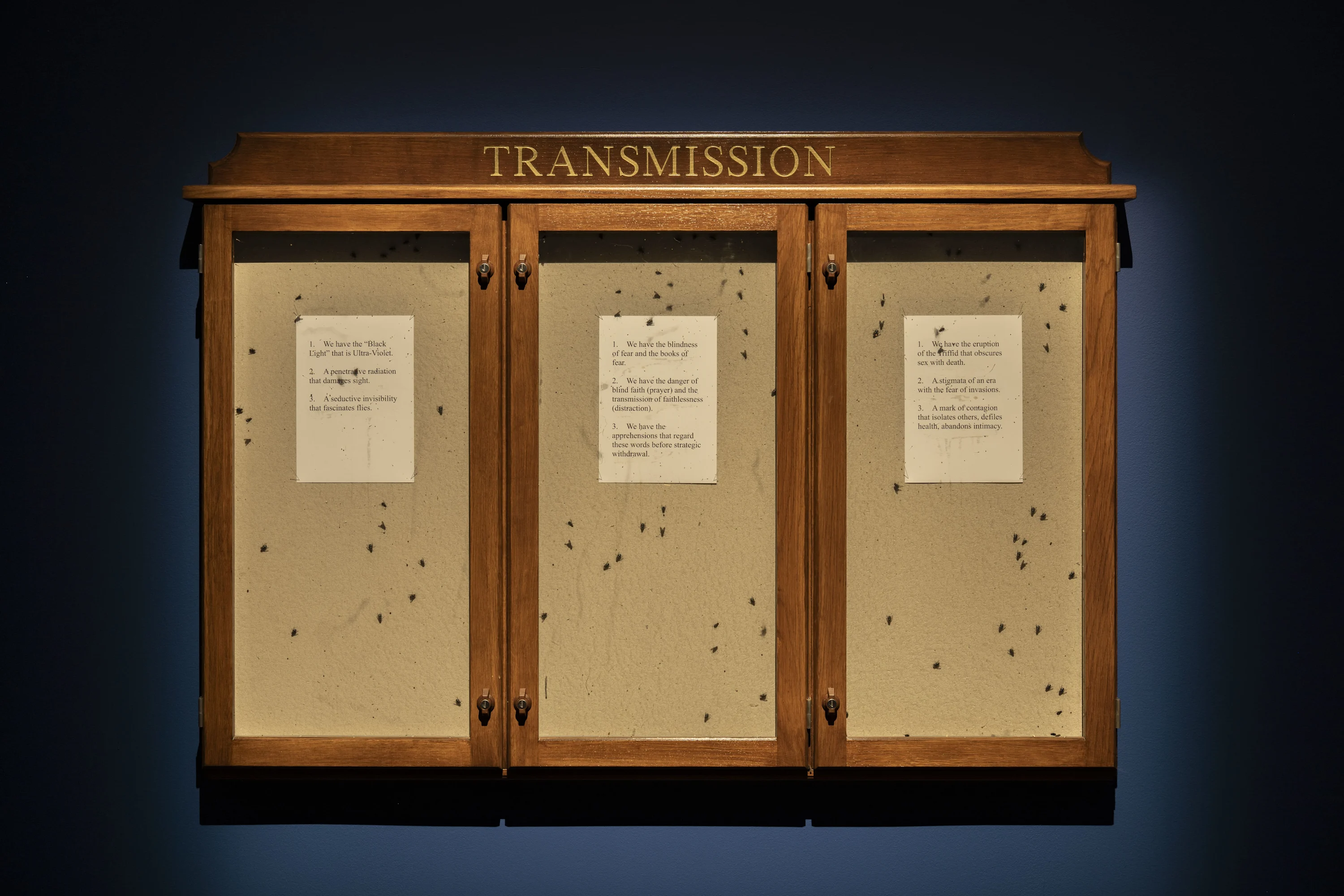

Trained at Saint Martin’s School of Art before completing his MA at Goldsmiths College in 1990, Hamad’s aesthetic was sharp and clean, almost laboratory-like, and often dealt with themes of transformation, danger, and control. His most famous works used glass containers filled with toxic substances like chlorine gas or hydrochloric acid, acting as metaphors for invisible threat, the body’s vulnerability, and the fragility of existence. The artist’s most famous installation “Transmission", shown at the Museum of Modern Art Oxford and later at the Tate in 1995, embodied this ethos: sterile glass flasks glowed ominously under neon light, balanced between seduction and menace. The work was a contemplation of contagion—both biological and societal—a reflection of his own experience living with HIV in a time when stigma often rendered those suffering invisible. Another element of the “Transmission” installation (which was originally created in 1990) included a glass case that showcased the life cycle of flies, and it’s this piece that has recently hit news headlines again: his peer at Goldsmiths was Damien Hirst whose alarmingly similar artwork “A Thousand Years” also utilised live flies, but debuted after Transmission. Make of that what you will…

For 30 years a huge back catalog of Hamad’s work was left untouched in their mother’s garage

And while it’s these examples of early bio-art that make up a large part of Hamad’s legacy, the artist was also a prolific painter, drawer and writer of short stories, and since his death, his brother Jamal has gone to great pains to champion his brother and preserve as much of the work that he made during his lifetime as he can. As Jamal recounts to Russell and Robert on this episode of Talk Art, that wasn’t always easy—for almost 30 years a huge back catalog of Hamad’s work was left largely untouched in their mother’s garage in North East London, and was only moved when the garage roof began to cave in. In a turn of either sheer luck or fateful intervention none of the work was damaged, even pieces containing hazardous chemical materials. Some of these pieces made up part of the exhibition at the Tate and are now at Whitechapel, but, for the first time ever, Jamal invited WePresent to photograph a number of never-before-seen paintings and drawings that have been in storage since his brother’s death, uncovering further depth to Hamad’s artistry.

My hope now is to make sure that Hamad’s work is looked after

“My hope now is to make sure that Hamad’s work is looked after”, Jamal says on this episode of Talk Art. “First of all, that the installations are looked after and supported, and known and talked about, and then [I want to] move onto the body of paintings that I have, and finally I think there is room to publish his writings and short stories. That is a stage for the future. A lot of people over the years have been inspired by [Hamad’s] work and that’s the fuel that has kept me going.”

Hamad’s legacy lingers in the way his work confronts systems of power—scientific, political, and institutional—without abandoning beauty. He alchemized fear into form, turning chemical hazard into conceptual contemplation. His practice remains a reminder that tenderness can exist within danger, and clarity within chaos, as much a metaphor for the times we find ourselves in now as when Hamad made them.

In a cultural moment still reckoning with identity and the politics of the body, Hamad Butt’s voice feels startlingly present. He didn’t just make objects; he made atmospheres—charged spaces where the viewer becomes part of a fragile system, invited to witness and to feel. His work continues to live on, inspiring a new cohort of artists and adding Hamad Butt’s name back into the list of British artists whose ideas ushered in a new era of thinking that came to define a generation. And now, thanks to the generosity of his brother Jamal, there is even more of Hamad’s work in the world.