Candomblé is an Afro-Brazilian religion that intertwines traditional West African beliefs with elements of Catholicism; it originated when enslaved African people in Brazil were forced to practice their faith in secret. Gustavo Nazareno’s statuesque figures—draped in flowing fabrics and rendered in jewel-toned oils—are orixás, deities that bridge the mortal and the divine, and he was drawn to paint them via ancestral guidance and a calling from a higher power. The São Paolo-based painter tells Maisie Skidmore how discovering the religion was both a spiritual and a creative awakening.

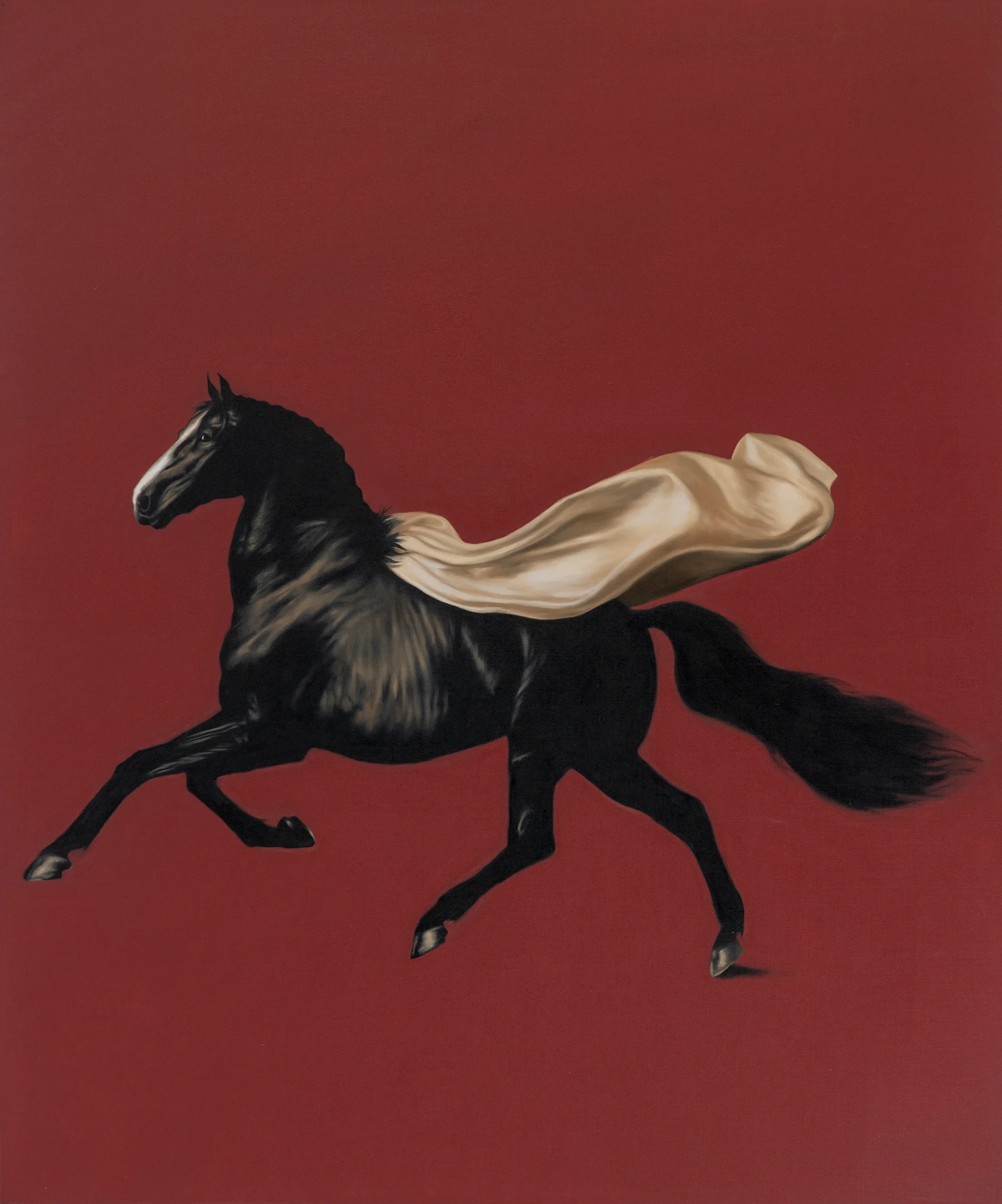

Gustavo Nazareno’s subjects are statuesque figures swathed in fabric; rich jewel tones of orange, vermilion and buttermilk yellow vivid against their Black skin. Otherworldly, but also oddly familiar—almost-gods, connecting the divine and the mortal realms. They are orixás, deities and ancestral spirits that originate from West African spirituality, and that play a central part in Candomblé, a rich and opulent Afro-Brazilian religion in which Yoruba elements intertwine with Catholic ones. If it weren’t for the orixás, this Brazilian artist might have never become an artist at all.

I thought, I am going to paint religious images, and people are going to kneel in front of them.

It’s a good story. Nazareno was born into humble beginnings in Três Pontas, Brazil, he tells me over the phone, in almost-perfect English with a melodic, lilting Brazilian accent. “I used to draw, really well, and even though [my family] didn’t have the tools to take me to museums, or travel, my grandmother was always trying to shape me as an artist.” In the absence of an academic entry to art, he stumbled upon a spiritual one. “My family was Catholic—not big Catholics, but they were devoted to the saints, and church. As a kid, I was obsessed with religious images. My art was guided by telling stories through faith.”

Nazareno set about teaching himself, with a discipline and an appetite for research that has since informed every corner of his work. As soon as he gained access to a computer at the age of 11 or so, he discovered fashion, and more specifically fashion photography. He began copying the covers of Vogue Italia, honing his skill by emulating the style of Steven Meisel and Irving Penn. He adored the work of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano for Dior, with their use of color and symbolism, and the elegant, flowing lines of couture on the body. In a bid to improve his English, he also watched drama-documentaries—one of which was a BBC production called “Raphael, A Mortal God.” It sparked a fascination with the Renaissance artist, and Nazareno began to teach himself about anatomy, too.

His hometown didn’t offer many routes out for an aspiring artist, however. At the end of 2017, Nazareno was in his early 20s, broke and deeply depressed. “I got a call from my aunt at Christmas, and she told me that she’d had a vision from her preta-velha,” he says. His aunt was a practitioner of Umbanda, one of many Afro-Brazilian religions. As Nazareno says, “A preta-velha is a spirit in Afro-Brazilian traditions who manifests the wisdom of elderly Black women who endured enslavement and historical violence. They are guides of patience, healing, humility, deep intuition and ancestral memory. Their speech is slow, caring and deliberate. They teach through affection and lived experience. They embody survival as knowledge.” His aunt’s vision had called for him to move to São Paulo, immediately. “She said, as fast as you can, pack your things and come here. You won’t come back.”

On his arrival in the city, Nazareno visited his aunt’s priest, who, having heard that he was a proficient painter (in fact, he had never picked up a paintbrush), commissioned him to paint the orixás, the Candomblé deities. “I felt like a young Raphael,” he says. “I thought, I am going to paint religious images, and people are going to kneel in front of them. This is what my life is going to be.” The experience inspired a deep devotion to the orixás. “It was so beyond what I could expect from beauty.”

It stands to follow then that Nazareno’s process is meticulous, worship woven into every step of it. His work draws on social, spiritual and cultural stories from South America and around the world, deliberately blurring the lines between fact and fiction, and his dedication to the narratives around his images is rich and thorough. Before beginning a painting, he will often write a story to set the scene, capturing characters in all of their eclecticism. He works with a series of wooden figures, draping fabric over them, and lighting them with candles to evoke the atmosphere he is looking for. This dramatic lighting underpins the chiaroscuro in his paintings, showing the fabric at its finest. “Most of the time the garment is holding all the story,” he says. “It's all about the opulence, because that is very much related to the practice in this religion. In a ceremony, clothing is something really special; you know the tradition based on the colors.”

Today, his studio in Vila Mariana doesn’t have any of the chaos characteristic of an artist’s studio. In fact, he chose the space because it reminds him of his grandmother’s house, simple and cozy. The books are alphabetized by artist name, the brushes neatly arranged. “I can’t stand paint stains. It’s very tidy, it’s very organized,” he explains. “When I receive studio visits, I’ll create a little mess to make it look like I’m working.” His fastidiousness goes hand–in-hand with his spirituality; his paintings are artworks, but they are also a religious offering. “This is my sacred space,” he says. “My theater. My church!”