Pakistani and Indian soap operas have been a part of Fatima Kaleem Khan’s life since she was a child, but she’s long been amused by the image they push of the “ideal woman.” In most series, “positive” female role models are shown aligning with these values, which often subtly mirror an underlying nationalist spectacle. Kaleem Khan tells Alexander Durie how she wants to show that “soft spaces” such as the home can be political, and how narrative framing in popular culture and propaganda shapes which forms of anger, discipline, and rebellion are celebrated or condemned.

For millions of people the world over, watching soap operas is an addictive pastime that transcends the label of “guilty pleasure.” Their heightened sense of melodrama brings a sense of entertainment––even escapism––to viewers, who debate over their favorite characters, and the often morally questionable things they do.

Soap operas from India and Pakistan have been a part of Pakistani visual artist Fatima Kaleem’s life since she was a child––coming for the “exquisitely dressed” female characters, but staying for the stories, which are “addictive in a weird way,” Kaleem says. “They’re slow, yet crazily dramatic… I’m watching three at the same time right now, even when I'm in the studio, just in the background.”

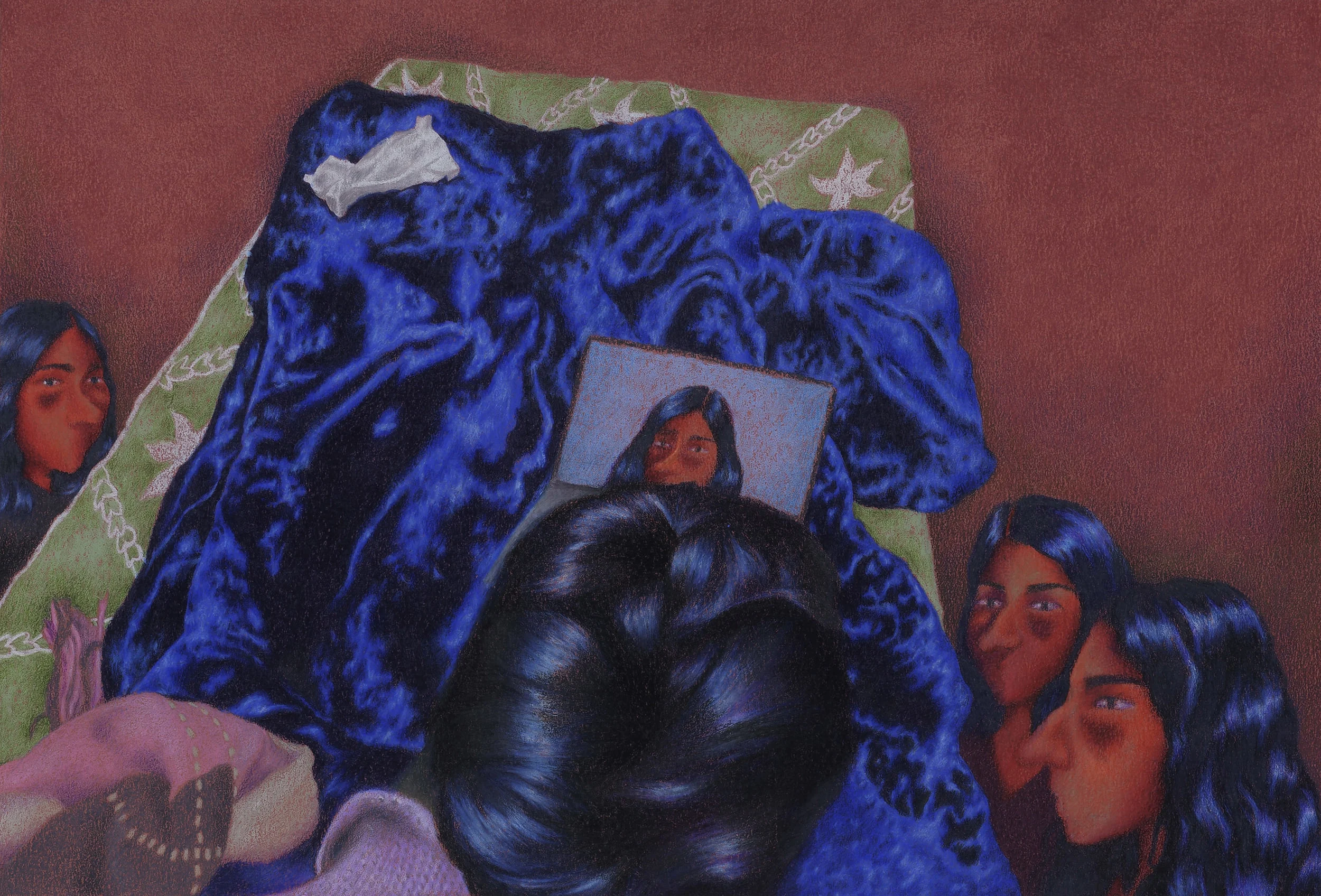

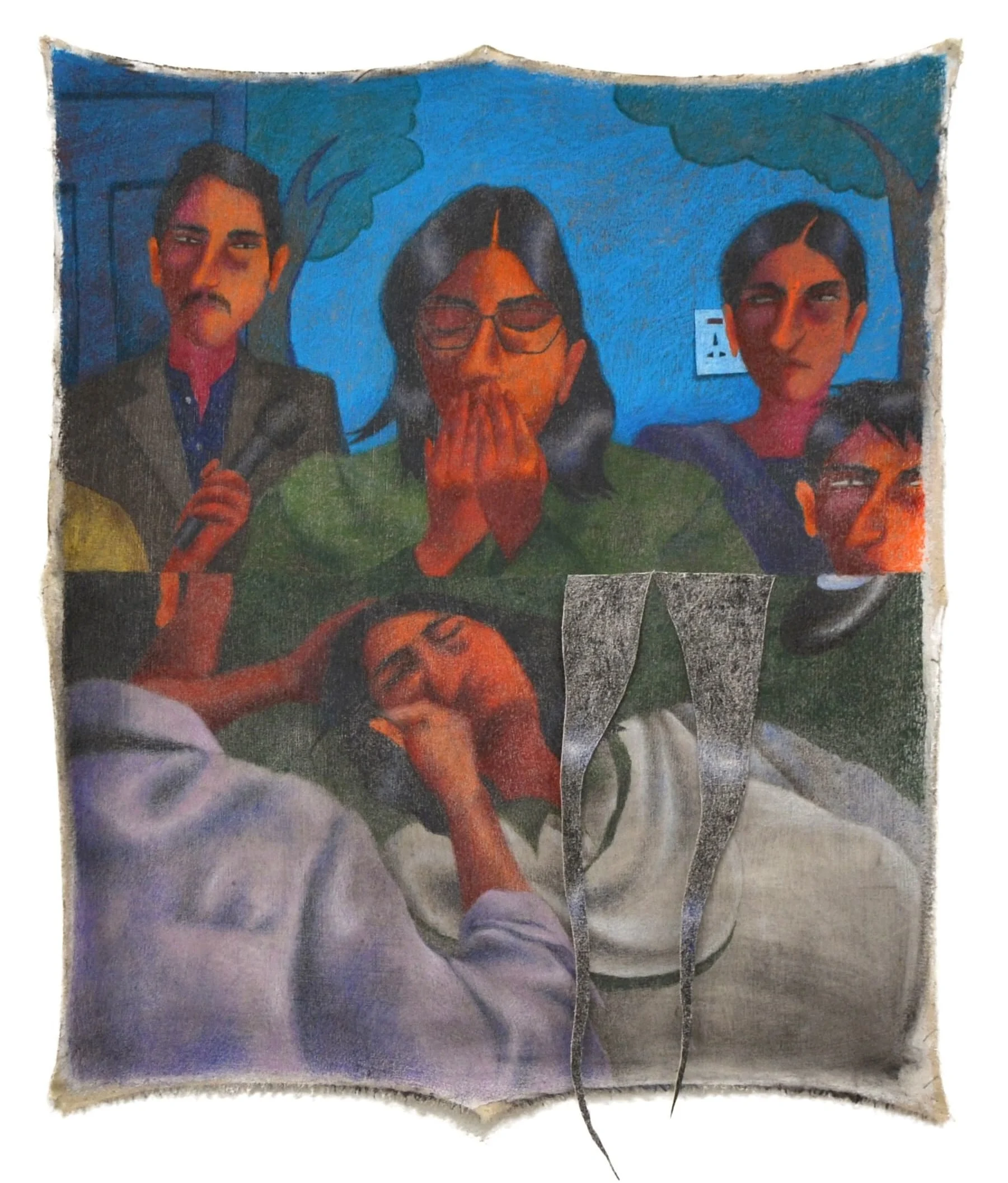

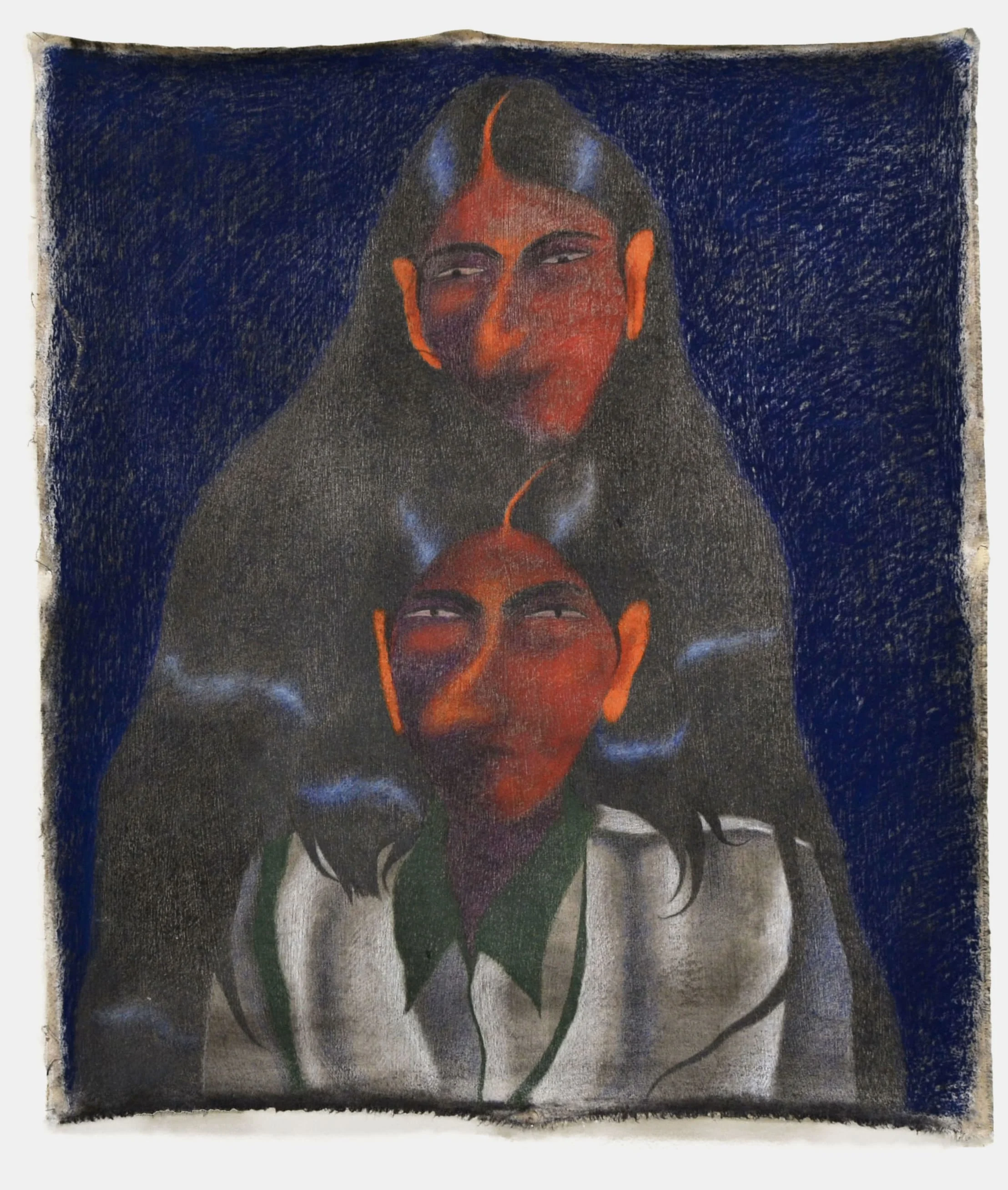

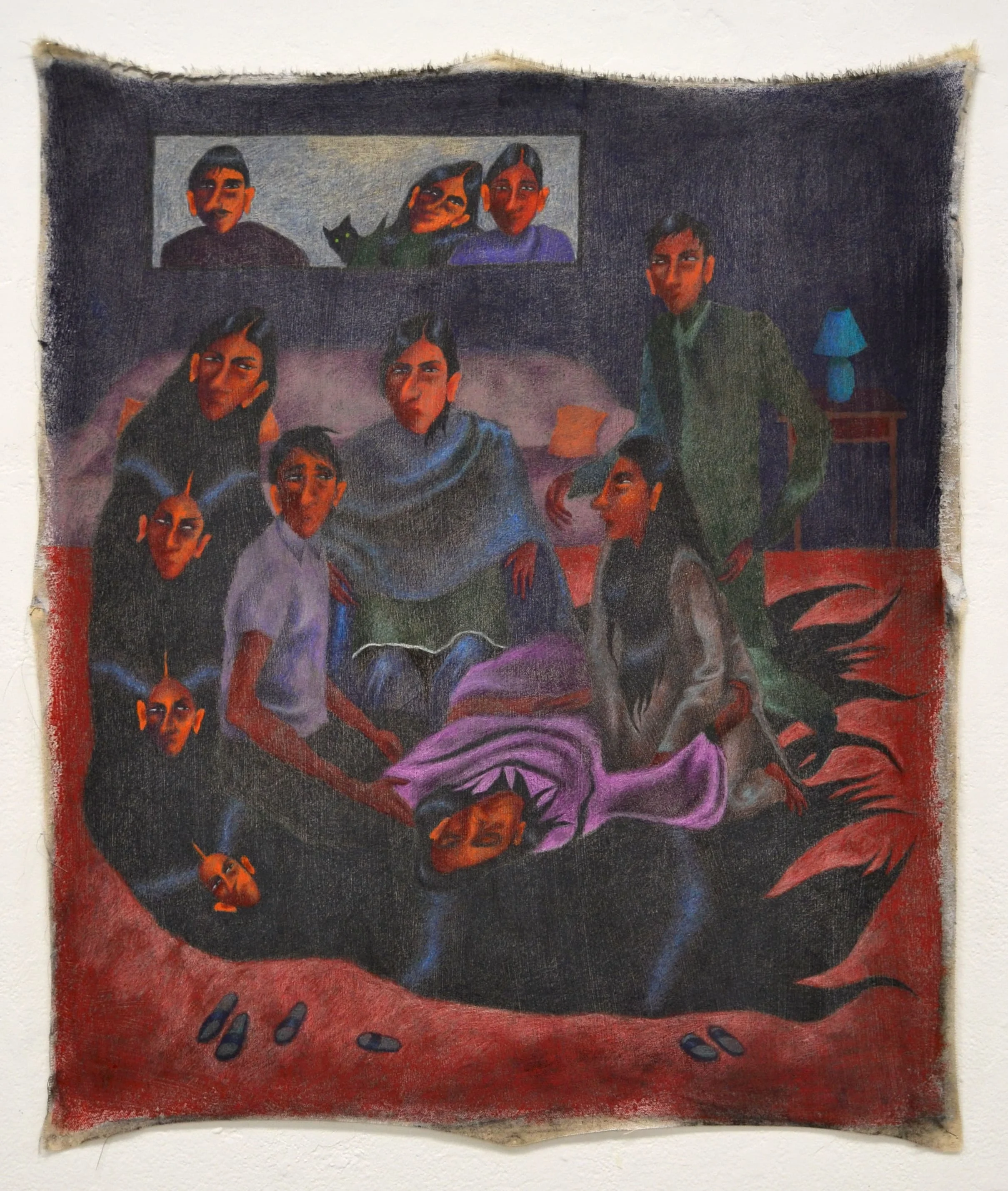

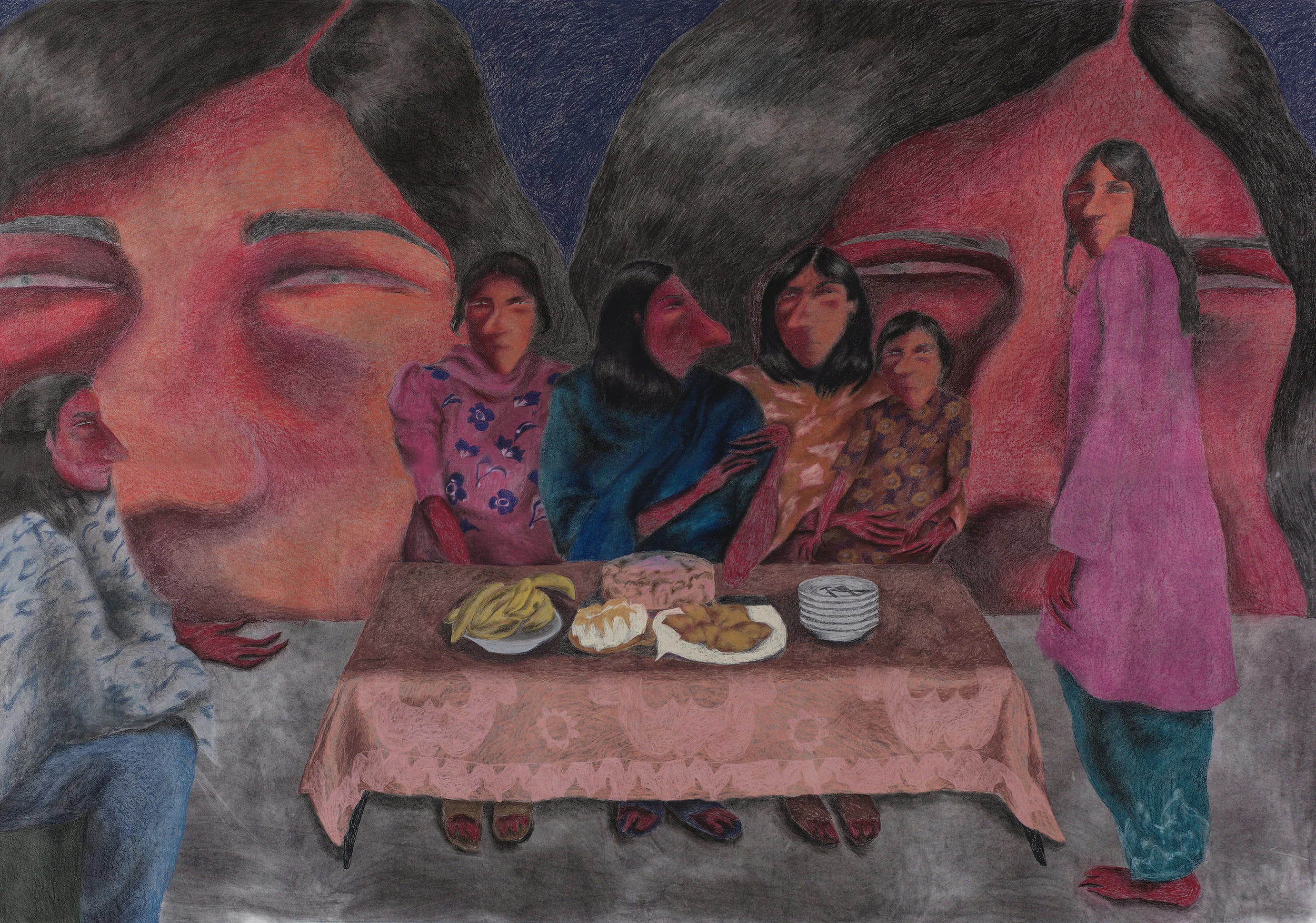

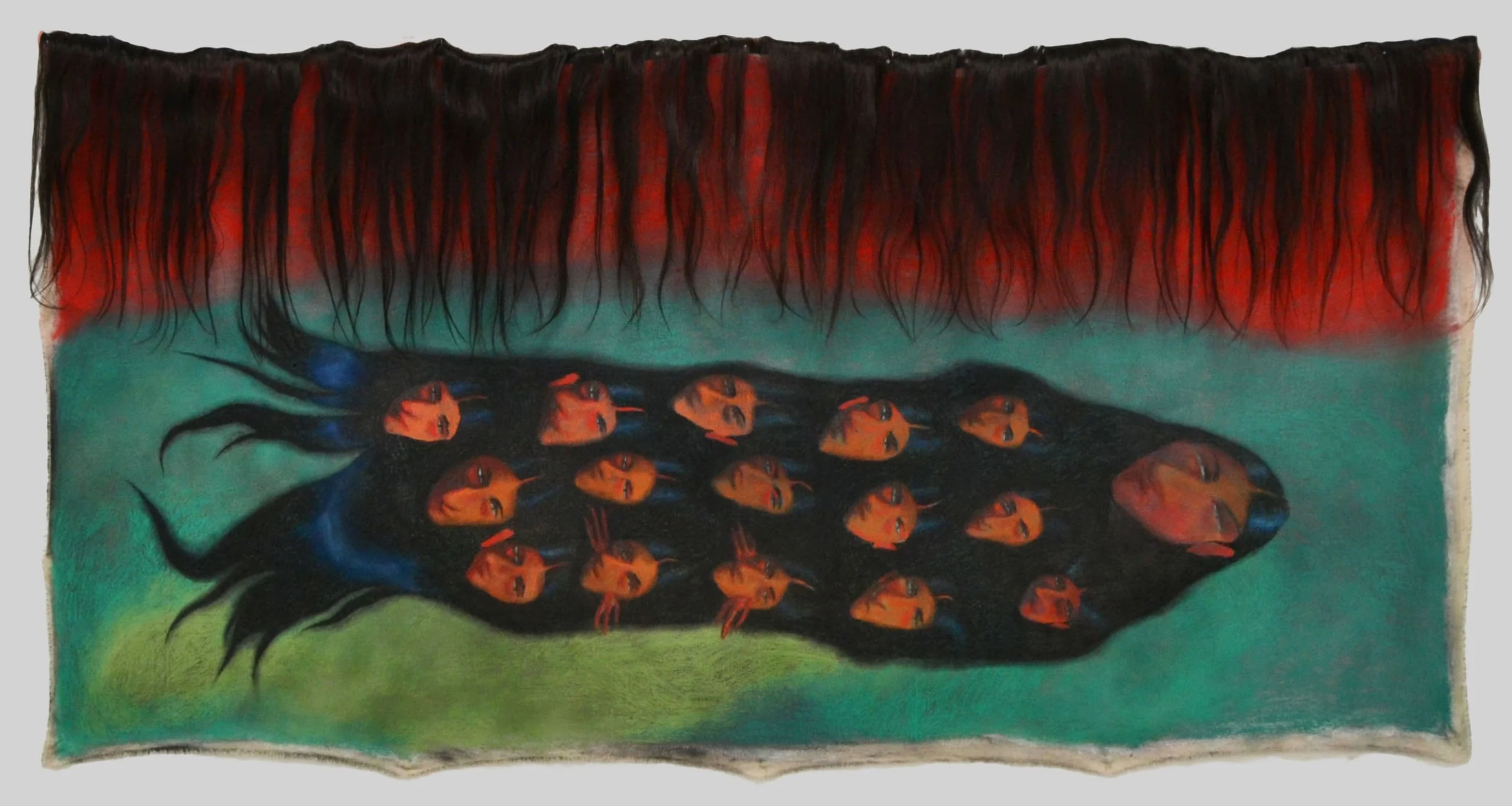

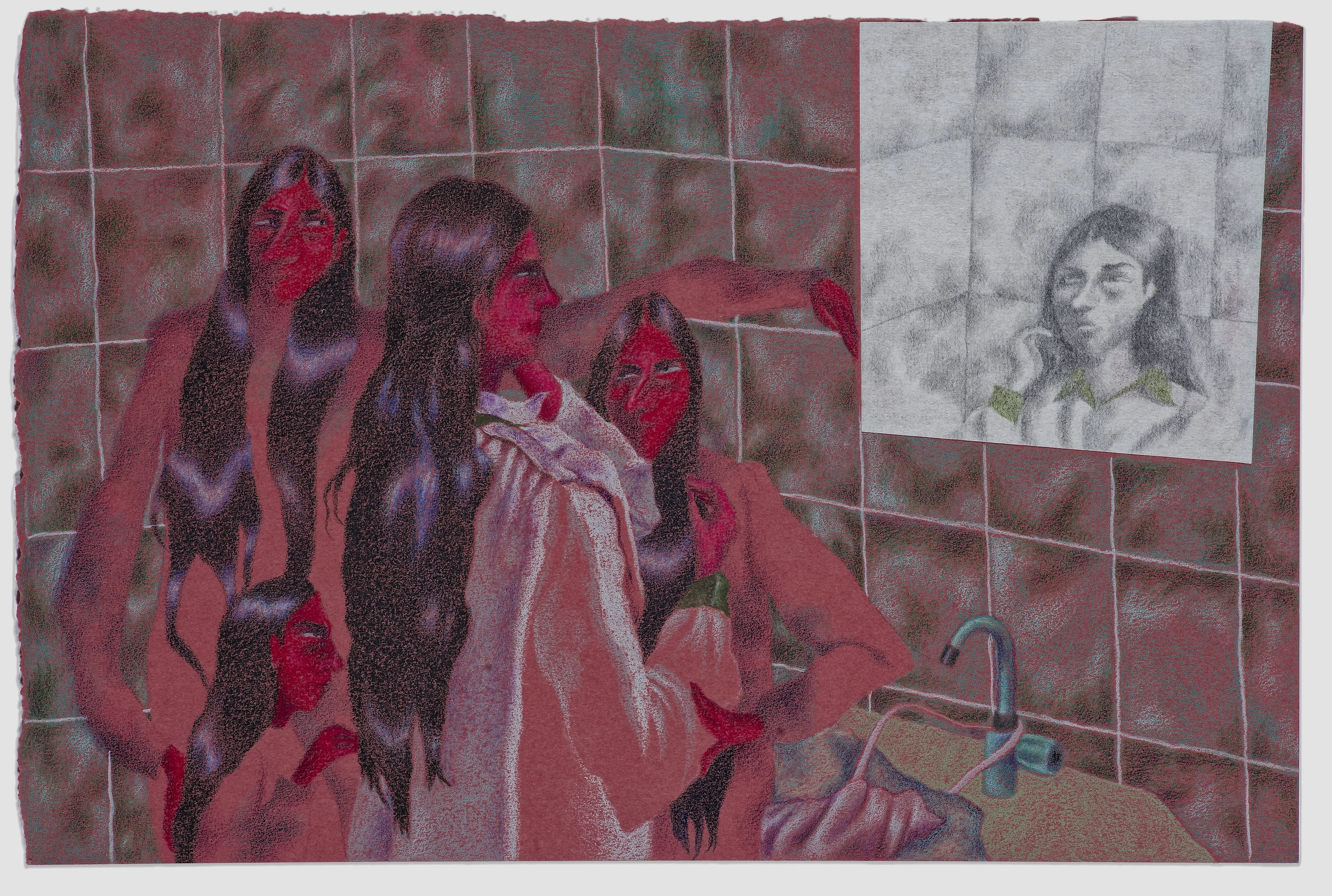

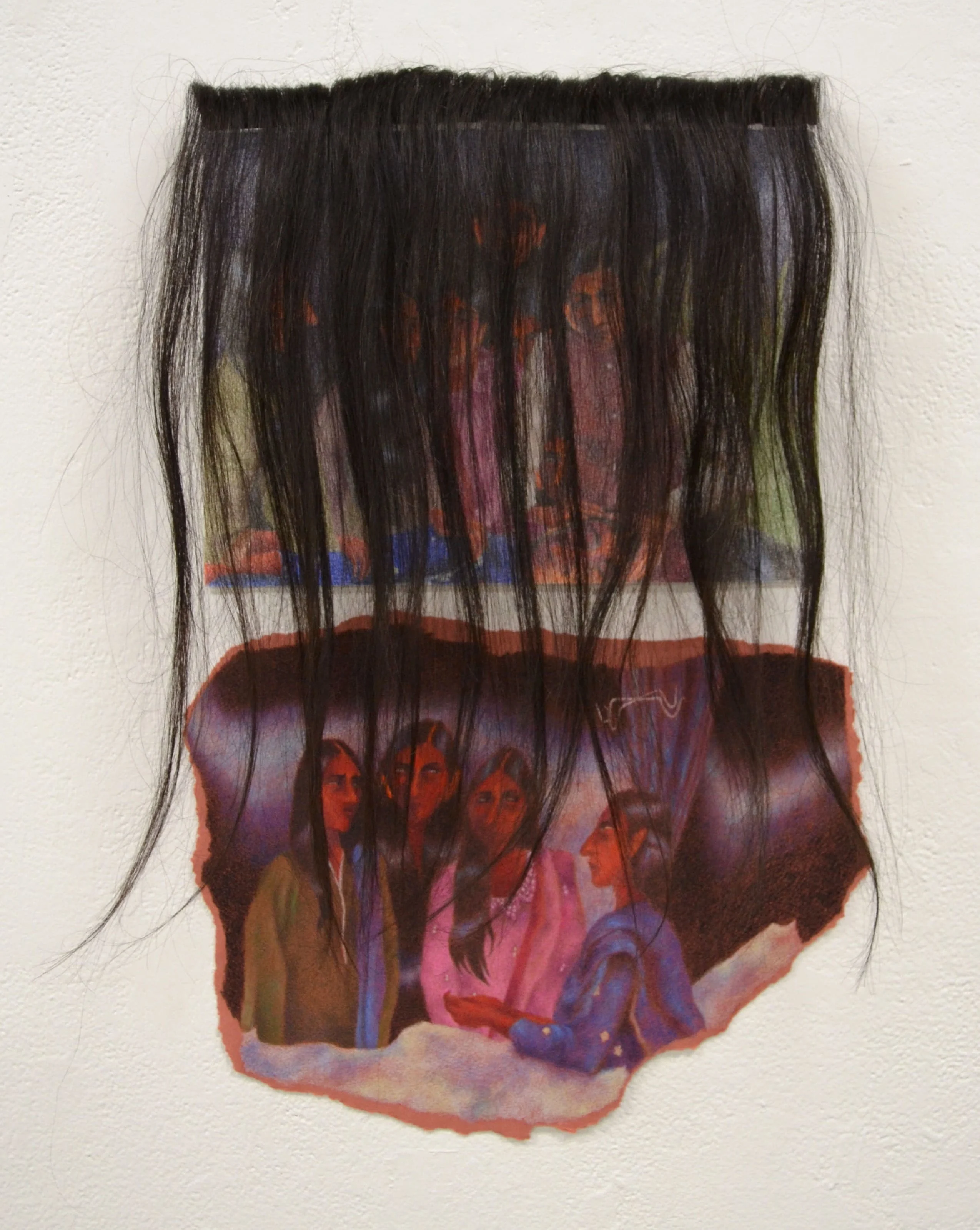

Kaleem, who is now based in the US and pursuing an MFA at Virginia Commonwealth University, says that soap operas are generally looked down upon by many people in Pakistan, particularly older men, who view them as lowbrow. Yet in her new series of drawings already exhibited in Toronto, Mumbai, Islamabad and soon in Paris, Kaleem defies these preconceptions, and offers critical and whimsical reinterpretations of South Asian soap operas, in drawings that are colorful yet melancholic, vivacious yet frightening. The soap operas are just a starting point for her to deconstruct societal issues; in these illustrations, the personal intersects with the political, exploring themes of domestic life, nation-building, spirituality and female disobedience.

I was very interested in what role the feminine and the domestic play in upholding those values enforced by the state.

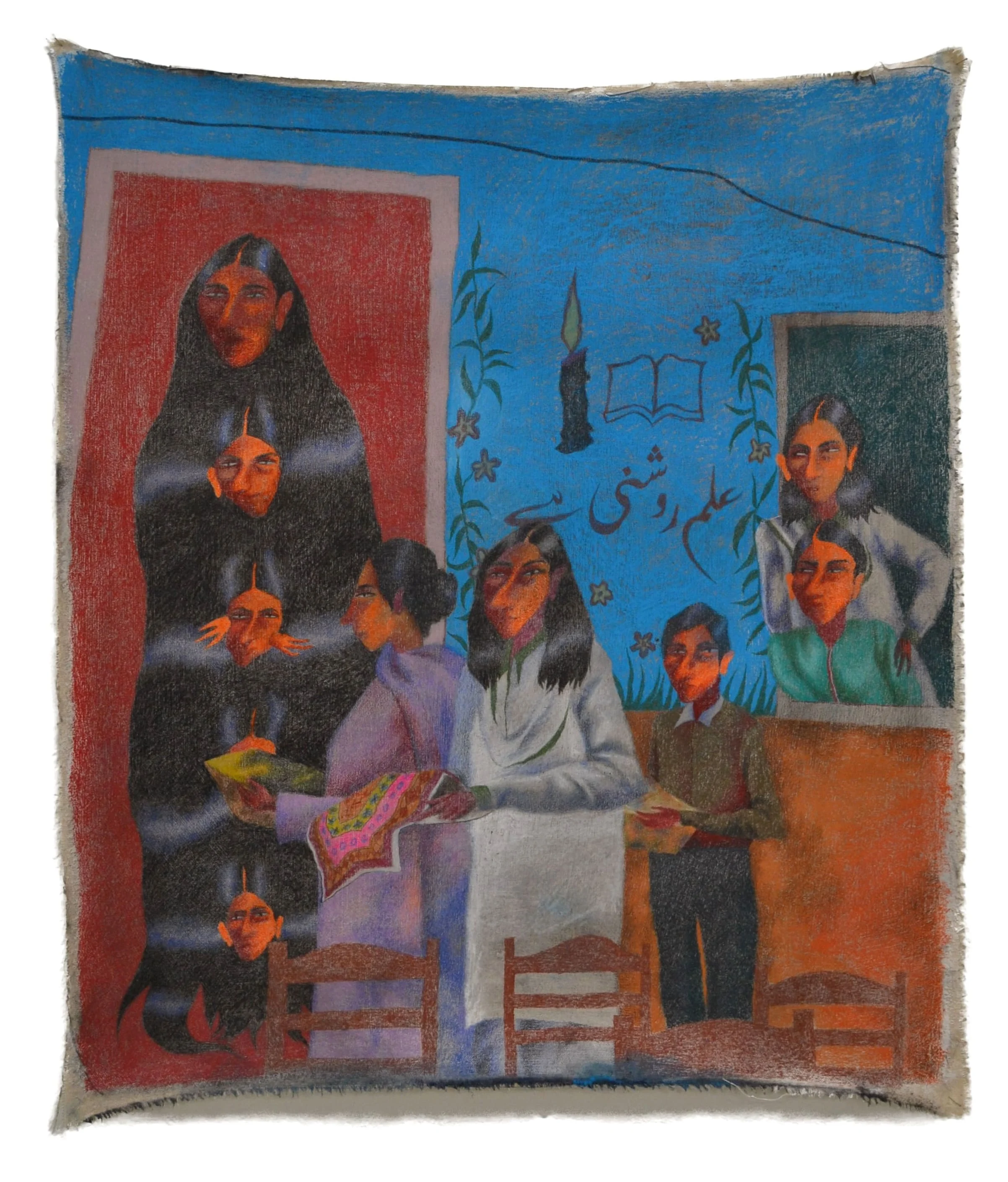

“A lot of my recent works are drawn from soap opera stills, and I see this confluence of the idea of discipline in the home and in the school,” Kaleem tells me. Her interest in these shows and issues came from a personal connection, as she states that she is interested in a lot of soap operas that are centered around college girls and how much responsibility for their upbringing falls onto their mothers.”

This brought back memories of her own upbringing, both domestically and educationally. She recalls singing the national anthem during school morning assemblies in the blistering heat, the way students' uniforms would be soaked in sweat before the school day had even started and how students would faint regularly. “I draw parallels between the drama of students fainting and the melodrama of soap operas—betrayal, spying, confession and revenge, are tropes I'm particularly interested in.”

Kaleem and her family moved around Pakistan a lot when she was younger due to her father’s work, and she changed schools more than a dozen times. She experienced very different curricula, from O-Levels by Cambridge University to army schools “where texts would often reference heroicism of martyrdom and attempt to kindle a patriotic spirit in students, Kaleem says. These contrasting systems made her “especially interested in how history was told in those different books.” In these schools, and at home, Kaleem felt a strong sense of discipline that imposed definitions of what the “ideal woman or girl” should be, which led to her fascination with soap operas and how they uphold similar ideas.

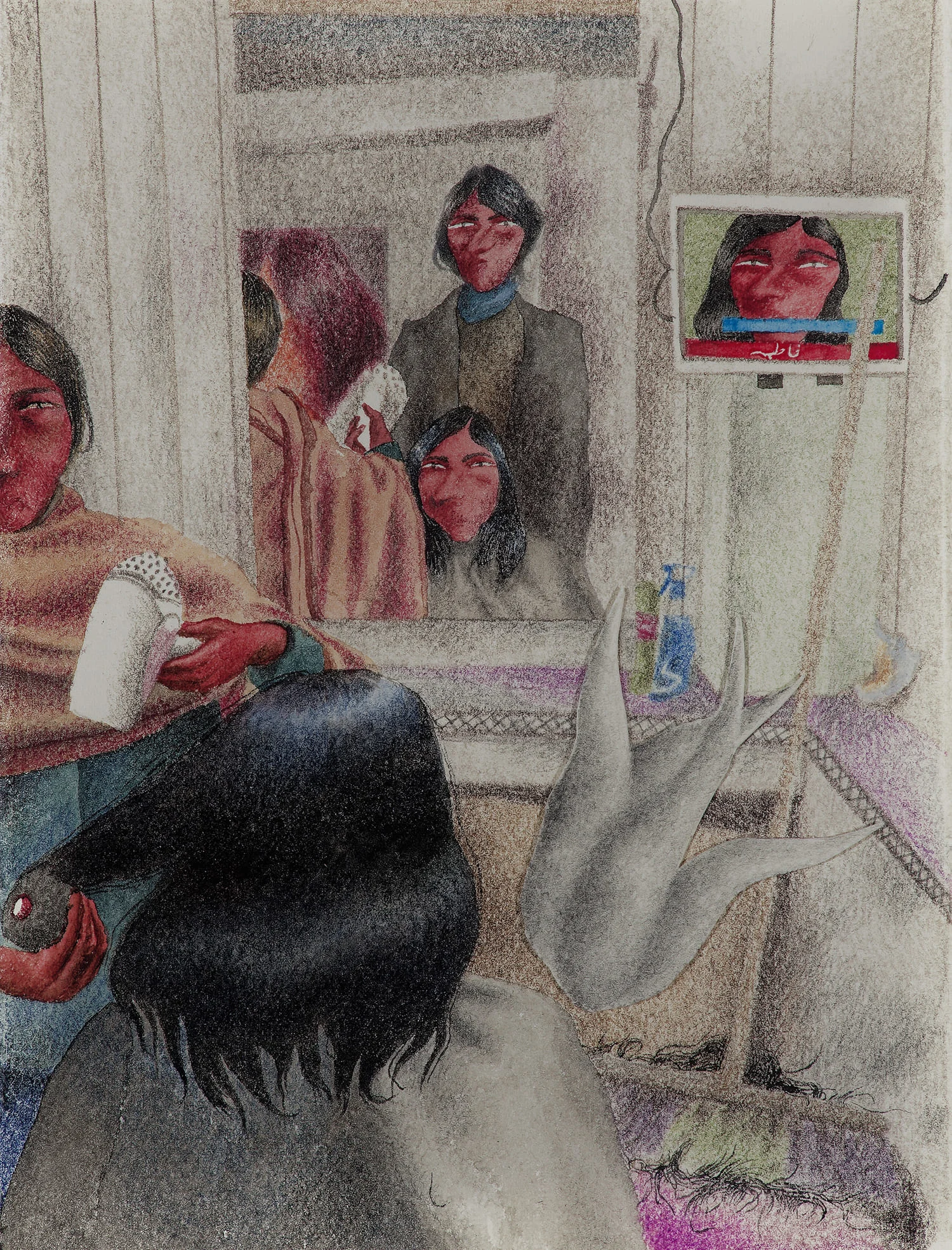

“One of the reasons why I got really into soap operas was because the ISPR [the media and public relations wing of Pakistan’s Armed Forces] got interested in promoting certain things,” Kaleem says, “they sponsored two TV serials when I was just out of high school, and I was particularly intrigued by Sinf-e-Aahan where five women are shown breaking glass ceilings by joining the military.”

She mentions how productions such as “Sinf-e-Aahan” and “Ehd-e-Wafa” developed binary roles between “the antagonist” and the “ideal woman,” where the latter typically holds a patriotic one. The ideal woman is shown to have a role in nation-building in this way, while “the antagonist is shown as the opposite of that. She is countering that authority.”

Drawing ideas around domestic and school life drawn from South Asian soap operas was a way for Kaleem to show the soft power those spaces can hold in terms of nation-building. “My work explores how feminine spaces, particularly the home and school, contribute to the shaping of domestic and nationalist narratives,” she says. “I was very interested in what role the feminine and the domestic play in upholding those values enforced by the state.”

Kaleem feels that female antagonists are portrayed as evil and manipulative in state-funded soap operas through their rage and at times through their association with malevolent spirits and magic, but for her these characters are interesting. “I’m really interested in the antagonist, and in the way that she embellishes stories, the way she creates a whole alternative understanding of whatever is happening,” Kaleem says. “I’m thinking of her power to rework the narrative framing in her story as an opposition to the propaganda and structures that empower the state.”