Chad Mclean’s year-long obsession with Black horse riding culture in the American South was instigated by a single video: a family galloping through woodland. For his WePresent-commissioned project “Black Horse Power,” he spent a month across Houston, Dallas and South Carolina immersing himself in the communities of riders bringing the rich tradition of the culture into the present day. He tells Natty Kasambala how these historically displaced communities are preserving the stories and memories of the ancestors who came before them.

“The funny thing is no one actually got back to me before I got there,” laughs photographer Chad Mclean. After a full year of digitally immersing himself in the world of trail rides, horses and cowboys, he had finally landed in the American South, alone. The plan was to spend the next month diving deep into the culture that had captured his fascination virtually, for his personal project “Black Horse Power.” “I went alone because I thought, let me go there and fully be a person… I even went the long way round with [release] forms because I didn’t want to scare anyone,” he says, instead opting to swap socials and nurture the connections he made over time. “I’ve already got [this] British accent, I already come across as proper and I’m out in the country…I can’t tell you how many people asked me, why are you here? What’s going on? You came from London, for this?” Mclean recalls.

But it didn’t take long for his network to expand and his leap of faith to start paying off. The first thing he did was get himself straight to a “cowboy shop” to stock up on the essentials needed to navigate these new pastures. In there, he serendipitously got talking to a young woman buying her first boots and it turned out they were headed to the same event that Saturday. Arriving four hours early, his equine adventure began.

I saw this Black family… galloping horses through woodland. And I thought, what a beautiful thing.

Growing up, Mclean thought he had a pretty decent grasp of Black American culture. British-born and raised in Northampton, with Jamaican and St Kitts and Nevis heritage, he’d visited the States at least once a year in his childhood to spend time with family around the East Coast: from New York to Boston, New Jersey to Connecticut. It wasn’t until he found himself confronted with a completely alternate reality while scrolling on TikTok that it dawned on him, he’d barely scratched the surface. “I saw this Black family riding horses through woodland, like galloping horses through woodland. And I thought, what a beautiful thing,” he marvels. “It’s so far away from anything I know.”

With a background first working at Nike before kickstarting his own freelance photography career shooting BTS footage for his artist friends, Chad credits his Caribbean upbringing as the source of his endless cultural curiosity. “Even with both [my parents] being Black Caribbean, there’d be some things that they just say differently. Could be as small as a fried dumpling in Jamaica is a Johnny cake in St Kitts,” Mclean explains. “Even those little differences really highlighted to me the differences in Black culture from early.”

That fascination led him straight down the rabbit hole two years ago, where he went on to discover the nuances between a Houston or Dallas city backdrop and the countryside of South Carolina, the different music being played at rider gatherings, the hierarchical structures of their crew and coalitions and even the different dress codes: “It was the mirror image of me growing up and having the dumplings versus having the Johnny cake. That, ‘ah, we’re the same but we’re different.’ And it’s still beautiful, it’s still made with the same love and it still tastes the same.”

He’s full of tales from his time in the US and knowledge of their customs and history, “I believe that we should learn, and the best way to learn is by experience… Let me go and deep dive into a specific part of culture that isn’t mine but I can feel close to.”

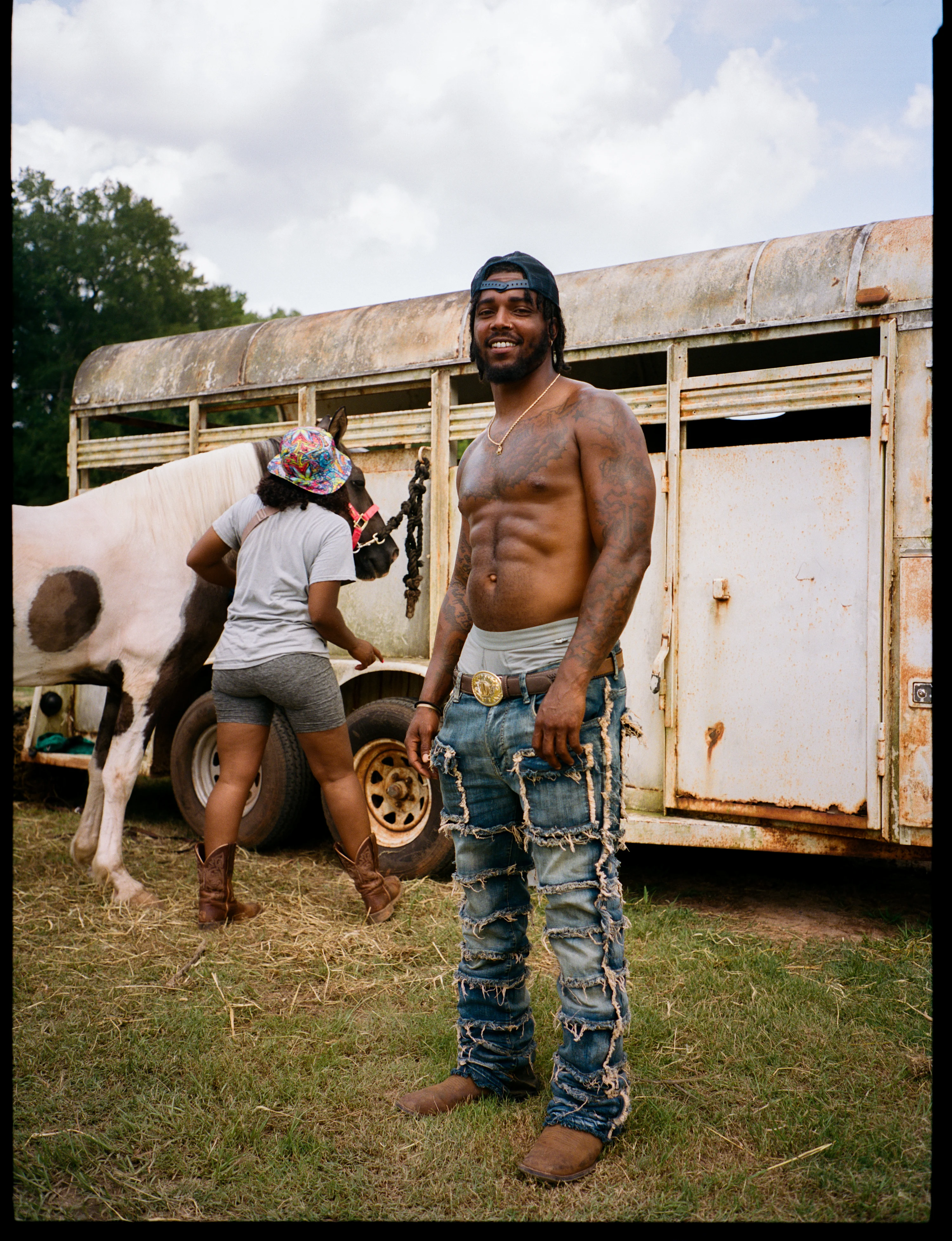

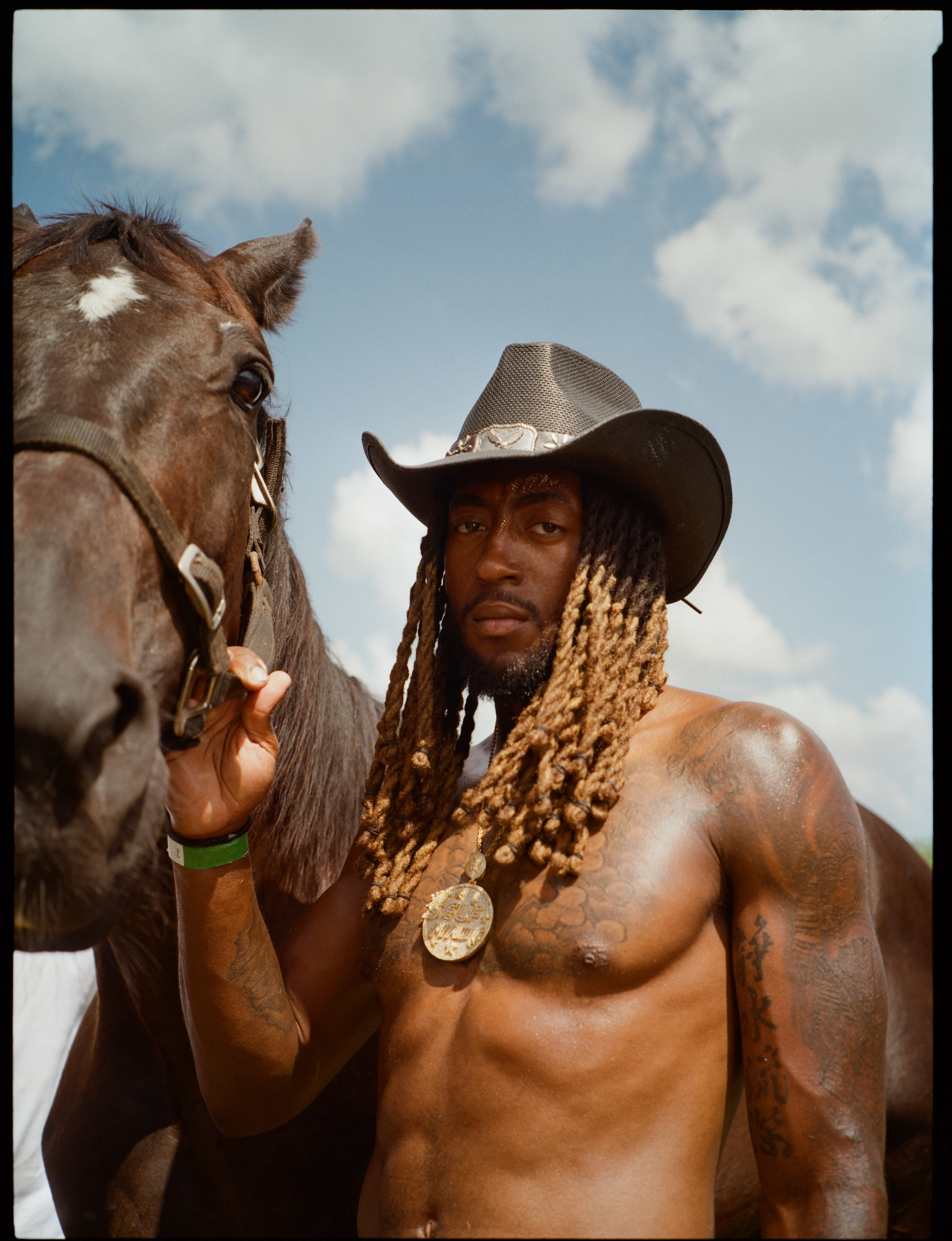

The world he found at the end of his search teeters at the edge of modernity and tradition, years of history rejuvenated and propelled into the present. The images captured are vibrant with life and contemporary textures: a shirtless man courts a giggling woman on horseback with iPhone in hand, a cowboy poses iced out in chains and grills, children mount ATVs and gilded saddles in dungarees of every shade. The blue skies and verdant landscapes set off the rich browns and golds and brightly assorted crew colors.

There’s an ease with which every rider appears, perched atop these equally statuesque creatures; the horses embody a rare kind of stillness, seeming almost like an extension of their companions. The frames feel soft and hard all at once—entirely natural, yet quietly monumental.

Do you know how powerful it is when someone sits on a horse?... We are that. Black people are on the horses, we have that power.

Often majoring in sports photography within his commercial portfolio for the likes of JD, Nike, Wimbledon or Sports Direct, Mclean is no stranger to a fast-moving subject: “I like doing, I like movement, and things of power and grace,” he says. But he intentionally chose not to employ his usual toolkit for this project, eschewing the usual slow shutter speeds and tightcrop edits in favor of a complete, naturalistic approach. “I wanted the world to be seen as it would be through eyes,” he says. “There’s no technical bias to it. I was just working with natural light, just me and my camera. Everything is as is.”

For Mclean, this project emerged from a place of joy and celebration, “I’m into cars and we have brake horsepower. I was like cool, but do you know how powerful it is when someone sits on a horse?,” Mclean laughs. “You go around London and you see these statues of people on horses, they’re people of presence. We are that. Black people are on the horses, we have that power.”

In the end, despite its uncertain start, the trip went almost exactly as planned. Mclean encountered the true embodiment of Southern hospitality, witnessed the visceral art of rodeo and made lifelong connections. But it was also full of unforeseen revelations: “The personal learnings were more from a connection point of view, of just how close you are to history,” he says. Speaking to a young woman at a South Carolina trail ride, he learnt that as far back as her ancestry goes, each generation since emancipation has lived in the same house, on the same acreage, that she lives in today. “And they rode horses,” he adds.

Black Horse Power is [about] understanding that they started it. It’s not undiscovered because people do know about it, but it’s underappreciated.

Mclean likens that image to the infamous juke joint scene in Ryan Coogler’s “Sinners.” In it, a musical number soars to the point that it transcends time and space. All of a sudden, in the same room, at the same time, entire generations of history sit alongside each other, the camera roving around as the sounds and crowds overlap and weave. It spoke to how those who have been historically displaced find renewed ways to create and preserve their culture in communion with those that came before them. “[For them] to still be recreating the same movements, in the same environment, maybe having similar thoughts,” he says. It gave him a new perspective on the value of lineage and ritual, especially in resistance to systemic erasure and oppression, as well as a brand new set of questions like, “how close are we to our ancestors?

“I kind of went on a retrospective journey of, I don’t know what my ancestors did. I know as far as my grandad… We’re so close but we’re so far. And that’s also where [their] power comes from.” In some ways, Mclean’s appetite for exploration is a manifestation of that too, with the wider scope of the entire Black diaspora—investigating how we might both empower and be empowered by our similarities as well as our differences. And for its wider audience, it’s a practice in recognition. “Black Horse Power is [about] understanding that they started it,” Mclean says. “It’s not undiscovered because people do know about it, but it’s underappreciated.”