There’s a lot of pressure on artists to stick to a defined style these days, but British creative Cato.ink pays no mind to that, with a constantly evolving MO that spans collage, painting and airbrushing. He tells writer Yaya Clarke how he uses his multimedia practice to explore the foundations of art, belonging, and Black culture.

As an audience, we have long taken pride in our ability to recognize and grapple with the work of an artist through their “style.” Be it a rapper’s flow, a photographer’s epochal subject matter, or a painter’s palette, it’s something we search for and how we define the art of past and present. But for south east London-based artist Cato.ink, style is merely a tool of expression and a way to “make sense of my scattered interests and Blackness,” he tells me over the phone. Being careful not to get caught up in the “adrenaline rush of likes online,” and even his own perception of the work he’s currently creating, he shows us a practice spanning painting, collage and airbrush techniques, creating a window into himself and his surrounding world.

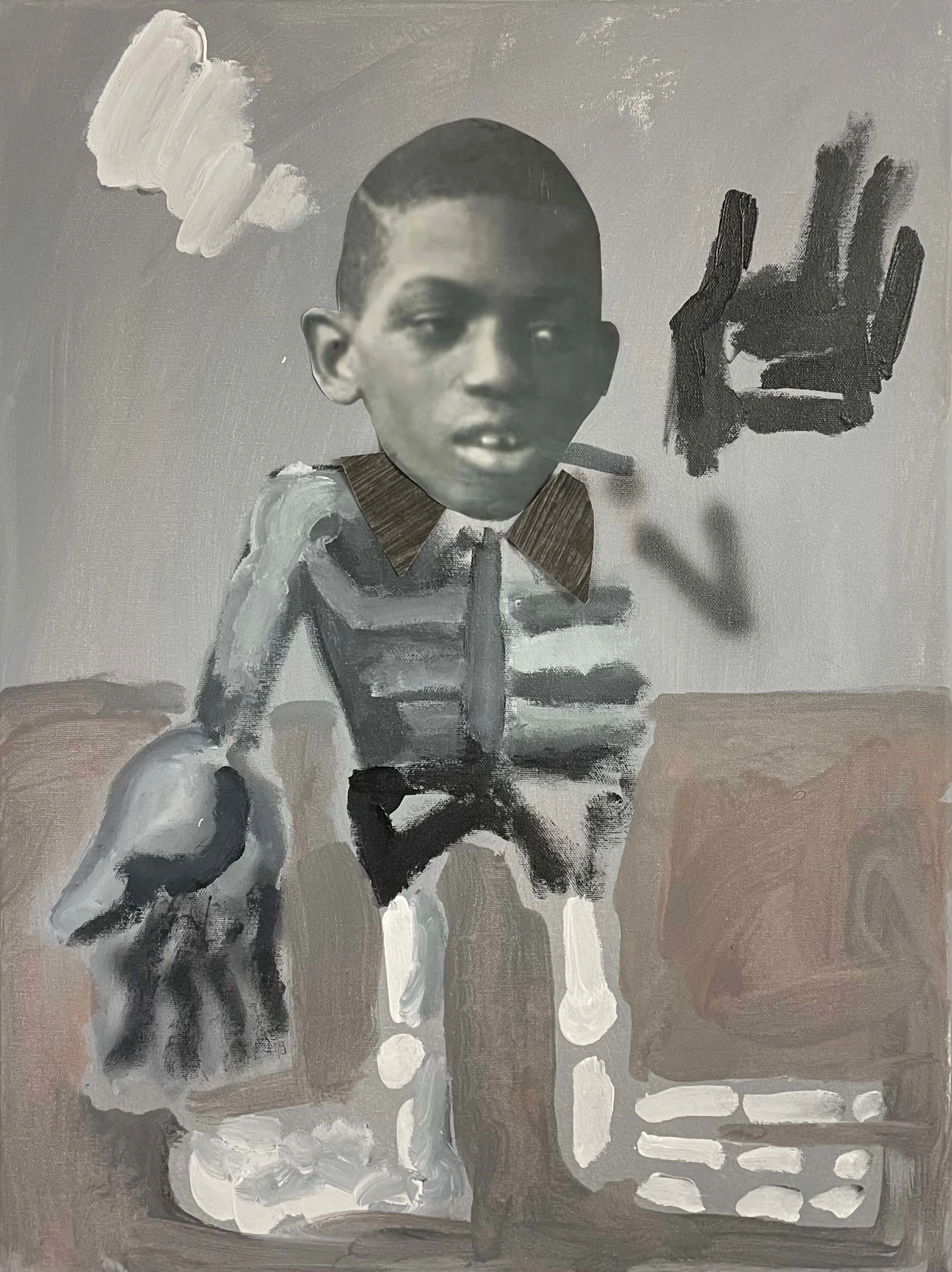

Growing up in Brighton, with a creative family and friends, his penchant for pairing Black archival imagery with both mundane and bustling scenes makes him as much a child of New York, Kingston and London. “I’m drawn to any place with a Caribbean block, street or community,” he says. “My grandparents came from Jamaica, so it’s the culture I’m drawn to.” In the sketches for his acrylic and collage piece “The Pugilists,” he uses the face of a boy from the photograph “Subway Two Boys” by Danny Lyon (1966).

When I asked why he incorporated the face of an unnamed boy in preparation for a piece that references Muhammad Ali and George Foreman’s “Rumble in the Jungle” fight of 1974, he says, “my dad showed me the fight when I was younger, and he was a boxer as a kid. It was a way of connecting to the emotions I felt afterwards and how it may feel for a young innocent boy witnessing that element of violence,” making it clear that his pieces are as much a personal resolve as they are historical.

The blackness of his acrylic airbrush figures—made by “painting black and spraying white on top”—are no more of a style than they are a critique. “I’m always in conflict with the illusions of race we’ve been given or a so-called ‘Black experience’, and being mixed-race has amplified that for me. But I do revel in the beauty of the culture, I always yearn for it,” he confesses, making his inspirations of Kerry James Marshall and Romare Bearden no surprise. And much like Marshall, the blackness of his characters are a must, turned mastered technique, giving the viewer a foundation on which to view scenes of Black life.

In the piece “The Barbershop,” there are two painted figures, the barber and client, shown holding a silence, and the client reading “The Black Panther” (the group’s eponymous publication that ran from 1967-1980). “I never went to the barbershop when I was younger and it feels like I missed out,” he tells me, another example of the artist finding himself in fragments of history.

Recently making his foray into self portraiture through oil paintings boasting color and “inspiration from Botero,” Cato admits. “I wanted to try something new and stretch my palette. My other work almost has a metallic level of blackness to it, a fantasy. I’ve always wanted that but at this moment in time I don’t think I can create paintings of myself as dark as my other figures.” Sharing that his mixed-race heritage may be the reason for this, he continues, “That’s why I see sticking to one style as stifling because you may miss out on a form of expression.”

Speaking of collage like “toys that you can move around until you find a place for them,” Cato sees the medium as the most freeing way for artists to learn more about composition, color, shadow and form. Reflecting on the foundational aspects of his collage piece “The Block,” he says, “I can see Picasso's style of eyes, Basquiat’s chalk and the street view that I’ve always been so fond of.” And with hopes to develop everything into moving image in the future, he speaks adamantly: “You have to try everything, don’t get caught up in style. Steal from your favourite pieces and eventually you’ll become your own invention.”