In a new book, “Rain On Dry Earth,” photographer Benjamin Rasmussen spotlights the Petrichor Foundation, a grassroots women’s football movement in Cameroon, and the girls fighting to change what their future looks like, on and off the pitch. Rasmussen tells Sam Diss how a team of local collaborators and contributors came together to tell this important story, and to capture the girls as the strong, powerful athletes they are.

It starts like this: A few kids in scuffed sneakers, sprinting full pelt after a ball under a setting sun in Yaoundé, Cameroon’s capital city. They’re playing for each other, for the coaches who believe in them, for the fathers who didn’t get their own shot, for the mothers who didn’t think this was possible, for the brothers who drove them to training, sick of the arguing at home. The ball skims off the dirt. This is the country’s dry season—hot, heavy, still. But the young women and girls of AS Petrichor play on, waiting for rain.

Photographer Benjamin Rasmussen had spent years photographing athletes. The polished, high-performance, glossy kind. But this was different. “These weren’t professionals. They weren’t celebrities,” he tells me. “But they were doing something I hadn’t seen before. They were using football as a way to widen the world around them.”

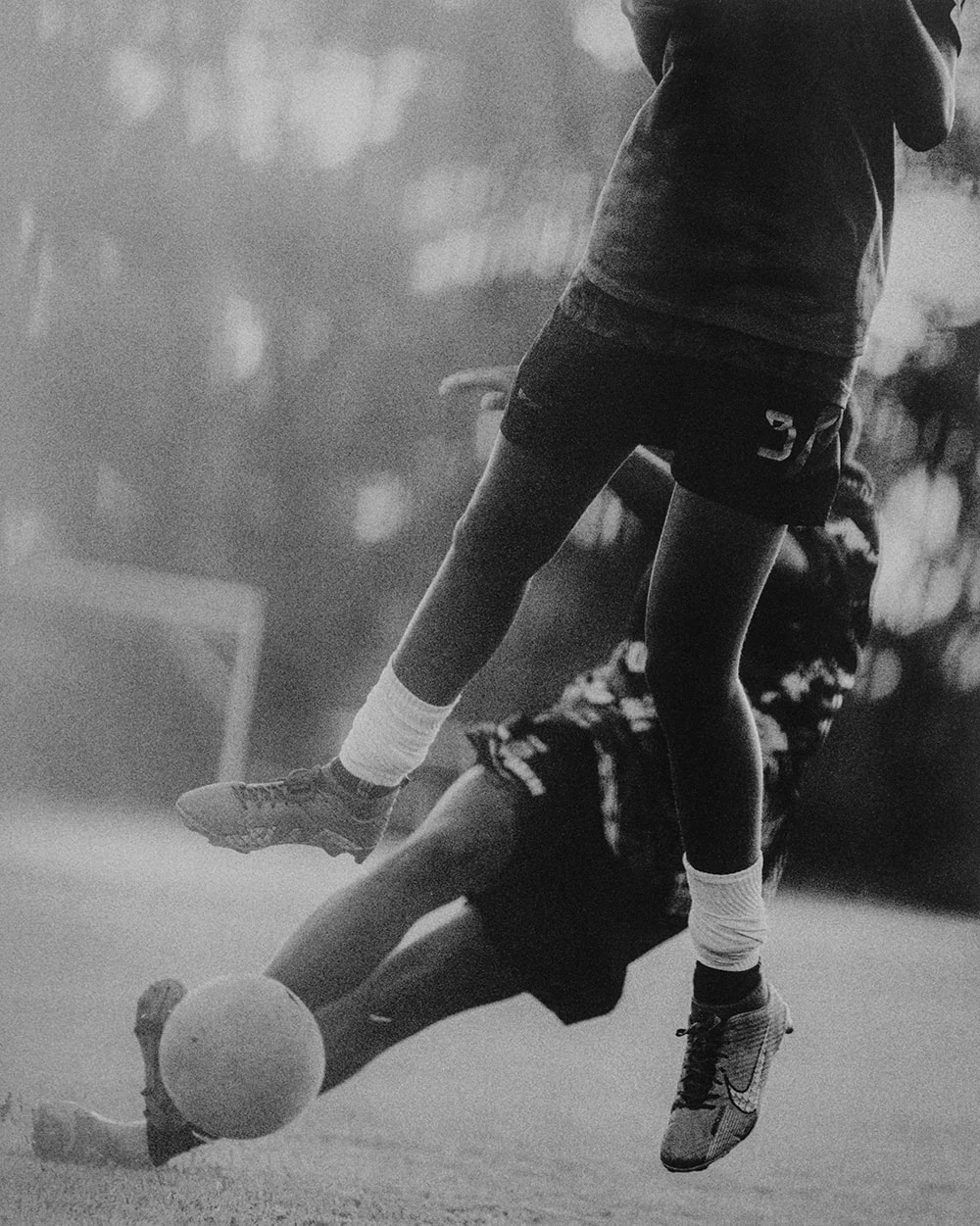

Rasmussen travelled to Cameroon to document the work of the Petrichor Foundation, a grassroots football organization focused on the development and empowerment of young women in the capital. “I wanted to photograph them the same way I’d photograph a star athlete,” he explains. “To treat these girls with the same visual respect as someone showing up to set with an entourage.”

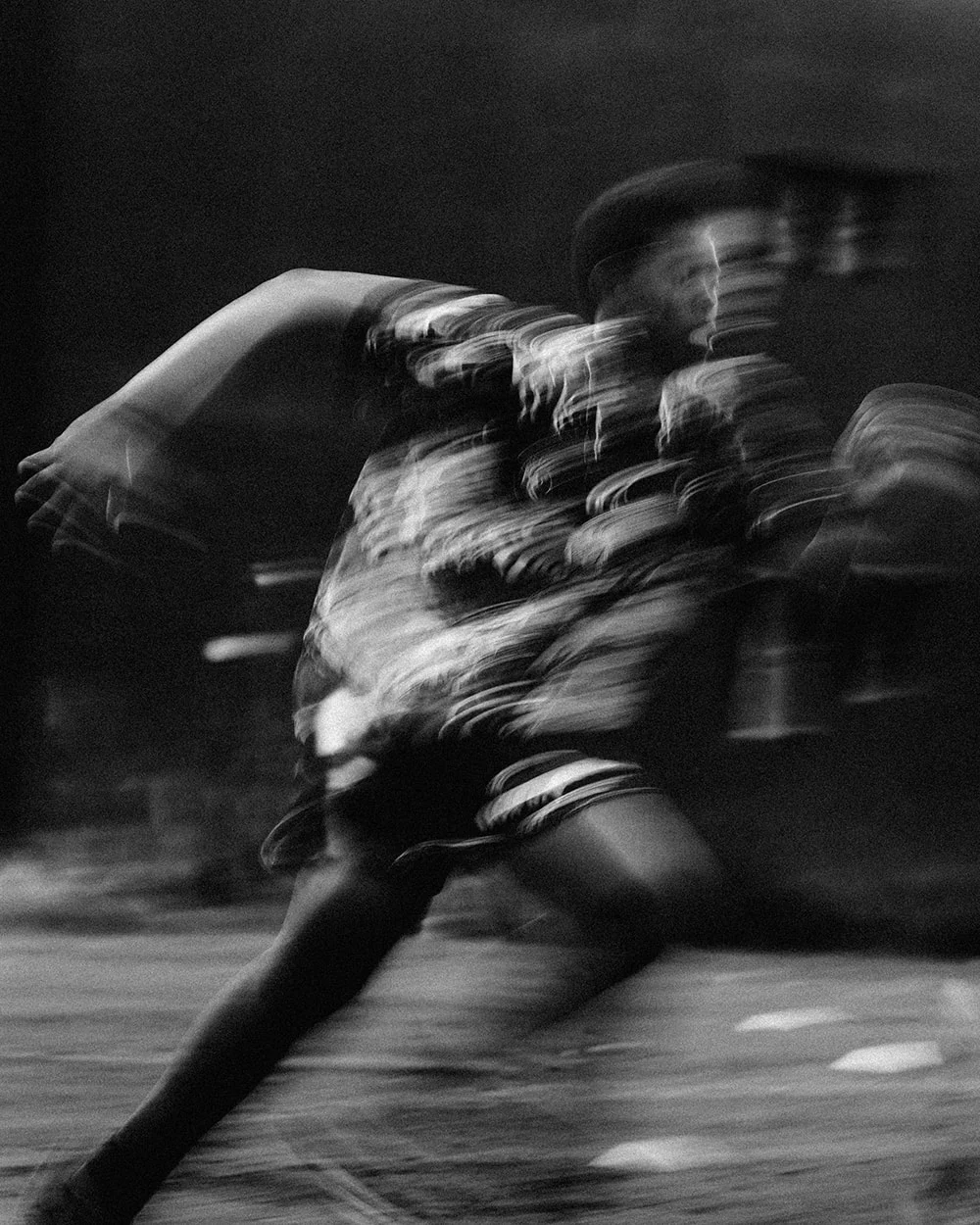

In practice, that meant making conscious choices about how the photos would look, knowing that even aesthetic decisions can often carry heavier meanings. “There are these visual languages we use in photography,” Rasmussen says. “We use a certain look for athletes. A different one for CEOs. And a different one again for people we perceive as having less power—the poor, the displaced, people from the Global South. So I wanted to bring in the visual language we usually reserve for power, and apply it here.”

Some of that was technical—longer lenses, clean light, more formal framing—and some was a more logistical challenge. “We had a local garment worker stitch together pieces of white cloth so we could hang them from the goalposts, rigging up a backdrop on the side of the pitch,” Rasmussen says. “We were out there shooting what could’ve been a fashion campaign. Not to aestheticize them. But to reflect what was already true.”

The result is a kind of gentle confrontation. Photos where the camera doesn’t peer down or steal candid moments from the shadows, but meets the subject on their terms. What grew from an opportunity to photograph Petrichor’s new jersey became so much more. The still portraits are poised and luminous. The action shots, by contrast, embrace streaks of motion blur that feel organic and dynamic: the bodies never frozen, never passive. The pictures pulse with energy. They remind you these girls aren’t just symbols—they’re athletes. “I wasn’t trying to force dignity into the frame,” Rasmussen says. “They already had that. My job was to just show it, and not get in the way.”

Petrichor’s name comes from the smell of rain on dry earth, a signal of renewal. The foundation’s co-founder, Paul, who grew up with Rasmussen at an international school in the Philippines, says it felt right for what they were trying to build. “At first, we weren’t trying to make a big statement,” he says. “No website. No fanfare. We just worked with local clubs, helped them start girls’ teams, coached their coaches, ran training sessions for kids without shoes. Quiet stuff. But the moment we created an outlet for girls to play, you realized: There’s this huge demand. We really found a need that wasn’t being met.”

But Paul, like Rasmussen, is conscious of how easily this work could be misread. “There’s a real risk of the White Saviour Complex narratives here,” he says. “We talk about it a lot. You can’t lead with ego.” From the start, they handed over decision-making to local staff and shifted into support roles. That humility is part of why Petrichor now stands as one of the largest girls’ football initiatives in West Africa.

The girls who come through the programme are given not just structure and support, but a pathway. Some move into Petrichor’s elite team, playing in the country’s second division. A few are now on national youth squads. One, Debbie, just 16, recently signed to a first-division club. Paul remembers her from the very beginning. “That one meant a lot,” he says. “We’d been documenting her story for years. We knew she was special.”

But the work isn’t easy. Players train on uneven pitches. Some come to practice hungry. Many juggle household responsibilities, social pressure, and economic hardship all before stepping onto the pitch. “You don’t just give them a ball and a shirt,” Paul says. “You’ve got to think about what else they’re carrying. What the families are giving up to let them be here. That’s where trust comes in. We build it. We earn it.”

Sometimes that means visiting parents in person to explain why their daughter missed chores to attend a training session. Sometimes it means quietly ignoring rumors that the club is secretly rich, just because a few girls got new boots.

That trust extends beyond football. Petrichor’s goal is sustainability—not just for the club, but for its players, its community, and the people behind the camera. When Rasmussen came in to shoot, he knew he didn’t want to work alone. Local photographers and creatives were invited to assist, shadow, and collaborate. “You’re not just there to take,” Rasmussen says. “You’ve got to make sure what you leave behind has value, too.”

On the project, a local stylist named Criminale brought cultural context to the visual identity, helping tie the new jerseys into a wider story. “He knew how the girls wore their kits. What mattered. What didn’t. That was a huge part of making the images feel authentic,” Rasmussen says. “These projects have to be collaborative. Otherwise, you’re just making something beautiful that disappears the minute you leave.” One of the local photographers on the project, Steve, now helps lead local shoots himself, often using kit Rasmussen had left behind as a thank you.

As one Petrichor player, Yolande, says in the book’s introduction: “We step onto the pitch in a world that tells us we don’t belong…” Whether they end up in a national team or back at home, all the players have a renewed sense of purpose. It is a story, Rasmussen says, perfectly suited to the empathetic medium of photography, even in an era of all-dominant video. “You don’t need movement or sound to show power,” he tells me. “To me, my work is about translation. Finding a language that people already understand and using it to tell a story they might otherwise overlook. If you do it right, a photograph holds someone’s attention. It lets them stay there.”

Creativity should be captured, and for a photographer, having the right equipment can be a crucial ingredient in doing so, allowing them to express themselves fully and do their subjects justice. With a dynamic pricing engine and a circular business model, MPB makes camera gear easily accessible so creatives of all kinds can share their stories. As two platforms that pride ourselves on enabling creativity to flourish the world over, this year, we’re curating some of our photography stories in partnership with MPB, the picture-perfect camera platform.