For some people with disabilities, bed can be a haven of comfort and joy, while for others it’s associated with pain and sickness. “Bed Zine” is the independent publication that invites those with disabilities to explore, through art and writing, the complicated and varied relationships they have with their beds. Writer Madeleine Morley meets the zine’s founder Tash King, and hears how it aims to represent the widest range of feelings from people with the widest range of disabilities from as many places as possible.

I’m writing this article in bed.

I write most of my stories in bed because I have a few interrelated chronic illnesses that make it uncomfortable for me to sit up for long periods of time. Before I even knew I was ill, my desk was my duvet: You’ll often find me with my laptop balanced on a stack of cushions, getting the charger cable entangled with the wire of my fuzzy heating pad. As Lena Dunham has written about her own experience with chronic illness, “I am cozy to survive.” This too is my motto.

When I speak with Tash King, the founder of “Bed Zine,” I’m also in bed. “I’m actually more of a couch girl myself,” she says on the phone from her apartment in Vancouver. We’re talking about how “bed” means so many different things to different people with disabilities; for me personally, I spend most of my day trying to get back into my bed as I love to be here, but for Tash, “I kind of resent my bed because it’s a place where I toss and turn for hours and where I deal with a lot of nerve pain.”

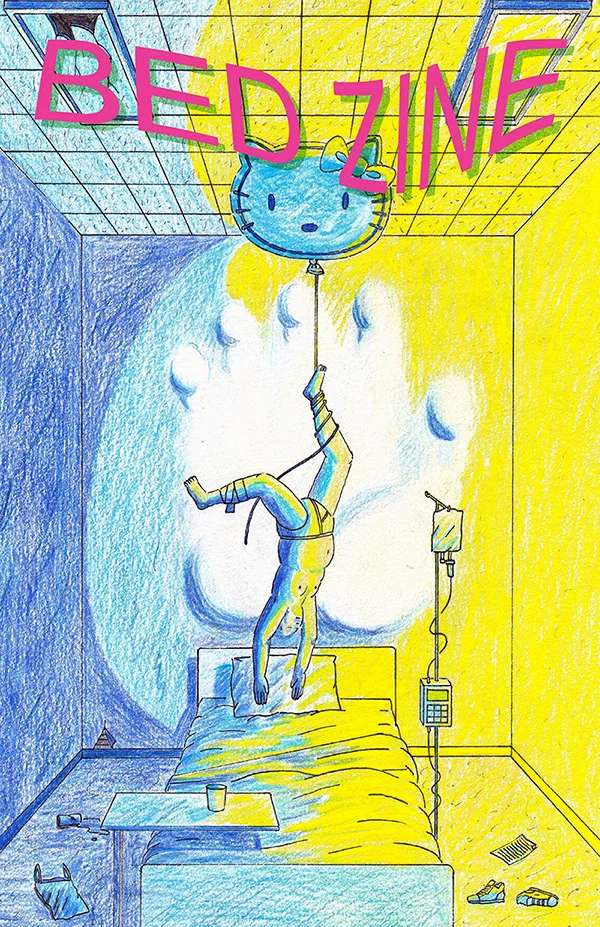

In 2021, Tash launched “Bed Zine” as a space where people with disabilities can explore their complicated and deeply subjective relationships to bed through art and writing. “Since I became disabled, I had struggled to find the disability community that resonated with me,” says Tash, “‘Bed Zine’ helped me grow and connect with disability arts communities I can relate to.”

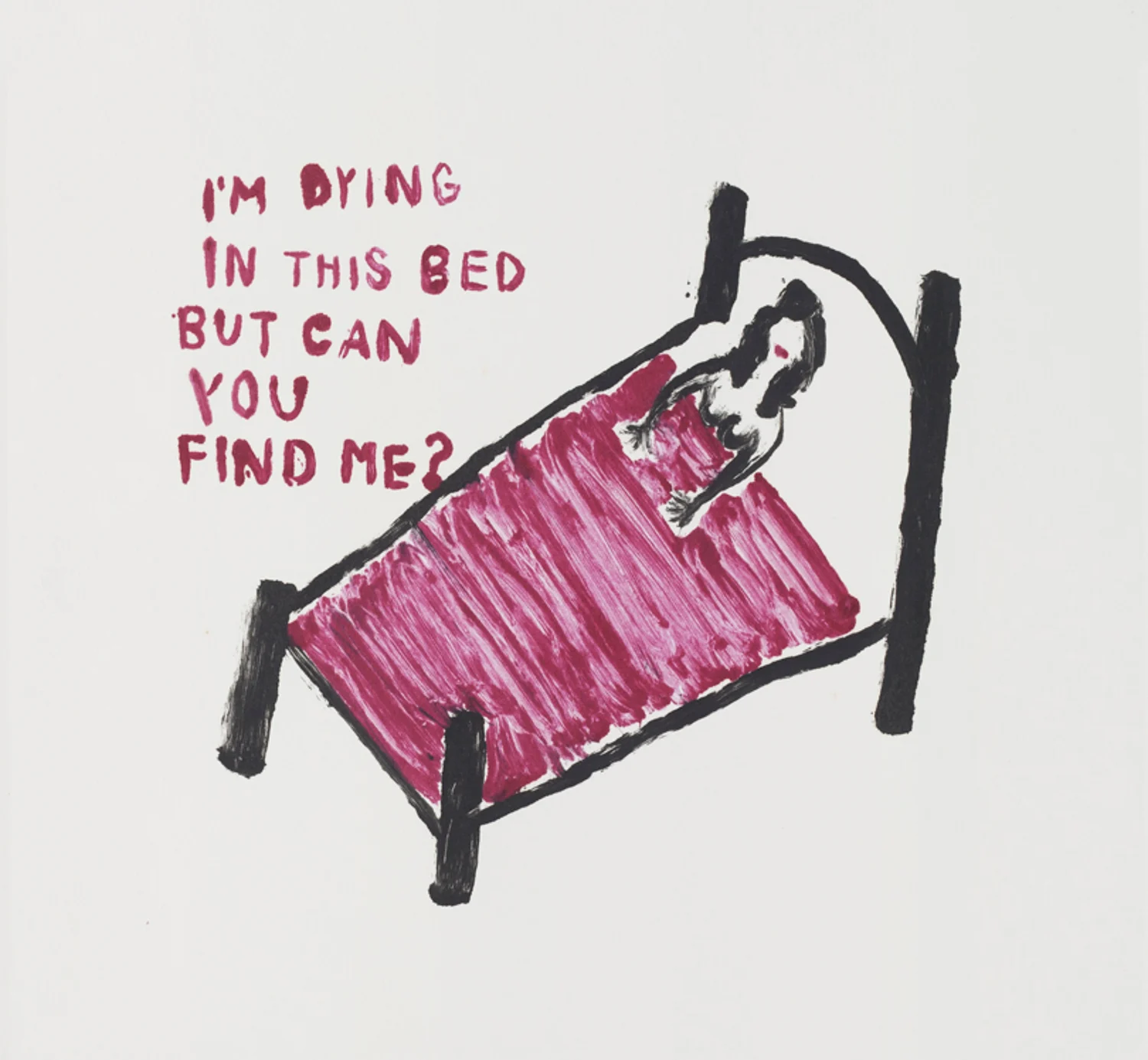

Turning through the spiral bound pages of the second issue — which opens with ease so that people with disabilities that affect their hands can better engage with the content — is an expansive experience. Some submissions frame “bed” as a place of frustration, sickness, sadness and pain, and others as a space of comfort, daydreams, creativity, joy and fulfilment. Very quickly, it becomes clear how varied people’s experiences of bed can be — and what complex meaning it has in the lives of people with disabilities.

“As bed is not a hyper specific concept, it appeals to such a wide range of disabled people,” says Tash, “which means there’s a bigger possibility to reach a larger community.” When sifting through submissions for the zine, Tash looks for final artworks that will come together to, hopefully, “represent the widest range of bed thoughts and feelings from the widest range of people with the widest range of disabilities from as many places as possible.”

It’s a beautiful ethos. Many forums and groups for disabilities that one might initially find online are grouped by disability-type (understandably, to discuss the practicalities of living with a certain condition). So “Bed Zine” creates a different kind of community space: One founded on notions of creativity and solidarity, where one object unites many with various conditions, allowing for explorations of both differences and commonalities.

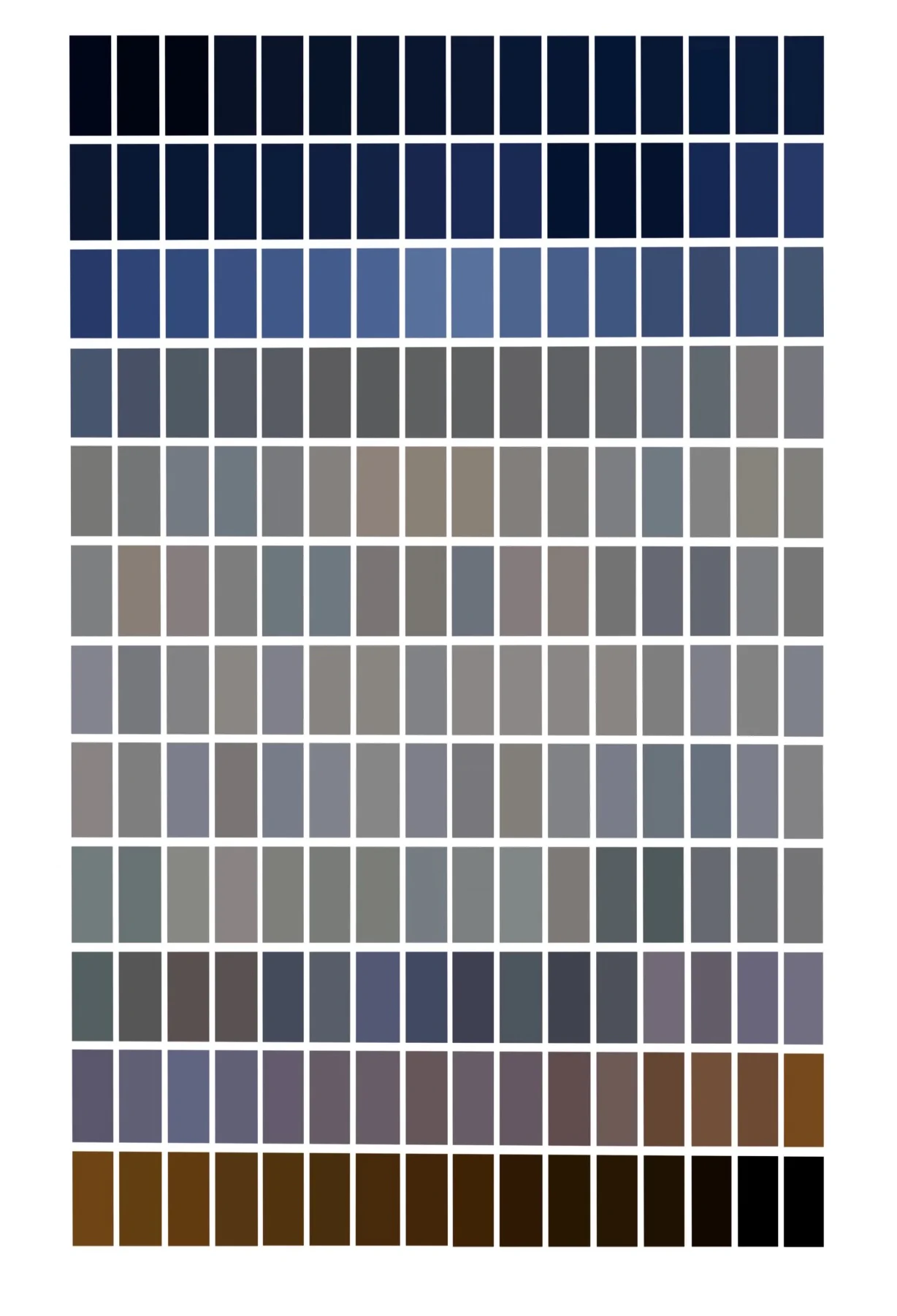

In issue two, artist Rebecca Quinton shares a project about chronic illness — a condition that’s not immediately life-threatening, but which, as she writes, “condemns the sufferer to a permanent stasis between the realms of sickness and health.” Her series, “Shades of White,” features stills of the white walls of her bedroom taken at intervals between dawn and dusk, which appear as shades ranging from dark blue to burnt orange.

The series recalls the strange passage of time experienced during illness. When I personally see it, I feel seen: a mood that I’ve never been able to articulate is vividly expressed on the page. A quilt by artist Amy Claire Mills adorned with the glittering words “Have you tried?,” similarly resonates, a reference to the ill-informed and unsolicited advice those with illnesses are accustomed to hearing.

In issue one, two photographs from artist Hayley Cranberry’s ongoing “Infused” series depicts the artist at home receiving her bi-monthly medical infusion. It’s a striking meditation on the uncanny reality of cold medical instruments making their way into the warmth of home. Works like these offer an intimate glimpse into the inner worlds and lived reality of their makers.

When putting together an issue, Tash first spreads new submissions out on the floor. “Then I spend a couple days sleep deprived, hair in a bun like I’m solving a crime, constantly shifting them around,” she says. “How I put it all together can craft a narrative. I want the work to be featured in a way that gives it the most credit as humanly possible. I feel a responsibility.”

What I personally wonder when speaking to Tash is how she organizes Bed Zine in a way that is mindful of her contributors’ — and her own — conditions. For the chronically ill, energy can often be precious and fleeting — and putting pressure on oneself can spur painful flare-ups. With this in mind, Tash gives herself and others many months to create, with flexible submission dates so that if anything happens, no one is left with having to decide between their health and a deadline.

“I didn’t realize it was possible for myself to engage in projects now that I am disabled without becoming incredibly sick,” says Tash. “It actually feels pretty revolutionary to put the zine together in this way, because I didn’t have any health flares at any time while making it. That makes me realize that it’s possible.” “Bed Zine” isn’t just a forum for conversation then: its very existence and organizational structure resist traditional workflows that can be immensely destructive and inaccessible to people with illnesses.

I tell Tash that I rarely talk about bed. Bed is personal. Bed is comforting, but it’s also something that I hide and feel ashamed of. It can feel hard to tell able-bodied people about how much time I spend here: Are they going to judge me? Offer unsolicited advice? By anchoring our conversation to such a simple object though, talking about the everyday reality of life spent with illness feels possible in a different way. So today, I decide to write this story about writing in bed. “It’s an object that is in all our homes in one way or another,” says Tash, “a space rife with personal meaning.”