Anu Jakobson’s airbrushed artworks capture the chaos of online culture, from the unfiltered randomness of the early internet to today’s infinite scroll. She tells Emma Firth how discovering the airbrush freed her creativity, and how each artwork brings her closer to understanding herself.

Old school reports are almost impossible to throw away. These little time capsules we stuff away in drawers and rediscover every decade or so, in an attempt to bridge the gap between who we were then, who we hoped we’d become and the many different versions of us we ultimately became. Anu Jakobson recently stumbled upon one of hers, or rather one of the first documented manifestations scribbled on an ancient kindergarten development sheet. It read simply and sincerely: I’m five and I want to be an artist.

Despite her obvious desire from a young age, the Estonian artist found she lacked the tools to fully express herself, a visual language to call her own. “Everything changed two years ago when I bought an airbrush,” Jakobson tells me, currently based in Tallinn and studying fine arts at the Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA). “Since then, it’s felt like everything that had built up inside me finally had a surface. I didn’t need a mentor—I just needed permission, from myself, to ignore the weight of tradition and follow whatever felt urgent or alive.” She had no idea how to use it and was “terrible” at first, which was in many ways part of its seduction, that it gave her a sense of freedom to fail.

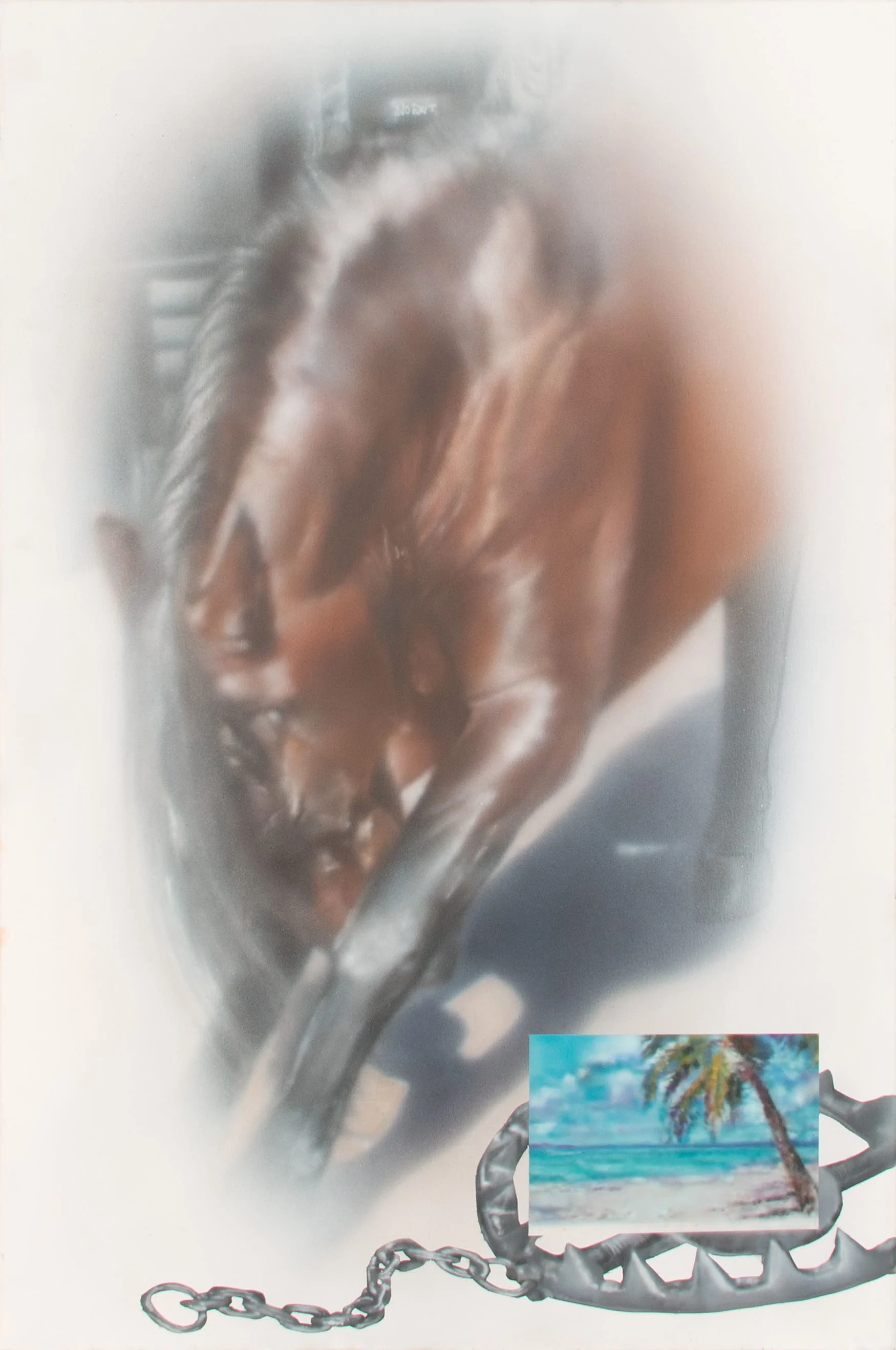

“It showed me I didn’t have to be good to create,” she explains. The airbrush allowed her to experiment in a space that rewards a level of uncertainty, fragments, the contrasts of rough edges and softness. “I could just make things, it let me work without pressure or precision.”

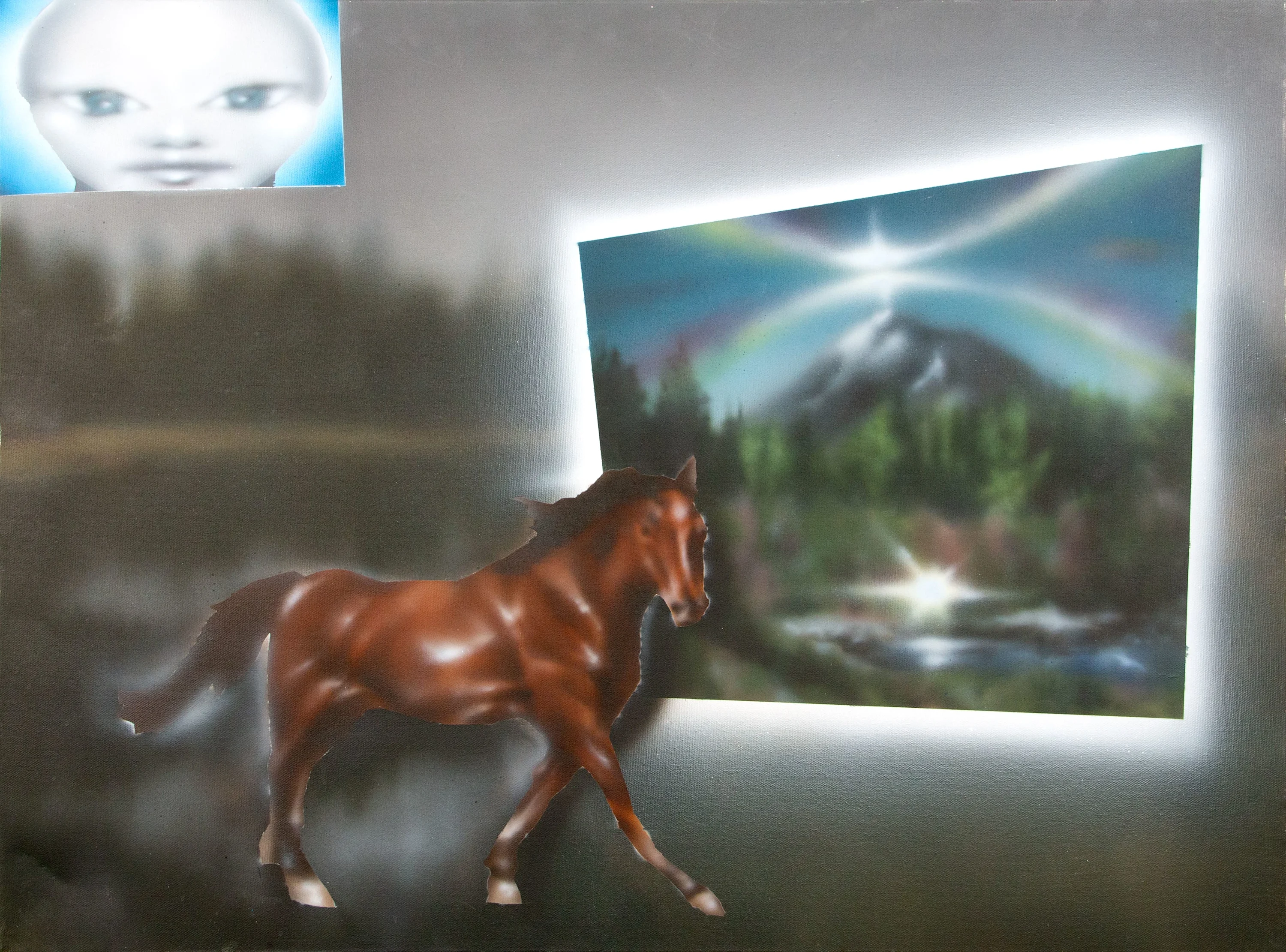

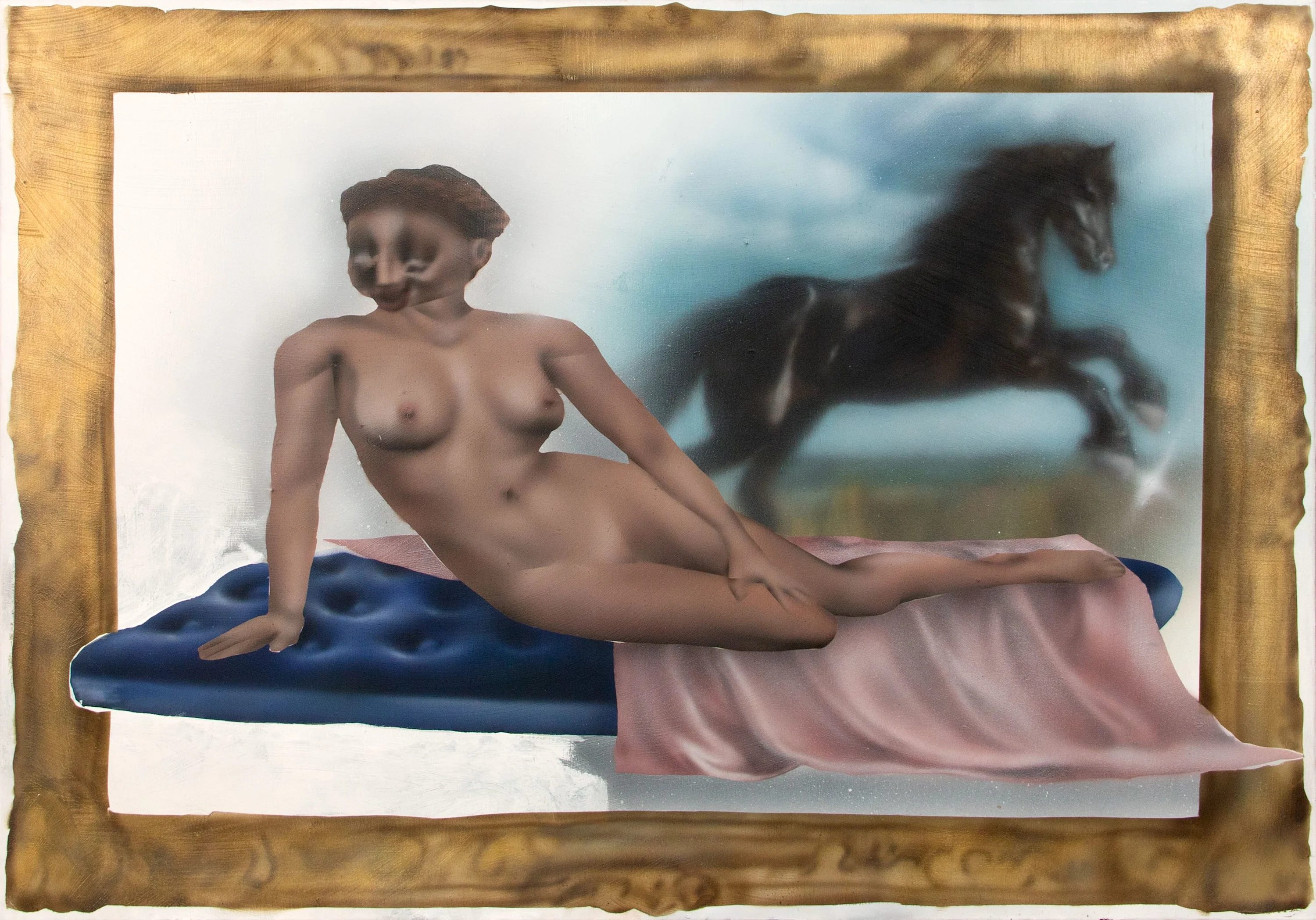

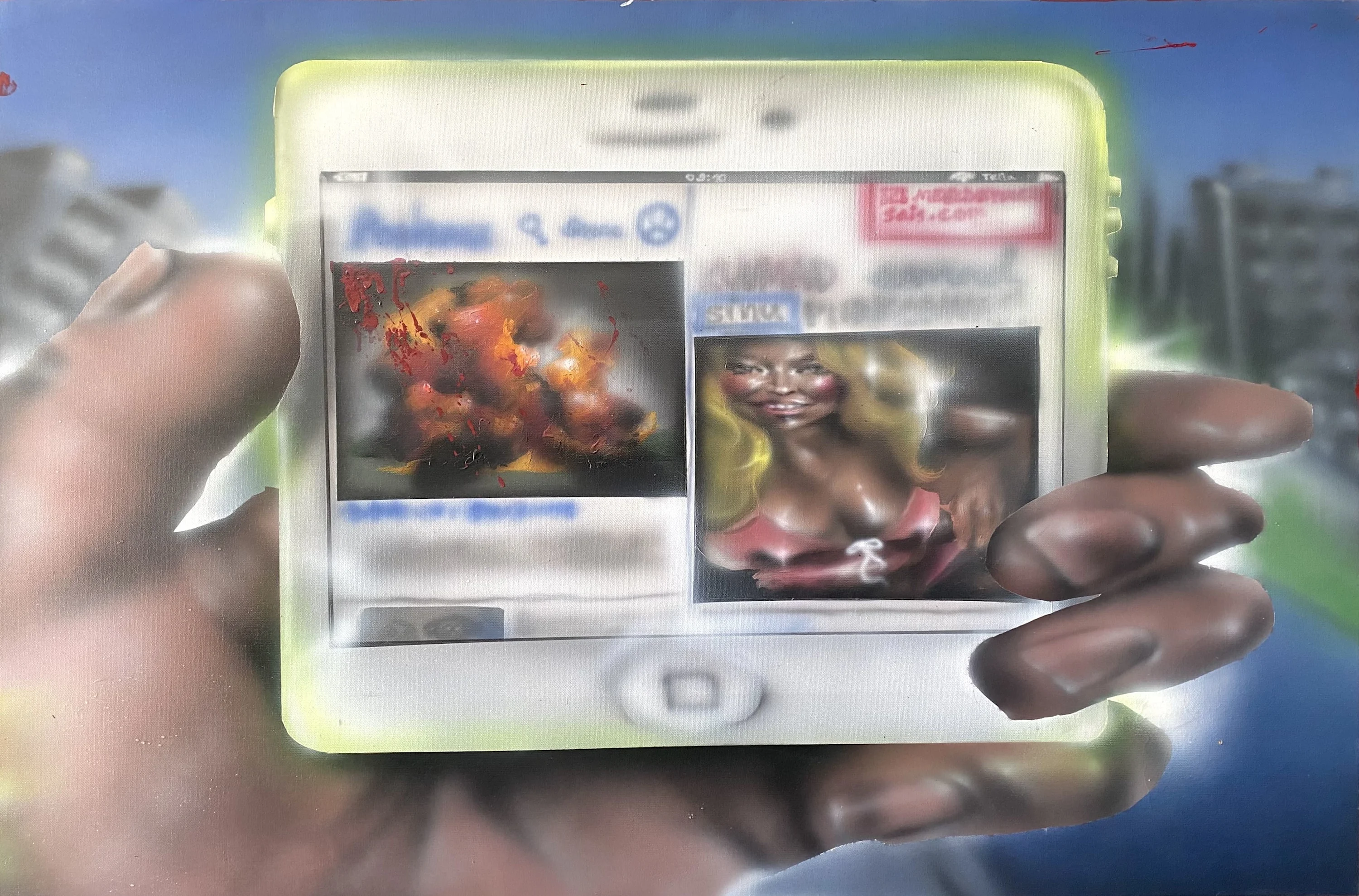

Her muse? Online culture. The good, the bad, the weird and wonderfully absurd. There’s a heavy stroke of nostalgia that runs through her work, capturing the rawness and randomness of the early internet. Unfinished and blurred scenes, cute cat content, flip phones, GIFs, low res, bad crops, “Live, Laugh, Love.” Through her paintings, she explores what she describes as a “digital spirituality.”

I’m not trying to imitate a digital image; I’m responding to what it feels like to exist within one.

“Digital culture has become a collective visual consciousness,” she says. “A constantly evolving ecosystem of signs, references and emotional codes that we’re all contributing to, whether we mean to or not. To be an artist, in this context, means both being a reader and rewriter of those codes.” Her process of making can take anywhere from half an hour to two weeks, usually starting with a sourced image, distorting it somehow, before moving onto the canvas (“covering certain areas using tape to create sharp edges that feel artificial or graphic…almost like early Photoshop”).

“The way the paint lands is unpredictable and imperfect, especially when sprayed from a distance,” Jakobson says. “Even though the airbrush is a traditional, physical tool, the way I use it is definitely shaped by digital culture. I’m not trying to imitate a digital image; I’m responding to what it feels like to exist within one.”

“Leap of faith” and “galaxy cat gif” (“I <3 cats,” she writes via email), are both comments on the experience of living inside an endless visual archive, and how we process that incessant flood of images, whether silly or serious. Where one minute you’re laughing at a stranger’s cat who happens to have millions of followers, doing something totally inane, immediately sharing it with your friend. Next thing, you’re fed the most disturbing clip you somehow can’t switch off. And so, the loop continues, oscillating between so cute, so cool, so sad.

If ever struggling for inspiration, it is more often vintage corners of the internet, “2010 Tumblr” for instance, that Jakobson will turn to for discovery. “There’s something more genuine and unexpected there, less curated and not optimized for performance,” she says. “I also look to books about new media, digital culture and visual language. I’m drawn to places where the content isn’t trying to sell itself to me, where I have to dig a bit.”

Jakobson also finds joy in offline pursuits in her spare time, many of which often feed into her artistic practice. Her current great escape is a dialogue with herself, thanks largely to a hyper fixation on Carl Jung’s philosophy on the shadow self.

Confronting who she is and what she sees when she dreams—in stark opposition to her waking life—has proved unexpectedly comforting. Jung’s writing has helped her view these figures with her eyes wide shut as far from alien, illogical or disconnected, but rather “as reflections of my own inner world,” she says, “as traits that are either repressed or ignored, making it easier to understand certain patterns in myself. For me, making art is the closest I’ve come to knowing myself. Every painting, even the ones that seem vague, reveals something to me. Not always clearly, and not always comfortably.”

As someone who regularly, sometimes even happily, can waste entire evenings scrolling through Instagram consuming otters, swans or turtles in warm and loving embraces, Jakobson’s piece “8 hours of screen time” strikes a chord with me. Somewhat ironically, she admits she’s turned her time monitoring off. As she says, “ignorance is bliss.”