The Kitchen Gods are spirits worshipped in many Vietnamese households that watch over the home and the family’s well-being. Through still lifes and staged portraits of herself and friends, photographer Anh Nguyen playfully explores the imaginative landscape of this ancient myth. She tells Marigold Warner how the project allowed her to better understand her heritage, from how it can be kept alive after leaving home to the ways younger generations are re-interpreting age-old traditions in the present day.

“The Kitchen God” was recently selected as a winner of Open Walls Arles, an award held by WePresent in partnership with the British Journal of Photography.

Every year in the lead-up to Lunar New Year, Anh Nguyen’s family prepares a platter of delicacies. Sweet treats, tropical fruits, meats, spring rolls, a whole chicken and cans of beer—all delicately plated up with bright pink lotus flowers and incense sticks. This elaborate display is an annual offering to the elusive Kitchen God, whose porcelain figure sits on the altar year-round, overseeing the family’s well-being and household affairs. Growing up in Saigon, Nguyen rarely questioned this tradition. “It’s something that was always there, but I didn’t quite realize its significance until I stepped away,” says the photographer, who is now based in New York. “Vietnamese people really believe that these gods are responsible for the happiness and safety of the family, and that’s why the ‘sending off the kitchen god day’ really matters.”

It’s something that was always there, but I didn’t quite realize its significance until I stepped away.

The legend goes like this. There once was a married couple called Trọng Cao and Thị Nhi, but after a tempestuous quarrel he cast her out. Thị Nhi was heartbroken, but she eventually remarried a hunter called Phạm Lang. Years later, Trọng Cao was filled with regret. He set off on a journey to find his former wife, but quickly ran out of food and resorted to begging. By chance, he knocked on her door. Pitying her old lover, Thị Nhi fed him, but soon after her new husband returned. Thị Nhi hastily hid her ex-husband behind a haystack. To her shock, Phạm Lang unknowingly set the haystack alight and out of despair, Thị Nhi threw herself into the fire. Shocked and confused, Phạm Lang jumped in after her. Up in the heavens, the Jade Emperor was touched by their fate, and united their spirits into one: the Kitchen God, guardian of the household.

Nguyen’s photography series explores the imaginative landscape of this myth, and the role of the Kitchen God as an all-seeing entity. “As I was photographing my friends in their homes in New York, I felt like I was the Kitchen God in their home, observing them,” she says. “The narrative of Vietnamese immigrants in the US is very much tied to the end of the war. Now, my generation gets the choice to live here. That adds another layer of guilt… and why I wanted to explore the feeling of being observed—like you’re under scrutiny.”

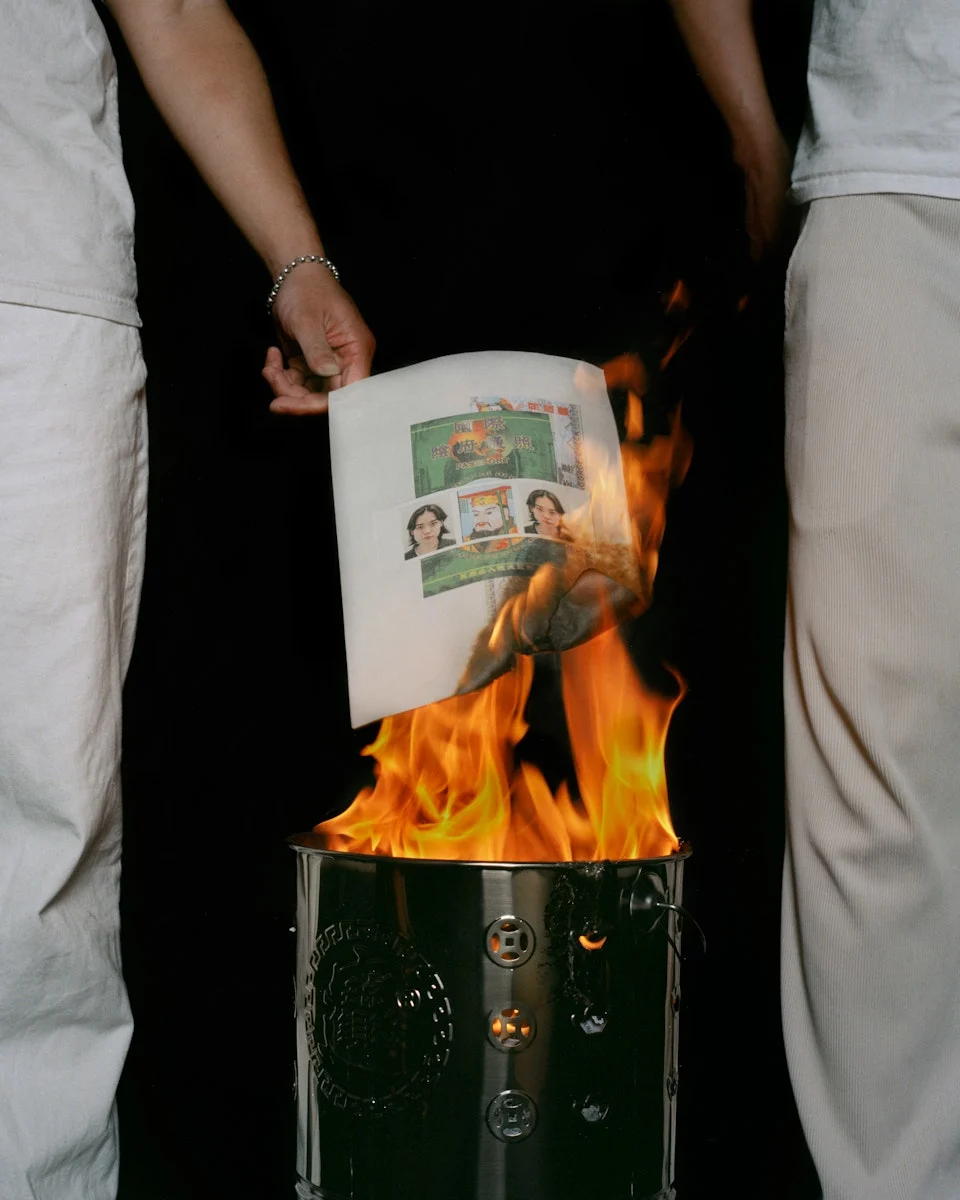

Nguyen’s images are playful and performative, a collection of symbolic still lifes and staged portraits of herself and friends. We see sacks of banh tet—sticky rice cakes—hung out to dry with a plain-white-tee on a Brooklyn rooftop. Elsewhere, friends play bầu cua cá, a popular folk betting game, except they’re using Venmo to settle up. In the glossy world of Nguyen’s images, tradition becomes a tool to explore how young Vietnamese are re-interpreting their culture in the present day, and how stories are passed down and adapted across generations and continents. “There’s no correct form of it,” says Nguyen, “that’s another interesting thing for me—how mythology gets retold”.

That’s another interesting thing for me—how mythology gets retold.

Anh’s unique perspective is shaped by her dual upbringing. She attended an international school in Saigon, where she grew up speaking both English and Vietnamese. She moved to New York around four years ago, after studying photojournalism in Boston. “I’m part of a generation that grew up globalized. The things we were consuming were part of a shared Internet language… A lot of that has influenced my visual world, and my view of culture,” she says. After college, she completed a one-year program at the International Center of Photography in New York, where she started The Kitchen God Series. “This project changed my mind about photography. I used to see it as a necessity—not as an art, but as information,” says Nguyen. “Photographs can be playful, and not necessarily just a form of truth.”

In one image, for example, Nguyen constructs an offering for the Kitchen God. She thought, “If my parents were making me an offering table because they missed me, what would they put on it?” Much to her family’s disappointment, Anh is vegetarian, so her offering table presents a rubbery vegan chicken and imitation lobster, shot in her trademark style—well-lit and clean, but with a touch of subversion. Other images share similar undercurrents, like a shot of her friends gathering around a table to toast the Lunar New Year. The occasion is meant to be joyful, but “it’s not particularly a welcoming feeling,” Nguyen remarks. Expressions are deadpan, gazes direct. “In a lot of the photos, I’m thinking about the food. And that reflects my relationship with meat too. I think about it so much—I miss it so much—but it’s so hard to find anything that’s vegetarian in Vietnam.”

When you move away from home, the presence of your loved ones or what you left behind becomes almost mythological.

All of this charts Nguyen’s process of understanding her heritage, especially now that she lives abroad. “It made me realize that all traditions are interpretive,” she says. And does she still feel as though she is being watched? By an all-seeing, all-knowing Kitchen God? “To me, the presence of the kitchen gods in this series is playful,” she reflects. “But maybe it more so represents how, when you move away from home, the presence of your loved ones or whatever you left behind becomes almost mythological. Whether it’s my parents, ancestors, or just the general idea of the “homeland”—I feel like my actions are always being watched by them from afar.”