Amy Hussein’s ongoing series of paintings—depicting hybrid beings with female-identifying and non-binary Arab faces and animal bodies exploring Caribbean landscapes—is primarily a love letter to her Lebanese-Dominican identity. She uses old family photos to inspire the characters’ faces, exploring the spiritual connotations attached to certain animals and investigating mythical creatures of the ancient world in the process. Hussein tells Alix-Rose Cowie how the project not only brought her closer to her ancestors and to a better understanding of her identity, but also allowed her to celebrate history’s strong, multifaceted women.

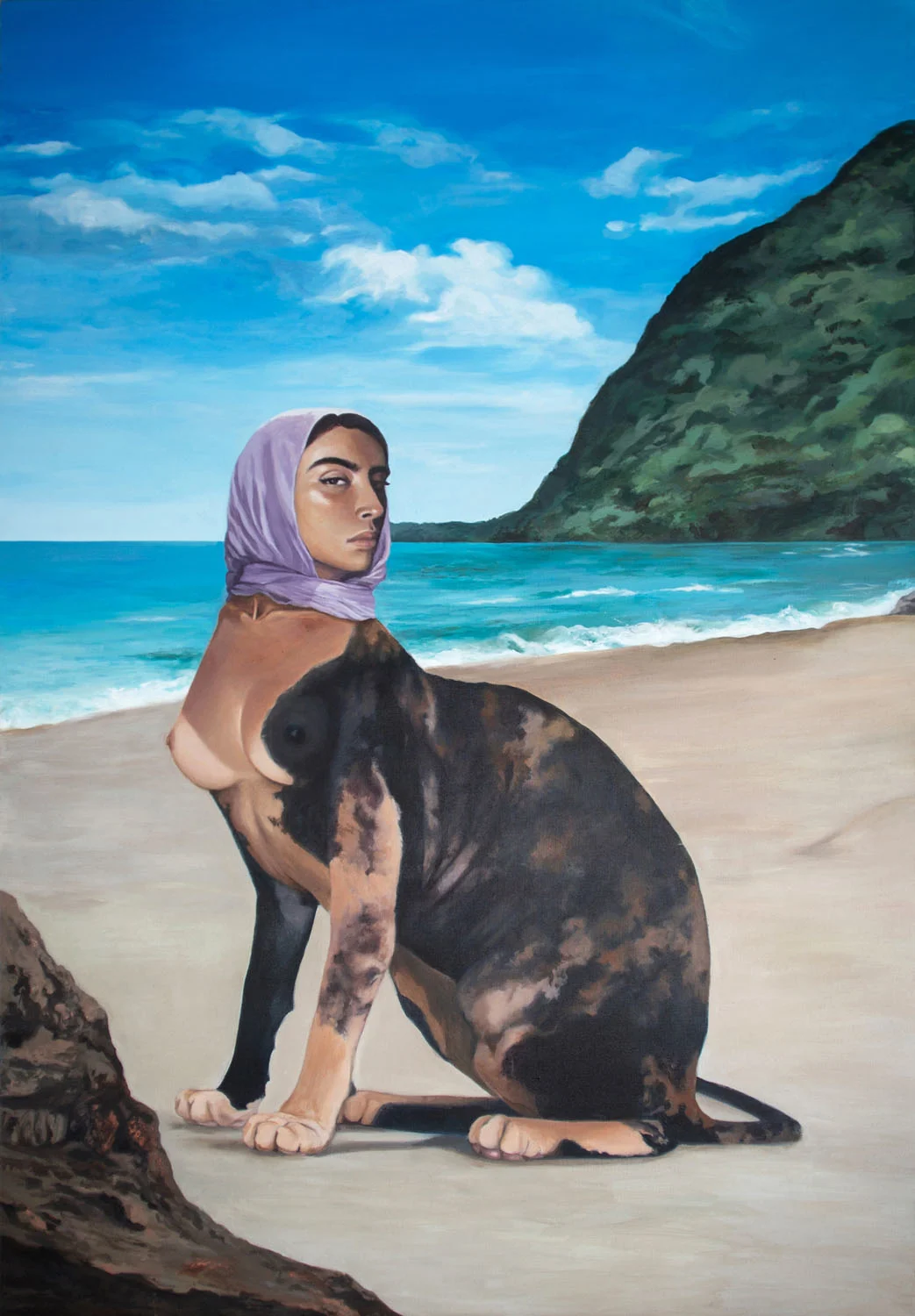

In multi-disciplinary artist Amy Hussein’s painting “Alwadi,” a creature with the body of a calico sphynx cat and the breasts and head of a woman in a lavender headscarf sits on a picturesque beach lapped by turquoise waters. It was one of the first paintings in Hussein’s ongoing series through which she explores her Lebanese-Dominican identity. Inhabiting Dominican landscapes, her imagined hybrid beings have female-identifying and non-binary Arab faces to represent her mixed heritage. “I wanted to find myself and understand who I am,” she says. Her sphynx cat Margarita (Spanish for Daisy) was the muse for this painting: “Sphynx cats in general interest me, not just because of their aesthetics but because of their origin and how they are perceived,” she says. Resembling sphinx statues and cat statuettes, they’re often mistaken as ancient Egyptian cats, but in reality are traced back to Toronto circa 1966. “I can relate to this through my own experiences of belonging.”

Hussein’s dad was born into a Muslim family in Lebanon and immigrated to the Caribbean during the Lebanese Civil War to start a new life. Not easily accepted due to racial politics, he tried to separate himself from his culture. “We were never taught Arabic growing up,” Hussein says. “He tried to protect us through assimilation, which I understand but I'm very torn about as it made communicating with my family in Lebanon difficult.” Though close to her mother’s Dominican family, there were always holes in her knowledge of her father’s side.

As an adult, she took it upon herself to collect all the family photos and oral stories including her father's photos from Lebanon, and began to scan, archive, and organize them. “We’d have lengthy conversations where I’d ask him to share his experiences, to better understand him, his decisions, and our father-daughter relationship,” she recalls. These paintings came from that process of investigation, which included uncovering other stories of Arab migration to the Caribbean helping to shape a broader understanding of her personal story. The artworks are a love letter to that meeting of cultures. There's no way that I can speak for the Lebanese people. There's no way that I can speak for Dominican people. But I live in this liminal space which is a world I can speak from.”

Hussein became fascinated with chimerical creatures prevalent in mythology from across the ancient world, from Persia to India. In stories, the Greek or Levantine sphinx—with the face and breasts of a woman, the body of a lion and the wings of a bird—would present those who encountered her with a riddle. If they answered wrong, she would devour them. These beasts could be interpreted as powerful women whose agency or existence threatened the Gods. “In contemporary times women are still being labeled monstrous if they refuse to conform,” Hussein says. “I’ve always struggled with classical notions of femininity and beauty equated with being proper, delicate or feminine. I wanted to vindicate women's rights to be monstrous.”

Hussein’s style has developed according to her interests. When she first started drawing as a child she loved watching “Sailor Moon” and “My Little Pony.” The pastel color scheme of a friend’s Trapper Keeper school binder with a horse on the cover has directly influenced the hues of some of her paintings. She loves the kitsch or romantic imagery of old puzzles like a sunset scene of horses running on a beach. “I like working with generic imagery that people can easily recognize,” she says. “I prefer to attract the viewer with safe aesthetics and then introduce difficult narratives for them to contend with.”

The landscapes she chooses are real places in the Dominican Republic but intentionally rendered in the saturated colors of a travel brochure and the pristine quality of real estate photographs, as she feels “these natural places are often threatened by real estate speculation.” A little glitter mixed with her acrylic paint sometimes does the trick too.

The faces in Hussein’s paintings are fictional but based on family members, women who inspire her or self portraits. Her painting “Salinas” pictures Salado del Muerto, a salt mine close to where her mother was born, founded by Nicolás de Ovando during the Spanish Colonization. The horses struggling in the pink waters of the lake represent her parents and the hardships they went through to give their children a better life than they had. The shiny black horse on land is herself, painted to acknowledge her privilege but also more generally to recognize the place's history of exploitation of racialized bodies.

Hussein closely considers the spiritual and cultural meanings or connotations of the animals she pairs people with, and the poses they’re in. “In the Dominican Republic the goat has been associated with the tyrant Trujillo,” she says. “During his dictatorship some women dressed as men to avoid being exploited.” In a painting of hers, a woman-goat attempts to blend in with real goats in an attempt to assimilate for her survival.

Although predators have been featured in Hussein’s works, some show more domesticated animals. “There can be a feral spirit in soft animals too,” she says. “Cats have sharp claws and teeth, which they choose to use or not.” She goes for “a mixture of dangerousness” in the animals she depicts. “I don't want to always equate women with dangerous animals,” she says. “There's power in softness too.”